Expectations of Stress Urinary Incontinence Surgery in Patients With Mixed Urinary Incontinence

Benjamin M. Brucker, MD

NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY

Mixed urinary incontinence is estimated to affect 30% of all women who have urinary incontinence, and it has been shown to be more bothersome to women than pure stress incontinence. Given the degree of bother, many women will undergo surgical correction for incontinence. Patients have high expectations about the success of these interventions. Understanding mixed incontinence and the effects of our interventions can help guide therapeutic choices and manage patients’ expectations.

[Rev Urol. 2015; 17(1):14-19 doi: W.3909/riu0646]

© 2015 MedReviews ®, LLC

Expectations of Stress Urinary Incontinence Surgery in Patients With Mixed Urinary Incontinence

Benjamin M. Brucker, MD

NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY

Mixed urinary incontinence is estimated to affect 30% of all women who have urinary incontinence, and it has been shown to be more bothersome to women than pure stress incontinence. Given the degree of bother, many women will undergo surgical correction for incontinence. Patients have high expectations about the success of these interventions. Understanding mixed incontinence and the effects of our interventions can help guide therapeutic choices and manage patients’ expectations.

[Rev Urol. 2015; 17(1):14-19 doi: W.3909/riu0646]

© 2015 MedReviews ®, LLC

Expectations of Stress Urinary Incontinence Surgery in Patients With Mixed Urinary Incontinence

Benjamin M. Brucker, MD

NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY

Mixed urinary incontinence is estimated to affect 30% of all women who have urinary incontinence, and it has been shown to be more bothersome to women than pure stress incontinence. Given the degree of bother, many women will undergo surgical correction for incontinence. Patients have high expectations about the success of these interventions. Understanding mixed incontinence and the effects of our interventions can help guide therapeutic choices and manage patients’ expectations.

[Rev Urol. 2015; 17(1):14-19 doi: W.3909/riu0646]

© 2015 MedReviews ®, LLC

Key words

Urodynamics • Mixed urinary incontinence • Sling • Anti-incontinence surgery • Urgency incontinence

Key words

Urodynamics • Mixed urinary incontinence • Sling • Anti-incontinence surgery • Urgency incontinence

... it has not been shown that women with MUI who are treated with antimuscarinic agents have different outcomes compared with those with overactive bladder who do not have SUI.

... patients with low-pressure motor urge had the highest success rate of symptom resolution after treatment with a bladder neck sling (91.3%) and had a complete continence rate of 82.6%.

At 4 years, the TVT sling resulted in an 85% complete cure rate and an additional 4% of patients reported significantly improved symptoms...

Using multivariate analysis, DO was the biggest risk factor for persistence of urgency; however, sling type was also a factor for outcomes.

