Effectiveness of Antegrade Access in Bladder Tumors With Inaccessible Urethra

Abdul Rouf Khawaja, MS DNB (Urology),1,2 Tanveer Iqbal Dar, MS DNB (Urology),1 Sajad Maik, MS DNB (Urology),2 Javaid Magray, MS (Surgery),2 Ashiq Bhat, MS, Mch trainee (Urology),2 Arif Hameed Bhat, Mch (Urology),1 Mohd.Saleem Wani, Mch (Urology),1 Baldev Singh Wazir, MS, FICS (Urology)1

1Consultant; 2Department of Urology Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences and Department of Urology, Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital, Srinagar, India

Inaccessible urethra with no retrograde endoscopic access due to multiple/diffuse strictures or multiple urethrocutaneous fistulas with acute urinary retention due to posturethral instrumentation (transurethral resection of bladder tumor [TURBT], or TURBT with transurethral resection of the prostate [TURP]), is a rare entity. Management of such a case with a bladder tumor for TURBT/surveillance cystoscopy poses a great challenge. The authors present 12 cases of bladder tumor with inaccessible urethra, 10 cases due to multiple strictures (post-TURBT and/or TURP), and 2 cases due to urethrocutaneous fistulas (post-TURBT), who presented to our emergency department with acute urinary retention. Emergent suprapubic catheterization was used as a temporary treatment method.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(4):241-245 doi: 10.3909/riu0677]

© 2016 MedReviews®, LLC

Effectiveness of Antegrade Access in Bladder Tumors With Inaccessible Urethra

Abdul Rouf Khawaja, MS DNB (Urology),1,2 Tanveer Iqbal Dar, MS DNB (Urology),1 Sajad Maik, MS DNB (Urology),2 Javaid Magray, MS (Surgery),2 Ashiq Bhat, MS, Mch trainee (Urology),2 Arif Hameed Bhat, Mch (Urology),1 Mohd.Saleem Wani, Mch (Urology),1 Baldev Singh Wazir, MS, FICS (Urology)1

1Consultant; 2Department of Urology Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences and Department of Urology, Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital, Srinagar, India

Inaccessible urethra with no retrograde endoscopic access due to multiple/diffuse strictures or multiple urethrocutaneous fistulas with acute urinary retention due to posturethral instrumentation (transurethral resection of bladder tumor [TURBT], or TURBT with transurethral resection of the prostate [TURP]), is a rare entity. Management of such a case with a bladder tumor for TURBT/surveillance cystoscopy poses a great challenge. The authors present 12 cases of bladder tumor with inaccessible urethra, 10 cases due to multiple strictures (post-TURBT and/or TURP), and 2 cases due to urethrocutaneous fistulas (post-TURBT), who presented to our emergency department with acute urinary retention. Emergent suprapubic catheterization was used as a temporary treatment method.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(4):241-245 doi: 10.3909/riu0677]

© 2016 MedReviews®, LLC

Effectiveness of Antegrade Access in Bladder Tumors With Inaccessible Urethra

Abdul Rouf Khawaja, MS DNB (Urology),1,2 Tanveer Iqbal Dar, MS DNB (Urology),1 Sajad Maik, MS DNB (Urology),2 Javaid Magray, MS (Surgery),2 Ashiq Bhat, MS, Mch trainee (Urology),2 Arif Hameed Bhat, Mch (Urology),1 Mohd.Saleem Wani, Mch (Urology),1 Baldev Singh Wazir, MS, FICS (Urology)1

1Consultant; 2Department of Urology Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences and Department of Urology, Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital, Srinagar, India

Inaccessible urethra with no retrograde endoscopic access due to multiple/diffuse strictures or multiple urethrocutaneous fistulas with acute urinary retention due to posturethral instrumentation (transurethral resection of bladder tumor [TURBT], or TURBT with transurethral resection of the prostate [TURP]), is a rare entity. Management of such a case with a bladder tumor for TURBT/surveillance cystoscopy poses a great challenge. The authors present 12 cases of bladder tumor with inaccessible urethra, 10 cases due to multiple strictures (post-TURBT and/or TURP), and 2 cases due to urethrocutaneous fistulas (post-TURBT), who presented to our emergency department with acute urinary retention. Emergent suprapubic catheterization was used as a temporary treatment method.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(4):241-245 doi: 10.3909/riu0677]

