The Emerging Role of Social Media in Urology

Michael J. Leveridge, MD, FRCSC

Department of Urology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

Social media have become so integrated into modern communications as to be universal in our personal and, increasingly, professional lives. Recent examples of social media uptake in urology, and the emergence of data to quantify it, reveal the expansion of conventional communication routes beyond the in-person forum. In every domain of urologic practice, from patient interaction through research to continuing professional development, the move online has unlocked another layer of conversation, dissemination, and, indeed, caveats. Social media have a democratizing effect, placing patients, trainees, practitioners, and thought leaders in the same arena and on equal footing. If uptake of social media in medicine even remotely parallels its rise to ubiquity in other areas, it will only expand and evolve in the coming years. For these reasons, this article presents an overview of the most recent data on the impact and potential complications of social media usage in the urologic community.

[Rev Urol. 2014;16(3):110-117 doi: 10.3909/riu0640]

© 2014 MedReviews®, LLC

The Emerging Role of Social Media in Urology

Michael J. Leveridge, MD, FRCSC

Department of Urology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

Social media have become so integrated into modern communications as to be universal in our personal and, increasingly, professional lives. Recent examples of social media uptake in urology, and the emergence of data to quantify it, reveal the expansion of conventional communication routes beyond the in-person forum. In every domain of urologic practice, from patient interaction through research to continuing professional development, the move online has unlocked another layer of conversation, dissemination, and, indeed, caveats. Social media have a democratizing effect, placing patients, trainees, practitioners, and thought leaders in the same arena and on equal footing. If uptake of social media in medicine even remotely parallels its rise to ubiquity in other areas, it will only expand and evolve in the coming years. For these reasons, this article presents an overview of the most recent data on the impact and potential complications of social media usage in the urologic community.

[Rev Urol. 2014;16(3):110-117 doi: 10.3909/riu0640]

© 2014 MedReviews®, LLC

The Emerging Role of Social Media in Urology

Michael J. Leveridge, MD, FRCSC

Department of Urology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

Social media have become so integrated into modern communications as to be universal in our personal and, increasingly, professional lives. Recent examples of social media uptake in urology, and the emergence of data to quantify it, reveal the expansion of conventional communication routes beyond the in-person forum. In every domain of urologic practice, from patient interaction through research to continuing professional development, the move online has unlocked another layer of conversation, dissemination, and, indeed, caveats. Social media have a democratizing effect, placing patients, trainees, practitioners, and thought leaders in the same arena and on equal footing. If uptake of social media in medicine even remotely parallels its rise to ubiquity in other areas, it will only expand and evolve in the coming years. For these reasons, this article presents an overview of the most recent data on the impact and potential complications of social media usage in the urologic community.

[Rev Urol. 2014;16(3):110-117 doi: 10.3909/riu0640]

© 2014 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Social media • Urologic practice • Education • Continuing professional development • Research publication and impact

Key words

Prostate cancer • Proton beam therapy • External beam radiation therapy • Intensity modulated radiation therapy

Journal clubs have emerged with international participation, and the use of Twitter at medical meetings has added a conversational element and dissemination potential that had not previously existed.

Typically, published responses to a manuscript may appear several months after initial publication; social media allows for discussion and critique almost instantly, either in the small scale of individual posts or in online journal clubs.

Professionalism concerns and patient boundary issues have remained front-of-mind in counterarguments against the proliferation of social media in professional practice.

Main Points

• The utilization of social media by physicians has increased greatly in recent years, as sites such as Facebook and Twitter become more and more mainstream.

• The dissemination of research findings, although still typically in print format, is also shifting to an electronic format in several forums, such as online journal clubs, Twitter conversations (through specific hashtags), and online patient communities for various ailments or concerns.

• Twitter has emerged as the most prominent distillate of social media in urology, as surveys and other tracking systems have shown that the use of meeting-specific hashtags has grown in popularity over the years at major conferences such as the American Urological Association Annual Meeting.

• The shift from print to online media has impacted the ways in which the medical community may track the impact of the scientific literature; instead of relying strictly upon number of citations for impact factor, now there are several other ways, such as number of tweets, blog posts, article pageviews, and downloads, that can indicate the popularity and greater impact of a particular report in the literature.

• As with all social media interactions, there are risks and caveats that must be considered, such as professionalism and privacy concerns. Although there are positive and convenient aspects of social media use in medical practice, proper care must be taken when offering advice and/or personal information in a public setting. For this reason, guidelines have been devised by clinicians from the British Journal of Urology International and the European Association of Urology, recommending ways to use social media responsibly.

Main Points

• The utilization of social media by physicians has increased greatly in recent years, as sites such as Facebook and Twitter become more and more mainstream.

• The dissemination of research findings, although still typically in print format, is also shifting to an electronic format in several forums, such as online journal clubs, Twitter conversations (through specific hashtags), and online patient communities for various ailments or concerns.