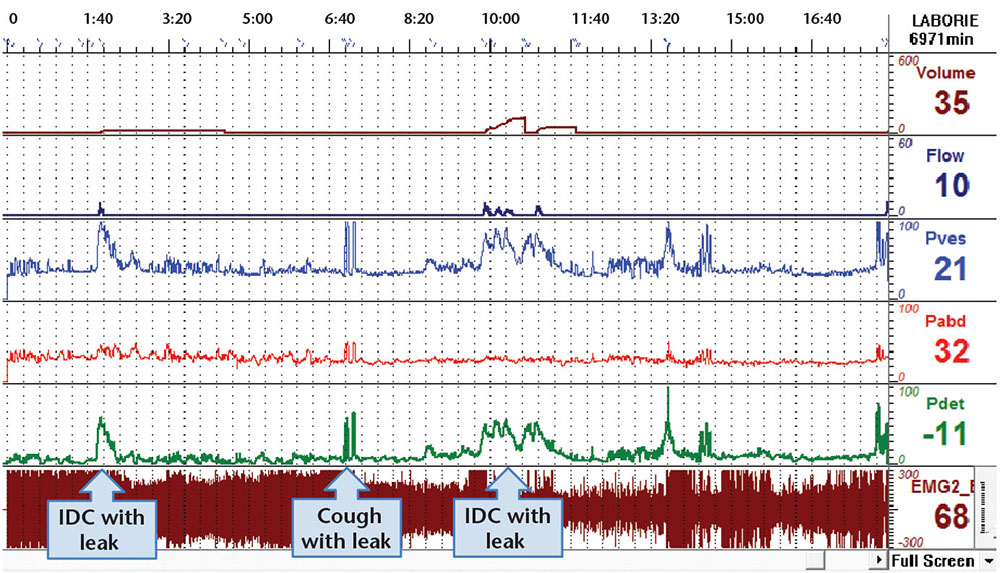

Figure 1. This is a sample urodynamic tracing of a woman with mixed urinary incontinence. Clinically she complained of leakage with activity as well as leakage associated with urgency.

The AUA guidelines on the surgical treatment of stress incontinence in women also state that SUI procedures may be considered for patients with MUI and a significant stress component...

Main Points

• Mixed urinary incontinence (MUl) is estimated to affect 30% of all women who have urinary incontinence, and it has been shown to be more bothersome to women than pure stress incontinence. As a result, many women seek surgical correction for incontinence. However, MUl can be a very challenging and costly condition to treat.

• Surgical options include autologous fascia pubovaginal slings, Burch colposuspension, as well as synthetic miduretheral slings and the tension-free vaginal tape sling. Urodynamic testing is often utilized when considering invasive therapies.

• Anti-incontinence sling surgery is not always the first choice, or the correct choice, for the management of MUl. However anti-incontinence sling surgery does fit into the treatment algorithm for treatment of MUl. When considering when to offer surgical options for MUl and how to council patients about expectations after these procedures, data from clinical studies must be evaluated to help identify preoperative predictors of success.

• If patients have persistence of urgency incontinence after surgery they will perceive the procedure to have failed. This highlights the importance of preoperative counseling in patients with MUl who are going to be treated with surgery.

Main Points

• Mixed urinary incontinence (MUl) is estimated to affect 30% of all women who have urinary incontinence, and it has been shown to be more bothersome to women than pure stress incontinence. As a result, many women seek surgical correction for incontinence. However, MUl can be a very challenging and costly condition to treat.

• Surgical options include autologous fascia pubovaginal slings, Burch colposuspension, as well as synthetic miduretheral slings and the tension-free vaginal tape sling. Urodynamic testing is often utilized when considering invasive therapies.

• Anti-incontinence sling surgery is not always the first choice, or the correct choice, for the management of MUl. However anti-incontinence sling surgery does fit into the treatment algorithm for treatment of MUl. When considering when to offer surgical options for MUl and how to council patients about expectations after these procedures, data from clinical studies must be evaluated to help identify preoperative predictors of success.

• If patients have persistence of urgency incontinence after surgery they will perceive the procedure to have failed. This highlights the importance of preoperative counseling in patients with MUl who are going to be treated with surgery.

It has been estimated that approximately 30% of women with urinary incontinence have mixed urinary incontinence (MUI). Degree of bother is higher among women with MUI compared with those who have pure stress urinary incontinence (SUI).1 MUI can be a very challenging and costly condition to treat.2,3 Patients with MUI are often offered conservative therapy such as physical therapy, weight-loss strategies, and behavioral modification. Some patients also benefit from treatments aimed directly at urgency, frequency, and urgency incontinence (overactive bladder), which currently include pharmacologic therapy (antimuscarinic or β-3 agonists), chemodenervation (botulinum toxin), or neuromodulation (sacral or posterior tibial nerves).4 However, many patients with MUI progress to surgical therapies for treatment of SUI. This article reviews the literature available that can help clinicians manage expectations of SUI surgeries on patients with MUI.

