The Dawn of Commercial Thermoforming

Previous Article Next Article

By Stanley R. Rosen

The Dawn of Commercial Thermoforming

Previous Article Next Article

By Stanley R. Rosen

The Dawn of Commercial Thermoforming

Previous Article Next Article

By Stanley R. Rosen

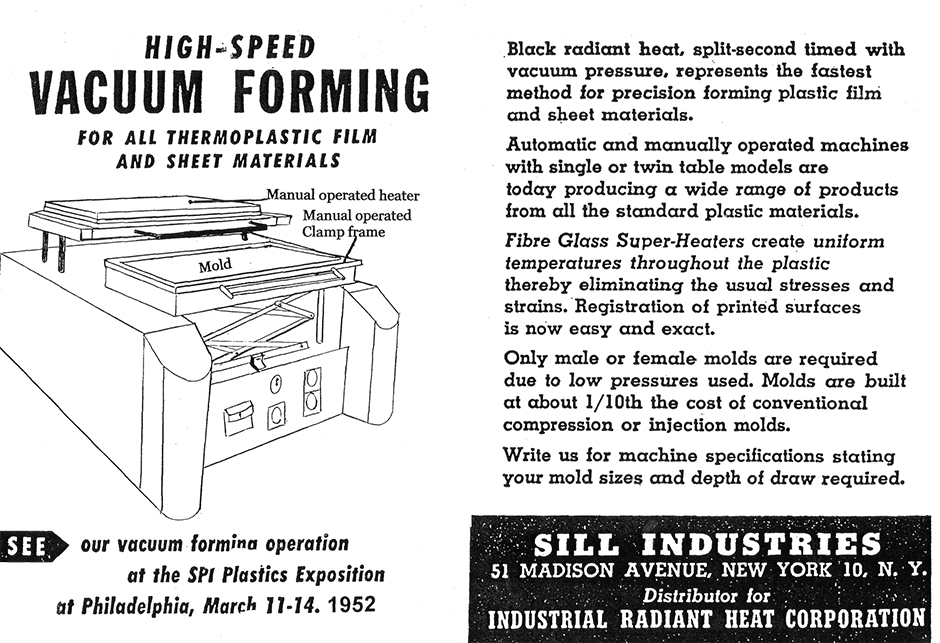

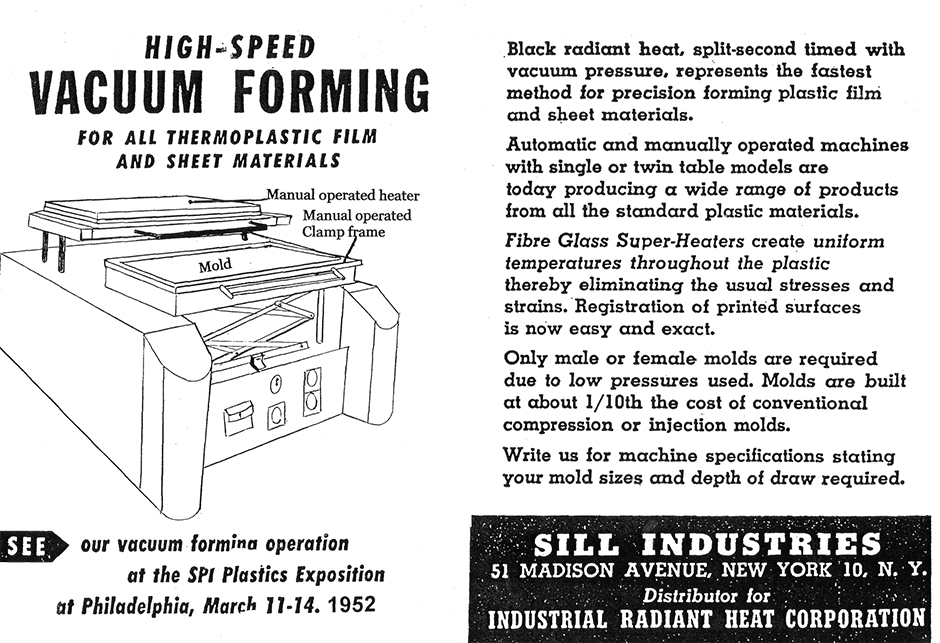

Figure 1: Industrial Radiant Heat Corp. of New Jersey introduced this thermoforming machine — the first such model to be offered widely for sale — at the 1952 NPE trade fair in Philadelphia, where it attracted substantial attendee interest and spurred a number of competitors to enter the market.

Figure 1: Industrial Radiant Heat Corp. of New Jersey introduced this thermoforming machine — the first such model to be offered widely for sale — at the 1952 NPE trade fair in Philadelphia, where it attracted substantial attendee interest and spurred a number of competitors to enter the market.