© 2016 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Suprapubic cystostomy • Inaccessible urethra • Bladder tumors • Tract seedling

Key words

Suprapubic cystostomy • Inaccessible urethra • Bladder tumors • Tract seedling

Most patients presented with acute urinary retention and failed catheterization and urethrocutaneous fistula, and one patient presented with failed optical internal urethrotomy for urethral stricture with extravasation and retention.

Main Points

• Inaccessible urethra with no retrograde endoscopic access is a rare urologic finding. It can be due to multiple/ diffuse strictures or multiple urethrocutaneous fistulas with acute urinary retention due to posturethral instrumentation, transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT), or TURBT with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

• Bladder tumors are the most common neoplasm of the lower urinary tract, accounting for 6% of all malignancies in men and 2% of those in women. A majority of patients present with gross painless hematuria, usually as the sole presenting symptom. Initial symptoms of urothelial cancer of the bladder (UCB) include microhematuria, painless macrohematuria, and/or irritative voiding symptoms..

• The term inaccessible urethra means all prescribed endoscopic interventions have failed to relieve acute painful retention. Suprapubic cystostomy is a relatively safe and common procedure in urologic practice; it is also used in cases of genitourinary trauma, with few complications. It provides effective urinary diversion and drainage.

• Advantages of suprapubic diversion are that it is easy, provides quick relief, is practiced by all urologists, and can be done under local anesthesia.

• For perineal urethrostomy, the patient requires either regional or general anesthesia, and the procedure needs to be done in the operating room. During urethrostomy, the urethra is exposed to nonurothelial surfaces with a theoretical risk of tumor seeding.

Main Points

• Inaccessible urethra with no retrograde endoscopic access is a rare urologic finding. It can be due to multiple/ diffuse strictures or multiple urethrocutaneous fistulas with acute urinary retention due to posturethral instrumentation, transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT), or TURBT with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

• Bladder tumors are the most common neoplasm of the lower urinary tract, accounting for 6% of all malignancies in men and 2% of those in women. A majority of patients present with gross painless hematuria, usually as the sole presenting symptom. Initial symptoms of urothelial cancer of the bladder (UCB) include microhematuria, painless macrohematuria, and/or irritative voiding symptoms..

• The term inaccessible urethra means all prescribed endoscopic interventions have failed to relieve acute painful retention. Suprapubic cystostomy is a relatively safe and common procedure in urologic practice; it is also used in cases of genitourinary trauma, with few complications. It provides effective urinary diversion and drainage.

• Advantages of suprapubic diversion are that it is easy, provides quick relief, is practiced by all urologists, and can be done under local anesthesia.

• For perineal urethrostomy, the patient requires either regional or general anesthesia, and the procedure needs to be done in the operating room. During urethrostomy, the urethra is exposed to nonurothelial surfaces with a theoretical risk of tumor seeding.

Bladder tumors are the most common neoplasm of the lower urinary tract, comprising 6% of all malignancies in men and 2% of those in women.1 A majority of patients present with gross painless hematuria, usually as the sole presenting symptom.2 Bladder carcinoma is unique among human neoplasms in that many of its etiologic factors are known; the urologist should be aware of the possible occupational exposures to urothelial carcinogens.3 Initial symptoms of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (UCB) include microhematuria, painless macrohematuria, and/or irritative voiding symptoms, and require further investigation. Carcinoma in situ of the bladder causes irritative lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) more often than does papillary UCB. Histopathologic evaluation is necessary to assess stage and grade with sufficient certainty after the appearance of bladder tumors.4 Bladder tumors spread by implantation in abdominal wounds, denuded epithelium, resected prostatic fossa, or traumatized urethra5; implantation occurs most often with high-grade tumors.

