Global Resin Trends 2015: An Expert Roundtable

Previous Article Next Article

By Michael Tolinski

Given all the attention on new sources of resin feedstock (i.e., shale gas), there’s a strong need for some expert comment to put current (and future) resin trends into context. Below, four experts in the areas of polyolefin supply and demand respond to some timely questions, offering some long-range views—plus explanations about why things might not turn out as some people expect.

This year’s “Roundtable” features responses from:

- Chris Bezaire, senior vice president, Polyethylene Business, for Nova Chemicals. Bezaire joined Nova in 1994. Prior to his appointment to the management team, he served as vice president for Business and Technology Integration.

- Kent Furst, manager, Polymers & Materials Group, for The Freedonia Group, Inc. Furst has written over 50 studies since joining Freedonia in 2005 and is currently involved in research on the polyethylene, fluoropolymer, and graphite industries and markets.

- Edward J. Holland, president and CEO of M. Holland Company. Ed Holland has spent his entire career at M. Holland Co., beginning as a sales representative in 1976 and moving up to president and CEO in 1994. During his tenure, the company has grown from a small regional plastics distributor to one of the top four distributors in North America.

- Robin Waters, director, Polyolefins North America, for IHS. Waters joined IHS in September 2012, bringing 30 years of industry experience at DuPont and Basell Polyolefins (now LyondellBasell) in roles ranging from product and sales management to strategic planning and commercial management.

Global Supply Patterns

Plastics Engineering: It’s a complex question, but overall, how have geographic polyolefin resin supply patterns changed over the last few years?

Waters: The last few years have seen significant supply buildup from the Middle East and China. The Middle East has become by far the largest exporting region for polyolefins, while China continues to look to reduce its dependence on imported resin. Over the next five years, we will see accelerated growth in the global supply of three key “building blocks”: ethylene, propylene, and methanol.

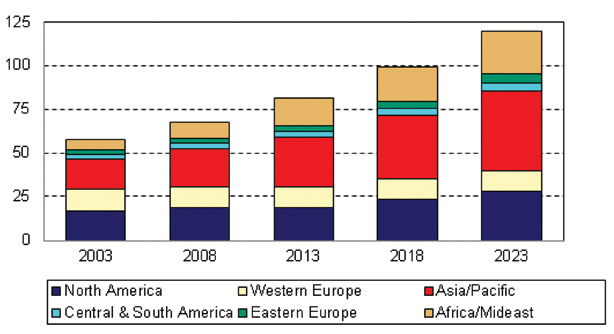

World polyethylene production by region, 2003–2023 (millions of metric tons) (chart courtesy of the The Freedonia Group, from the company’s October 2014 report, “World Polyethylene”).

The supply of these feedstocks is changing around the world. China is investing in coal- and methanol-to-olefins technologies; North America is tapping cheap domestic ethane from natural gas…. For polyethylene a key theme will be the unprecedented investments in new plants in N. America; IHS expects to see some 50% increase in PE capacity over the next five years. This significant increase in capacity will, in turn, lead N. America to become a

significant net exporter of PE. At the same time the Middle East continues to increase supply, albeit at a slower pace, while growth in China continues to outpace all regions. The continued supply growth from these three regions will lead to significant shifts in trade and also place pressure on higher-cost regions, affecting operating rates and in some cases resulting in asset rationalizations.

Polyethylene Prices: Whys & Wherefores

PE: Considering the North American production of shale gas, why have polyethylene prices not really fallen over past couple years (as of November 2014)?

Furst: The answer is pretty simple: basic supply and demand. Even though shale gas has dramatically reduced production costs for ethylene and polyethylene in N. America, new production capacity has not yet come online. So polyethylene producers have been able to maintain current prices and enjoy the increased profitability from cheap feedstocks. In fact, most producers have been able to raise polyethylene prices since operating rates have been so high.

Holland: While shale gas does deliver lower-cost feedstocks to the U.S. petrochemicals market, the infrastructure to deliver product is still being put in place. Only a limited amount of producers have been able to introduce shale gas feeds into their operations and complete their conversions. In the meantime, driven by strong demand and operational issues that have led to significant downtime, the N. American polyethylene market has been operating at very high utilization rates. Thus the current market has been more driven by supply and demand than cost. Even with the addition of new capacity starting in 2015, the global supply/demand balance will still be the main driver of polyethylene pricing. Any polymer pricing reductions solely based on capacity additions are likely to be more tempered and short term.

Bezaire: Polyethylene is a globally traded product with the price floor set by producers with high costs, not by those with low costs. While the production of shale gas provides N. American ethane-based producers with production costs that are among the lowest in the world, the ethylene and polyethylene price floor is set by high-cost naphtha-based producers globally, and so shale gas does not directly impact the price of polyethylene. In addition, based on the N. American cost advantage, producers have the ability to export into the global market, and expect to be able to continue this in the future, even as supply growth begins to outpace demand growth.

Waters: The fundamental basis for polyethylene prices remaining high is based the fact that global demand cannot be satisfied solely from low-cost regions like the Middle East and N. America but also requires supply from producers at the upper end of the production cost curve. Thus there is a global price-setting mechanism for polyethylene, an easily transportable product. Producers in lower-cost regions therefore are able to take prices essentially set by higher-cost competitors. This brings into discussion the cyclic nature of the chemical industry where high margins attract investments in what is a very capital intensive industry—a process we are seeing played out here in N. America.

