A Look at Plastic Film Recycling

It’s growing, with lots of opportunity for future growth

Previous Article Next Article

By American Chemistry Council

A Look at Plastic Film Recycling

It’s growing, with lots of opportunity for future growth

Previous Article Next Article

By American Chemistry Council

A Look at Plastic Film Recycling

It’s growing, with lots of opportunity for future growth

Previous Article Next Article

By American Chemistry Council

Note:

This article continues the series of updates in PE from Plastics Make it Possible®, an initiative sponsored by America’s Plastics Makers™ through the American Chemistry Council.

In 1996, the American Plastics Council (the predecessor to today’s Plastics Division of the American Chemistry Council) commissioned a whitepaper on plastic film. In its paper,1 the environmental consulting firm Headley Pratt noted that, compared to alternatives, commonly used plastic film typically:

- uses much less material to package products;

- takes less energy to produce;

- takes up less space in shipment, storage, and at retail; and

- reduces environmental impacts of transportation.

These benefits, due primarily to plastic film’s high strength-to-weight ratio, were not really news to manufacturers of plastic film and their customers. What was newsy back then was the whitepaper’s overview of the nascent efforts to establish plastic film recycling programs, which at the time took place predominately at businesses that used large amounts of stretch wrap. Companies such as warehouse and distribution centers, bulk mail facilities, and grocery store chains had begun gathering large amounts of film over time and backhauling it to recycling facilities.

Early Collection Efforts

In all, approximately 190 million pounds (86 million kg) of film were recycled in 1995 out of a production of 11.25 billion pounds (5.1 billion kg), according to the R.W. Beck consulting firm. That added up to a 3% recycling rate. Consumer participation in the recycling of plastic film was in even earlier stages than commercial recycling. Due to the flexible nature of plastic bags and wraps, plastic film products typically were not being included in the rapidly growing plastics curbside collection programs. That remains the case today.

The supermarket chain Giant and the (then) Mobil Chemical Company initiated some of the original efforts to engage consumers in plastic film recycling. In the early 1990s, Giant placed collection bins at its 75 stores in the USA throughout Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia with signs urging consumers to return only grocery bags that were provided by Giant. The bags were back-hauled to Giant’s distribution center where they were baled and trucked to the Trex recycling facility in Winchester, Virginia. Trex (at the time owned by Mobil) used the grocery bags along with used stretch wrap to manufacture plastic lumber, which the company continues to do today.

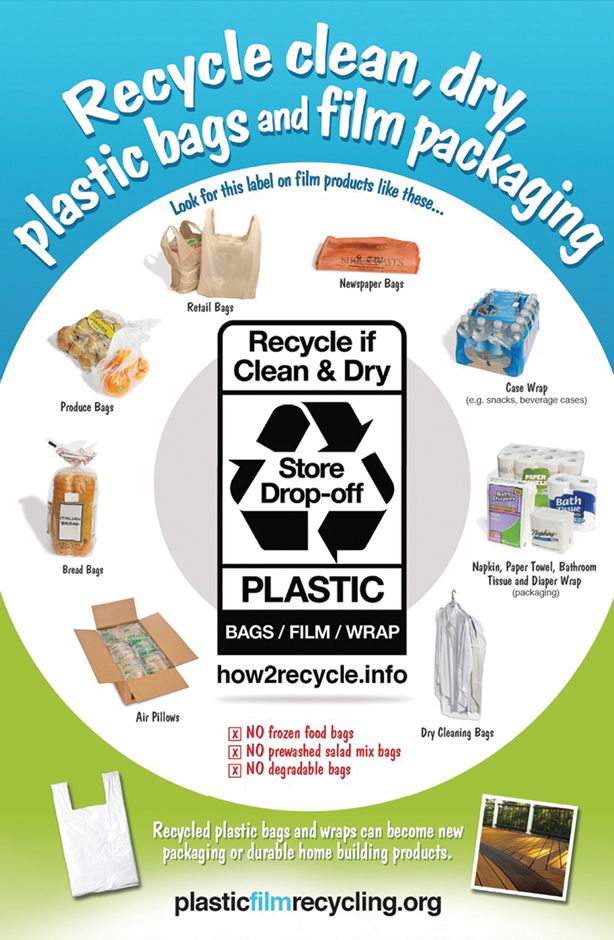

The Giant program and similar programs proved successful, and this new retail collection system for consumer grocery bags has expanded over time into a widespread collection program at thousands of major retailers across the country, including grocery stores, Target, Wal-Mart, Lowe’s, and others. The program also evolved to collect many other types of consumer film, including bread bags, newspaper bags, dry-cleaning wraps, Tyvek®, and flexible product wraps, such as wraps for cases of bottled water.

