Penile Rehabilitation Strategies Among Prostate Cancer Survivors

Fouad Aoun, MD, MSc,1,2 Alexandre Peltier, MD,1,2 Roland van Velthoven, MD, PhD1,2

1Department of Urology, Jules Bordet Institute, Brussels, Belgium; 2Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

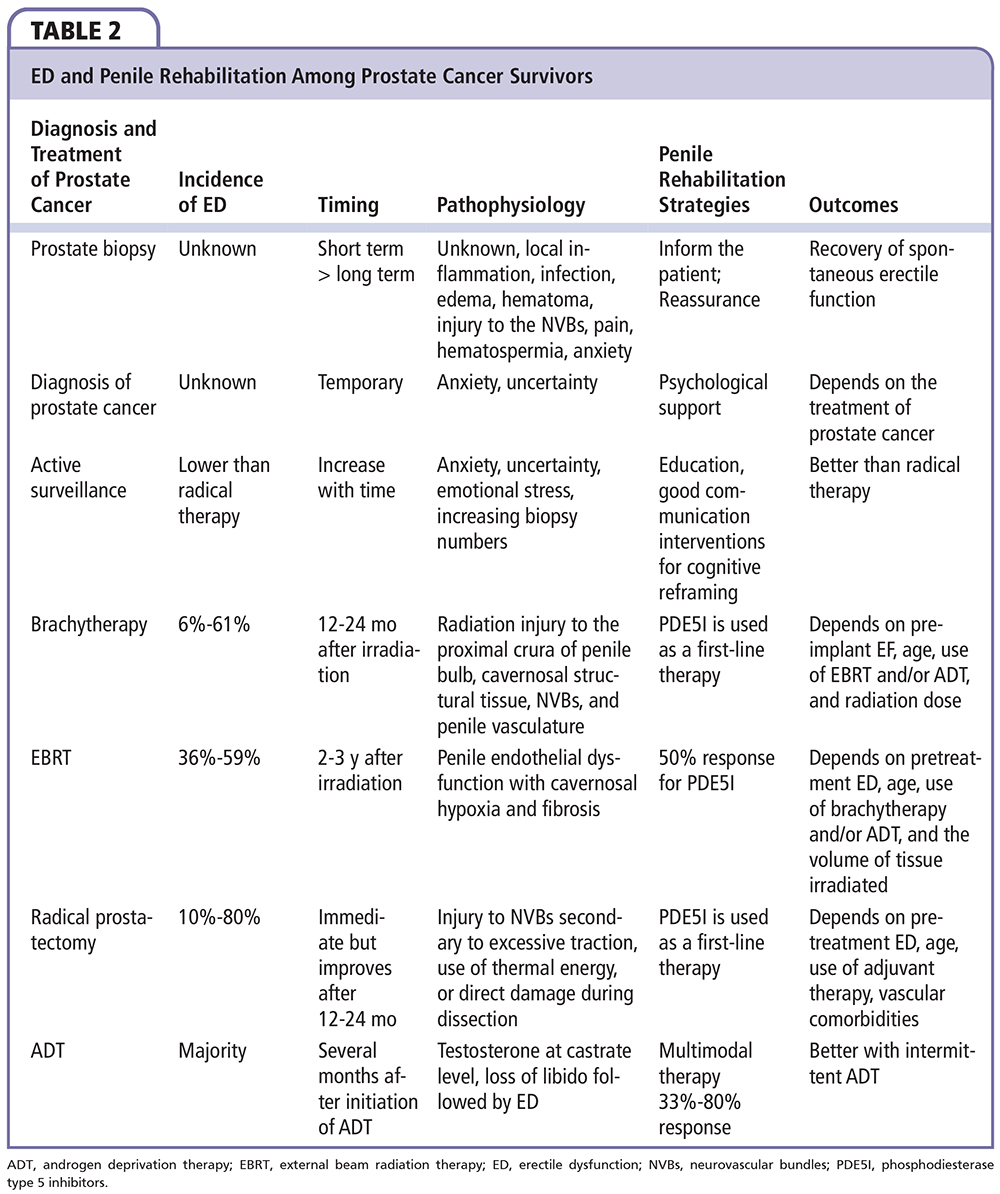

Despite advances in technical and surgical approaches, erectile dysfunction (ED) remains the most common complication among prostate cancer survivors, adversely impacting quality of life. This article analyzes the concept and rationale of ED rehabilitation programs in prostate cancer patients. Emphasis is placed on the pathophysiology of ED after diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer to understand the efficacy of rehabilitation programs in clinical practice. Available evidence shows that ED is a transient complication following prostate biopsy and cancer diagnosis, with no evidence to support rehabilitation programs in these patients. A small increase in ED and in the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors was reported in patients under active surveillance. Patients should be advised that active surveillance is unlikely to severely affect erectile function, but clinically significant changes in sexual function are possible. Focal therapy could be an intermediate option for patients demanding treatment/ refusing active surveillance and invested in maintaining sexual activity. Unlike radical prostatectomy, there is no support for PDE5 inhibitor use to prevent ED after highly conformal external radiotherapy or low-dose rate brachytherapy. Despite progress in the understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for ED in prostate cancer patients, the success rates of rehabilitation programs remain low in clinical practice. Alternative strategies to prevent ED appear warranted, with attention toward neuromodulation, nerve grafting, nerve preservation, stem cell therapy, investigation of neuroprotective interventions, and further refinements of radiotherapy dosing and delivery methods.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(2):58-68 doi: 10.3909/riu0652]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Penile Rehabilitation Strategies Among Prostate Cancer Survivors

Fouad Aoun, MD, MSc,1,2 Alexandre Peltier, MD,1,2 Roland van Velthoven, MD, PhD1,2

1Department of Urology, Jules Bordet Institute, Brussels, Belgium; 2Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