• Twitter has emerged as the most prominent distillate of social media in urology, as surveys and other tracking systems have shown that the use of meeting-specific hashtags has grown in popularity over the years at major conferences such as the American Urological Association Annual Meeting.

• The shift from print to online media has impacted the ways in which the medical community may track the impact of the scientific literature; instead of relying strictly upon number of citations for impact factor, now there are several other ways, such as number of tweets, blog posts, article pageviews, and downloads, that can indicate the popularity and greater impact of a particular report in the literature.

• As with all social media interactions, there are risks and caveats that must be considered, such as professionalism and privacy concerns. Although there are positive and convenient aspects of social media use in medical practice, proper care must be taken when offering advice and/or personal information in a public setting. For this reason, guidelines have been devised by clinicians from the British Journal of Urology International and the European Association of Urology, recommending ways to use social media responsibly.

Interprofessional communication and continuing professional development of and by physicians have typically involved face-to face and in-person interaction, in meeting rooms or lecture halls. Dissemination of research findings has occurred through publication in print (and, more recently, online) journals, sifting through the editorial process and with limited potential for interaction; replies and queries regarding a study typically appear months after its initial publication. Citation in subsequent research papers is the foundation of measurement of a journal’s impact.

Social media may be broadly defined as those Internet-based sites and services that are primarily conversational in nature. Users post information or opinion, and other users, either through curated access lists or public profiles, are able to comment on or share the original post. The standard bearers in the last several years have been services such as Facebook, boasting over 1 billion active users, and Twitter, with well over 200 million active users.1,2 Despite having, in large part, existed for less than a decade, these and many other services have become ubiquitous in personal and public life. In professional settings, however, uptake has been relatively guarded.3,4 Recent examples of social media uptake in urology, and the emergence of data to support it, reveal the expansion of conventional communication routes beyond the in-person forum. Journal clubs have emerged with international participation, and the use of Twitter at medical meetings has added a conversational element and dissemination potential that had not previously existed. Publication of research and measurement of its impact are also in evolution, with potential for rapid propagation of research findings and impact metrics at the article level. Concerns have emerged in step with these innovations, such as consternation about patient (and physician) privacy and boundaries, as well as risks of posting words or images that may be, or are perceived to be, unprofessional.

Attitudes Toward and Uptake of Social Media in Urology

Given the voluntary nature of subscription to social media services, the selective disclosure of demographic data at sign-up, and the application of privacy controls, very few rigorous data can be compiled regarding the adoption and use of social media by urologists. A survey of all Canadian urologists with a 45% response rate via the Internet and surface mail revealed that 26% routinely used social media services in their personal lives, but only 8% participated routinely in a professional context.4 Among frequent social media users, 76% held a Facebook account, and 41% had a Twitter account. Younger urologists had a higher uptake of personal social media use, but there was no significant difference in professional use (P = .14) between those in practice less than 10 years and those working over 20 years. Most of those surveyed admitted to passive consumption of content rather than regular active posting. They felt that the use of social media as a passive repository of educational information or for interprofessional discussion was acceptable (59% and 67%, respectively), but only 14% believed that there was any role for patient interaction online. Among the 382 respondents to a survey of American Urological Association (AUA) members by Loeb and colleagues, 74% had a social media account, although 28% endorsed use in a professional setting.3 Ninety-three percent used Facebook, and 36% had a Twitter account; similar to the Canadian data, a larger proportion of younger users (83% of those < 40 years vs 56% ≥ 40 years) were social media users and consumers. Disparities between these two surveys may reflect a rise in uptake over the months between them, or to acquisition bias from Web- and mail data collection in the first instance versus Web-only in the latter. In either case, these data reflect a relatively small and youth-skewed adoption of professional social media use as of early 2013. These data are congruent with a recent Canadian Medical Association user survey showing 45% Facebook and 10% Twitter use in the personal setting, and 0.3% and 4.0% professional use, respectively.5 A survey of practicing oncologists revealed 24% daily professional social media use.6 This survey explored the factors that promoted use of social media platforms and found that ease of use and perceived usefulness were the strongest predictors of adoption, irrespective of age.

von Muhlen and Ohno-Machado systematically reviewed manuscripts surrounding physician social media uptake.7 They found a wealth of papers that served as introductions to social media for readers, often with a tally of benefits and a rallying cry for adoption. Those studies incorporating professional use specifically stated 9% to 28% use. Meta-analysis of specific social media uptake surveys was impossible due to methodologic heterogeneity between the studies. These results hint at the need for standardization of terminology and methodology in this emerging field of study, and suggest that urologists do not deviate far from other physicians in their uptake of social media use.