Robin Waters

Lower PE Prices to Come?

PE: When will we really start to notice the effects of shale gas production on polyethylene and polypropylene prices? Or, why should we not expect to notice an effect on prices?

Bezaire: We don’t expect shale gas production or future polyethylene supply growth to (materially) affect polyethylene prices, because the price floor is set by the relatively high production costs of naphtha-based producers around the world. As an example, polyethylene prices in the Middle East are not significantly different than polyethylene prices around the world—even though their ethane-based operations have the lowest cost structure in the world.

Furst: Unfortunately, I don’t think we’ll see a dramatic decline in prices—processors will not be able to party like it’s 1999. Again, supply and demand are at work here—Freedonia’s research has found that the global market should be able to absorb all the polyethylene capacity increases that have been announced in N. America. Even though capacity growth seems excessive, declining production in Europe and flat growth in South America will provide ample export opportunities for N. American resin. So I doubt there will be the kind of overcapacity and intense competition that leads to lower prices. The more likely scenario is slower increases in polyethylene prices, below inflation.

Waters: For polyethylene prices, we could start to see the effect of shale gas as early as late 2015 as the anticipation of new capacities becomes more imminent with the completion of Braskem IDESA project in Mexico. However, it is more likely that the full effect won’t be seen until 2017/2018 time frame, as expected capacity builds in N. America result in significant exports leaving the region.

An important consideration in this development is how much capacity South America, North America’s preferred export region, will be able to absorb…. To evaluate that situation one must consider not only what if any new capacity will be built in S. America, but also what other regions, such as the Middle East, will be competing for share in the region.

IHS currently projects that N. American prices will become much more competitive compared to other regions—not the case today… and, along with more competitive energy costs overall, see improved competitiveness in the processing community, particularly for those applications that benefit from what we refer to as “supply chain intensity,” i.e., applications requiring attributes such as short lead times, high value-in-use, high service requirements, and more rigid specifications.

For polypropylene, the effect on prices differs somewhat given the nature of its feedstock supply. For certain, N. America benefits from low-cost propane, and this is driving projects for on-purpose production of propylene in N. America. The question is how much of a role will polypropylene play in monetizing the propane and propylene; IHS believe polypropylene projects will emerge, but, as the value chain is less integrated than that for ethylene and polyethylene, the capacity growth is not expected to have as dramatic effect on N. America net trade as that for polyethylene.

Chris Bezaire

For this reason IHS believes that, while N. American polypropylene prices will moderate relative to other regions, the impact will be less than that for polyethylene. That being given, polypropylene continues to grow at impressive rates due to its value in use, and we expect that trend to continue.

PE: Are there signs that commodity resin users are doing more switching between resin types because of anticipated natural gas production trends or volatility?

Ed Holland

Bezaire: We continue to see interest among some polypropylene converters in switching to polyethylene due to the perceived lower volatility in polyethylene pricing, and where polyethylene offers equivalent or even improved performance in their applications.

Oil’s Influence

PE: What about the price of oil? How might continuing low oil prices impact resin prices in 2015?

Holland: One major impact of lower oil prices is to make heavy-feedstock-derived product more competitive in the global market. A second and more unpredictable result is the geopolitical effect that lower oil prices will have on the economies and subsequent stability and policies of countries like Russia, Venezuela, Nigeria, Iraq, and others whose government budgets are only sustainable at oil prices over $80 per barrel. Unrest in these already volatile countries can have the effect of increasing global economic uncertainty and the resultant growth outlooks.

Another fallout of lower oil prices, if sustained for any period, could be a slowdown in the extraction and development of shale gas and oil in N. America. This, in turn, could give pause to the U.S. petrochemical expansions announced but as yet unbuilt.

Waters: It’s important to realize that, on a global basis, polyethylene capacity exceeds demand to the point that global operating rates average in the mid-80% range. So lower oil prices will result in lower prices, beginning with those producers whose costs are more directly associated with the higher-cost crude-based feed stocks, namely naphtha, and especially those located within large demand regions, for example China, where capacity utilization is already challenged by lower-cost exporting regions, namely the Middle East. Lower oil prices may, however, lead to marginally improved margins for local, naphtha-based producers, incentivizing them to run at higher rates.

The combination of lower costs and, perhaps higher production from producers on the upper end of the cost curve leads to increased price pressure for the producers in low-cost exporting regions to maintain full production rates, which we would expect them to do given the attractive margins that still exist despite lower crude. At some point the lower export prices needed to maintain position in export markets reach a point where domestic prices are influenced and respond; how much and when can be debated.

Kent Furst

Other Influences

PE: What are some less-often talked-about influences on resin prices that will be relevant in 2015?

Holland: The health of the overall global market, especially in the presumed high growth Chinese and Indian economies, is always an overlay to any discussion of future pricing influences. Recent stimulation of the Chinese market through the lowering of interest rates has raised concern of the ability to sustain the aggressive growth targets expected of the Chinese consumer market. The Chinese have proven predictions of their inability to sustain growth wrong in the past, but it is worthy of close attention.