Material and Methods

A case series was conducted in the department of urology at the Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, and Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital in Srinagar, India, from December 2004 to December 2014. Data were collected from 12 patients diagnosed with bladder tumors. Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) alone was performed in nine patients and TURBT with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) was performed in three. Dates of surgeries (TURBT), intraoperative/ radiologic and histopathologic findings, intravesical chemotherapy, and surveillance cystoscopy schedule with follow-up were recorded for all patients. Duration of post-TURBT obstructive and irritative LUTS was also recorded. All patients presented to the emergency department with acute urinary retention with failed catheterization. Two patients presented with urethrocutaneous fistula and one patient presented with extravasation and urinary retention after endoscopic intervention (optical internal urethrotomy). Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, kidney function test, ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (KUB), retrograde urethrogram, and optional KUB contrast-enhanced computed tomography, were done in all patients. All patients underwent suprapubic cystostomy (SPC) under local anesthesia. Initially, a Reuters trocar was used to perform the cystostomy and an 8F or 10F Foley catheter was indwelled under local anesthesia. We now use a simple percutaneous technique with a 16-gauge grey cannula (outer diameter 1.5F, length 45 mm) and a 0.025- to 0.035-inch guidewire inserted into the bladder through angiographic catheter. A 6F- to 8F feeding tube is introduced into the bladder using the Blitz technique to avoid ragged margins. All patients were given oral quinolones and anti-inflammatory drugs and were discharged on the same day. A definitive procedure to correct the inaccessible urethra (staged urethroplasty) was done within 1 to 2 months after the SPC. Any recurrence of bladder tumor on surveillance cystoscopy was managed via perineal urethrostomy (staged urethroplasty) followed by intraoperative chemotherapy (intravesical mitomycin-C, 40 mg).

