Target Audience

The educational design of this activity addresses the needs of urologists associated with large group practices involved in the treatment of patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Statement of Need/Program Overview

Emerging therapies have shown potential utility within the treatment paradigm. A program focusing on the role of novel radiopharmaceuticals in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer is critical. This program will focus on the current standard of care in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), and review the role of both α- and β- emitting therapies in the treatment of CRPC, and their potential utility in different phases of the current treatment paradigm.

Educational Objectives

After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Discuss the clinical relevance of skeletal-related events in CRPC and approved therapies that are effective in preventing these events

- Review NCCN Guidelines and Best Standard of Care (BSC) for men with CRPC

- Identify emerging radio-oncologic therapies and mechanisms of action with regard to the treatment of CRPC and bone metastases

- Identify the role of radiopharmaceuticals in the treatment paradigm for CRPC

- Discuss the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of men with CRPC and bone metastases

Faculty

Paul Sieber, MD

Lancaster Urology, Lancaster, PA

Physician Accreditation Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of Global Education Group (Global) and MRCME, LLC. Global is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physician Credit Designation

Global Education Group designates this enduring for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Global Contact Information

For information about the accreditation of this program, please contact Global at 303-395-1782 or inquire@globaleducationgroup.com.

Instructions to Receive Credit

In order to receive credit for this activity, the participant must complete the post-test available online at mrcme-online.com. The passcode for this activity is urology001.

System Requirements

PC

Microsoft Windows 2000 SE or above.Flash Player Plugin (v7.0.1.9 or greater)Internet Explorer (v5.5 or greater), or FirefoxAdobe Acrobat Reader*

MAC

MAC OS 10.2.8Flash Player Plugin (v7.0.1.9 or greater)SafariAdobe Acrobat Reader*Internet Explorer is not supported on the Macintosh.

*Required to view printable (PDF) version of the lesson.

Fee Information & Refund/Cancellation Policy

There is no fee for this educational activity.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

Global Education Group (Global) requires instructors, planners, managers and other individuals and their spouse/life partner who are in a position to control the content of this activity to disclose any real or apparent conflict of interest they may have as related to the content of this activity. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted by Global for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies mentioned in the materials or used as the basis for content, and appropriateness of patient care recommendations.

The faculty reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Name of Faculty or Presenter

Reported Financial Relationship

Paul Sieber, MD

Honoraria: Dendreon, Janssen

Speakers’ Bureau: Bayer, Dendreon, Medivation/Astellas, Janssen, Ferring, Watson, Amgen

The planners and managers reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Name of Planner or Manager and Reported Financial Relationship

Ashley Marostica, RN, MSN Nothing to disclose

Amanda Glazar, PhD Nothing to disclose

Merilee Croft Nothing to disclose

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. Global Education Group (Global) and MRCME, LLC do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications.

The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization associated with this activity. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of patient conditions and possible contraindications on dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

Target Audience

The educational design of this activity addresses the needs of urologists associated with large group practices involved in the treatment of patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Statement of Need/Program Overview

Emerging therapies have shown potential utility within the treatment paradigm. A program focusing on the role of novel radiopharmaceuticals in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer is critical. This program will focus on the current standard of care in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), and review the role of both α- and β- emitting therapies in the treatment of CRPC, and their potential utility in different phases of the current treatment paradigm.

Educational Objectives

After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Discuss the clinical relevance of skeletal-related events in CRPC and approved therapies that are effective in preventing these events

- Review NCCN Guidelines and Best Standard of Care (BSC) for men with CRPC

- Identify emerging radio-oncologic therapies and mechanisms of action with regard to the treatment of CRPC and bone metastases

- Identify the role of radiopharmaceuticals in the treatment paradigm for CRPC

- Discuss the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of men with CRPC and bone metastases

Faculty

Paul Sieber, MD

Lancaster Urology, Lancaster, PA

Physician Accreditation Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of Global Education Group (Global) and MRCME, LLC. Global is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physician Credit Designation

Global Education Group designates this enduring for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Global Contact Information

For information about the accreditation of this program, please contact Global at 303-395-1782 or inquire@globaleducationgroup.com.

Instructions to Receive Credit

In order to receive credit for this activity, the participant must complete the post-test available online at mrcme-online.com. The passcode for this activity is urology001.

System Requirements

PC

Microsoft Windows 2000 SE or above.Flash Player Plugin (v7.0.1.9 or greater)Internet Explorer (v5.5 or greater), or FirefoxAdobe Acrobat Reader*

MAC

MAC OS 10.2.8Flash Player Plugin (v7.0.1.9 or greater)SafariAdobe Acrobat Reader*Internet Explorer is not supported on the Macintosh.