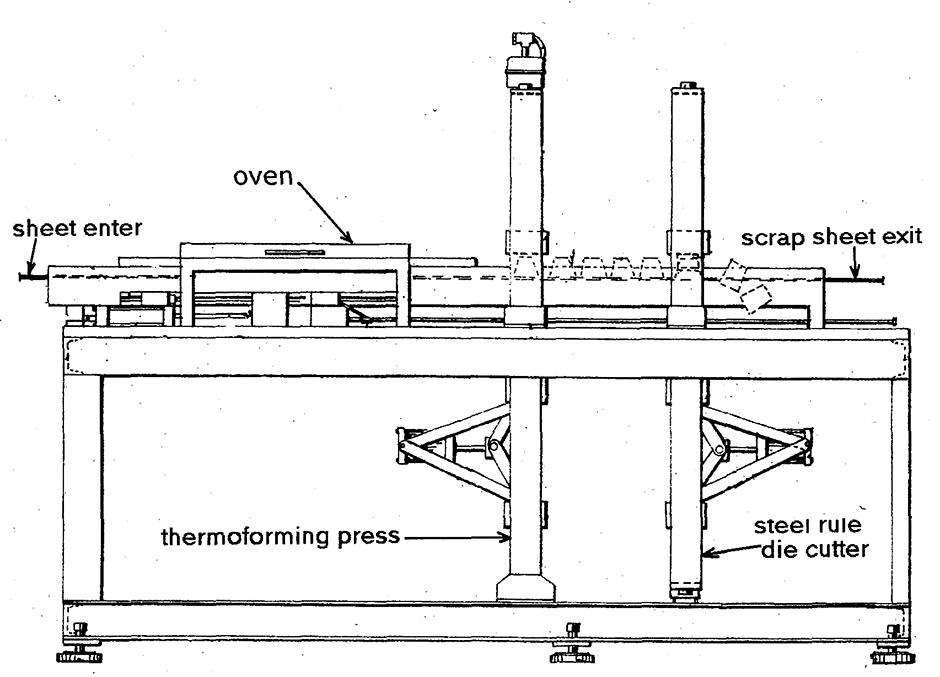

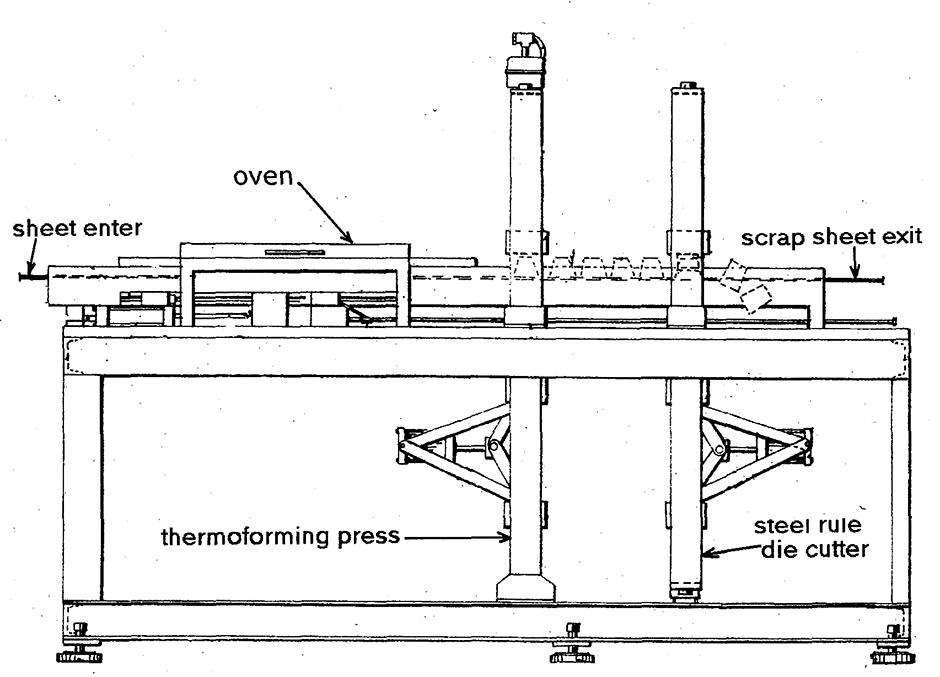

Figure 2. In 1965 Brown Machine developed this inexpensive, roll-fed pressure former, which ushered in the modern thermoforming era. This machine, with its in-line steel rule die press, produced thermoformed parts that emerged from the machine trimmed and ready to be shipped.

Figure 2. In 1965 Brown Machine developed this inexpensive, roll-fed pressure former, which ushered in the modern thermoforming era. This machine, with its in-line steel rule die press, produced thermoformed parts that emerged from the machine trimmed and ready to be shipped.

Thermoforming is the process of heating a thermoplastic sheet and using vacuum or compressed air to form the sheet to a mold and later trim to size each individual cavity. Several firms during the 1930s and 1940s designed and built proprietary machines that were used to thermoform small quantities of plastics products. None of this equipment was ever sold to processors in the plastics industry.