Despite advances in technical and surgical approaches, erectile dysfunction (ED) remains the most common complication among prostate cancer survivors, adversely impacting quality of life. This article analyzes the concept and rationale of ED rehabilitation programs in prostate cancer patients. Emphasis is placed on the pathophysiology of ED after diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer to understand the efficacy of rehabilitation programs in clinical practice. Available evidence shows that ED is a transient complication following prostate biopsy and cancer diagnosis, with no evidence to support rehabilitation programs in these patients. A small increase in ED and in the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors was reported in patients under active surveillance. Patients should be advised that active surveillance is unlikely to severely affect erectile function, but clinically significant changes in sexual function are possible. Focal therapy could be an intermediate option for patients demanding treatment/ refusing active surveillance and invested in maintaining sexual activity. Unlike radical prostatectomy, there is no support for PDE5 inhibitor use to prevent ED after highly conformal external radiotherapy or low-dose rate brachytherapy. Despite progress in the understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for ED in prostate cancer patients, the success rates of rehabilitation programs remain low in clinical practice. Alternative strategies to prevent ED appear warranted, with attention toward neuromodulation, nerve grafting, nerve preservation, stem cell therapy, investigation of neuroprotective interventions, and further refinements of radiotherapy dosing and delivery methods.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(2):58-68 doi: 10.3909/riu0652]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Penile Rehabilitation Strategies Among Prostate Cancer Survivors

Fouad Aoun, MD, MSc,1,2 Alexandre Peltier, MD,1,2 Roland van Velthoven, MD, PhD1,2

1Department of Urology, Jules Bordet Institute, Brussels, Belgium; 2Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

Despite advances in technical and surgical approaches, erectile dysfunction (ED) remains the most common complication among prostate cancer survivors, adversely impacting quality of life. This article analyzes the concept and rationale of ED rehabilitation programs in prostate cancer patients. Emphasis is placed on the pathophysiology of ED after diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer to understand the efficacy of rehabilitation programs in clinical practice. Available evidence shows that ED is a transient complication following prostate biopsy and cancer diagnosis, with no evidence to support rehabilitation programs in these patients. A small increase in ED and in the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors was reported in patients under active surveillance. Patients should be advised that active surveillance is unlikely to severely affect erectile function, but clinically significant changes in sexual function are possible. Focal therapy could be an intermediate option for patients demanding treatment/ refusing active surveillance and invested in maintaining sexual activity. Unlike radical prostatectomy, there is no support for PDE5 inhibitor use to prevent ED after highly conformal external radiotherapy or low-dose rate brachytherapy. Despite progress in the understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for ED in prostate cancer patients, the success rates of rehabilitation programs remain low in clinical practice. Alternative strategies to prevent ED appear warranted, with attention toward neuromodulation, nerve grafting, nerve preservation, stem cell therapy, investigation of neuroprotective interventions, and further refinements of radiotherapy dosing and delivery methods.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(2):58-68 doi: 10.3909/riu0652]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Prostate cancer • Erectile dysfunction • Penile rehabilitation • Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor • Prostaglandin E1

Key words

Prostate cancer • Erectile dysfunction • Penile rehabilitation • Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor • Prostaglandin E1

ED is also a prevalent long-term complication among prostate cancer patients receiving systemic therapy.

Penile corporal hypoxia, due to the loss of daily and nocturnal erections during rapid eye movement sleep, predisposes men to penile atrophy, smooth muscle apoptosis, veno-occlusive dysfunction, and penile scarring and fibrosis that limit further oxygenation, resulting in ED.

Pain, hematospermia, and anxiety associated with the possible diagnosis of prostate cancer, as well as an established prostate cancer diagnosis, adversely affect short-term erectile function.

Unlike RP patients, the majority of patients with brachytherapyinduced ED responded favorably to oral PDE5 inhibitors.

Recovery of erectile function is possible after discontinuation of ADT.

Main Points

• Despite advances in technical and surgical approaches, erectile dysfunction (ED) remains the most common complication among prostate cancer survivors, adversely affecting quality of life.

• The need for a rehabilitation program for patients undergoing prostate biopsy is debatable; some authors suggest the need for proper patient and partner counselling before and after the biopsy, whereas others are cautious to discuss ED with the patient unless confirmed data of anatomic nerve damage is available.

• Unlike radical prostatectomy, there is no support for phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor use to prevent ED after external radiotherapy or brachytherapy.

• Early erectile function rehabilitation seems to be critical to the recovery and maintenance of spontaneous penile erections after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy.

Main Points

• Despite advances in technical and surgical approaches, erectile dysfunction (ED) remains the most common complication among prostate cancer survivors, adversely affecting quality of life.

• The need for a rehabilitation program for patients undergoing prostate biopsy is debatable; some authors suggest the need for proper patient and partner counselling before and after the biopsy, whereas others are cautious to discuss ED with the patient unless confirmed data of anatomic nerve damage is available.

• Unlike radical prostatectomy, there is no support for phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor use to prevent ED after external radiotherapy or brachytherapy.

• Early erectile function rehabilitation seems to be critical to the recovery and maintenance of spontaneous penile erections after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy.

In the United States, prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed nonskin cancer in men, and is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death.1 In 2014, an estimated 233,000 men in the United States were diagnosed with a prostate cancer and 29,480 men were expected to die from their disease.2 In the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) era, the importance of this type of cancer becomes evident when considering that more young, sexually active men are being diagnosed at an early stage while the tumor is still organ confined. Early detection of prostate cancer in the PSA era, as well as improvements in systemic treatment of metastatic prostate cancer, has led to an increased life expectancy; but cancer diagnosis and treatment carry serious physical and psychological consequences that can dramatically decrease quality of life.3 However, these results had recently drawn the attention of the scientific community to the quality of life of cancer survivors in order to promote health as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).4 Despite advances in technical and surgical approach, erectile dysfunction (ED) remains the most common and the most documented complication among prostate cancer survivors, adversely impacting quality of life.5 ED is also a prevalent long-term complication among prostate cancer patients receiving systemic therapy6 In recent years, investigators have increasingly focused on ED in prostate cancer patients. They have directed their efforts toward searching for interventions that might improve erectile function. Various coping strategies and rehabilitation programs have been suggested and applied with different success rates.

This article provides an overview of the literature, analyzing the concept and rationale of rehabilitation programs for ED in prostate cancer patients. Emphasis is placed on the pathophysiology of such disorders after diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer in order to understand the efficacy of rehabilitation programs in clinical practice.