Follow-up

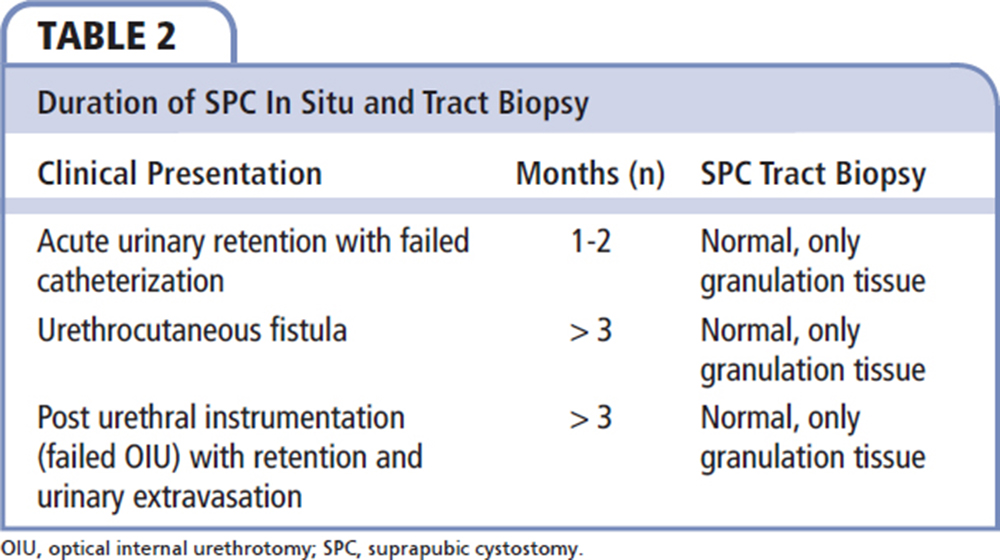

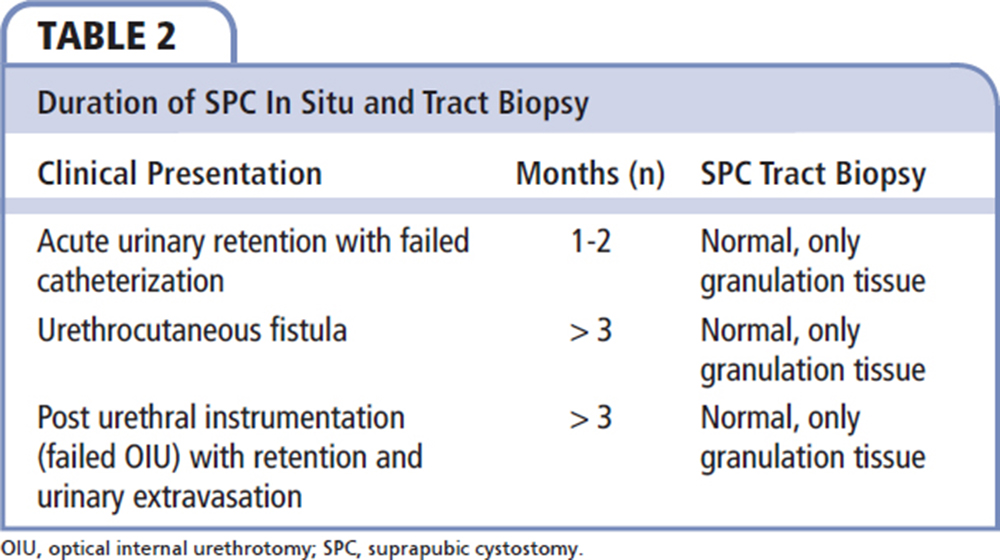

The first follow-up visit was made 1 week after SPC. Any maintenance intravesical chemotherapy, either mitomycin or bacillus Calmette-Guérin, was given via SPC. The drug was administered intravesically for 1 hour; it was advisable to keep patients in the prone position to maintain contact with the suprapubic puncture site. An SPC tract biopsy was performed in all patients after an interval of 1 to 2 months. Local examination of the SPC site was made at each visit to identify any palpable mass or skin changes. All patients were given a helpline number to call if any untoward event occurred while awaiting the second staged urethroplasty.