*Required to view printable (PDF) version of the lesson.

Fee Information & Refund/Cancellation Policy

There is no fee for this educational activity.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

Global Education Group (Global) requires instructors, planners, managers and other individuals and their spouse/life partner who are in a position to control the content of this activity to disclose any real or apparent conflict of interest they may have as related to the content of this activity. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted by Global for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies mentioned in the materials or used as the basis for content, and appropriateness of patient care recommendations.

The faculty reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Name of Faculty or Presenter

Reported Financial Relationship

Paul Sieber, MD

Honoraria: Dendreon, Janssen

Speakers’ Bureau: Bayer, Dendreon, Medivation/Astellas, Janssen, Ferring, Watson, Amgen

The planners and managers reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Name of Planner or Manager and Reported Financial Relationship

Ashley Marostica, RN, MSN Nothing to disclose

Amanda Glazar, PhD Nothing to disclose

Merilee Croft Nothing to disclose

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. Global Education Group (Global) and MRCME, LLC do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications.

The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization associated with this activity. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of patient conditions and possible contraindications on dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

Target Audience

The educational design of this activity addresses the needs of urologists associated with large group practices involved in the treatment of patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Statement of Need/Program Overview

Emerging therapies have shown potential utility within the treatment paradigm. A program focusing on the role of novel radiopharmaceuticals in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer is critical. This program will focus on the current standard of care in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), and review the role of both α- and β- emitting therapies in the treatment of CRPC, and their potential utility in different phases of the current treatment paradigm.

Educational Objectives

After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Discuss the clinical relevance of skeletal-related events in CRPC and approved therapies that are effective in preventing these events

- Review NCCN Guidelines and Best Standard of Care (BSC) for men with CRPC

- Identify emerging radio-oncologic therapies and mechanisms of action with regard to the treatment of CRPC and bone metastases

- Identify the role of radiopharmaceuticals in the treatment paradigm for CRPC

- Discuss the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of men with CRPC and bone metastases

Faculty

Paul Sieber, MD

Lancaster Urology, Lancaster, PA

Physician Accreditation Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of Global Education Group (Global) and MRCME, LLC. Global is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Physician Credit Designation

Global Education Group designates this enduring for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Global Contact Information

For information about the accreditation of this program, please contact Global at 303-395-1782 or inquire@globaleducationgroup.com.

Instructions to Receive Credit

In order to receive credit for this activity, the participant must complete the post-test available online at mrcme-online.com. The passcode for this activity is urology001.

System Requirements

PC

Microsoft Windows 2000 SE or above.Flash Player Plugin (v7.0.1.9 or greater)Internet Explorer (v5.5 or greater), or FirefoxAdobe Acrobat Reader*

MAC

MAC OS 10.2.8Flash Player Plugin (v7.0.1.9 or greater)SafariAdobe Acrobat Reader*Internet Explorer is not supported on the Macintosh.

*Required to view printable (PDF) version of the lesson.

Fee Information & Refund/Cancellation Policy

There is no fee for this educational activity.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

Global Education Group (Global) requires instructors, planners, managers and other individuals and their spouse/life partner who are in a position to control the content of this activity to disclose any real or apparent conflict of interest they may have as related to the content of this activity. All identified conflicts of interest are thoroughly vetted by Global for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies mentioned in the materials or used as the basis for content, and appropriateness of patient care recommendations.

The faculty reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Name of Faculty or Presenter

Reported Financial Relationship

Paul Sieber, MD

Honoraria: Dendreon, Janssen

Speakers’ Bureau: Bayer, Dendreon, Medivation/Astellas, Janssen, Ferring, Watson, Amgen

The planners and managers reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Name of Planner or Manager and Reported Financial Relationship

Ashley Marostica, RN, MSN Nothing to disclose

Amanda Glazar, PhD Nothing to disclose

Merilee Croft Nothing to disclose

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. Global Education Group (Global) and MRCME, LLC do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications.

The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of any organization associated with this activity. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of patient conditions and possible contraindications on dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

Emerging Therapeutic for the Treatment of Skeletal-related Events Associated With Metastatic Castrate-resistant Prostate Cancer

Paul R. Sieber, MD

Lancaster Urology, Lancaster, PA

Prostate cancer is the most prevalent cancer in US and European men and the second leading cause of cancer death in those populations. It is somewhat unique in that nearly all patients who succumb to the disease will ultimately develop bone metastasis. Morbidity from bone metastasis—referred to as skeletal-related events, which include fractures, cord compression, radiation to bone, and surgery to bone—leads to significant costs and impaired quality of life. This article reviews three agents and the roles they play in the ever-changing armamentarium of treatments for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). The potential benefits of these agents are discussed, as well as the continuing use of these agents and their earlier introduction in the patient with progressive mCRPC with bone metastasis.