The Concept of Penile Rehabilitation

The penile erectile tissue, specifically the cavernous smooth musculature and the smooth muscles of the arteriolar and arterial walls, plays a key role in the erectile process. In the flaccid state, these smooth muscles are tonically contracted, allowing only a small amount of arterial flow for nutritional purposes. The blood partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) is approximately 35 mm Hg. Daily and nocturnal erections result from relaxation of these smooth muscles and a subsequent increase in diastolic and systolic blood flow. The increased blood flow leads to an increase in PO2 (to ∼90 mm Hg) and intracavernous pressure (∼100 mm Hg), allowing good oxygenation of the penile erectile tissue. Oxygenation of the cavernous tissue is important in the regulation of local mechanisms of erection. High blood flow during erections provides the free oxygen necessary for formation of nitric oxide (NO) by neuronal and endothelial NO synthase (NOS); low oxygen tension inhibits NOS activity and the release of NO in penile corpus cavernosum, regardless of the normal or physiologic state of the nerves and endothelium. The lack of free oxygen, transported to the penis by hemoglobin, is theoretically detrimental to the synthesis of NO and cyclic guanosine monophosphate formation.7 Penile corporal hypoxia, due to the loss of daily and nocturnal erections during rapid eye movement sleep, predisposes men to penile atrophy, smooth muscle apoptosis, veno-occlusive dysfunction, and penile scarring and fibrosis that limit further oxygenation, resulting in ED.8 The importance of smooth muscle relaxation and penile oxygenation has been corroborated in animal and human studies. Robust studies on rat models have demonstrated smooth muscle cell apoptosis as early as the first postoperative day after bilateral and unilateral cavernous neurectomy compared with a more delayed smooth muscle cell apoptosis after cavernous nerve crush injury.9 Smooth muscle apoptosis appears to be clustered in the subtunical area and contributes to venous leak when smooth muscle content in the penis drops below 40%.10 Another consequence of neurapraxia is alteration in the smooth muscle-collagen ratio, with increased levels of collagen types I and III, as well as elevated levels of transforming growth factor β.11 These changes have been associated with prolonged tissue hypoxia, leading many investigators to propose a causal relationship between hypoxia and the cavernosal changes.12 The use of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors in rat models resulted in preservation of corporal smooth muscle content, better endothelial factors, reduced apoptosis, and increased activity of NOS.13-15 Apoptotic indices of normal corporal smooth muscle measure approximately 10% in rats. In the bilateral cavernous nerve injury model, apoptotic indices are approximately 60% and drop to 20% during PDE5 inhibitor treatment.16 In clinical studies, ED was defined by the National Institutes of Health as the “inability to attain and/or maintain a penile erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance.”17 The WHO and the International Consultation on Urologic Disease had also endorsed this definition.18 The concept of early intervention to oxygenate the penile corporal, termed penile rehabilitation, was first suggested in 1997 by Montorsi and colleagues.19 Subsequently, several authors published the results of their rehabilitation programs and strategies with different types of PDE5 inhibitors, intracavernous injection of prostaglandin E1(PGE1), intraurethral application of PGE1, vacuum erectile devices (VED), and vibratory stimulators with different rates of success. It is noteworthy to mention that the rehabilitation strategies varied according to the mechanisms of ED and underlying pathology, but the principle of early intervention is the same for all patients.

ED After Prostate Biopsy: Is There a Penile Rehabilitation Strategy?

Prostate biopsy is the standard approach for the diagnosis of prostate cancer and is one of the most common invasive procedures in urology, accounting for 2 million interventions per year in Western developed countries.20 The indications for prostate biopsy include suspicious digital rectal examination findings and elevated PSA level, often considered in the context of other risk factors such as age, race, PSA velocity, comorbidities, and life expectancy. Biopsy is typically well tolerated, with a low risk of major complications.21

Patients may report ED after prostate biopsy. However, the exact incidence and pathophysiology of postbiopsy ED are unknown because data are sparse and heterogeneous, with significant confounders. Temporary local inflammation, infection, edema, hematoma, or injury to the neuro-vascular bundles could be a potential etiologic factor for postbiopsy ED.21 Pain, hematospermia, and anxiety associated with the possible diagnosis of prostate cancer, as well as an established prostate cancer diagnosis, adversely affect short-term erectile function.22,23 In a recent systematic review, a trend toward increased short-term (1 mo) incidence of ED following prostate cancer biopsy was noted, with studies showing follow-up of more than 3 to 6 months reporting lower incidence.21 A return to normal or to a milder degree of ED as measured by the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) score in patients with postbiopsy ED was also noted.24 Furthermore, the impact of anxiety and psychological factors is relevant, with some studies showing increased anxiety at the time of screening, biopsy, and immediately following biopsy.25 Higher ED rates were also reported following repeated or extensive biopsy or with the use of periprostatic local anesthetic nerve blocks.26,27 The need for a rehabilitation program for patients undergoing prostate biopsy is debatable. Some authors suggest the need for proper patient and partner counselling before and after the biopsy, whereas others are cautious to discuss ED with the patient unless confirmed data of anatomic nerve damage are available.28 Some physicians reassure the patient complaining of postbiopsy ED and encourage him temporarily by prescribing PDE5 inhibitors.28 Patients with biopsy-proven cancer had higher rates of ED, as well as deteriorations in sexual desire, orgasmic function, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction attributable to stress and anxiety related to the diagnosis of malignancy.22 However, there is no specific rehabilitation program for these nondemanding patients because the primary objective remains the treatment of their cancer.

Rehabilitation Programs in Prostate Cancer Patients Suitable for Active Surveillance