Social Media in Urology Training

Social media adoption has been exceptionally high among young people, who comprise the majority of medical students, and postgraduate urology trainees. The use of these tools by such “digital natives” is approached in a different way than for those who did not grow up with social media in their lives, and, as such, attitudes toward the appropriateness of posts and exposure to professional risks may be expected to be different than older users.8 von Muhlen and Ohno-Machado’s 2012 review of social media adoption publications in the medical literature featured several assessments of student uptake.7 Student use of personal accounts was 64% to 96%, published in years when social media did not enjoy the cultural ubiquity they currently experience. A recent single-institution survey revealed that 99% of first- and second-year medical students used social media services daily.9 Half of medical students surveyed by Garner and O’Sullivan admitted to having “embarrassing” photos of themselves on Facebook.10 Wikipedia was a common professionally used resource, with 70% weekly use as a direct medical reference.

Researchers surveyed 110 Canadian urology residents regarding their social media habits and attitudes.11 Whereas 65% of the 67 (61%) respondents used social media daily in their personal lives, only 3% acknowledged daily use in a professional setting. Two-thirds (66%) felt that social media in the medical setting was best suited to discussion forums between physicians. Only 4% of residents were aware of medical society or institutional guidelines addressing the use of social media, and 85% felt that their online activity could put them at risk if it was perceived to be unprofessional. The AUA survey by Loeb and colleagues3 included responses from 147 residents or clinical fellows. Eighty-six percent had a social media presence (98% of those have a Facebook account, and 35% are on Twitter). Only 20% acknowledged any business use of social media. Anecdotally, several trainees have participated actively in the monthly International Urology Journal Club on Twitter, although formal data are lacking.