Another influence in 2015 could be the strength of the U.S. dollar. If predictions of an even stronger dollar in 2015 come true, it will improve the prospects for resin and finished goods imports to N. America and negatively impact the U.S. export market. In resin markets, this has the capability to be magnified if oil prices remain at levels below $80 per barrel and heavy-feedstock-dependent international producers are able to better compete in the U.S. market.

Waters: We can’t ignore the global economy and its impact going into 2015. In 2014 we saw positive economic news regarding the USA, for example, but growing concerns regarding emerging economies, as well as continued conflicts that continue to raise concerns over sustained global growth. We need to continue to understand and anticipate the impact events in other regions have on prices here in N. America.

Of course we also need to continue to sort out the impact of any prolonged period of low crude which, if played out as many expect, will lead to shifts not really contemplated for much of the past couple of years. Of particular interest would be the impact on capital spending in N. America, which could see delays if the assumed cost advantage for natural gas vs. crude is viewed less favorably. All of these topics are intertwined and mean perhaps a more complicated picture compared to a year ago.

Bag Ban Effects?

Plastics Engineering: What could be the effects of plastics product bans, like California’s bag ban, on resin supplies and price patterns? At what point could a plastic product ban, even nationwide bans, influence resin production patterns and prices?

Furst: According to Freedonia, U.S. demand for retail plastic bags was about 1.7 billion pounds in 2013. Assuming California is 13% of U.S. demand (same as its share of GDP), the state’s bag ban would impact 230 million pounds of PE resin. That’s a lot of resin, but it’s less than 1% of the 29 billion pounds of polyethylene consumed in the USA overall, so it is unlikely to have an effect on prices.

Even a nationwide bag ban would have a limited effect. For plastic product bans to really impact resin production and prices, they would have to target a much larger portion of overall resin demand, such as PET beverage bottles or EPS foam containers, which is unlikely. However, there is certainly the threat of “death by a thousand cuts,” where numerous bans of a limited scope lead companies to voluntarily abandon a particular plastic product.

Bio-Based Resins: Priced Out?

Plastics Engineering: Are there any signs that bio-based polymer prices are becoming competitive with conventionally produced resins? If so, which bioresins and why?

Furst: Low-cost natural gas has had a significant negative effect on the biobased plastics industry. However, this has less to do with price than it does with investment, business focus, and margins. Braskem, Dow Chemical, and Mitsui have all shelved plans to build biobased polyethylene capacity in Brazil not necessarily because the economics were bad, but because their investment focus turned to gas-based polyethylene. Even if biobased polyethylene is at price parity, gas-based polyethylene is an established technology which is a sure bet in terms of profitability.

Other biobased plastics have had enormous difficultly in achieving price parity, and a number of high-profile companies have gone out of business. The most successful has been NatureWorks’ PLA, which is not only price competitive with polystyrene and PET, but has also gained wide acceptance among plastic processors and brand owners in the USA, Europe, and Asia.

Holland: With notable positive development efforts—Braskem’s production and marketing of sugarcane-derived ethanol and LDPE and Invista’s pursuit of sugar-based nylon intermediates—bio-based polymers are not as yet having a significant effect on overall business activity in the polymers market.

In order to thrive, bio-based raw materials must first become readily available at competitive prices and in large quantities. The trend to bio-based feedstocks and their resultant polymers that exhibit all the properties and recyclability of their oil- and gas-based competitors is a positive development for these products. However, it’s been proven over and over again that these resins must be cost-competitive to be successful, and, as of yet, cost parity with established feedstock derivatives has not been achieved.

Aggressive end-user efforts to adopt bio-based, sustainable products into their supply chain are needed to drive the success of those innovative producers that have committed significant capital investment to these products.

Global Resin Trends 2015: An Expert Roundtable

Previous Article Next Article

By Michael Tolinski

Given all the attention on new sources of resin feedstock (i.e., shale gas), there’s a strong need for some expert comment to put current (and future) resin trends into context. Below, four experts in the areas of polyolefin supply and demand respond to some timely questions, offering some long-range views—plus explanations about why things might not turn out as some people expect.

This year’s “Roundtable” features responses from:

- Chris Bezaire, senior vice president, Polyethylene Business, for Nova Chemicals. Bezaire joined Nova in 1994. Prior to his appointment to the management team, he served as vice president for Business and Technology Integration.

- Kent Furst, manager, Polymers & Materials Group, for The Freedonia Group, Inc. Furst has written over 50 studies since joining Freedonia in 2005 and is currently involved in research on the polyethylene, fluoropolymer, and graphite industries and markets.

- Edward J. Holland, president and CEO of M. Holland Company. Ed Holland has spent his entire career at M. Holland Co., beginning as a sales representative in 1976 and moving up to president and CEO in 1994. During his tenure, the company has grown from a small regional plastics distributor to one of the top four distributors in North America.

- Robin Waters, director, Polyolefins North America, for IHS. Waters joined IHS in September 2012, bringing 30 years of industry experience at DuPont and Basell Polyolefins (now LyondellBasell) in roles ranging from product and sales management to strategic planning and commercial management.

Global Supply Patterns

Plastics Engineering: It’s a complex question, but overall, how have geographic polyolefin resin supply patterns changed over the last few years?

Waters: The last few years have seen significant supply buildup from the Middle East and China. The Middle East has become by far the largest exporting region for polyolefins, while China continues to look to reduce its dependence on imported resin. Over the next five years, we will see accelerated growth in the global supply of three key “building blocks”: ethylene, propylene, and methanol.