Active surveillance (AS) is a recent modality used for treating patients with low risk of progression of their prostate cancer in order to decrease overtreatment of potentially indolent cancers, to avoid risk and complications of radical therapies.29 Low-risk prostate cancer often follows an indolent clinical trajectory and the survival benefit of radical therapies is still debatable.29 An AS protocol entails repeating PSA testing, digital rectal examination, and prostate biopsy.29 Offering no treatment to cancer patients raises concern about how well men and their partners understand the natural prostate cancer trajectory and the available treatment modalities. It has been demonstrated that AS protocols are frequently associated with anxiety and uncertainty.30 Increased education and good communication can alleviate anxiety and uncertainty as can interventions for cognitive refraining.31 Inviting patients to become active participants in their management might enhance their sense of control, and the involvement of peer support groups might be beneficial.31 A small increase in ED and in the use of PDE5 inhibitors was reported in a small cohort of patients followed over time.27This could be attributed to anxiety and emotional stress associated with the presence of cancer with no radical treatment. Repeated prostate biopsies were also implicated.32 To date, three studies have evaluated ED with repeat prostate biopsies during an AS protocol.27,32,33 One prospective study using the IIEF-5 in 427 AS patients reported changes in sexual activity level for more than 20% of respondents during a 3.2-year median follow-up.32 Conversely, increasing biopsy number in another cohort of 333 men undergoing AS was a statistically independent factor responsible for ED.33 However, these data are difficult to interpret, given that aging during the years between biopsies may have independently led to worsening ED. Furthermore, the impact on erectile function in these cohorts was minimal, and significantly better than comparable cohorts of patients receiving radical therapy, as demonstrated by the study of van den Bergh et al.34 Men on AS were more frequently sexually active, and, if they were not sexually active, it was less often due to ED; if they were sexually active they had fewer problems getting or keeping an erection. There is no specific rehabilitation program for AS patients, but men need to be advised of the negative impact of radical therapies on erectile function compared with AS.31 Physicians should advise patients that treatment is unlikely to severely affect erectile function but may be associated with clinically significant changes in sexual function.31 Patients and their partners are encouraged to discuss sexual activity problems with their physicians. Physical and emotional disturbances are common in these patients.31 Proper psychological support is sometimes needed. Some physicians use “PSA treatment modalities” to reduce patients’ anxiety related to doing nothing while on AS.35 Results from the Reduction by Dutasteride of Clinical Progression Events in Expectant Management (REDEEM) Trial support the concept that 5a reductase inhibitors may decrease patient anxiety.35 This treatment modality should be avoided in rehabilitation strategies because it could adversely affect sexual activity by decreasing libido and aggravating ED.36 Another plausible strategy may be to focally ablate the cancer index lesion. Patients may be reassured that something is being done to destroy the tumor, and that such destruction might be associated with lower disease progression rates in the future in comparison with no treatment. In addition, tissue preservation could be associated with minimal impact on erectile function.37 Focal therapy could be an intermediate option for patients demanding treatment/refusing AS and invested in maintaining their sexual activity.

Penile Rehabilitation After Radical Prostatectomy: What Is the Evidence?