[ Rev Urol. 2014;16(1):10-20 doi: 10.3909/riu0609]

© 2014 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer • Skeletal-related events • Bone metastasis • Zoledronic acid • Denosumab • Radium Ra 223 dichloride

Zoledronic acid reduced bone pain compared with placebo in patients with bone metastases from CRPC, regardless of the baseline pain status, and appeared more efficacious when initiated before the onset of pain.

Main Points

• Morbidity from bone metastasis—referred to as skeletal-related events (SREs), which include fractures, cord compression, radiation to bone, and surgery to bone—leads to significant costs and impaired quality of life.

• Zoledronic acid reduced bone pain compared with placebo in patients with bone metastases from castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) regardless of the baseline pain status, and appeared more efficacious when initiated before the onset of pain. Results from the original zoledronic acid pivotal trial also suggest that this compound provided ongoing clinical benefit—regardless of the patient’s history of SREs. Thus, it is reasonable to treat patients with zoledronic acid for as long as it is tolerated or until the patient experiences a substantial decline in performance status. However, zoledronic acid was unable to demonstrate a survival advantage in this group of patients with CRPC and bone metastases.

• Denosumab significantly prolonged bone metastasis–free survival and delayed time to bone metastasis in a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. However, equally important, the overall survival did not change with this positive delay in the development of bone metastasis. Thus, the limitation of these bone-targeted agents is the lack of a survival advantage with either zoledronic acid or denosumab. Denosumab appears to be somewhat more effective and easier to tolerate than zoledronic acid because of its lesser renal toxicity and acute phase reactions. It does, however, seem to carry a slightly greater risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

• Radium Ra 223 dichloride represents an advance in bone-targeted therapies for men with CRPC and bone metastases. It marks the first agent available with the ability to both prevent SREs and prolong overall survival.

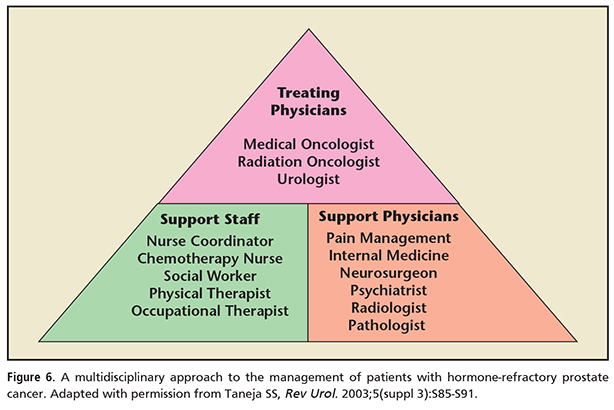

• In treating SREs associated with mCRPC, a multidisciplinary approach to treatment has been suggested. This paradigm can include treating physicians (urologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists) along with support physicians (eg, pathologists, radiologists, psychiatrists) and supportive staff (eg, nurse coordinators, social workers, physical therapists). Barriers to this suggested multidisciplinary approach may include comorbid disease, functional limitations, and/or economic/social restrictions.

Prostate cancer is the most prevalent cancer in US and European men and the second leading cause of cancer death in those populations. It is somewhat unique in that nearly all patients who have the disease will ultimately develop bone metastasis.1 Morbidity from bone metastasis—referred to as skeletal-related events (SREs), which include fractures, cord compression, radiation to bone, and surgery to bone—leads to significant costs and impaired quality of life. An estimated 241,740 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer each year in the United States1; between 9.5% and 17.8% of these patients have M0 + M1 castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).2,3

Skeletal tumor burden and fracture are both independent predictors of death in men with metastatic CRPC (mCRPC).2,3 In addition, pain is an independent prognosticator for death4; thus, agents that reduce pain may improve quality as well as quantity of life. In the past decade, three new agents have been approved in the United States for the treatment and/or prevention of SREs in men with mCRPC. However, urologists continue to under-treat this condition.5 A recent clinical trial that screened a large population of men thought to have CRPC without metastasis found nearly one third of patients to have metastatic prostate cancer.6 And a recent large clinical trial in men with mCRPC, most of whom had bone metastases, showed fewer than 50% of patients were receiving a bisphosphonate.7

This article reviews these three agents and the new roles they play in the ever-changing armamentarium of treatments for mCRPC. The potential benefits of these agents are discussed, as well as the continuing use of these agents and their earlier introduction in the patient with progressive mCRPC with bone metastasis.