Results

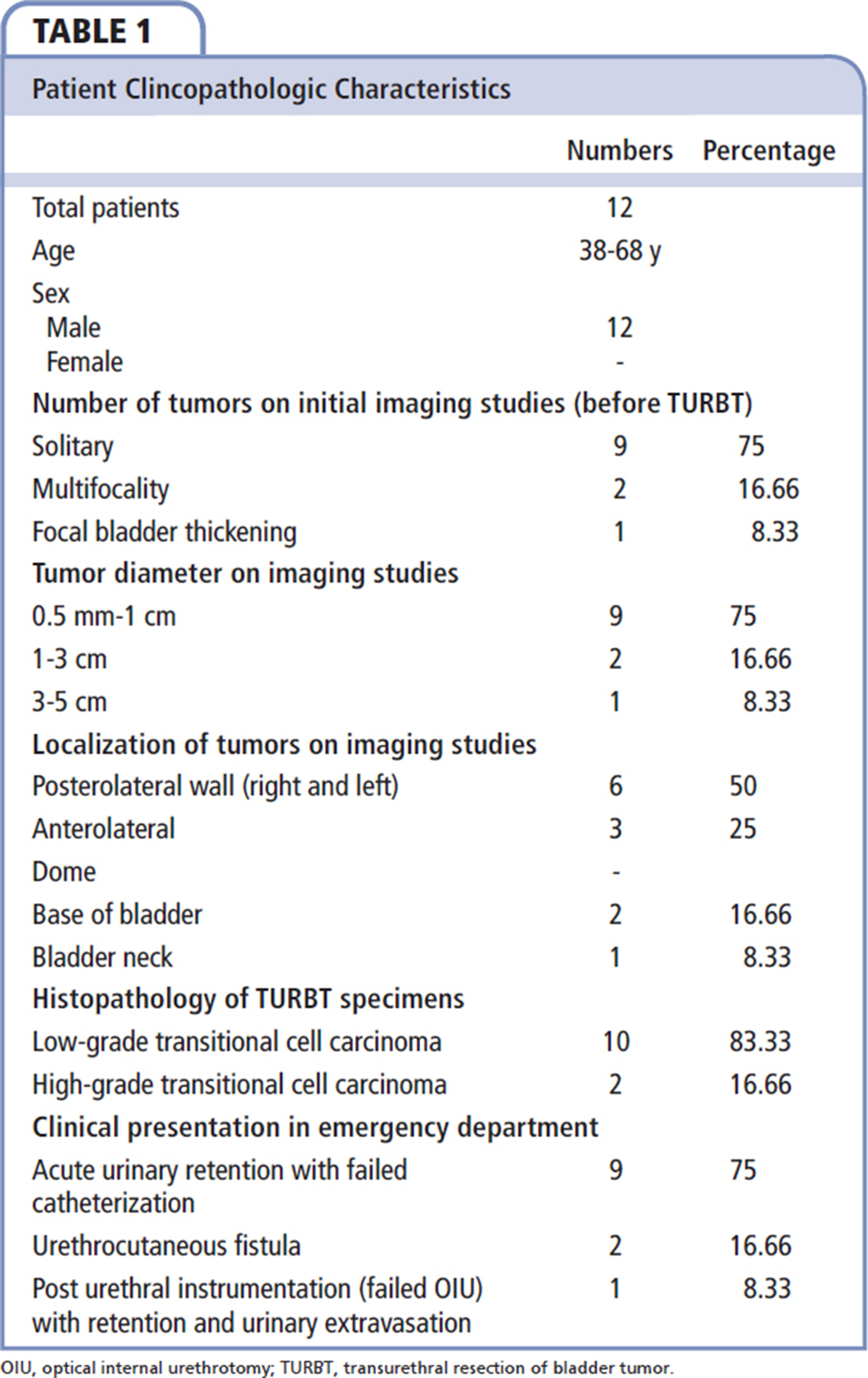

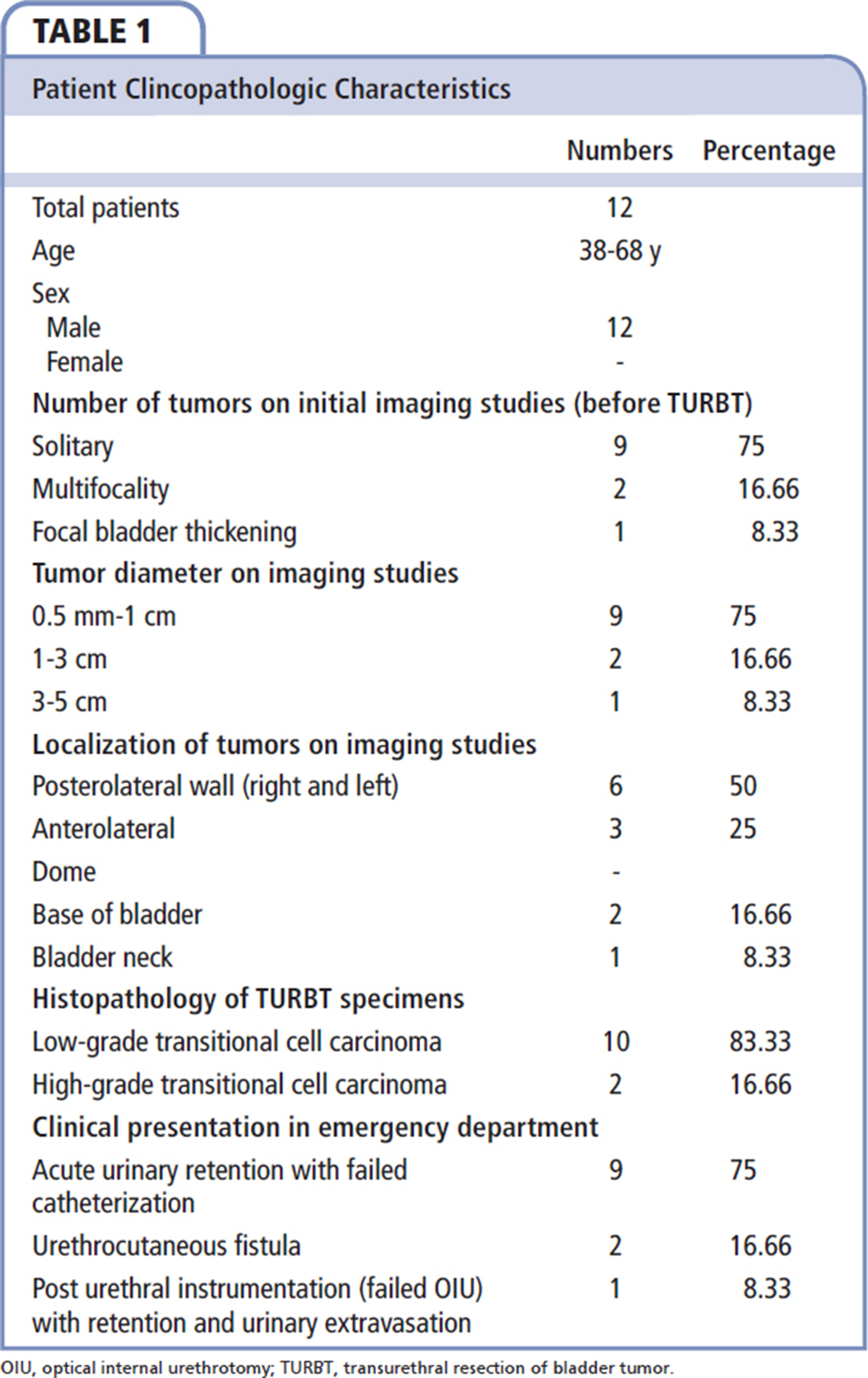

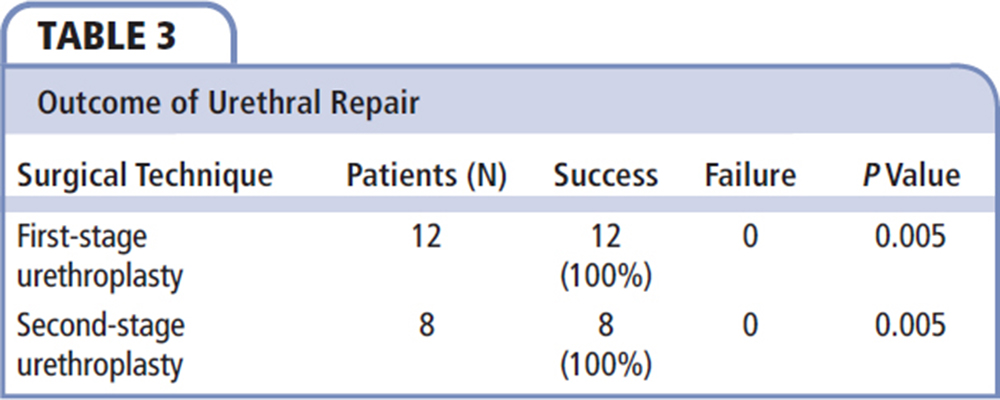

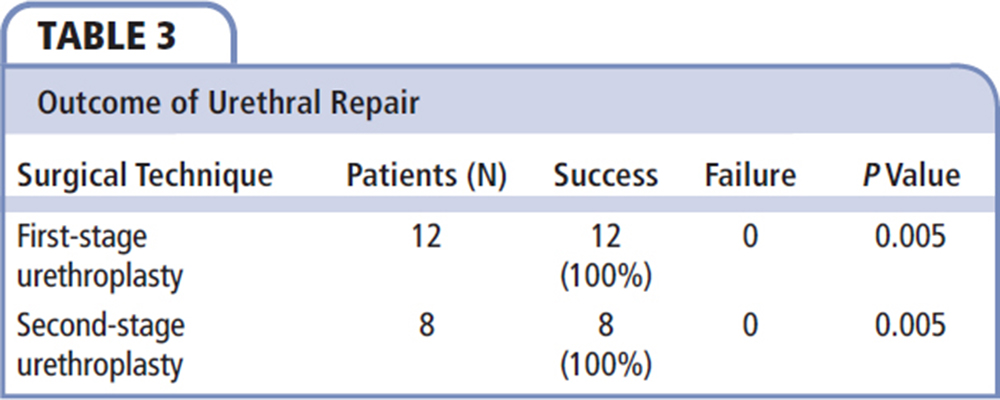

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the 12 patients enrolled in our study are shown in Table 1. They ranged in age from 38 to 68 years. The majority of bladder tumors were solitary (75%) and located posterolaterally (50%). The majority of resected bladder tumors were low-grade translational cell carcinoma (83.33%), and the rest were high-grade translational cell carcinoma (16.66%). Most patients presented with acute urinary retention and failed catheterization (75%) and urethrocutaneous fistula (16.66%), and one patient presented with failed optical internal urethrotomy for urethral stricture with extravasation and retention (8.33%). In all patients, a tract-site biopsy was taken after a 1- to 2-month interval; normal granulation tissue was seen on histopathologic examination (Table 2). All patients underwent staged urethroplasty (Table 3) with a 100% success rate (P < 0.005). A buccal mucosal graft (labiobuccal) was harvested and transferred to the urethral plate in initial stage 1 urethroplasty, and was tubularized after 6 months in stage 2 urethroplasty. A majority of the strictures were long and dense in the bulbar and penoscrotal region. No donor site morbidity was noted, and the donor site was left open. Betadine gargles were used during the postoperative period. After a follow-up period of 10 years, none of the patients had any ultrasound-documented abnormality or palpable abnormality at the cystostomy site. After presenting with urethrocutaneous fistula, one patient—in whom the tract-site biopsy result was normal—died after 6 months of SPC.

Discussion

