By Robert Grace

By Robert Grace

By Robert Grace

Dresden Optics offers a single style of eyeglass frame, with interchangeable parts. It prides itself on its vast array of colors – some are one-of-a-kind because they choose not to fully purge the injection press between runs.

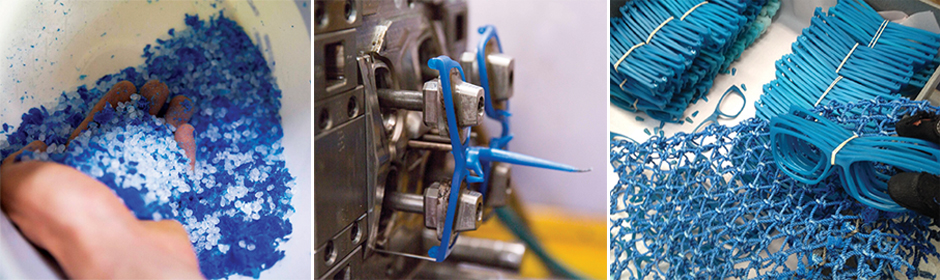

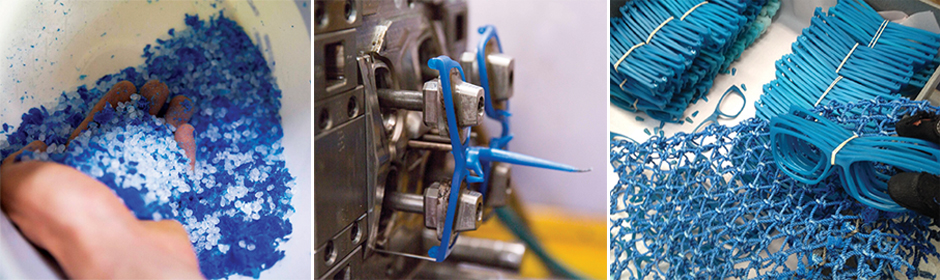

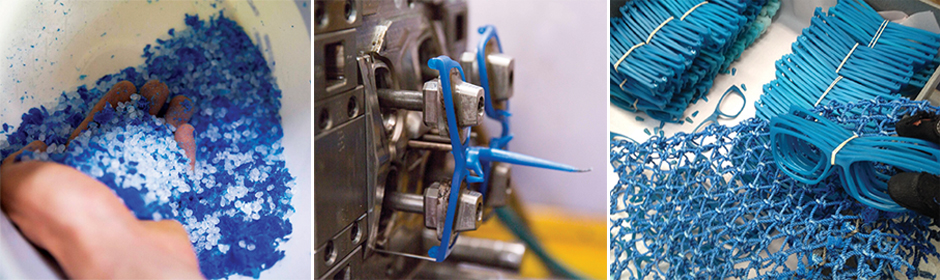

Dresden sources its used plastics from many sources – from LDPE milk bottle lids (above left) and HDPE beer keg caps, to PP takeaway food containers and nylon 6 fishing nets (above right). Sydney-based automotive supplier Astor Industries molds the frames (above middle).

Dresden sources its used plastics from many sources – from LDPE milk bottle lids (above left) and HDPE beer keg caps, to PP takeaway food containers and nylon 6 fishing nets (above right). Sydney-based automotive supplier Astor Industries molds the frames (above middle).

Dresden sources its used plastics from many sources – from LDPE milk bottle lids (above left) and HDPE beer keg caps, to PP takeaway food containers and nylon 6 fishing nets (above right). Sydney-based automotive supplier Astor Industries molds the frames (above middle).

Jack Piper, head of Dresden’s R&D, sorts beer keg caps that the firm plans to recycle into eyeglass components. The firm’s goal is to eventually make all its products from 100% recycled resin.

Jack Piper, head of Dresden’s R&D, sorts beer keg caps that the firm plans to recycle into eyeglass components. The firm’s goal is to eventually make all its products from 100% recycled resin.

Jack Piper and his colleagues at Dresden Optics Pty. Ltd. in Australia want to put a new face on the business of eyeglasses. At the same time, they believe strongly in environmental stewardship and a circular economy. And so they’re doing their modest bit to drive that concept forward – one set of recyclable glasses at a time.