Zoledronic Acid

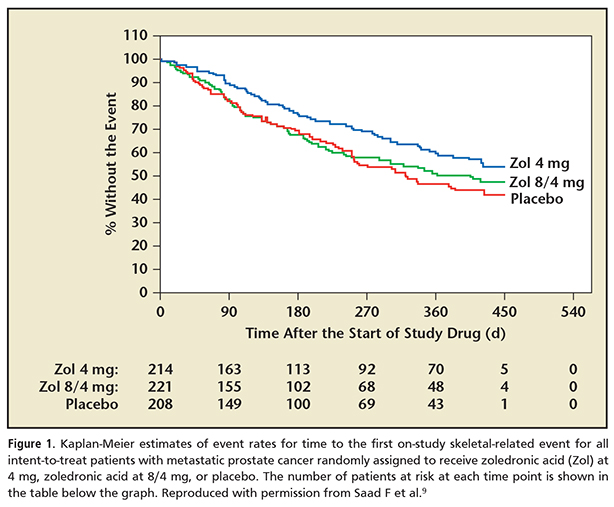

The first reference in the urology literature with regard to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and osteoporosis and/or fracture was in 1997.8 Five years later, with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of zoledronic acid, a new era in bone-targeted therapies began. Zoledronic acid was a potent intravenous bisphosphonate; it was approved to treat men with mCRPC and bone metastasis who were progressing after initial ADT. In the pivotal trial, which compared 15 doses of zoledronic acid every 4 weeks with a placebo, it was able to decrease the rate of SREs by 25% versus placebo (Figure 1).9 Zoledronic acid was clearly more effective than any other bisphosphonate10,11 and was also found to be effective in treating bone loss associated with ADT.12 In a longer-term review of zoledronic acid efficacy in patients who received 24 months of therapy, the median time to an SRE was 321 days in the placebo group versus 488 days in the zoledronic acid, 4 mg, arm. The decrease in the rate of SREs increased to 36% in the treatment group versus the placebo group.13

The results of treatment were measured by the reduction in SREs and fractures, but also by changes in bone turnover markers.5 Bone turnover markers were not only predictive of SRE/fracture risk, but also a predictor for death.14 Zoledronic acid was somewhat limited in its adoption because it had renal toxicity. It was limited in this group of generally older patients who had declines in renal function; this included both age-related and prostate cancer–specific declines. Zoledronic acid also was associated with two other side effects of clinical significance. As a potent antiresorptive, it could cause significant hypocalcemia and calcium supplements for patients were recommended. It also had an effect at the level of the mandible, causing a problem known as osteonecrosis of the jaw. Therefore, when administering this drug, calcium monitoring, an oral examination, and instruction in good oral hygiene were recommended. Acute phase reactions, such as fevers, myalgias, and fatigue were also more common than placebo in the pivotal trial for zoledronic acid.9

Zoledronic acid does cause a modest improvement in pain and analgesic scores over time. Zoledronic acid reduced bone pain compared with placebo in patients with bone metastases from CRPC, regardless of the baseline pain status, and appeared more efficacious when initiated before the onset of pain. Results from the original zoledronic acid pivotal trial also suggest that this compound provided ongoing clinical benefit, regardless of the patient’s history of SREs.13,15 Thus, it is reasonable to treat patients with zoledronic acid for as long as it is tolerated or until the patient experiences a substantial decline in performance status. However, zoledronic acid was unable to demonstrate a survival advantage in this group of patients with CRPC and bone metastases.