SPC is a noncontinent, direct drainage of the bladder with inaccessible urethra; it may be accomplished by an open or by punch technique with a trocar,6 or by percutaneous methods using the Seldinger wire technique. SPC is a relatively safe and common procedure in urologic practice; it is also used in cases of genitourinary trauma, with few complications. It provides effective urinary diversion and drainage.7 The term inaccessible urethra means all prescribed endoscopic interventions have failed to relieve acute painful retention.

Bladder tumors spread by implantation in abdominal wounds and denuded epithelium. Implantation occurs most commonly with high-grade tumors. The ability of transitional carcinoma tumor cells to implant on urothelial surfaces is well established.8,9 The key factor in tumor implantation is the size of the initial tumor inoculum, which is similar to an infectious process.10 Intravesical tumor inoculum occurring at the time of transurethral surgery results from tumor cell adherence to fibrin at the sites of urothelial injury.11 An earlier understanding was that the bladder tumors spread by implantation, and combining TURP with TURBT could increase the chance of implantation of tumor cells in the raw area created by TURP.8,12 This topic was reviewed by Kouriefs and colleagues13 in 2008; they concluded that undertaking TURBT and TURP simultaneously is not an unsafe surgical practice. In their study, the overall incidence of tumor recurrence in the bladder neck and prostate was similar in the case and control groups.13 The incidence was not significantly different even when comparing different grades of tumor or multiplicity. In our series, all patients were diagnosed with bladder tumors. TURBT was performed in all patients, and they received either chemotherapy or immunotherapy, and all were on regular surveillance cystoscopy. Retrograde urethrogram was performed in all patients to assess the urethra