Social Media for Continuing Professional Development

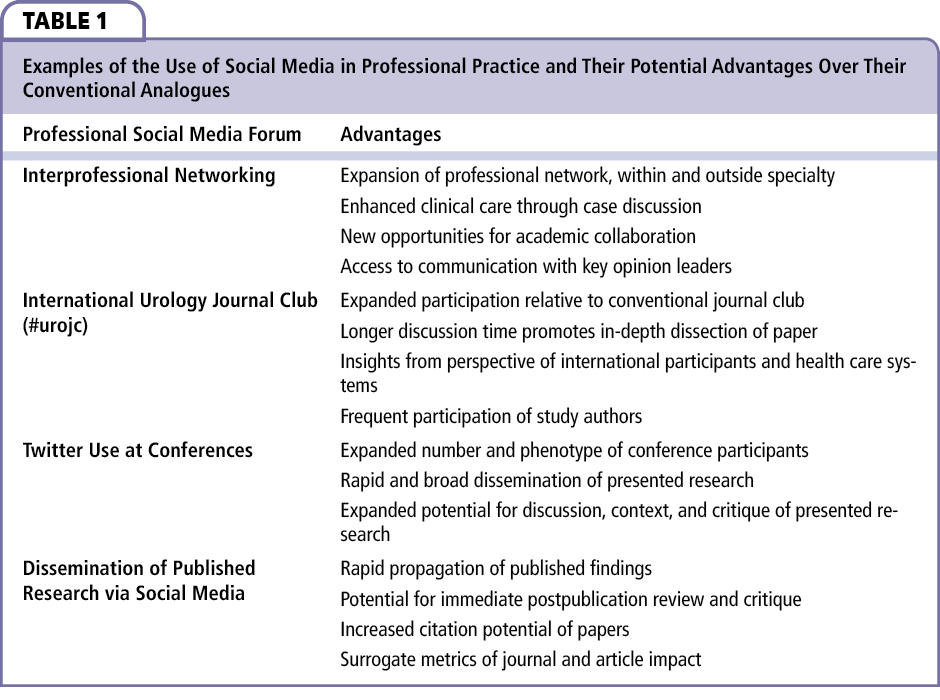

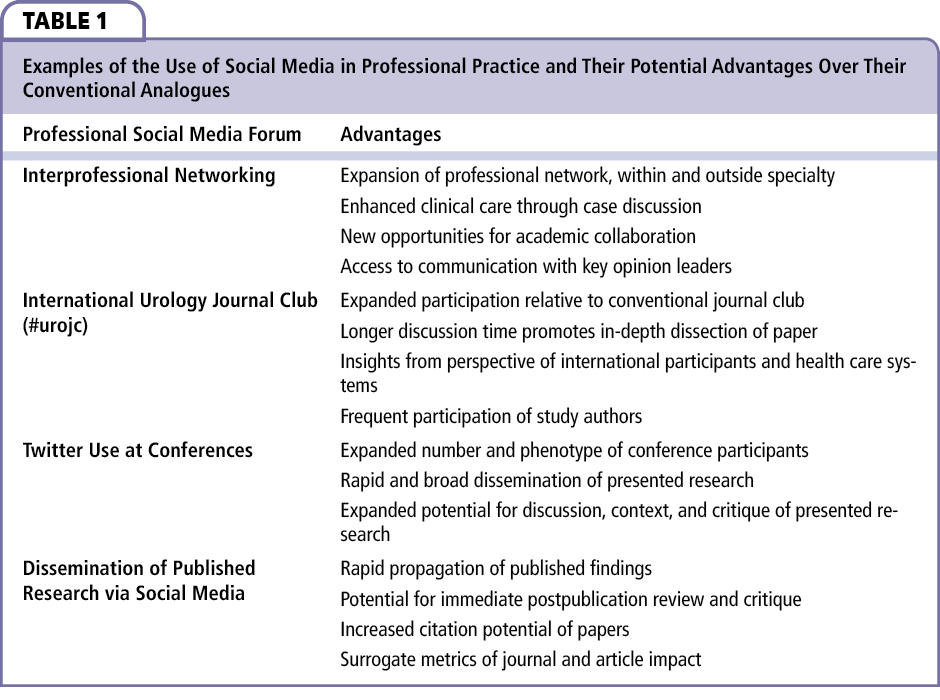

The use of Twitter for continuing professional development has emerged as the most prominent distillate of social media in urology. Even before data became available to allow quantitative assessment of these developments, there were a number of calls to arms in prominent urology journals, espousing and enumerating the purported virtues of participation.12-14 Examples of the use of social media in the professional setting and their possible advantages are presented in Table 1.

The basic output of Twitter is the tweet, a character-limited message delivered to other user accounts that have subscribed to (or “followed”) the sending user. These can be text-only or may feature appended images or Web links. Tweets are generally also publicly visible through Internet search, or through tagging within the service through the use of hashtags, the small text strings preceded by the # symbol that may be included in tweets. These may be subsequently searched for, resulting in a collated list of tweets featuring that hashtag. Direct replies to tweets are also possible (standard within the conversational paradigm that defines social media), as are “retweets,” or rebroadcasts of tweets to another user’s followers. Retweeting is the hallmark of message amplification within Twitter.

Twitter at Urology Meetings

Objective buy-in and expansion of social media activity among health professionals has been seen quite clearly in discussions during and around clinical congresses. Medical organizations, including the AUA and the European Association of Urology (EAU), as well as smaller national associations, have formally adopted and promoted the use of year-specific meeting hashtags (for example, the self-explanatory #eau14 and #aua14) through which delegates and outside participants may contribute to the dialogue surrounding the meeting. Twitter metrics for meetings of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), the American Society of Nephrology, the Academic Surgical Congress, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have published data on the number of users, tweets, and interactions at their annual meetings.15-18 The RSNA noted a 37% increase in the number of in-meeting tweets between the 2011 and 2012 annual meetings, as well as a 48% increase in the number of tweeting accounts, from 755 to 1116.15 ASCO saw a similar rise in Twitter volume, with 83% more tweets arising from the 2011 meeting as compared with 2010.18

Urologic congresses have seen a similar rise in Twitter use, outpacing the above meetings with fivefold increases in both the tweet volume and the number of users between 2012 and 2013 at the AUA and Canadian Urological Association (CUA) annual meetings.19 There were 811 tweets from 134 accounts broadcast from the 2012 meetings, increasing to 4590 tweets from 540 users in 2013. Also notable was a shift in the primacy of user phenotype from biotechnology analysts in 2012 (28% of tweets) to urologists in 2013 (60% of tweets, up from 19%). This study also used a previously described classification scheme to qualify Twitter output as informative or noninformative, based on the content of the individual messages. Forty-one percent of 2013 tweets were deemed informative, that is, directly referencing or discussing meeting research. Advertisements, general user status updates, and conversational replies comprised the uninformative tweets. It should be noted that “uninformative” by this scheme does not necessarily imply that a tweet is not of interest to viewers of the messages, but that it did not specifically discuss research output. Unpublished but externally compiled data from the 2014 AUA Annual Meeting (#aua14) shows a continued rise in Twitter uptake.20 Over the six meeting days, 1144 distinct users broadcast 9938 tweets, 144% and 151% increases over 2013, respectively. The EAU annual meetings witnessed a similar rise in participation, from 1657 tweets from 219 accounts in 2013 (#eau13) to 5582 tweets from 744 accounts in 2014 (#eau14).21,22 These metrics also include a surrogate for the potential reach of the messages, known as “impressions,” defined as the number of times any tweet featuring a given hashtag enters the subscribed feed of any other users. The #eau14 hashtag had over 6.9 million impressions; the potential reach of #aua14 was 13.3 million impressions.