Denosumab

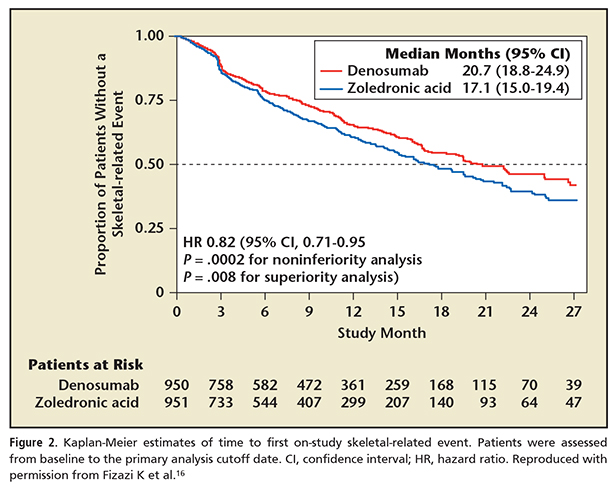

The next advance in bone-targeted therapies was the introduction of denosumab. Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody with high affinity for the receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK-ligand). It also functions as a potent antiresorptive, similar to zoledronic acid. Its mechanism of action involves blocking the feedback loop between osteoclasts and osteoblasts by binding to the RANK ligand and interrupting the binding of RANK ligand to the osteoclast. This differs from the effect zoledronic acid has on osteoclasts by its direct deposition in the bone matrix, thus blocking osteoclast activity. In the zoledronic acid versus denosumab pivotal trial, denosumab proved superior in preventing SREs (Figure 2).16,17 The median time to first SRE in the study was 3.6 months longer in the denosumab group versus the zoledronic acid group.16 This trial was similar to the prior pivotal zoledronic acid trial in design, involving men with CRPC with bone metastasis progressing after initial hormonal therapy, but differed in that it was a head-to-head study of two active drugs versus a placebo-controlled trial.

The measurement of bone turnover markers was also helpful in predicting outcomes with denosumab. One advantage of denosumab, as a monoclonal antibody, was its lack of nephrotoxicity and lack of dose reduction in moderate renal insufficiency. Similar to zoledronic acid, denosumab can also cause hypocalcemia and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Additionally, longer-term studies from prolonged use of denosumab demonstrate the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw is cumulative.18 Acute phase reactions were less common with denosumab than seen previously with zoledronic acid. Denosumab was effective in preventing fractures and bone loss associated with ADT for advanced prostate cancer.19 Finally, denosumab appears to prevent progression of pain severity and pain interference more effectively than zoledronic acid.16

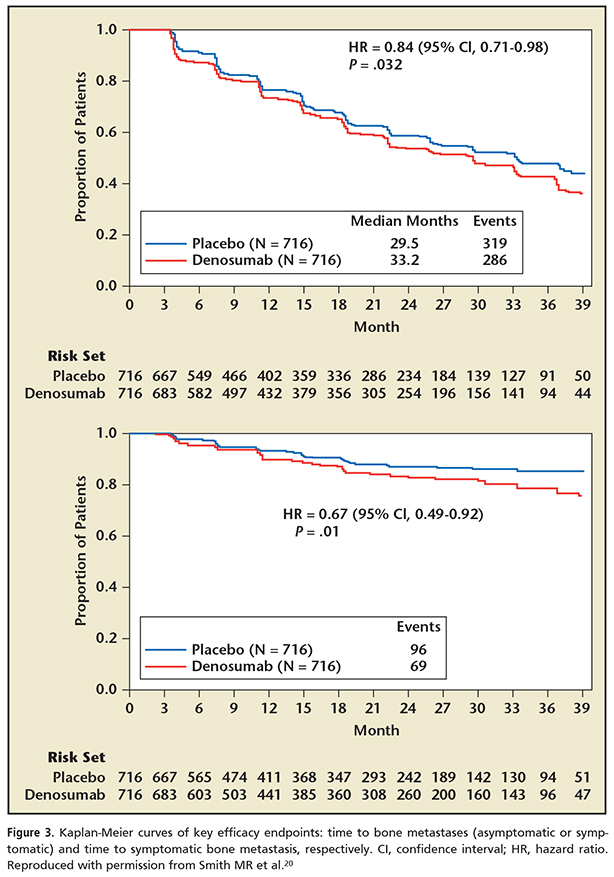

Denosumab significantly prolonged bone metastasis–free survival and delayed time to bone metastasis in a large, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.20 This provocative study looked at a cohort of high-risk prostate cancer patients who were castrate resistant but without bone metastasis. High risk was defined as rapid prostate-specific antigen (PSA) doubling times (< 10 mo) and/or a PSA > 8 ng/mL. Patients were randomized to either denosumab given at 4-week intervals or a placebo and were then monitored for the development of bone metastasis. Traditional technetium bone scans were utilized for the detection of metastasis. The results showed that denosumab significantly prolonged bone metastasis–free survival and delayed time to bone metastasis in high-risk patients (Figure 3). However, equally important, the overall survival did not change with this positive delay in the development of bone metastasis. Thus, the limitation of these bone-targeted agents is the lack of a survival advantage with either zoledronic acid or denosumab. Denosumab appears to be somewhat more effective and easier to tolerate than zoledronic acid because of its lesser renal toxicity and acute phase reactions. It does, however, seem to carry a slightly greater risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Radium Ra 223 Dichloride