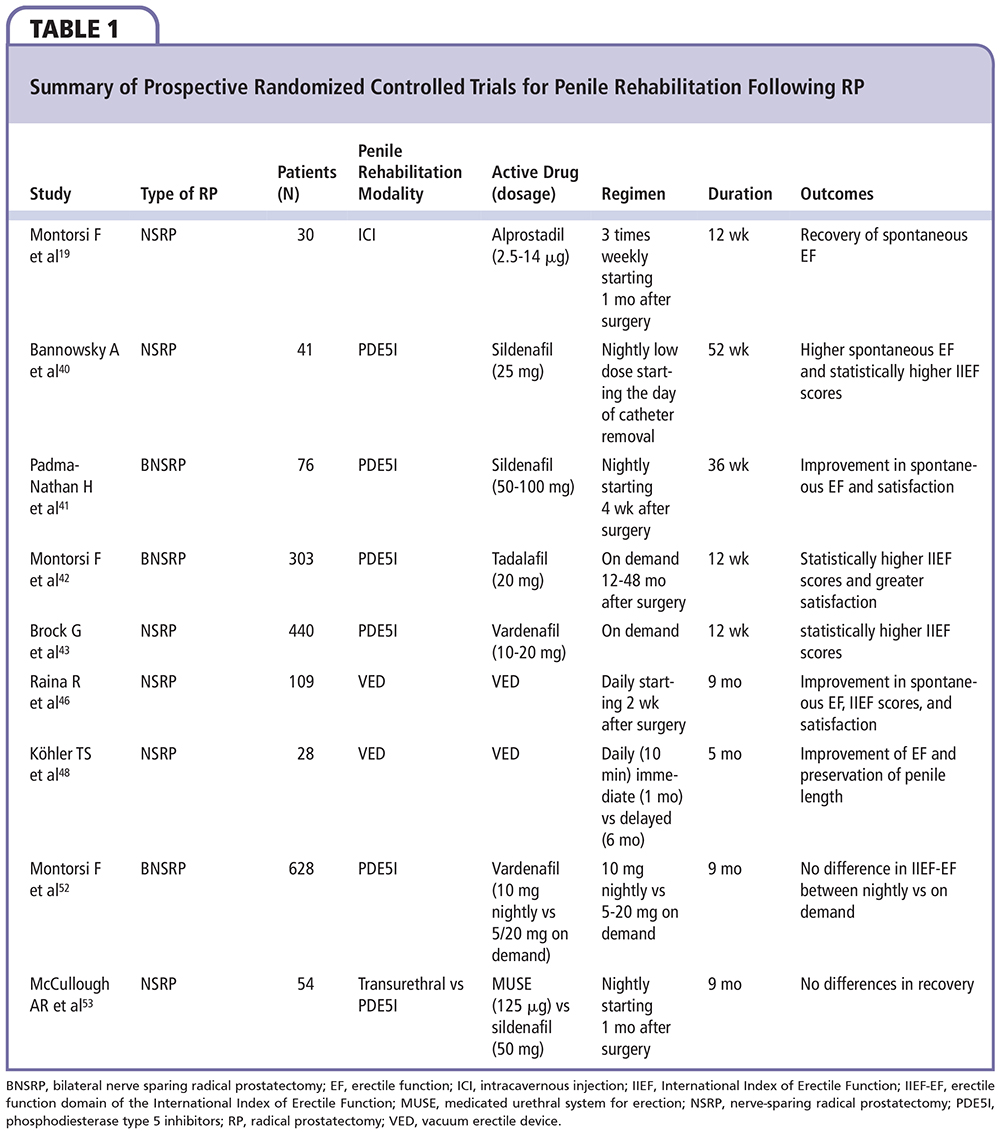

Historically, patients with ED after radical prostatectomy (RP) were observed and encouraged during the postoperative period to await the return of erectile function without the need for active intervention. The results of this approach were unsatisfactory both for the patient and the physician, because only 35.8% of patients left untreated after open bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (NSRP) recovered erectile function at a mean follow-up of 2 years after surgery.38In a prospective study, Montorsi and colleagues19 were the first to demonstrate the benefits of a rehabilitation program with intracavernous injection (ICI) of PGE1 in increasing the recovery rate of spontaneous erections after NSRP.19However, preoperative erectile function had not been assessed in their studies and no validated questionnaire had been used. Furthermore, the long-term benefit was not evaluated due to short follow-up time.19 In a non-randomized study, Mulhall and colleagues39 demonstrated the benefit of a rehabilitation program with PDE5 inhibitors (or ICI for nonresponders to PDE5 inhibitors) for patients with functional preoperative erections undergoing RP.39 Bannowsky and associates40 specified that sildenafil was significantly active in cases of early postoperative nocturnal erections. The findings obtained with the small patient sample by Padma-Nathan and associates41 showed that nightly sildenafil administration for 9 consecutive months, beginning 1 month postoperatively resulted in a greater return to baseline erectile function. These findings had also been confirmed, in clinical studies, for the other PDE5 inhibitors.42-44 In a large contemporary series of patients treated by high-volume surgeons, the 3-year erectile function recovery rates were significantly higher in patients who did use postoperative PDE5 inhibitors compared with patients who did not (73% and 37%, respectively; P < .001).45 Intraurethral alprostadil had also been used in rehabilitation programs. Raina and colleagues46 treated 56 men with intraurethral alprostadil (MUSE®; Meda Pharmaceuticals, Somerset, NJ) at doses of 125 mg and 250 mg three times weekly for 9 months. Although MUSE therapy avoids the needles associated with ICI, it is notable that almost one-third of men did not complete the study. Treatment was initiated 3 weeks postoperatively, and 40% of patients using MUSE reported having natural erections sufficient for vaginal intercourse. This non-compliance rate indicates, aside from side-effect disorders, that men need encouragement to continue with therapies that may not have immediate results. The same authors reported on the use of a VED as a rehabilitation therapy.47 However, the results were inconclusive. Köhler and coworkers48 reported higher rates of compliance due to better results of therapy in a group of patients treated as early as 1 month with VED compared with a control group treated 6 months later with VED.48 Further studies for VED as a rehabilitation therapy are needed, particularly because the mechanism of improving erectile function is unknown. The timing of rehabilitation is controversial in the literature. However, a general agreement based on experimental studies stresses that any form of rehabilitation should begin as soon after surgery as possible. Moskovic and colleagues49 described a “massive attack” rehabilitation program in which all the mentioned modalities were used, even beginning 1 week prior to surgery. In their studies, preoperative female partner sexual function correlated with greater patient compliance with the localized component of the ED rehabilitation program.49 Despite the increased demand for rehabilitation programs, a national survey in France found that only 38% of French urologists who responded to the survey systematically prescribed postoperative penile rehabilitation.50 In contrast, another survey among the members of the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) showed that some form of postoperative penile rehabilitation was performed in the majority of cases: 95% used PDE5 inhibitors, 75% used ICI, 30% used VED, and 9.9% used intraurethral prostaglandin.51 However, a selection bias could have been introduced because members of the ISSM are experts and do not represent common practitioners. In this survey, cost represented the most common reason for rehabilitation neglect, 25% were reluctant because they were not familiar with the concept, and another 25% were reluctant because of lack of evidence supporting penile rehabilitation.51 Some physicians used rehabilitation programs with on-demand intake of PDE5 inhibitors in order to reduce the cost. These physicians based their intervention on a multi-institutional, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study comparing 9 months of nightly dosing with vardenafil and flexible-dose on-demand vardenafil in patients who had a bilateral NSRP.52 Nightly dosing with vardenafil did not have any effect beyond that of on-demand use. Even more clinically relevant is the fact that this study confirmed that vardenafil taken when needed during the double-blind treatment period was associated with significantly better results compared with placebo. However, after the 2-month washout period and during the open-label phase, there were no significant differences in erectile function between groups. One could easily argue that the difference observed in the on-demand group could be attributable to the acute effect of the drug on penile hemodynamics combined with stimulation for sexual intercourse. In the absence of a documented neurotrophic or neuroprotective effect, the clinical key principle for penile rehabilitation is penile tumescence at least several times per week; PDE5 inhibitors are the simplest and most popular medical regimens for accomplishing this goal and are used as a first-line therapy.53 If this strategy fails, ICI should be used alone or in combination with PDE5 inhibitors. With the commercialization of the PGE1 cream, this could be an option if it is validated in penile rehabilitation strategies. The evidence from prospective randomized controlled trials for the use of penile rehabilitation in patients undergoing RP is summarized in Table 1.

Penile Rehabilitation After Brachytherapy

Prostate brachytherapy with permanent radioactive implants has recently gained popularity for curative treatment of localized prostate cancer, with the majority of the literature reporting biochemical results as favorable as those in RP and external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) series.54,55 It has been widely asserted that preservation of erectile function is more likely following brachytherapy compared with other curative treatment, but longer follow-up has raised substantial doubts about this advantage. Implantation of palladium-103 or iodine-125 with or without supplemental EBRT, with or without adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), results in ED in 6% to 61% of cases.56-67 Higher rates of ED were reported in series with longer follow-up.67,68 This could be due to the normal aging process or to the gradual effect of brachytherapy with time. Unlike RP, in which the effect is immediate, or EBRT, in which erectile function declines between 12 and 24 months after irradiation, the immediate decline in erectile function found after brachytherapy may be attributed to pain in general, discomfort and painful ejaculation, because only 25% of the calculated radiation is being emitted within 3 months after seed implantation, and ED tends to recover with time before declining again.69 The mechanisms contributing to ED after brachytherapy involve radiation injury to the proximal crura of penile bulb, cavernosal structural tissue, neurovascular bundles, and penile vasculature.70 In a series on brachytherapy using the IIEF-5 questionnaire, 52% of patients who underwent brachytherapy maintained erectile function at 6 years.57Several factors, including preimplant erectile function, age, use of supplemental EBRT, adjuvant ADT, radiation dose to the prostate gland and/or to the bulb of the penis, and diabetes, appear to exacerbate brachytherapy-related ED.58,71-74 Some studies reported strong correlation between the dose of radiotherapy delivered to the bulb of the penis and ED,73,74 whereas others found no such correlation and higher biochemical recurrence rates.75,76 Unlike RP patients, the majority of patients with brachytherapy-induced ED responded favorably to oral PDE5 inhibitors. This high response rate (83%-86%) reported in contemporary series renders brachytherapy beneficial from the aspect of quality of life, compared with RP, in which successful treatment of ED with oral PDE5 inhibitors depends on the preservation of the neurovascular bundles, with overall lower response rates (50%-80%).75-82 Although definitive evidence for a structured program of erectile function preservation with limited dose to the proximal crura and good response to oral PDE5 inhibitors is lacking, there is solid evidence for the acute efficacy of PDE5 inhibitors to treat ED after brachytherapy. In case of an association with an adjuvant ADT, a significant and profound loss of erectile function is encountered. This could be reversible in the majority of cases, but delayed and/ or incomplete recovery of erectile function or sometimes definitive ED after ADT withdrawal was observed. Therefore, patients who are receiving adjuvant ADT should be well informed about the possibility of such occurrences.