Collection Efforts Today

Today, there are more than 18,000 store drop-off locations throughout the USA that collect plastic bags, wraps, and film for recycling. As a result of this expanded collection program and increased commercial recycling, more than one billion pounds (450 million kg) of plastic film were recycled in 2012, according to Moore Recycling Associates—a more than five-fold increase since 1995. The EPA estimates that plastic film was recycled at a nearly 15% rate in 2012, the most recent year for which the agency has figures.

Interestingly, based on audits of the plastic film bales by Moore Recycling, a majority of film collected for recycling is not from grocery bags, but rather from product wraps and other film packaging.

The authors of the 1996 paper pointed out many difficulties associated with plastic film recycling, including: amassing enough volume, storage space, collection infrastructure, contamination, and moisture. While those obstacles remain, many have been overcome over the years through trial and error and pilot projects that enhance recycling efficiencies.

One important obstacle remains: consumer awareness of and participation in the recycling of plastic film. A 2014 survey by Plastics Make it Possible® found that while nearly two-thirds of Americans say they recycle on a “regular basis,” only 32% say they have returned plastic shopping bags to stores for recycling.

A recently developed labeling program for packaging could help raise awareness and jumpstart the recycling of plastic film, as well as other packaging. GreenBlue’s Sustainable Packaging Coalition in 2012 launched the “How2Recycle” label program that provides clear, simple, and nationally harmonized directions for what and where to recycle—right on the package. For the first time, this label literally puts recycling instructions into the hands of consumers, right at the point of disposal. For plastic film packaging, the label informs consumers that clean and dry bags, film, and wraps should be taken to store drop-offs for recycling.

GreenBlue’s goal is to place the How2Recycle label on the majority of consumer goods by 2016. Many big names are on board including McDonald’s USA, ConAgra, Kellogg’s, Costco, General Mills, Microsoft, and Estee Lauder.

Some recent additions to the labeling program could help boost plastic film recycling:

- Reynolds Consumer Products will print the label primarily on its Hefty brand slider bags.

- Kimberly-Clark will add the label to its Scott Naturals Tube-Free bath tissue flexible film packaging, followed by other Scott Naturals packaging and Kimberly-Clark products.

- Hilex Poly, the nation’s largest plastic bag manufacturer, will use the label on a variety of its flexible plastic packaging, including its well-known “Thank You” plastic bag.

- And Wegmans became How2Recycle’s first grocery retailer, putting the label and a “Return to Sender” message on all plastic grocery and produce bags.

Even though plastic film recycling is growing, substantial increases in consumer and commercial recycling will be needed to reach the higher recycling rates of plastic containers and other materials. Indeed, as the Plastics Division of the American Chemistry Council noted earlier this year, “[E]xisting infrastructures for collecting commercial film can be greatly expanded to capture significantly more of this material from the increasing number of businesses seeking recovery options for shrink film and transport packaging” (emphasis added).

So opportunities exist for both consumers and businesses to increase plastic film recycling. Hopefully both will take advantage of these opportunities.

For more information on plastic film recycling, visit www.plasticfilmrecycling.org.

Reference

Plastics Make it Possible highlights the many ways plastics inspire innovations that improve our lives, solve big problems, and help us design a safer, more promising future. For more information visit plasticsmakeitpossble.org.

So what happens to that billion pounds of plastic film after it has been collected? Recycled polyethylene film is used to make a range of products, such as durable plastic and composite lumber for outdoor decks and fencing, home building products, garden products, crates, pipe, new film packaging, and plastic bags. One example: Trex uses 140,000 recycled plastic bags to make 500 square feet (46.5 m2) of decking—the company is one of the largest plastic film recyclers in the USA.