Radium Ra 223 dichloride was approved in the United States in 2013 as a therapy for bone metastasis in mCRPC. It is a radioisotope and acts as a calcium mimetic. Much like osteoclast inhibitors, therapeutic radioisotopes have a predilection to accumulate in high-bone-turnover sites. Prior to the approval of radium Ra 223 dichloride, two radiopharmaceuticals were available in the US market. These included strontium-89 (Sr-89) and samarium-153 (Sm-153), both of which are β-emitting radiopharmaceuticals. These agents were approved for palliation of painful bone metastases. Multiple randomized trials have been conducted with Sr-89 and Sm-153 in patients with mCRPC.21-23

There was no demonstration of improvement in overall survival in phase 3 trials, although palliative benefits were seen that formed the basis for FDA approval. Other limitations to Sr-89 and Sm-153 include that they are renally excreted; this is not ideal in patients with genitourinary cancers. Overall, Sr-89 and Sm-153 provide some palliation of pain, but this comes at the potential expense of significant hematologic toxicities and without demonstrated overall survival benefit. As β-emitters, both of these agents can have significant myelosuppressive effects. Strontium, in particular, with a longer half-life and higher energy β particle, is more likely to cause myelosuppression than samarium. These agents are thus used as one-time therapies and can only be repeated with recovery of hematologic function.

Radium Ra 223 dichloride is a targeted α-emitting particle of short range (< 100 μm) distinctly different from Sr-89 and Sm-153. It is bound into the bone stroma, especially within the microenvironment of the osteoblastic metastases. The subsequent radiation causes a break in double-stranded DNA leading to a localized cytotoxic event. The short path of the α particle minimizes the side effects on adjacent healthy tissues and bone marrow elements. This favorable safety profile led to trials with this agent that utilized multiple repeat doses.

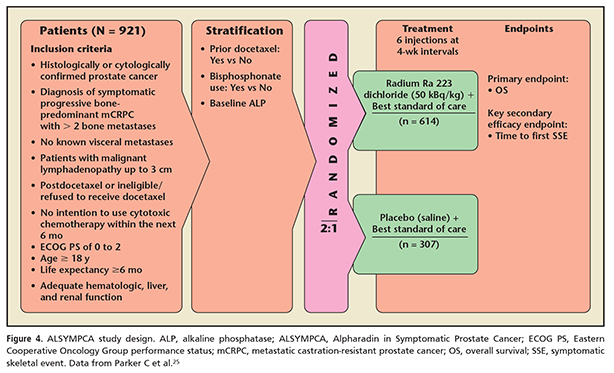

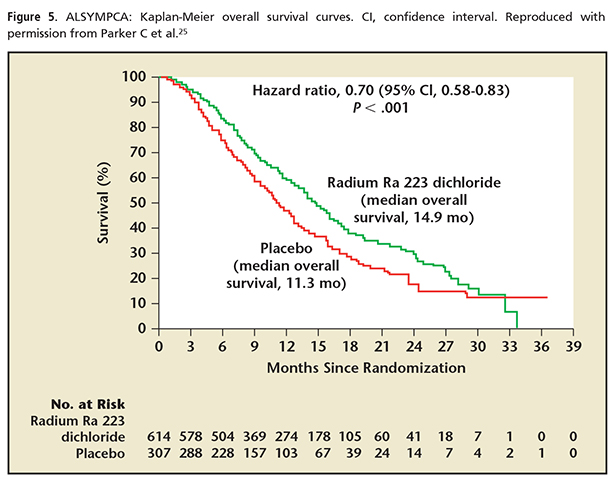

In the pivotal trial for radium Ra 223 dichloride, the Alpharadin in Symptomatic Prostate Cancer trial (ALSYMPCA),24,25 the primary endpoint was overall survival.24 The study consisted of patients with histologically confirmed progressive CRPC with bone metastases (Figure 4). The patients were required to be symptomatic with regular use of analgesics or could have received prior external beam radiotherapy in the 12 weeks prior to enrollment for palliation of bone pain. Patients had a PSA of > 5 ng/mL and none had received chemotherapy in 4 weeks prior to enrollment. No visceral metastases were allowed except malignant lymphadenopathy < 3 cm in the short axis. The endpoint was reached with a median overall survival of 14.0 months in the treatment group versus 11.2 months in the placebo group (Figure 5).24 All secondary endpoints showed benefit and included median time to first SRE, time to alkaline phosphatase progression, time to reduction or normalization of alkaline phosphatase, and time to PSA progression. The time to first SRE is even more significant when one reviews the study design. Other previous trials have included asymptomatic fractures identified on periodic bone scans/surveys as an SRE. The ALSYMPCA trial included only symptomatic fractures as an SRE. The original publication thus refers to an SRE as a SSE (a symptomatic skeletal event).