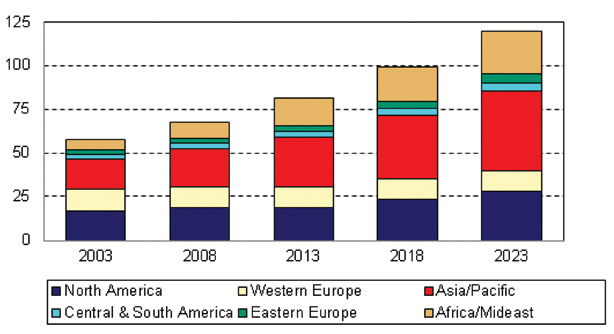

World polyethylene production by region, 2003–2023 (millions of metric tons) (chart courtesy of the The Freedonia Group, from the company’s October 2014 report, “World Polyethylene”).

The supply of these feedstocks is changing around the world. China is investing in coal- and methanol-to-olefins technologies; North America is tapping cheap domestic ethane from natural gas…. For polyethylene a key theme will be the unprecedented investments in new plants in N. America; IHS expects to see some 50% increase in PE capacity over the next five years. This significant increase in capacity will, in turn, lead N. America to become a

significant net exporter of PE. At the same time the Middle East continues to increase supply, albeit at a slower pace, while growth in China continues to outpace all regions. The continued supply growth from these three regions will lead to significant shifts in trade and also place pressure on higher-cost regions, affecting operating rates and in some cases resulting in asset rationalizations.

Polyethylene Prices: Whys & Wherefores

PE: Considering the North American production of shale gas, why have polyethylene prices not really fallen over past couple years (as of November 2014)?

Furst: The answer is pretty simple: basic supply and demand. Even though shale gas has dramatically reduced production costs for ethylene and polyethylene in N. America, new production capacity has not yet come online. So polyethylene producers have been able to maintain current prices and enjoy the increased profitability from cheap feedstocks. In fact, most producers have been able to raise polyethylene prices since operating rates have been so high.

Holland: While shale gas does deliver lower-cost feedstocks to the U.S. petrochemicals market, the infrastructure to deliver product is still being put in place. Only a limited amount of producers have been able to introduce shale gas feeds into their operations and complete their conversions. In the meantime, driven by strong demand and operational issues that have led to significant downtime, the N. American polyethylene market has been operating at very high utilization rates. Thus the current market has been more driven by supply and demand than cost. Even with the addition of new capacity starting in 2015, the global supply/demand balance will still be the main driver of polyethylene pricing. Any polymer pricing reductions solely based on capacity additions are likely to be more tempered and short term.

Bezaire: Polyethylene is a globally traded product with the price floor set by producers with high costs, not by those with low costs. While the production of shale gas provides N. American ethane-based producers with production costs that are among the lowest in the world, the ethylene and polyethylene price floor is set by high-cost naphtha-based producers globally, and so shale gas does not directly impact the price of polyethylene. In addition, based on the N. American cost advantage, producers have the ability to export into the global market, and expect to be able to continue this in the future, even as supply growth begins to outpace demand growth.

Waters: The fundamental basis for polyethylene prices remaining high is based the fact that global demand cannot be satisfied solely from low-cost regions like the Middle East and N. America but also requires supply from producers at the upper end of the production cost curve. Thus there is a global price-setting mechanism for polyethylene, an easily transportable product. Producers in lower-cost regions therefore are able to take prices essentially set by higher-cost competitors. This brings into discussion the cyclic nature of the chemical industry where high margins attract investments in what is a very capital intensive industry—a process we are seeing played out here in N. America.

Robin Waters

Lower PE Prices to Come?

PE: When will we really start to notice the effects of shale gas production on polyethylene and polypropylene prices? Or, why should we not expect to notice an effect on prices?

Bezaire: We don’t expect shale gas production or future polyethylene supply growth to (materially) affect polyethylene prices, because the price floor is set by the relatively high production costs of naphtha-based producers around the world. As an example, polyethylene prices in the Middle East are not significantly different than polyethylene prices around the world—even though their ethane-based operations have the lowest cost structure in the world.

Furst: Unfortunately, I don’t think we’ll see a dramatic decline in prices—processors will not be able to party like it’s 1999. Again, supply and demand are at work here—Freedonia’s research has found that the global market should be able to absorb all the polyethylene capacity increases that have been announced in N. America. Even though capacity growth seems excessive, declining production in Europe and flat growth in South America will provide ample export opportunities for N. American resin. So I doubt there will be the kind of overcapacity and intense competition that leads to lower prices. The more likely scenario is slower increases in polyethylene prices, below inflation.

Waters: For polyethylene prices, we could start to see the effect of shale gas as early as late 2015 as the anticipation of new capacities becomes more imminent with the completion of Braskem IDESA project in Mexico. However, it is more likely that the full effect won’t be seen until 2017/2018 time frame, as expected capacity builds in N. America result in significant exports leaving the region.

An important consideration in this development is how much capacity South America, North America’s preferred export region, will be able to absorb…. To evaluate that situation one must consider not only what if any new capacity will be built in S. America, but also what other regions, such as the Middle East, will be competing for share in the region.