The company’s co-founders – Bruce Jeffreys and Jason McDermott – describe themselves as frustrated glasses-wearers. Because, they note, glasses are annoying. “You lose them, you break them. You scratch them. You forget them. They’re fragile, expensive and hopelessly inconvenient.”

Jeffreys and McDermott decided to do something about it. They conceived the idea for a new type of eyewear company in late 2013 and opened their first shop in July 2015. They were attracted to a craft excellence and to the German approach to both design and manufacturing. “We admire how Germany has maintained its traditions, yet has a hypermodern, progressive edge,” they said. Hence, the adoption of the name Dresden Optics (after the German city of Dresden) for a startup company in the Sydney suburb of Newtown.

The founders’ one rule when first assembling its new team, explained Piper, the firm’s head of research and development, was that no one was allowed to be from the optics industry. Piper – the Canberra-born son of United Nations officials – has lived all over the world, earned a structural engineering degree from the University of Sydney and did his honors research in water storage solutions for drought-stricken villages in the mountains of Nepal.

“Despite having no experience in manufacturing or plastics,” he said recently, “we were determined to do it our ourselves. The more we learnt about various methods of manufacturing, the more we realized how much fun we could have with injection molding. In our ignorance we assumed that once you had a mold you could just throw anything you liked in there so we started mucking around with recycled plastics and bioplastics and realized that though anything might be a bit strong, there was a lot out there that we could get away with.”

The Dresden team’s vision was to create simple yet stylish eyeglasses that were very durable, lightweight, inexpensive and made locally. The injection molded plastic frames – made from Swiss compounder EMS-Grivory’s Grilamid TR90 nylon – are fully recyclable.

Dresden also has been experimenting with making eyeglass frames from recycled waste plastics recovered from the following diverse sources: low-density polyethylene milk bottle lids, high-density polyethylene keg caps, and polypropylene takeaway containers – all from Newtown cafés and brewers; recycled PET (rPET) from a local recycler; and recycled nylon-6 ghost fishing nets from a Byron Bay marine debris collector. They’ve also explored using a castor-oil-based bioplastic from Evonik.

The company trusts that when consumers who buy a pair of their low-cost, recycled-plastic frames will be willing to trade off a little in product durability to be part of the environmental solution.

“Taking out the technical jargon,” Piper said, “our durability standards are all about that unfortunate basketball to the face in the school yard.” He noted that playing with many recycled materials brings a few challenges, and that Dresden is still searching for the right additive to increase the strength of the weld lines in the frames made from recycled LDPE milk bottles and HDPE keg caps. It has partly addressed the strength problem by blending polypropylene with the polyethylene, but that makes end-of-life recycling a bigger challenge.

So Dresden has set up a closed-loop system with Melbourne-based Replas Australia, which can successfully recycle such mixed plastics into useful products such as outdoor furniture and decking. Over the past 20 years, Replas has grown from a waste collector and mixed-plastics recycler into one of the country’s leading plastic product manufacturers in its own right.

Piper says that, “So far we’ve produced fully recyclable glasses, even replacing the hinge with a plastic pin, so that with our take-back program all our glasses at the end of their life – along with our industrial waste – will be turned into glasses cases.” Instead of a classic screw hinge, the frustrating weak point on most glasses, Dresden frames have a plastic hinge ‘pin’ that allows one to interchange any parts without the need for tools, and the arms and frames can be pieced together in any combination. The firm currently makes its hinge system from a bio-based copolyester called Ecozen, which it sources from SK Chemicals in South Korea.

The firm already is selling glasses made from the above-noted types of recycled plastics and, by working with companies such as compounder Duromer Products Pty. Ltd., they continue to work to achieve 100 percent recycled content.

Separately, Dresden is thrilled with its recent success with using discarded fishing nets, washed up on the beach in Arnhem Land on the country’s northern coast. “Our ghost net nylon-6 frames are fantastically strong at the weld lines,” said Piper, “despite [the waste plastic] having floated around the Pacific for years on end.”