Much like sipuleucel-T,26 modest PSA responses are associated with the use of radium Ra 223 dichloride. The effects on bone turnover markers mirrors the prior results with denosumab and zoledronic acid but to a lesser degree. However, the phase 2 studies confirmed that normalization of bone turnover markers is also associated with an improvement in overall survival.4

In the ALSYMPCA trial, radium Ra 223 dichloride was administered at 4-week intervals for a total of six planned doses. The median number of doses delivered in the treatment arm was six. Interestingly, significant myelosuppression occurred in < 10% of patients.25 This point clearly demonstrates one of the key differences in α-emitting agents versus the β-emitting radiopharmaceutical agents, specifically that they cause less myelosuppression. It should also be noted that in men who had previously been treated with docetaxel, significant myelosuppression was more common.

An exploratory endpoint of the ALSYMPCA trial showed a significantly higher percentage of patients who received radium Ra 223 dichloride, as compared with those who received placebo, had a meaningful improvement in the quality of life according to the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Prostatic (FACT-P) total score (ie, an increase in the score of ≥ 10 points on a scale of 0 to 156, with higher scores indicating a better overall quality of life) during the period of study-drug administration (25% vs 16%; P = .02). The mean change in the FACT-P total score from baseline to week 16 significantly favored the radium Ra 223 dichloride group, as compared with the placebo group (22.7 vs 26.8; P = .006).25

Additional toxicity with radium Ra 223 dichloride is most commonly seen in the gastrointestinal tract. This includes nausea, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea. This occurs as a consequence of its unique excretion, predominantly into the small intestine. Very rarely did these side effects ever reach grade 3 toxicity and no grade 4 toxicities were noted.25

In the ALSYMPCA trial, a number of interesting facts are noted. Prior treatment with docetaxel was not required, and nearly 45% of patients were in this category. This is consistent with the large number of men with mCRPC who never receive chemotherapy.22,27 Therefore, the study clearly addresses an unmet need in a large proportion of men with mCRPC. All patients enrolled in this trial had symptomatic bone metastasis and yet less than one half were being treated with a bisphosphonate. This is not only typical of many clinical trials in advanced prostate cancer, but is true in clinical practice as well. Men who presented with a better Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status at baseline had a significantly better response to radium Ra 223 dichloride—yet another study that supports earlier intervention.

Radium Ra 223 dichloride represents a novel advance in bone-targeted therapies for men with CRPC and bone metastases. It marks the first agent available with the ability to both prevent SREs and prolong overall survival. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2013 Guidelines have for the first time included radium Ra 223 dichloride as a treatment for advanced mCRPC.28

Conclusions

A number of unanswered questions emerge from the addition of radium Ra 223 dichloride to the treatment paradigm for advanced prostate cancer. Some considerations include optimal treatment doses and whether repeat dosing is an option with modest cumulative myelosuppression. In addition, further research into the role of bone turnover markers may help in the sequencing of drugs because they are accurate predictors of survival.

Other areas of interest include combining radium Ra 223 dichloride with other bone-targeted agents, such as denosumab and zoledronic acid. This can correlate with the denosumab prevention trial, possibly suggesting an earlier role for radium Ra 223 dichloride because it has a proven survival advantage for metastases. On a related note, further studies may investigate if second-line hormonal agents such as abiraterone or enzalutamide should be added sequentially or concurrently to radium Ra 223 dichloride.

As seen in the ALSYMPCA trial, many physicians do not treat the majority of patients with symptomatic bone metastases with zoledronic acid or denosumab. Less than 50% of patients enrolled in the pivotal trial were using bone-targeted therapy.23 Even if they had a prior SRE and palliative external beam radiotherapy, there appears to be a benefit. In the extended zoledronic acid trials, additional efficacy was seen with longer use of bone-targeted therapy.