IHS currently projects that N. American prices will become much more competitive compared to other regions—not the case today… and, along with more competitive energy costs overall, see improved competitiveness in the processing community, particularly for those applications that benefit from what we refer to as “supply chain intensity,” i.e., applications requiring attributes such as short lead times, high value-in-use, high service requirements, and more rigid specifications.

For polypropylene, the effect on prices differs somewhat given the nature of its feedstock supply. For certain, N. America benefits from low-cost propane, and this is driving projects for on-purpose production of propylene in N. America. The question is how much of a role will polypropylene play in monetizing the propane and propylene; IHS believe polypropylene projects will emerge, but, as the value chain is less integrated than that for ethylene and polyethylene, the capacity growth is not expected to have as dramatic effect on N. America net trade as that for polyethylene.

Chris Bezaire

For this reason IHS believes that, while N. American polypropylene prices will moderate relative to other regions, the impact will be less than that for polyethylene. That being given, polypropylene continues to grow at impressive rates due to its value in use, and we expect that trend to continue.

PE: Are there signs that commodity resin users are doing more switching between resin types because of anticipated natural gas production trends or volatility?

Ed Holland

Bezaire: We continue to see interest among some polypropylene converters in switching to polyethylene due to the perceived lower volatility in polyethylene pricing, and where polyethylene offers equivalent or even improved performance in their applications.

Oil’s Influence

PE: What about the price of oil? How might continuing low oil prices impact resin prices in 2015?

Holland: One major impact of lower oil prices is to make heavy-feedstock-derived product more competitive in the global market. A second and more unpredictable result is the geopolitical effect that lower oil prices will have on the economies and subsequent stability and policies of countries like Russia, Venezuela, Nigeria, Iraq, and others whose government budgets are only sustainable at oil prices over $80 per barrel. Unrest in these already volatile countries can have the effect of increasing global economic uncertainty and the resultant growth outlooks.

Another fallout of lower oil prices, if sustained for any period, could be a slowdown in the extraction and development of shale gas and oil in N. America. This, in turn, could give pause to the U.S. petrochemical expansions announced but as yet unbuilt.

Waters: It’s important to realize that, on a global basis, polyethylene capacity exceeds demand to the point that global operating rates average in the mid-80% range. So lower oil prices will result in lower prices, beginning with those producers whose costs are more directly associated with the higher-cost crude-based feed stocks, namely naphtha, and especially those located within large demand regions, for example China, where capacity utilization is already challenged by lower-cost exporting regions, namely the Middle East. Lower oil prices may, however, lead to marginally improved margins for local, naphtha-based producers, incentivizing them to run at higher rates.

The combination of lower costs and, perhaps higher production from producers on the upper end of the cost curve leads to increased price pressure for the producers in low-cost exporting regions to maintain full production rates, which we would expect them to do given the attractive margins that still exist despite lower crude. At some point the lower export prices needed to maintain position in export markets reach a point where domestic prices are influenced and respond; how much and when can be debated.

Kent Furst

Other Influences

PE: What are some less-often talked-about influences on resin prices that will be relevant in 2015?

Holland: The health of the overall global market, especially in the presumed high growth Chinese and Indian economies, is always an overlay to any discussion of future pricing influences. Recent stimulation of the Chinese market through the lowering of interest rates has raised concern of the ability to sustain the aggressive growth targets expected of the Chinese consumer market. The Chinese have proven predictions of their inability to sustain growth wrong in the past, but it is worthy of close attention.

Another influence in 2015 could be the strength of the U.S. dollar. If predictions of an even stronger dollar in 2015 come true, it will improve the prospects for resin and finished goods imports to N. America and negatively impact the U.S. export market. In resin markets, this has the capability to be magnified if oil prices remain at levels below $80 per barrel and heavy-feedstock-dependent international producers are able to better compete in the U.S. market.

Waters: We can’t ignore the global economy and its impact going into 2015. In 2014 we saw positive economic news regarding the USA, for example, but growing concerns regarding emerging economies, as well as continued conflicts that continue to raise concerns over sustained global growth. We need to continue to understand and anticipate the impact events in other regions have on prices here in N. America.

Of course we also need to continue to sort out the impact of any prolonged period of low crude which, if played out as many expect, will lead to shifts not really contemplated for much of the past couple of years. Of particular interest would be the impact on capital spending in N. America, which could see delays if the assumed cost advantage for natural gas vs. crude is viewed less favorably. All of these topics are intertwined and mean perhaps a more complicated picture compared to a year ago.

Bag Ban Effects?

Plastics Engineering: What could be the effects of plastics product bans, like California’s bag ban, on resin supplies and price patterns? At what point could a plastic product ban, even nationwide bans, influence resin production patterns and prices?

Furst: According to Freedonia, U.S. demand for retail plastic bags was about 1.7 billion pounds in 2013. Assuming California is 13% of U.S. demand (same as its share of GDP), the state’s bag ban would impact 230 million pounds of PE resin. That’s a lot of resin, but it’s less than 1% of the 29 billion pounds of polyethylene consumed in the USA overall, so it is unlikely to have an effect on prices.

Even a nationwide bag ban would have a limited effect. For plastic product bans to really impact resin production and prices, they would have to target a much larger portion of overall resin demand, such as PET beverage bottles or EPS foam containers, which is unlikely. However, there is certainly the threat of “death by a thousand cuts,” where numerous bans of a limited scope lead companies to voluntarily abandon a particular plastic product.