ED After EBRT

EBRT remains one of the primary treatment modalities for patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer. It is commonly used in the treatment of patients who have a greater likelihood of non-organ-confined disease. Advanced radiation techniques allow for safer delivery of higher radiation doses to the prostate and were assumed to cause less ED.83 However, ED remains one of the most common complication after EBRT, affecting 36%-59% of patients.84,85 The etiology of ED remains unclear, but the mechanism largely adopted, without a high level of evidence, is penile endothelial dysfunction with cavernosal hypoxia and fibrosis facilitated by the presence of pre-treatment ED, older age, concomitant use of ADT, and the volume of tissue irradiated.84,85 It is, however, unclear whether the dose to various parts of the penis, such as the penile bulb and corpora cavernosa, is related to the development of ED. Following radiotherapy, half of all men with ED use erectile aids with good results. Incrocci and associ-aes83,86 have reported efficacy of sildenafil and tadalafil in randomized trials for patients complaining of ED after three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) with 57% and 55% successful intercourse, respectively. A recent open-label extension of the blinded trial with tadalafil reported improvement in erections in 84% of patients and successful intercourse in 69%.86 Despite a good response rate to oral PDE5 inhibitors, spontaneous erection is not restored and treatment efficacy may wane over time. This may result in patient dissatisfaction with EBRT and a decline in psychosocial function among patients who underwent 3D-CRT and their partners, affecting their quality of life. According to a novel prospective randomized clinical trial, daily use of tadalafil compared with placebo did not result in improved erectile function after EBRT.87 There was no benefit to tadalafil as an ED prevention agent after radiotherapy. These findings do not support the scheduled once-daily use of tadalafil to prevent ED in men undergoing radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Alternative strategies to prevent ED in this context appear warranted, perhaps with attention toward alternative dosing, investigation of neuroprotective interventions, or further refinements of radiotherapy delivery methods. Sexologic support programs to patients and their partners are encouraged and oral PDE5 inhibitors are given on demand. Their effect wanes with time, probably due to the progressive decline of erectile function after EBRT, and use of ICI, intraurethral PGE1, and VED are encouraged for patients no longer responding to oral PDE5 inhibitors.

ED After ADT

ADT for prostate cancer is 75 years old and its use has markedly increased in the past two decades in Western countries.88 Physicians are becoming more familiar with the side effects associated with ADT, and prevention strategies and treatments exist for many of these side effects.89 ED develops in the overwhelming majority of patients receiving continuous ADT who were potent prior to therapy.90 Loss of libido in men receiving gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists usually develops within the first several months, and ED follows.90 ED can be treated with PDE5 inhibitors, ICI, MUSE, and VED. DiBlasio and colleagues91 retrospectively investigated 395 patients after bilateral orchidectomy or chemical castration for prostate cancer. ED response rates were noted in 335 (80%) patients on medical therapy, including 44% receiving PDE5 inhibitor monotherapy. Successful outcomes seem reasonable, particularly when implementing multimodal therapy. Testosterone levels in patients who reported or responded to ED-targeted therapy have not been measured in this study. Nevertheless, a success rate in ED treatment in such a population is unexpected, and prospective analysis using validated ED-directed instruments with a direct comparison with matched control subjects would be ideal to detect all potential relationships. Although these pharmacologic and mechanical approaches may restore the ability to achieve an erection, the lack of libido often limits patients’ enthusiasm for pursuing treatment to restore erections. ED should be anticipated and couples counselled before ADT is started. Sex therapists may be helpful in managing these issues once they become problematic. Recovery of erectile function is possible after discontinuation of ADT. Efforts have focused on the development of alternative hormone strategies that may permit sexually active men to retain potency. Antiandrogen monotherapy has been advocated as an alternative to ADT as a way to avoid some of the side effects associated with medical or surgical castration, but this approach is not considered an accepted alternative in current management guidelines.92 Intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) refers to cyclic administration of GnRH agonists with temporary withdrawal of therapy once a response has been achieved. Treatment is then reinitiated when there is evidence of progression. Based on current available evidence, IAD is not recommended for routine use and patients must be fully counselled on the limited data to support a benefit for this approach. However, a preliminary analysis of quality of life in patients under IAD suggested an improvement in sexual functioning.93

Conclusions

There is no consensus regarding the ideal regimen for penile rehabilitation therapy. The concept of early penile intervention is promising, but nearly all human studies have significant limitations that do not permit any type of definitive conclusions regarding the benefit of therapy. Proper patient and partner counselling before and after the diagnosis or treatment of cancer is mandatory. Patients should be informed about the potential risk of ED and about the potential benefits of an early penile rehabilitation. Early erectile function rehabilitation seems to be critical to the recovery and maintenance of spontaneous penile erections after NSRP. The understanding of nerve injury and nerve regeneration and its treatments will be an exciting research area in the next decade. Unlike penile rehabilitation for RP, there is no support for such an approach to prevent ED after EBRT or low-dose brachytherapy. Despite progress in understanding pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for ED in prostate cancer patients, limited clinical evidence and cost remain the principal factors limiting the widespread use of rehabilitation strategies in prostate cancer survivors. Recent neuromodulation strategies, nerve reconstruction, and stem cell use with the potential to minimize nerve injury promote nerve regeneration and/or protect endothelium and cavernosal smooth muscle are now limited to high-volume research centers but could be integrated in future rehabilitation programs. ![]()

The authors report no real or apparent conflicts of interest.

References

- DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252-271.

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statisitcs, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9-29.

- Victorson D, Barocas J, Song J, Cella D. Reliability across studies from the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) and its subscales: a reliability generalization. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:1137-1146.

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization: Chronicle of the World Health Organization. Vol 1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1947.

- Goldfarb S, Mulhall J, Nelson C, et al. Sexual and reproductive health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:726-744.

- DiBlasio CJ, Malcolm JB, Derweesh IH, et al. Patterns of sexual and erectile dysfunction and response to treatment in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102:39-43.

- Dean RC, Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:379-395.

- Hakky TS, Baumgarten AS, Parker J, et al. Penile rehabilitation: the evolutionary concept in the management of erectile dysfunction. Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15:393.

- User HM, Hairston JH, Zelner DJ, et al. Penile weight and cell subtype specific changes in a post-radical prostatectomy model of erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2003;169:1175-1179.

- Nehra A, Goldstein I, Pabby A, et al. Mechanisms of venous leakage: a prospective clinicopathological correlation of corporeal function and structure. J Urol. 1996;156:1320-1329.