Defining and Understanding MIU

Overall success rates for stress incontinence surgery for patients with MUI vary in the literature from 36% to 87%.4-6 This variability comes from the differences in surgical procedures performed, outcomes measured, length of follow-up, and how MUI is defined. Though clinical studies have used different definitions, criteria, or cutoffs, the most current International Continence Society definition of MUI is “the complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency and also with effort or physical exertion or on sneezing or coughing.”7

To help understand the underlying cause of MUI, two etiologies have been prominently suggested. The first involves two distinct pathologies. It is suggested that urgency incontinence comes from bladder dysfunction and SUI comes from bladder outlet (and or urethral) dysfunction. The alternative mechanism underlying MUI suggests that is based on a common urethrogenic mechanism. This common pathway assumes that urine enters the proximal urethra and activates a facilitative detrusor reflex.8 The fact that, in some cases, urgency and/or urgency incontinence improves after SUI surgery suggests that the common pathway etiology may be correct.9 However, this is not always the case. Further, it has not been shown that women with MUI who are treated with antimuscarinic agents have different outcomes compared with those with overactive bladder who do not have SUI. Regardless of the actual mechanisms, surgery for SUI may be considered for patients with MUI. Proponents of the common pathway may consider surgery earlier in the treatment algorithm, but those who support the two distinct pathways will need multiple treatments to address both components. Ultimately, degree of bother and severity of these complaints may also help clinicians choose appropriate treatment regimens. When discussing treatment of mixed incontinence one must remember that “for treatment to be successful both the stress and urge components of the incontinence need to respond to the therapies.”10

Clinical Studies

Anti-incontinence sling surgery is not always the first choice, or the correct choice, for the management of MUI. However anti-incontinence sling surgery does fit into the treatment algorithm for treatment of MUI. When considering when to offer surgical options for MUI and how to counsel patients about expectations after these procedures, we need to synthesize the available data; to do this we often group like patients and compare the outcomes across these groups. A good example of some of the earliest work that attempted to understand outcomes of anti-incontinence procedures in the MUI population looked at women treated with autologous fascial bladder neck slings. The study used urodynamic parameters (in this case, videourodynamics) to predict outcomes. Although this work may be outdated because of the sling type, it illustrates observations that have helped clinicians manage patient expectations. The study ultimately looked at 70 patients with the complaint of urge who also had SUI (abdominal leak point pressure < 100 cm H2O, open bladder neck, hypermobility).11 They divided subjects into those with sensory urgency (symptom of urgency but no involuntary detrusor contraction) and those with motor urge (symptom of urgency and involuntary detrusor contraction). The patients with motor urge were further divided into low-pressure motor urge and high-pressure motor urge groups based on the amplitude of the involuntary detrusor contraction. The conclusion was that the patients with low-pressure motor urge had the highest success rate of symptom resolution after treatment with a bladder neck sling (91.3%) and had a complete continence rate of 82.6%.

This concept of identifying preoperative predictors of success in the MUI population was also performed in a secondary analysis of the Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial (SISTEr).12 The authors looked at preoperative questionnaires to predict outcomes. The study included patients with predominant SUI and randomized them to Burch colposuspension versus autologous fascia pubovaginal sling (PVS). The odds ratio of having postoperative urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) was 4.14 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.40-7.15) for each 10-unit increase in Medical, Epidemiologic and Social Aspect of aging (MESA) urge score. Prior anticholinergic therapy and the presence of detrusor over activity (DO) on urodynamic studies (UDS) were also preoperative predictors of postoperative UUI symptoms and initiation of treatment for UUI at 6-week follow-up. From this same study published 2-year data showed that women with higher preoperative urge scores actually had higher SUI-specific failure, in addition to higher overall failure rates (4× higher failure per 10 points on MESA).13 The authors’ suggested explanation for the overall failure rates was that, in the women with MUI, the “...urge symptoms serve as a surrogate or manifestation of intrinsic deficiency of the urethral sphincter from more advanced neuromuscular dysfunction...”13

It is also useful to look at the SISTEr trial to better understand how the type of anti-incontinence surgery may influence outcomes in patients with mixed symptoms. Kenton and colleagues12 looked at a group of women in the SISTEr trial who had been previously treated with antimuscarinic agents and/ or demonstrated DO on UDS; they found that there was a trend for patients to have persistent UUI with PVS compared with Burch colposuspension (29% vs 41 %; P = .07). In women with no prior treatment for urgency or DO on UDS the PVS-treated group had a 1.74 odds ratio of developing de novo UUI when compared with those who had Burch colposuspension at 6 weeks.