Bio-Based Resins: Priced Out?

Plastics Engineering: Are there any signs that bio-based polymer prices are becoming competitive with conventionally produced resins? If so, which bioresins and why?

Furst: Low-cost natural gas has had a significant negative effect on the biobased plastics industry. However, this has less to do with price than it does with investment, business focus, and margins. Braskem, Dow Chemical, and Mitsui have all shelved plans to build biobased polyethylene capacity in Brazil not necessarily because the economics were bad, but because their investment focus turned to gas-based polyethylene. Even if biobased polyethylene is at price parity, gas-based polyethylene is an established technology which is a sure bet in terms of profitability.

Other biobased plastics have had enormous difficultly in achieving price parity, and a number of high-profile companies have gone out of business. The most successful has been NatureWorks’ PLA, which is not only price competitive with polystyrene and PET, but has also gained wide acceptance among plastic processors and brand owners in the USA, Europe, and Asia.

Holland: With notable positive development efforts—Braskem’s production and marketing of sugarcane-derived ethanol and LDPE and Invista’s pursuit of sugar-based nylon intermediates—bio-based polymers are not as yet having a significant effect on overall business activity in the polymers market.

In order to thrive, bio-based raw materials must first become readily available at competitive prices and in large quantities. The trend to bio-based feedstocks and their resultant polymers that exhibit all the properties and recyclability of their oil- and gas-based competitors is a positive development for these products. However, it’s been proven over and over again that these resins must be cost-competitive to be successful, and, as of yet, cost parity with established feedstock derivatives has not been achieved.

Aggressive end-user efforts to adopt bio-based, sustainable products into their supply chain are needed to drive the success of those innovative producers that have committed significant capital investment to these products.

Global Resin Trends 2015: An Expert Roundtable

Previous Article Next Article

By Michael Tolinski

Given all the attention on new sources of resin feedstock (i.e., shale gas), there’s a strong need for some expert comment to put current (and future) resin trends into context. Below, four experts in the areas of polyolefin supply and demand respond to some timely questions, offering some long-range views—plus explanations about why things might not turn out as some people expect.

This year’s “Roundtable” features responses from:

- Chris Bezaire, senior vice president, Polyethylene Business, for Nova Chemicals. Bezaire joined Nova in 1994. Prior to his appointment to the management team, he served as vice president for Business and Technology Integration.

- Kent Furst, manager, Polymers & Materials Group, for The Freedonia Group, Inc. Furst has written over 50 studies since joining Freedonia in 2005 and is currently involved in research on the polyethylene, fluoropolymer, and graphite industries and markets.

- Edward J. Holland, president and CEO of M. Holland Company. Ed Holland has spent his entire career at M. Holland Co., beginning as a sales representative in 1976 and moving up to president and CEO in 1994. During his tenure, the company has grown from a small regional plastics distributor to one of the top four distributors in North America.

- Robin Waters, director, Polyolefins North America, for IHS. Waters joined IHS in September 2012, bringing 30 years of industry experience at DuPont and Basell Polyolefins (now LyondellBasell) in roles ranging from product and sales management to strategic planning and commercial management.

Global Supply Patterns

Plastics Engineering: It’s a complex question, but overall, how have geographic polyolefin resin supply patterns changed over the last few years?

Waters: The last few years have seen significant supply buildup from the Middle East and China. The Middle East has become by far the largest exporting region for polyolefins, while China continues to look to reduce its dependence on imported resin. Over the next five years, we will see accelerated growth in the global supply of three key “building blocks”: ethylene, propylene, and methanol.

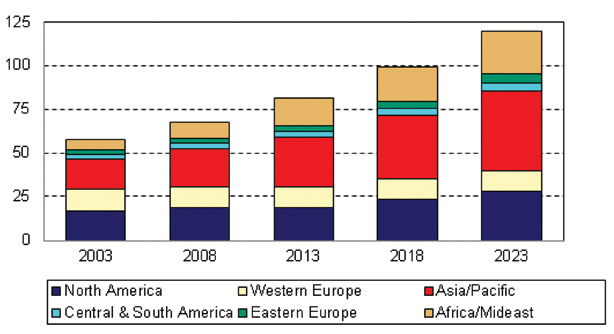

World polyethylene production by region, 2003–2023 (millions of metric tons) (chart courtesy of the The Freedonia Group, from the company’s October 2014 report, “World Polyethylene”).

The supply of these feedstocks is changing around the world. China is investing in coal- and methanol-to-olefins technologies; North America is tapping cheap domestic ethane from natural gas…. For polyethylene a key theme will be the unprecedented investments in new plants in N. America; IHS expects to see some 50% increase in PE capacity over the next five years. This significant increase in capacity will, in turn, lead N. America to become a

significant net exporter of PE. At the same time the Middle East continues to increase supply, albeit at a slower pace, while growth in China continues to outpace all regions. The continued supply growth from these three regions will lead to significant shifts in trade and also place pressure on higher-cost regions, affecting operating rates and in some cases resulting in asset rationalizations.

Polyethylene Prices: Whys & Wherefores

PE: Considering the North American production of shale gas, why have polyethylene prices not really fallen over past couple years (as of November 2014)?