- Iacono F, Giannella R, Somma P, et al. Histological alterations in cavernous tissue after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173:1673-1676.

- Brow SL, Seftel AD, Strohl KP, Herbener TE. Vasculogenic impotence and cavernosal oxygen tension. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12:19-22.

- Ferrini MG, Davila HH, Kovanecz I, et al. Vardenafil prevents fibrosis and loss of corporal smooth muscle that occurs after bilateral cavernosal nerve resection in the rat. Urology. 2006;68:429-435.

- Kovanecz I, Rambhatla A, Ferrini M, et al. Longterm continuous sildenafil treatment ameliorates corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction (CVOD) induced by cavernosal nerve resection in rats. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:202-212.

- Kovanecz I, Rambhatla A, Ferrini MG, et al. Chronic daily tadalafil prevents the corporal fibrosis and venoocclusive dysfunction that occurs after cavernosal nerve resection. BJU Int. 2008;101:203-210.

- Mulhall JP, Muller A, Donohue JF, et al. The functional and structural consequences of cavernous nerve injury are ameliorated by sildenafil citrate. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1126-1136.

- NIH Consensus Conference. Impotence. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Impotence. JAMA. 1993;270:83-90.

- Jardin A, Wagner G, Khoury S, et al., eds. Erectile Dysfunction. Birmingham, United Kingdom: Health Publication Ltd; 2000.

- Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF, et al. Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomized trial. J Urol. 1997;158:1408-1410.

- Shariat SF, Roehrborn CG. Using biopsy to detect prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2008;10:262-280.

- Loeb S, Vellekoop A, Ahmed HU, et al. Systematic review of complications of prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2013;64:876-892.

- Helfand BT, Glaser AP, Rimar K, et al. Prostate cancer diagnosis is associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction after prostate biopsy. BJU Int. 2013;111:38-43.

- Chrisofos M, Papatsoris AG, Dellis A, et al. Can prostate biopsies affect erectile function? Andrologia. 2006;38:79-83.

- Akbal C, Türker P, Tavukçu HH, et al. Erectile function in prostate cancer-free patients who underwent prostate saturation biopsy. Eur Urol. 2008;53: 540-544.

- Dale W, Bilir P, Han M, Meltzer D. The role of anxiety in prostate carcinoma: a structured review of the literature. Cancer. 2005;104:467-478.

- Klein T, Palisaar RJ, Holz A, et al. The impact of prostate biopsy and periprostatic nerve block on erectile and voiding function: a prospective study. J Urol. 2010;184:1447-1452.

- Braun K, Ahallal Y, Sjoberg DD, et al. Effect of repeated prostate biopsies on erectile function in men under active surveillance for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2014;191:744-749.

- Tuncel A, Kirilmaz U, Nalcacioglu V, et al. The impact of transrectal prostate needle biopsy on sexuality in men and their female partners. Urology. 2008;71:1128- 1131.

- Dall’Era MA, Albertsen PC, Bangma C, et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2012;62 :976-983.

- Kazer MW, Psutka SP, Latini DM, Bailey DE Jr. Psychosocial aspects of active surveillance. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23:273-277.

- Bergman J, Litwin MS. Quality of life in men undergoing active surveillance for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;45:242-249.

- Hilton JF, Blaschko SD, Whitson JM, et al. The impact of serial prostate biopsies on sexual function in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:1252-1258.

- Fujita K, Landis P, McNeil BK, Pavlovich CP. Serial prostate biopsies are associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction in men with prostate cancer on active surveillance. J Urol. 2009;182:2664-2669.

- van den Bergh RC, Korfage IJ, Roobol MJ, et al. Sexual function with localized prostate cancer: active surveillance vs radical therapy. BJU Int. 2012;110:1032- 1039.

- Fleshner NE, Lucia MS, Egerdie B, et al. Dutasteride in localised prostate cancer management: the REDEEM randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012; 2012;378:1103-1111.

- Amory JK, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM, et al. The effect of 5α-reductase inhibition with dutasteride and finasteride on bone mineral density, serum lipoproteins, hemoglobin, prostate specific antigen and sexual function in healthy young men. J Urol. 2008;179:2333- 2338.

- Van Velthoven R, Aoun F, Limani K, et al. Primary zonal high intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer: results of a prospective phase IIa feasibility study. Prostate Cancer. 2014;2014:756189.

- Gallina A, Ferrari M, Suardi N, et al. Erectile function outcome after bilateral nerve sparing radical prostatectomy: which patients may be left untreated? J Sex Med. 2012;9:903-908.

- Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, et al. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. J Sex Med. 2005;2:532-540.

- Bannowsky A, Schulze H, van der Horst C, et al. Recovery of erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: improvement with nightly low-dose sildenafil. BJU Int. 2008;101;1279-1283.

- Padma-Nathan H, McCullough AR, Levine LA, et al; Study Group. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of postoperative nightly sildenafil citrate for the prevention of erectile dysfunction after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:479-486.

- Montorsi F, Nathan HP, McCullough A, et al. Tadalafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction following bilateral nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol.2004;172:1036-1041.

- Brock G, Nehra A, Lipshultz LI, et al. Safety and efficacy of vardenafil for the treatment of men with erectile dysfunction after radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2003;170:1278-1283.

- Nehra A, Grantmyre J, Nadel A, et al. Vardenafil improved patient satisfaction with erectile hardness, orgasmic function and sexual experience in men with erectile dysfunction following nerve sparing radical prostatectomy. J Urol.2005;173:2067-2071.

- Briganti A, Gallina A, Suardi N, et al. Predicting erectile function recovery after bilateral nerve sparing radical prostatectomy: a proposal of a novel preoperative risk stratification. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2521-2531.

- Raina R, Pahlajani G, Agarwal A, Zippe CD. The early use of transurethral alprostadil after radical prostatectomy potentially facilitates an earlier return of erectile function and successful sexual activity. BJU Int. 2007;100:1317-1321.

- Pahlajani G, Raina R, Jones S, et al. Vacuum erection devices revisited: its emerging role in the treatment of erectile dysfunction and early penile rehabilitation following prostate cancer therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9: 1182-1189.

- Kohler TS, Pedro R, Hendlin K, et al. A pilot study on the early use of the vacuum erection device after radical retropubic prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2007;100:858-862.