In treating SREs associated with mCRPC, a multidisciplinary approach to treatment has been suggested. This paradigm can include treating physicians (urologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists) along with support physicians (eg, pathologists, radiologists, psychiatrists) and supportive staff (eg, nurse coordinators, social workers, physical therapists) (Figure 6). However, many patients remain untreated, which remains a challenge to improving outcomes. Barriers to this suggested multidisciplinary approach may include comorbid disease, functional limitations, and/or economic/social restrictions.29 The treatments for advanced prostate cancer continue to evolve. The ideal sequencing or combination of drugs is yet to be determined. Bone-targeted agents continue to be underutilized for reasons that remain unclear despite their proven efficacy. There are still no specific guidelines on the optimal length of therapy for the bone-targeted agents. ![]()

References

- Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, et al; Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1148-1159.

- Noguchi M, Kikuchi H, Ishibashi M, Noda S. Percentage of the positive area of bone metastasis is an independent predictor of disease death in advanced prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:195-201.

- Oefelein MG, Resnick MI. The impact of osteoporosis in men treated for prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31:313-319.

- Harrison MR, Wong TZ, Armstrong AJ, George DJ. Radium-223 chloride: a potential new treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer patients with metastatic bone disease. Cancer Manag Res. 2013;5:1-14.

- Freedland SJ, Richhariya A, Wang H, et al. Treatment patterns in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastasis among US community-based urology group practices. Urology. 2012;80:293-298.

- Yu EY, Miller K, Nelson J, et al. Detection of previously unidentified metastatic disease as a leading cause of screening failure in a phase III trial of zibotentan versus placebo in patients with nonmetastatic, castration resistant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:103-109.

- Araujo JC, Trudel GC, Saad F, et al. Docetaxel and dasatinib or placebo in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (READY): a randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1307-1316.

- Daniell HW. Osteoporosis after orchiectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 1997;157:439-444.

- Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al; Zoledronic Acid Prostate Cancer Study Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1458-1468.

- Major PP, Lipton A, Berenson J, Hortobagyi G. Oral bisphosphonates: a review of clinical use in patients with bone metastases. Cancer. 2000;88:6-14.

- Lipton A, Small E, Saad F, et al. The new bisphosphonate, Zometa (zoledronic acid), decreases skeletal complications in both osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions: a comparison to pamidronate. Cancer Invest. 2002;20(suppl 2):45-54.

- Smith MR, Eastham J, Gleason DM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of zoledronic acid to prevent bone loss in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169: 2008-2012.

- Saad F, Eastham J. Zoledronic acid improves clinical outcomes when administered before onset of bone pain in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2010;76:1175-1181.

- Coleman RE, Major P, Lipton A, et al. Predictive value of bone resorption and formation markers in cancer patients with bone metastases receiving the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4925-4935.

- Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al; Zoledronic Acid Prostate Cancer Study Group. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96: 879-882.

- Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2011;377:813-822.

- von Moos R, Body JJ, Egerdie B, et al. Pain and health-related quality of life in patients with advanced solid tumours and bone metastases: integrated results from three randomized, double-blind studies of denosumab and zoledronic acid. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:3497-3507.

- So A, Chin J, Fleshner N, Saad F. Management of skeletal-related events in patients with advanced prostate cancer and bone metastases: incorporating new agents into clinical practice. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:465-470.

- Smith MR, Egerdie B, Hernández Toriz N, et al; Denosumab HALT Prostate Cancer Study Group. Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation

therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:745-755. - Smith MR, Saad F, Coleman R, et al. Denosumab and bone-metastasis-free survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: results of a phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:39-46.

- Serafini AN, Houston SJ, Resche I, et al. Palliation of pain associated with metastatic bone cancer using samarium-153 lexidronam: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16: 1574-1581.

- Buchali K, Correns HJ, Schuerer M, et al. Results of a double blind study of 89-strontium therapy of skeletal metastases of prostatic carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med. 1988;14:349-351.

- Lewington VJ, McEwan AJ, Ackery DM, et al. A prospective, randomised double-blind crossover study to examine the efficacy of strontium-89 in pain palliation in patients with advanced prostate cancer metastatic to bone. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:954-958.

- Parker C, Heinrich D, O’Sullivan JM, et al. Overall survival benefit and safety profile of radium-223 chloride, a first-in-class alpha-pharmaceutical: results from a phase III randomized trial (ALSYMPCA) in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) with bone metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:LBA4512.

- Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al; ALSYMPCA Investigators. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213-223.

- Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al; IMPACT Study Investigators. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411-422.

- Harris V, Lloyd K, Forsey S, et al. A population-based study of prostate cancer chemotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23:706-708.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines)®. Prostate Cancer. Version 4. 2013. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2014.

- Berger ER, Shore ND. Our prostate cancer patients need true multidisciplinary care. Oncol Times. 2005;27;4-6.