Over the coming year, Piper said, the firm plans to launch a number of “ranges,” but unlike others in the eyeglass industry, all will be of the same style. “What’s new with each range is instead the material and story behind them. … There is so much to be recycled with so many stories to tell,” Piper notes.

He explained that his company’s eyeglass system is built around a single frame style in four sizes in a vast array of colors. Customers find the best fit in the color combos that they choose. All parts are interchangeable.

The project began with Dresden asking Sydney-based industrial design firm Vert to research Australians’ face shapes and sizes and test frame styles via 3D-printed prototypes. One classic favorite has become Dresden’s universal frame. From there, they realized that frame sets could easily be customized with interchangeable parts. The result was four frame sizes and four lengths of arm, to accommodate different fits.

The system allows customers to customize their look by changing out frame and arm colors and materials. As for the interchangeable lenses – supplied by Zeiss Vision Care, a local arm of the century-old German optics pioneer – Dresden cuts them in-store to allow for additional flexibility, functionality and convenience. It makes its plastic lenses from PPG Industries Inc.’s CR-39 allyl diglycol carbonate monomer.

Dresden has teamed up with manufacturing partner Astor Industries, an injection molder and plastics plater in western Sydney that previously focused almost exclusively on making car parts. But with Australia’s auto industry shrinking fast, the firm was happy to branch out into the molding of eyewear.

Dresden itself, meanwhile, has what it calls a “hobby” benchtop injection molding machine – from U.S.-based Medium Machinery LLC – in its Newtown workshop. It’s there, the firm says, that “we’ve brewed up experimental frames on the spot – one-offs made from milk bottle lids, plastic ocean waste, or even plastic keys from a discarded keyboard. We’ll give anything a try.”

This past spring Dresden signed leases on space in Sydney for two more retail shops. Once these are up and running, Piper said he hopes to build one of the Precious Plastic machines – referring to the do-it-yourself plastic recycling machine created and offered for free online as an open-source design by Dutch entrepreneur Dave Hakkens (see http://bit.ly/Precious_Plastic).

“We’ve built a trailer that will take eye health services and thousands of Carl Zeiss prescription lenses to rural Australia where these services are very limited, to test eyes and fulfil prescriptions on the road. The dream,” Dresden says, “is to have a mini DIY granulator and injection molder recycling people’s waste into glasses frames along the way.”

And, speaking of waste, Piper noted that the company’s leaders realized very early on what a negative impact they could have on the environment if they were to manufacture plastic frames irresponsibly. “This realization drove our manufacturing process and today one of the first things you’ll notice when you walk into our shops is that the colors never end.

“On our first day of manufacturing,” he recalled, “we couldn’t believe how much material was wasted in purging machines from one color to the next, so instead of stubbornly sticking to a set color range, we started capturing all the transitions between each color. The result is an endless color range with unique pieces that might never be repeated.”

“To us,” the company notes on its website, “quality doesn’t mean perfection down to the last micron or shade of Pantone. Yes, we’ve got 16 regular colors in our range. But between every run, we’re looking forward to some happy accidents.”

“The plan,” Piper noted, “is to bring Dresden to all major cities around Australia by next year, with our trailer on the road bringing eye health services and Dresden specs to Australians living in more remote communities. Then it’s onwards! It’s an exciting unknown, but we’re dreaming of L.A., Vancouver, Taipei, Barcelona, just to get started. 2017 will be running at a million miles an hour and the liberty of our mobile trailer means we really can be anywhere.”

“We’re on a mission,” declares the firm. Regardless of how things play out, it would be fair to say – with tongue only partly in cheek – that Dresden Optics is a company with a vision.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A 35-year B2B media veteran, Robert Grace was the founding editor of Plastics News in 1989. An ardent design advocate, he struck out on his own in 2014 and founded RC Grace LLC (www.rcgrace.com), a consultancy through which he offers a variety of services – from content creation, freelance editing, marketing and PR, event organizing, and business development.

A 35-year B2B media veteran, Robert Grace was the founding editor of Plastics News in 1989. An ardent design advocate, he struck out on his own in 2014 and founded RC Grace LLC (www.rcgrace.com), a consultancy through which he offers a variety of services – from content creation, freelance editing, marketing and PR, event organizing, and business development.