International Urology Journal Club

Another initiative that has arisen over social media is known as a Tweetchat, a timed discussion over a short period with each tweet appended with a chat hashtag. This has taken several forms, with well-subscribed discussions such as Healthcare Communications and Social Media (#hcsm), Medical Education Chat (#meded), and Breast Cancer Social Media (#bcsm), which includes patients among its participants.23,24 This model has also been adapted to the traditional journal club, affording discussion around a single paper, collated via the journal club’s hashtag. The International Urology Journal Club (#urojc) was first held in November 2012. The main features of this discussion are its asynchronous 48-hour duration, which allows participation from global time zones at convenient times, free availability of the article by the publishers, and unrestricted access to participation. Data from the first 12 months have been published; 189 different users participated from 19 countries and contributed an average of 195 tweets per month.25 The first or corresponding author participated in seven of the 12 discussions, and there was no attrition in the number of participants over time. The journal club #urojc is held for 48 hours beginning at 20:00 GMT on the first Sunday of each month.

Dissemination and Impact of Urologic Research

The emergence and adoption of social media (by physicians as well as professional associations and medical journals) has opened new sharing and discussion venues for the scientific literature. Conventional measures of a journal’s prominence, such as impact factor, have relied on future citations of its publications as endorsements of merit. The rapid sharing and dissemination of information over social media seems suited, if captured quantitatively, to offer surrogate measures of impact over a shorter time frame. Haustein and colleagues found that 9.4% of PubMed-indexed articles had been tweeted at least once, increasing from 2.4% in 2010 to 20.4% of 2012 articles; 3725 of 3812 journals (97.7%) had had at least one article tweeted.26

Authors have suggested, and indeed many journals have collected, such “altmetrics” to quantify article-level impact of individual studies.27,28 Such metrics include the number of times a paper is downloaded or viewed from a journal’s Web site, the number of tweeted links to an article, blog post mentions or commentaries, bookmarks to online referencing libraries, and other social media sharing. Thelwall and colleagues28 found that article-level metrics correlated with traditional citations, but that the effects of time (that is, older articles were published at a time when fewer users were on social media services and therefore the potential for dissemination was lower) should be kept in mind when using them.28

Darling and colleagues29 investigated the “life cycle” of scientific publications, highlighting early-stage benefits of professional network generation, idea development and iteration through discussion and prereview, and the rapid and amplified dissemination highlighted above. In their field of study, they found that researchers active in social media were followed on Twitter by an average of seven times as many people as the number of members in their academic departments. Fifty-five percent of followers were found to be academically active, with some potential for collaboration. The authors note the potential for tweeted links to reach policy makers, journalists, and other stakeholders who may not have been exposed through traditional academic publishing routes. Papers that are tweeted widely in their first days after publication were shown to be 11 times more likely to be cited traditionally up to 2 years after publication. Postpublication critique is noted as a key role in the social media life of a publication. Typically, published responses to a manuscript may appear several months after initial publication; social media allows for discussion and critique almost instantly, either in the small scale of individual posts or in online journal clubs, as noted previously.

Urology Patients Online

A large-scale survey by the Pew Research Internet Project found that 72% of US patients searched for health information online, which suggests a space in which physician presence and input would be valued.30 Online patient communities have arisen among patients with any number of shared ailments or advocacy goals. The popular site Patients Like Me connects patients into such communities, providing a de facto social network for communication of advice and support, in exchange for allowing the site to use anonymized data for research purposes.31 More general social media sites have developed innumerable pages and groups representing patients and advocates of numerous urologic diseases and diagnoses. Researchers have assessed the breadth and veracity of health information available on social media sites relating to urologic disease. Social media sites were not found to provide meaningful information for urinary incontinence, instead highlighting a high volume of advertising.32 YouTube was found to have useful information related to kidney stones (58%), but prostate cancer videos were found to suffer from bias (69%) or poor information quality (73%).33,34

Social media and specific Internet sites have allowed a new forum in which patients may rate their physicians over a variety of practice, personality, and skill parameters. Ellimoottil and colleagues35 analyzed a sample of 500 urologists’ online ratings. Positive ratings were given in 86% of cases, although based on fewer than three reviews per urologist. Ferrara and colleagues corroborated these positive reviews across the Canadian province of Ontario.36 The mean rating of urologists was 3.96/5. In this article, an explicitly mentioned diagnosis of cancer or good bedside manner resulted in higher ratings, whereas discussion of vasectomy or poor bedside manner was associated with lower ratings. Long comments, as well as those with words or phrases written in all capital letters, tended to have an angrier tone, associated with lower ratings.

Interestingly, the survey of Canadian urologists found that a small majority (56%) felt that privacy and boundary issues would totally prohibit interaction with patients online, with 65% endorsing a zero-contact approach.4 Despite the perception of current barriers, 73% acknowledged that they felt patient contact online would be inevitable in the future as technology and legislative guidance progressed.