for any possible endoscopic intervention to avoid antegrade access. Micturating cystourethrogram was not possible in cases of acute retention/ sore bladder. No flexible cystoscope is available in our hospital; however, semirigid ureteroscopy was attempted in several patients, but no access to the bladder via the urethra was possible. To avoid stage migration/cutaneous involvement of urothelial tumors, patients were given two options: either bilateral percutaneous nephrostomy or perineal urethrostomy. Percutaneous nephrostomy for diversion is challenging in a normal upper urinary tract, and requires intervention to relieve acute urinary retention. However, perineal urethrostomy exposes nonurothelial surfaces. Moreover, in several patients additional TURP was performed; the possibility of bladder neck contracture could be ruled out in cases of acute urinary retention. In view of the above choice, for temporary and immediate resolution, the simple and easy approach to an inaccessible urethra was via suprapubic diversion. A self-retaining Foley catheter was avoided to prevent bladder spasm, the possibility of increased intravesical pressure, and the theoretical chance of tumor seedling. Bodner and colleagues14 concluded that high intravesical pressure at the time of resection could increase the likelihood of tumor spread. A small feeding tube was inserted to minimize the surface area of the bladder, as given injury represents a saturable site to which a limited number of abnormal cells may adhere. Tract-site biopsy (at multiple sites) was taken after 1 to 2 months and sent for histopathologic examination, with special emphasis on noting any cancer cells. A suprapubic tract was maintained for at least 1 to 2 months, until staged urethroplasty was done. No repeat biopsy was possible, as the feeding tube was removed after staged urethroplasty.