- Moskovic DJ, Mohamed O, Sathyamoorthy K, et al. The female factor: predicting compliance with a postprostatectomy erectile preservation program. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3659-3665.

- Giuliano F, Amar E, Chevallier D, et al. How urologists manage erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: a national survey (REPAIR) by the French Urological Association. J Sex Med. 2008;5:448-457.

- Teloken P, Mesquita G, Montorsi F, Mulhall J. Postradical prostatectomy pharmacological penile rehabilitation: practice patterns among the International Society for Sexual Medicine Practitioners. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2032-2038.

- Montorsi F, Brock G, Lee J, et al. Effect of nightly versus on-demand vardenafil on recovery of erectile function in men following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;54;924-931.

- McCullough AR, Hellstrom WG, Wang R, et al. Recovery of erectile function after nerve sparing radical prostatectomy and penile rehabilitation with nightly intraurethral alprostadil versus sildenafil citrate. J Urol. 2010;183:2451-2456.

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Lief JH, Dorsey AT. Is brachytherapy comparable with radical prostatectomy and external-beam radiation for clinically localized prostate cancer? Tech Urol. 2001;7:12-19.

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Galbreath RW, Lief JH. Fiveyear biochemical outcome following permanent interstitial brachytherapy for clinical T1-T3 prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:41-48.

- Stock RG, Kao J, Stone NN. Penile erectile function after permanent radioactive seed implantation for treatment of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;165:436-439.

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Galbreath RW, et al. Erectile function after permanent prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:893-902.

- Merrick GS, Wallner K, Butler WM, et al. Short-term sexual function after prostate brachytherapy. Int J Cancer. 2001;96:313-319.

- Stock RG, Stone NN, Iannuzzi C. Sexual potency following interactive ultrasound-guided brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:267-272.

- Ragde H, Blasko JC, Grimm PD, et al. Interstitial iodine-125 radiation without adjuvant therapy in the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 1997;80:442-453.

- Zelefsky MJ, Wallner KE, Ling CC, et al. Comparison of the 5-year outcome and morbidity of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy versus transperineal permanent iodine-125 implantation for early-stage prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:517-522.

- Chaikin DC, Broderick GA, Malloy TR, et al. Erectile dysfunction following minimally invasive treatments for prostate cancer. Urology. 1996;48:100-104.

- Dattoli M, Wallner K, Sorace R, et al. 103Pd brachytherapy and external beam irradiation for clinically localized, high-risk prostatic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:875-879.

- Wallner K, Roy J, Harrison L. Tumor control and morbidity following transperineal iodine 125 implantation for stage T1/T2 prostatic carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:449-453.

- Zeitlin SI, Sherman J, Raboy A, et al. High dose combination radiotherapy for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998;160:91-95.

- Sharkey J, Chovnick SD, Behar RJ, et al. Outpatient ultrasound-guided palladium 103 brachytherapy for localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a preliminary report of 434 patients. Urology. 1998;51:796-803.

- Potters L, Torre T, Fearn PA, et al. Potency after permanent prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1235-1242.

- Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, et al. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54-61.

- Mabjeesh N, Chen J, Beri A, et al. Sexual function after permanent 125I-brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:96-101.

- Zelefsky MJ, Eid JF. Elucidating the etiology of erectile dysfunction after definitive therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:129-133.

- Merrick GS, Wallner K, Butler WM, et al. A comparison of radiation dose to the bulb of the penis in men with and without prostate brachytherapy-induced erectile dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:597-604.

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Dorsey AT, et al. A comparison of radiation dose to the neurovascular bundles in men with and without prostate brachytherapy-induced erectile dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1069-1074.

- Fisch BM, Pickett B, Weinberg V, Roach M. Dose of radiation received by the bulb of the penis correlates with risk of impotence after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57:955-959.

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, et al. The importance of radiation doses to the penile bulb vs crura in the development of postbrachytherapy erectile dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:1055-1062.

- Kiteley RA, Lee WR, deGuzman AF, et al. Radiation dose to the neurovascular bundles or penile bulb does not predict erectile dysfunction after prostate brachytherapy. Brachytherapy. 2002;1:90-94.

- Solan AN, Cesaretti JA, Stone NN, Stock RG. There is no correlation between erectile dysfunction and dose to penile bulb and neurovascular bundles following realtime low-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:1468-1474.

- Walsh PC, Marschke P, Ricker D, Burnett AL. Patientreported urinary continence and sexual function after anatomic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2000;55: 58-61.

- Zippe CD, Kedia AW, Kedia K, et al. Treatment of erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy with sildenafil citrate (Viagra). Urology. 1998;52:963-966.

- Lowentritt BH, Scardino PT, Miles BJ, et al. Sildenafil citrate after radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1999;162:1614-1617.

- Hong EK, Lepor H, McCullough AR. Time dependent patient satisfaction with sildenafil for erectile dysfunction (ED) after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP). Int J Impot Res. 1999;11(suppl 1):S15-S22.

- Vale J. Erectile dysfunction following radical therapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2000;57:301-305.

- Zagaja GP, Mhoon DA, Aikens JE, Brendler CB. Sildenafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2000;56:631-634.

- Incrocci L, Koper PC, Hop WC, Slob AK. Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) and erectile dysfunction following external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:1190-1195.

- van der Wielen GJ, Mulhall JP, Incrocci L. Erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer and radiation dose to the penile structures: a critical review. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84:107-113.

- Mendenhall WM, Henderson RH, Indelicato DJ, et al. Erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32:443-447.

- Incrocci L, Slagter C, Slob AK, Hop WC. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study to assess the efficacy of tadalafil (Cialis) in the treatment of erectile dysfunction following threedimensional conformal external-beam radiotherapy for prostatic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:439-444.

- Pisansky TM, Pugh SL, Greenberg RE, et al. Tadalafil for prevention of erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group [0831] randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1300-1307.

- Shahani S, Braga-Basaria M, Basaria, S. Androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer and metabolic risk for atherosclerosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2042-2049.

- Holzbeierlein JM. Managing complications of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:181-190.

- Schwandt A, Garcia JA. Complications of androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2009;19:322-326.

- DiBlasio CJ, Malcolm JB, Derweesh IH, et al. Patterns of sexual and erectile dysfunction and response to treatment in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102:39-43.

- Kunath F, Grobe HR, Rucker G, et al. Non-steroidal antiandrogen monotherapy compared with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists or surgical castration monotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD009266.

- Hussain M, Tangen CM, Berry DL et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1314-1325.