Concerns, Caveats, and Professionalism Online

A major issue that arises in discussions and debates around the use of social media by professionals is a perception of an increased risk of discipline arising from online activities. The permanence of posted material, as well as the lack of control of others’ opinions about posted content may lead clinicians to avoid participation. The lay press has indeed highlighted cases of frankly inappropriate behavior and ensuing punishment. The issues of risk are not limited to concerns about posting explicit medical advice and attendant liability issues, but about others’ perceptions that the words and images that appear in online profiles are unprofessional. A survey of the executive directors of American state medical boards revealed that at least one online professionalism violation had been reported in 92% (44/48) of responding jurisdictions.37 Inappropriate communication with patients (69%) and misrepresentation of credentials (60%) were the most common violations. In 56% of the boards, punishment included suspension or revocation of physicians’ licenses.

Professionalism concerns and patient boundary issues have remained front-of-mind in counterarguments against the proliferation of social media in professional practice. These, of course, are not the only risks or caveats that may be considered. The permanence of posts is considered a drawback, as current context may be lost or forgotten if a message is rehashed at a future time.38 Lack of peer review in blog posts or “cherry-picked” citations may be concerning if opinions are stated as fact; this may engineer an air of trustworthiness to posted information that is not justified. Early academic work-in-progress posted for discussion may similarly suffer if propagated as though it were completed work. Concerns regarding the ability to separate useful information from a perceived torrent of uninformative or otherwise useless information may be reasonably manifest. Most social media services have options for content intake curation, including selective lists and collation filters, such as hashtags, to abrogate this concern. The high rate of noninformative content tweeted at the AUA and CUA meetings is testament to the issue of a low signal-

to-noise ratio, although classification as non-informative should not imply useless or uninteresting.19