Advantages of suprapubic diversion are that it is easy, provides quick relief, is practiced by all urologists, and can be done under local anesthesia. In cases of suspicious space-occupying lesions in the bladder, ultrasound can be helpful to avoid needle advancement into the tumor during suprapubic diversion. One drawback of transabdominal ultrasound is that carcinoma in situ is not visible. Chemotherapy/immunotherapy can be given with surveillance cystoscopy in cases of inaccessible urethra via SPC. Moreover, the SPC tract site can be self-examined by the patient for any swelling and skin changes, and is also accessible to general practitioners and treating urologists.

For perineal urethrostomy, the patient requires either regional or general anesthesia, and the procedure needs to be done in the operating room. During urethrostomy, the urethra is exposed to nonurothelial surfaces with a theoretical risk of tumor seeding; subsequent urethroplasty is difficult. In patients in whom additional TURP is performed, bladder neck contracture is a possibility and requires either cold knife incision or urethral dilatation, which is lengthy for a patient with acute retention. To our knowledge, no such study is found in the literature. Based on our study, we strongly believe percutaneous suprapubic diversion for inaccessible urethra is a viable temporary/emergency option until a definitive procedure can be planned on an elective basis.

Conclusions

SPC is an effective, inexpensive, easy mode of access for bladder tumors with difficult urethral access for urinary retention and urethrocutaneous fistula with inaccessible urethra. It allows us to effectively screen the bladder using cystoscope and cytology, and also supply intravesical chemotherapy. ![]()

References

- Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51: 15-36.

- Gardner BP, Doyle PT. Symptoms of bladder carcinoma. J R Coll Gen Pract.1987;37:367.

- Vineis P, Simonato L. Proportion of lung and bladder carcinoma in males resulting from occupation. Arch Environ Health. 1991;46:6-15.

- Amin MB, McKenney JK, Paner GP, et al; International Consultation on Urologic Disease-European Association of Urology Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: Pathology. Eur Urol. 2013;63:16-35.

- McDougal WS, Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, et al, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:2426.

- Hilton P, Stanton SL. Suprapubic catheterization. Br Med J. 1980;281:1261-1263.

- Badlani GH, Douenias R, Smith AD. Percutaneous bladder procedures. Urol Clin North Am. 1990;17:67-73.

- Weldon TE, Soloway MS. Susceptibility of urothelium to neoplastic cellular implantation. Urology. 1975;5:824-827.

- Soloway MS, Masters S. Urothelial susceptibility to tumor cell implantation: influence of cauterization. Cancer. 1980;46:1158-1163.

- Porter EH, Hewitt HB, Blake ER. The transplantation kinetics of tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 1973;27;55-62.

- See WA, Miller JS, Williams RD. Pathophysiology of transitional tumor cell adherence to sites of urothelial injury: mechanism mediating intravesical recurrence due to implantation. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5414-5418.

- Green LF, Yalowitz PA. The advisability of concomitant transurethral excision of vesical neoplasm and prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1972;107:445-447.

- Kouriefs C, Loizides S, Mufti G. Simultaneous transurethral resection of bladder tumor and prostate: is it safe? Urol Int. 2008;81:125-128.

- Bodner H, Howard AH, Kaplan JH, Ross SC. Cystometry during and cystography after transurethral resection of bladder tumor. The bladder mucosal water barrier: preliminary report. J Surg Res. 1961;1: 72-76.