The U.S. Army Relief Map Division, whose chief was E. Bowman (Bow) Stratton, developed a practical method of vacuum forming 3-D topographic maps during World War II. When the war ended, the army vacuum former was upgraded and the Industrial Radiant Heat Corp. of N.J. was created to promote and sell this equipment.

The firm first demonstrated its machine at the National Plastics Exhibition in 1952 in Philadelphia (Fig. 1). Modern Plastics magazine in May 1952 noted: “This booth attracted more continuous attention than any other exhibit.” The process appealed to many attendees due to the low cost of the equipment and tooling when compared to injection molding.

Within a very short time, machinery competition arose: J.E. Kostur - Comet Corp. (Chicago), David Zelnick - Atlas Corp., now the Zed Corp. (Rochester, N.Y.), and Bow Stratton’s Auto-Vac Corp. (Bridgeport, Conn.) all built well-engineered vacuum formers. These machines used cut sheets and required a relatively long heating cycle as the oven contained only top heating elements. The formed shot was trimmed using knife-like steel rule dies in presses adapted from the printing or shoe-making industries.

Every new thermoformed component required its own mold and this expense was amortized over the total number of parts purchased. Customers placing initial small orders to market-test this new process needed to minimize the cost of each mold. Molds were built using a model or a wooden pattern to vacuum form individual plastics cavities. Liquid epoxy or plaster was poured into these cavities and cured to create an inexpensive mold. Both cavity materials are poor heat conductors, resulting in a very slow thermoforming cooling cycle.

Inefficient machines and molds when combined with low volume orders tended to restrict new machinery sales and reduce technical innovation during this early period.

In 1954, retail merchandising started to shift from traditional clerk assistance to consumer self-service. This trend introduced a change in product packaging favoring heat-sealed plastic blisters on cards mounted on peg board displays. This package gave thermoforming suppliers a huge new market. Newly designed roll-fed thermoformers and heat-efficient aluminum molds were quickly designed to supply the rapid increase in volume for blister packaging. For the next four to five years, most of the thermoforming technical development aimed to improve existing machine designs.

The industry was not yet ready to pay the cost to solve the problem of trimming parts in-line from a continuous thermoformed web.

In the late 1950s, Dow Chemical, Maryland Cup and an ingenious inventor, Gaylord Brown of Beaverton, Mich., collaborated to mass produce plastic cups and lids. Their endeavor resulted in successfully building a continuous sheet forming and trimming inline system for food and drink containers.

Brown Machine Co.’s thermoformer indexed a continuous sheet through a multi-stage oven into a pressure-forming press, and the web then moved on to a free-standing trim press. The trim press re-indexed the web into a punch and die where individual cavities were trimmed and packed. The older model roll-fed vacuum formers operated at 2-5 cycles/min., compared to the Brown pressure former that operated at 20+ cycles/min. A mold and die for the Brown thermoformer and trim press cost more than a new commercial vacuum former. When producing 100 million lids the tooling cost per unit is negligible, but a 100,000-unit blister order could not support the cost of this efficient machine and its tooling.

Roll-fed thermoforming split into two branches: large, well-capitalized food packaging suppliers, and the smaller custom thermoforming firms that served a wide variety of businesses. Several custom firms purchased Brown thermoformers and bought water-cooled, multipurpose master mold bases that cycled at the intermediate speed of 8-12 shots/min. An in-line guillotine shear was used to cut-off each shot, and then the cavities were manually steel-rule die cut. The Brown thermoformer’s capabilities enabled some tooling to be converted from vacuum to pressure forming, and machine operators became more expert at their jobs using the power of pressure forming.

In 1965, Jack Pregont, president of Prent Corp. in Janesville, Wis., urged Gaylord Brown to build an inexpensive, roll-fed pressure former with an inline steel rule die press (Fig. 2). It was a great success, as it mainly eliminated manual die cutting and soon larger, more sophisticated models followed. Almost all thermoforming machinery companies now build similar machines for the industry.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stanley R. Rosen has spent half a century as a mechanical engineer, designing thermoforming machines. He founded the Mold Systems and Hydrotrim companies in Valley Cottage, N.Y. Those firms specialized in the design and building of thermoform tooling, sophisticated laboratory thermoforming machines, and large hydraulic die cutters. Rosen was elected chairman of the board of the Society of Plastics Engineers’ Thermoforming Division, and has been honored as SPE’s Thermoformer of the Year. He is author of the book “Thermoforming: Improving Process Performance.”

Stanley R. Rosen has spent half a century as a mechanical engineer, designing thermoforming machines. He founded the Mold Systems and Hydrotrim companies in Valley Cottage, N.Y. Those firms specialized in the design and building of thermoform tooling, sophisticated laboratory thermoforming machines, and large hydraulic die cutters. Rosen was elected chairman of the board of the Society of Plastics Engineers’ Thermoforming Division, and has been honored as SPE’s Thermoformer of the Year. He is author of the book “Thermoforming: Improving Process Performance.”