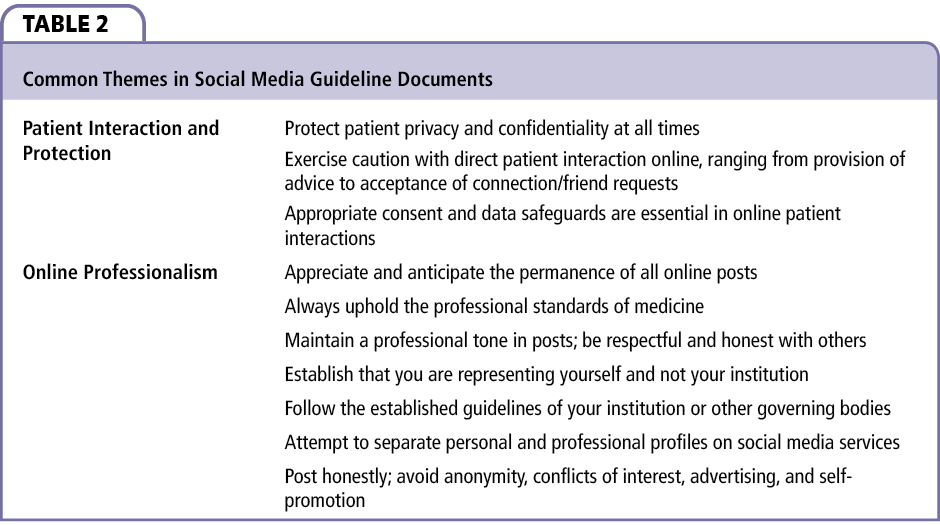

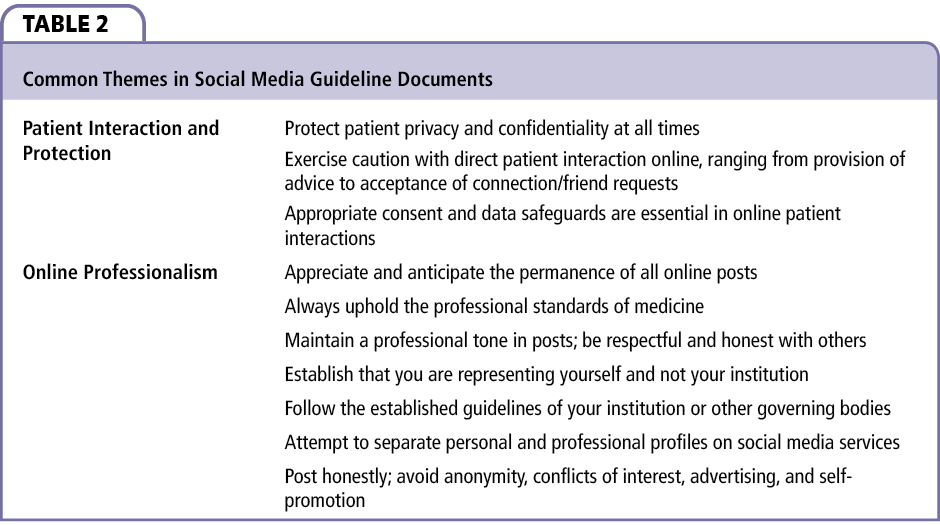

The American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards have published a comprehensive policy statement as guidance for online activities.39 They note the fluidity and evolution of social media in physician-patient interaction and highlight the potential benefits and innovations that may arise, but advise that the basic tenets of professionalism, already ingrained in medical education and practice, govern these interactions. They recommend specifically that physicians maintain separate private and public profiles in their online lives. Other authors, through the lens of professional ethics analysis, have elucidated the specific types of interaction and publication by and between physicians and patients online.40 The authors explicitly linked online activities to existing American Medical Association professional standards and have provided recommendations for appropriate navigation of the same. Numerous professional organizations, including the American and British Medical Associations, have also published guidelines for social media activities.41,42 It is important to note that in each case, although caveats specific to the novelty and novel modalities of online activity and patient interaction are noted, the ethical and professional principles are not unique, and adherence to these remains paramount, as in any aspect of professional life. At least one prominent editorial has taken the stance that separating public and private online identities is “operationally impossible,” arguing that the professional identity is inseparable from the personal, that the boundaries between the two are artificial, and that the burdensome effort of separating them may quash potential benefits or even cause harm within the relationship.43 Common threads uniting the various published guidelines are presented in Table 2.

In the survey of Canadian urologists by Fuoco and Leveridge, only 19% of urologists had read published guidelines for the professional use of social media.4 Ninety-five percent of those surveyed felt that caution must be exercised when posting online because of liability and discipline concerns. Most urologists agreed that they might face disciplinary action for posts perceived as unprofessional (89%); there was agreement that disciplinary action would be justified in this setting (68%). In their survey of AUA members, Loeb and colleagues found that 89% of urology trainees and 52% of consultant urologists had modified their social media privacy settings in order to make themselves less visible to public or patient users.3 Thirty-nine percent of urologists said that a patient or member of the public had contacted them via social media online. In recognition of the recent and anticipated expansion of urologists’ involvement in social media, and bearing similarity to other guidelines, Murphy and colleagues38 at the British Journal of Urology International have published 10 statements to guide the responsible use of social media by urologists. These guidelines center on the permanence of social media posts, the disclosure of identity and conflicts of interest, and respect for boundaries, confidentiality, and accuracy in their participation. Similar themes are addressed in guidelines from the EAU, who also note that a staged approach to initial participation may allow users to identify best practices before they engage themselves in the discussion.44

Conclusions

Social media have become so integrated into modern communications as to be universal in our personal and, increasingly, professional lives. In each domain of urologic practice, from patient interaction through research to continuing professional development, the move online has unlocked another layer of conversation, dissemination and, indeed, caveats. Social media have a democratizing effect, placing patients, trainees, practitioners, and thought leaders in the same arena and on equal footing. If uptake of social media in medicine even remotely parallels its rise to ubiquity in other areas, there is certain to be further expansion of its roles as described above, and novel uses will certainly continue to emerge. For these reasons, urologists should be aware of these technologies, as none is likely to be spared their impact in the future.

References

- Facebook Reports Second Quarter 2013 Results. Facebook Investor Relations Web site. http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=780093. Accessed April 30, 2014.

- Wickre, K. Celebrating #Twitter7. Twitter Blogs. https://blog.twitter.com/2013/celebrating-twitter7. Accessed April 30, 2014.

- Loeb S, Bayne CE, Frey C, et al. Use of social media in urology: data from the American Urological Association. BJU Int. 2014;113:993-998.

- Fuoco M, Leveridge MJ. Early adopters or laggards? Attitudes toward and use of social media among urologists [published online ahead of print July 1, 2014]. BJU Int. doi: 10.1111/bju.12855.

- Canadian physician use of social media remains low. Canadian Medical Association Future Practice. 2014 March; p4. https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/about-us/fp-march-2014-e.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2014.

- McGowan BS, Wasko M, Vartabedian BS, et al. Understanding the factors that influence the adoption and meaningful use of social media by physicians to share medical information. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e117.

- von Muhlen M, Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:777–781.

- Prensky M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. Part 1. On the Horizon. 2001;9:1-6.

- Purdy E, Leveridge MJ, Connelly R. Social media use by medical students and residency program directors. Presented at: 12th Canadian Conference on Medical Education; April 25-29, 2014; Ottawa, ON. Abstract CCME-PC9-2.

- Garner J, O’Sullivan H. Facebook and the professional behaviours of undergraduate medical students. Clin Teach. 2010;7:112-115.

- Fuoco M, Leveridge MJ. Residents’ use of and attitudes toward social media in urology. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(5-6 suppl 2):S81. Abstract MP-08.05.

- Murphy DG, Basto M. Social media @BJUIjournal – what a start! BJU Int. 2013;111:1007-1009.

- Loeb S, Catto J, Kutikov A. Social media offers unprecedented opportunities for vibrant exchange of professional ideas across continents. Eur Urol. 2014;66:118-119.