Furst: The answer is pretty simple: basic supply and demand. Even though shale gas has dramatically reduced production costs for ethylene and polyethylene in N. America, new production capacity has not yet come online. So polyethylene producers have been able to maintain current prices and enjoy the increased profitability from cheap feedstocks. In fact, most producers have been able to raise polyethylene prices since operating rates have been so high.

Holland: While shale gas does deliver lower-cost feedstocks to the U.S. petrochemicals market, the infrastructure to deliver product is still being put in place. Only a limited amount of producers have been able to introduce shale gas feeds into their operations and complete their conversions. In the meantime, driven by strong demand and operational issues that have led to significant downtime, the N. American polyethylene market has been operating at very high utilization rates. Thus the current market has been more driven by supply and demand than cost. Even with the addition of new capacity starting in 2015, the global supply/demand balance will still be the main driver of polyethylene pricing. Any polymer pricing reductions solely based on capacity additions are likely to be more tempered and short term.

Bezaire: Polyethylene is a globally traded product with the price floor set by producers with high costs, not by those with low costs. While the production of shale gas provides N. American ethane-based producers with production costs that are among the lowest in the world, the ethylene and polyethylene price floor is set by high-cost naphtha-based producers globally, and so shale gas does not directly impact the price of polyethylene. In addition, based on the N. American cost advantage, producers have the ability to export into the global market, and expect to be able to continue this in the future, even as supply growth begins to outpace demand growth.

Waters: The fundamental basis for polyethylene prices remaining high is based the fact that global demand cannot be satisfied solely from low-cost regions like the Middle East and N. America but also requires supply from producers at the upper end of the production cost curve. Thus there is a global price-setting mechanism for polyethylene, an easily transportable product. Producers in lower-cost regions therefore are able to take prices essentially set by higher-cost competitors. This brings into discussion the cyclic nature of the chemical industry where high margins attract investments in what is a very capital intensive industry—a process we are seeing played out here in N. America.

Robin Waters

Lower PE Prices to Come?

PE: When will we really start to notice the effects of shale gas production on polyethylene and polypropylene prices? Or, why should we not expect to notice an effect on prices?

Bezaire: We don’t expect shale gas production or future polyethylene supply growth to (materially) affect polyethylene prices, because the price floor is set by the relatively high production costs of naphtha-based producers around the world. As an example, polyethylene prices in the Middle East are not significantly different than polyethylene prices around the world—even though their ethane-based operations have the lowest cost structure in the world.

Furst: Unfortunately, I don’t think we’ll see a dramatic decline in prices—processors will not be able to party like it’s 1999. Again, supply and demand are at work here—Freedonia’s research has found that the global market should be able to absorb all the polyethylene capacity increases that have been announced in N. America. Even though capacity growth seems excessive, declining production in Europe and flat growth in South America will provide ample export opportunities for N. American resin. So I doubt there will be the kind of overcapacity and intense competition that leads to lower prices. The more likely scenario is slower increases in polyethylene prices, below inflation.

Waters: For polyethylene prices, we could start to see the effect of shale gas as early as late 2015 as the anticipation of new capacities becomes more imminent with the completion of Braskem IDESA project in Mexico. However, it is more likely that the full effect won’t be seen until 2017/2018 time frame, as expected capacity builds in N. America result in significant exports leaving the region.

An important consideration in this development is how much capacity South America, North America’s preferred export region, will be able to absorb…. To evaluate that situation one must consider not only what if any new capacity will be built in S. America, but also what other regions, such as the Middle East, will be competing for share in the region.

IHS currently projects that N. American prices will become much more competitive compared to other regions—not the case today… and, along with more competitive energy costs overall, see improved competitiveness in the processing community, particularly for those applications that benefit from what we refer to as “supply chain intensity,” i.e., applications requiring attributes such as short lead times, high value-in-use, high service requirements, and more rigid specifications.

For polypropylene, the effect on prices differs somewhat given the nature of its feedstock supply. For certain, N. America benefits from low-cost propane, and this is driving projects for on-purpose production of propylene in N. America. The question is how much of a role will polypropylene play in monetizing the propane and propylene; IHS believe polypropylene projects will emerge, but, as the value chain is less integrated than that for ethylene and polyethylene, the capacity growth is not expected to have as dramatic effect on N. America net trade as that for polyethylene.

Chris Bezaire

For this reason IHS believes that, while N. American polypropylene prices will moderate relative to other regions, the impact will be less than that for polyethylene. That being given, polypropylene continues to grow at impressive rates due to its value in use, and we expect that trend to continue.

PE: Are there signs that commodity resin users are doing more switching between resin types because of anticipated natural gas production trends or volatility?

Ed Holland

Bezaire: We continue to see interest among some polypropylene converters in switching to polyethylene due to the perceived lower volatility in polyethylene pricing, and where polyethylene offers equivalent or even improved performance in their applications.

Oil’s Influence

PE: What about the price of oil? How might continuing low oil prices impact resin prices in 2015?

Holland: One major impact of lower oil prices is to make heavy-feedstock-derived product more competitive in the global market. A second and more unpredictable result is the geopolitical effect that lower oil prices will have on the economies and subsequent stability and policies of countries like Russia, Venezuela, Nigeria, Iraq, and others whose government budgets are only sustainable at oil prices over $80 per barrel. Unrest in these already volatile countries can have the effect of increasing global economic uncertainty and the resultant growth outlooks.