- Trinh QD. Why I care about social media—and why you should too. BJU Int. 2013;112:1-2.

- .Hawkins CM, Duszak R, Rawson JV. Social media in radiology: early trends in Twitter microblogging at radiology’s largest international meeting. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;11:387-390.

- Desai T, Shariff A, Shariff A, et al. Tweeting the meeting: an in-depth analysis of Twitter activity at Kidney Week 2011. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40253.

- Cochran A, Kao LS, Gusani NJ, et al. Use of Twitter to document the 2013 Academic Surgical Congress. J Surg Res. 2014;190:36-40.

- Chaudhry A, Glodé LM, Gillman M, Miller RS. Trends in Twitter use by physicians at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, 2010 and 2011. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:173-178.

- Matta R, Doiron C, Leveridge MJ. The dramatic increase in social media in urology. J Urol. 2014; 192:494-498.

- #aua14 Healthcare Social Media Analytics. The #aua14 Influencers. http://www.symplur.com/healthcare-hashtags/aua14/analytics/?hashtag=aua14&fdate=05%2F16%2F2014&shour=0&smin=0&tdate=05%2F22%2F2014&thour=0&tmin=0&ssec=00&tsec=00&img=1. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- #eau13 Healthcare Social Media Analytics. The #eau13 Influencers. http://www.symplur.com/healthcare-hashtags/eau13/analytics/?hashtag=eau13&fdate=03%2F15%2F2013&shour=0&smin=0&tdate=03-20-2013&thour=0&tmin=0&ssec=00&tsec=00&img=1. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- #eau14 Healthcare Social Media Analytics. The #eau14 Influencers. http://www.symplur.com/healthcare-hashtags/eau14/analytics/?hashtag=eau14&fdate=04%2F11%2F2014&shour=0&smin=0&tdate=04%2F16%2F2014&thour=0&tmin=0&ssec=00&tsec=00&img=1%5D. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- HealthSocMed | #hcsm (HealthSocMed) on Twitter. https://twitter.com/HealthSocMed. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- MedEd Chat (MedEdChat) on Twitter. https://twitter.com/MedEdChat. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Thangasamy IA, Leveridge M, Davies BJ, et al. International Urology Journal Club via Twitter: 12-month experience. Eur Urol. 2014;66:112-117.

- Haustein S, Peters I, Sugimoto CR, et al. Tweeting biomedicine: an analysis of tweets and citations in the biomedical literature. 2013;1-22. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1308.1838.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Neylon C, Wu S. Article-level metrics and the evolution of scientific impact. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000242.

- Thelwall M, Haustein S, Larivière V, Sugimoto CR. Do altmetrics work? Twitter and ten other social web services. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64841.

- Darling E, Shiffman D, CÔté I, Drew J. The role of Twitter in the life cycle of a scientific publication. Ideas in Ecology and Evolution. 2013;6:32-43.

- Fox S, Duggan M. Health Online 2013. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013/. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- PatientsLikeMe®. http://www.patientslikeme.com/. Accessed April 30, 2014.

- Sajadi KP, Goldman HB. Social networks lack useful content for incontinence. Urology. 2011;78:764-767.

- Sood A, Sarangi S, Pandey A, Murugiah K. YouTube as a source of information on kidney stone disease. Urology. 2011;77:558-562.

- Steinberg PL, Wason S, Stern JM, et al. YouTube as source of prostate cancer information. Urology. 2010;75:619-622.

- Ellimoottil C, Hart A, Greco K, et al. Online reviews of 500 urologists. J Urol. 2013;189:2269-2273.

- Ferrara S, Hopman W, Leveridge M. Diagnosis, bedside manner and comment style are predictive factors in 3288 patients’ online ratings of urologists. Urology Practice. 2014;1:117-121.

- Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, et al. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307:1141-1142.

- Murphy DG, Loeb S, Basto MY, et al. Engaging responsibly with social media: the BJUI Guidelines. BJU Int. 2014;114:9-11.

- Farnan JM, Snyder Sulmasy L, Worster BK, et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158: 620-627.

- Chretien KC, Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;127:1413-1421.

- Shore R, Halsey J, Shah K, et al. Report of the AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: professionalism in the use of social media. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22:165-172.

- British Medical Association. Using Social Media: Practical and Ethical Guidance for Doctors and Medical Students. 2012. http://bma.org.uk/-/media/Files/PDFs/Practical%20advice%20at%20work/Ethics/

socialmediaguidance.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2014. - DeCamp M, Koenig TW, Chisolm MS. Social media and physicians’ online identity crisis. JAMA. 2013;310:581-582.

- Rouprêt M, Morgan TM, Bostrom PJ, et al. European Association of Urology (@Uroweb) Recommendations on the Appropriate Use of Social Media [published online ahead of print July 16, 2014]. Eur Urol. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.046.