Another fallout of lower oil prices, if sustained for any period, could be a slowdown in the extraction and development of shale gas and oil in N. America. This, in turn, could give pause to the U.S. petrochemical expansions announced but as yet unbuilt.

Waters: It’s important to realize that, on a global basis, polyethylene capacity exceeds demand to the point that global operating rates average in the mid-80% range. So lower oil prices will result in lower prices, beginning with those producers whose costs are more directly associated with the higher-cost crude-based feed stocks, namely naphtha, and especially those located within large demand regions, for example China, where capacity utilization is already challenged by lower-cost exporting regions, namely the Middle East. Lower oil prices may, however, lead to marginally improved margins for local, naphtha-based producers, incentivizing them to run at higher rates.

The combination of lower costs and, perhaps higher production from producers on the upper end of the cost curve leads to increased price pressure for the producers in low-cost exporting regions to maintain full production rates, which we would expect them to do given the attractive margins that still exist despite lower crude. At some point the lower export prices needed to maintain position in export markets reach a point where domestic prices are influenced and respond; how much and when can be debated.

Kent Furst

Other Influences

PE: What are some less-often talked-about influences on resin prices that will be relevant in 2015?

Holland: The health of the overall global market, especially in the presumed high growth Chinese and Indian economies, is always an overlay to any discussion of future pricing influences. Recent stimulation of the Chinese market through the lowering of interest rates has raised concern of the ability to sustain the aggressive growth targets expected of the Chinese consumer market. The Chinese have proven predictions of their inability to sustain growth wrong in the past, but it is worthy of close attention.

Another influence in 2015 could be the strength of the U.S. dollar. If predictions of an even stronger dollar in 2015 come true, it will improve the prospects for resin and finished goods imports to N. America and negatively impact the U.S. export market. In resin markets, this has the capability to be magnified if oil prices remain at levels below $80 per barrel and heavy-feedstock-dependent international producers are able to better compete in the U.S. market.

Waters: We can’t ignore the global economy and its impact going into 2015. In 2014 we saw positive economic news regarding the USA, for example, but growing concerns regarding emerging economies, as well as continued conflicts that continue to raise concerns over sustained global growth. We need to continue to understand and anticipate the impact events in other regions have on prices here in N. America.

Of course we also need to continue to sort out the impact of any prolonged period of low crude which, if played out as many expect, will lead to shifts not really contemplated for much of the past couple of years. Of particular interest would be the impact on capital spending in N. America, which could see delays if the assumed cost advantage for natural gas vs. crude is viewed less favorably. All of these topics are intertwined and mean perhaps a more complicated picture compared to a year ago.

Bag Ban Effects?

Plastics Engineering: What could be the effects of plastics product bans, like California’s bag ban, on resin supplies and price patterns? At what point could a plastic product ban, even nationwide bans, influence resin production patterns and prices?

Furst: According to Freedonia, U.S. demand for retail plastic bags was about 1.7 billion pounds in 2013. Assuming California is 13% of U.S. demand (same as its share of GDP), the state’s bag ban would impact 230 million pounds of PE resin. That’s a lot of resin, but it’s less than 1% of the 29 billion pounds of polyethylene consumed in the USA overall, so it is unlikely to have an effect on prices.

Even a nationwide bag ban would have a limited effect. For plastic product bans to really impact resin production and prices, they would have to target a much larger portion of overall resin demand, such as PET beverage bottles or EPS foam containers, which is unlikely. However, there is certainly the threat of “death by a thousand cuts,” where numerous bans of a limited scope lead companies to voluntarily abandon a particular plastic product.

Bio-Based Resins: Priced Out?

Plastics Engineering: Are there any signs that bio-based polymer prices are becoming competitive with conventionally produced resins? If so, which bioresins and why?

Furst: Low-cost natural gas has had a significant negative effect on the biobased plastics industry. However, this has less to do with price than it does with investment, business focus, and margins. Braskem, Dow Chemical, and Mitsui have all shelved plans to build biobased polyethylene capacity in Brazil not necessarily because the economics were bad, but because their investment focus turned to gas-based polyethylene. Even if biobased polyethylene is at price parity, gas-based polyethylene is an established technology which is a sure bet in terms of profitability.

Other biobased plastics have had enormous difficultly in achieving price parity, and a number of high-profile companies have gone out of business. The most successful has been NatureWorks’ PLA, which is not only price competitive with polystyrene and PET, but has also gained wide acceptance among plastic processors and brand owners in the USA, Europe, and Asia.

Holland: With notable positive development efforts—Braskem’s production and marketing of sugarcane-derived ethanol and LDPE and Invista’s pursuit of sugar-based nylon intermediates—bio-based polymers are not as yet having a significant effect on overall business activity in the polymers market.

In order to thrive, bio-based raw materials must first become readily available at competitive prices and in large quantities. The trend to bio-based feedstocks and their resultant polymers that exhibit all the properties and recyclability of their oil- and gas-based competitors is a positive development for these products. However, it’s been proven over and over again that these resins must be cost-competitive to be successful, and, as of yet, cost parity with established feedstock derivatives has not been achieved.

Aggressive end-user efforts to adopt bio-based, sustainable products into their supply chain are needed to drive the success of those innovative producers that have committed significant capital investment to these products.