Most of the larger randomized trials in urinary incontinence do not primarily include patients with MUI. Some studies, however, focus on the surgical treatment of MUI. For example, a group of 75 women with complaints of MUI but without DO on UDS were treated with an anticholinergic agent, PVS, or Burch colposuspension.14 A control group was also included: a genuine SUI population treated with PVS or Burch colposuspension. The finding was that 85% of the surgery group was dry postoperatively—a better outcome than in the group treated with anticholinergic medication. The residual urge in the MUI group was no higher than the rate of developing de novo urge in the genuine SUI patients who were treated surgically.

One of the limitations of trying to study MUI patients as part of incontinence outcomes research is the lack of empirically derived definitions of the condition. Brubaker and colleagues10 attempted to classify MUI, but were ultimately unsuccessful. The percentage of patients in the study population with MUI varied from 8.3% to 93.3%, depending on the definition. None of the definitions (based on MESA, Urinary Distress Inventory 8, UDS, and 3-day voiding diary) predicted outcomes of anti-incontinence surgery.

We have explored treating MUI with anti-incontinence procedures and the data suggest that the type of procedure must be considered. PVS and Burch colposuspension have already been discussed, but synthetic miduretheral slings (MUS) are much more commonly performed today for treatment of SUI and MUI. The tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) sling was studied prospectively in 80 women with MUI (based on UDS).15 At 4 years, the TVT sling resulted in an 85% complete cure rate and an additional 4% of patients reported significantly improved symptoms; 11% of procedures were considered failures. Other studies of the TVT have looked more specifically at resolution of urge based on subjective and objective criteria. Duckett and Tamilselvi16 retrospectively looked at 6-month data of women with SUI and DO on UDS who were treated with TVT. This study found that there was a 63% subjective resolution of urge based on the questionnaire and a 47% objective resolution of DO on UDS.

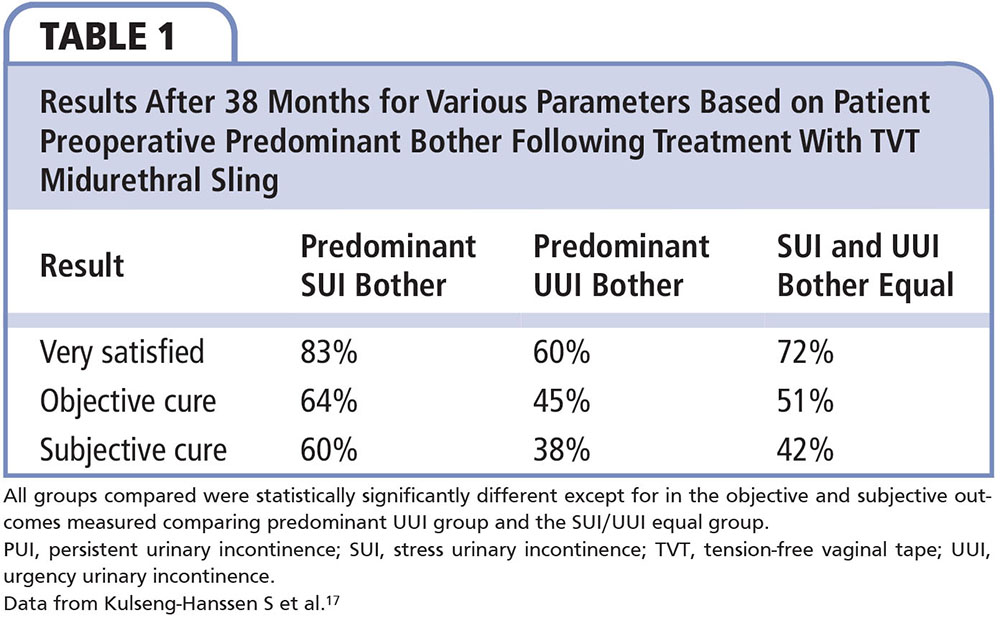

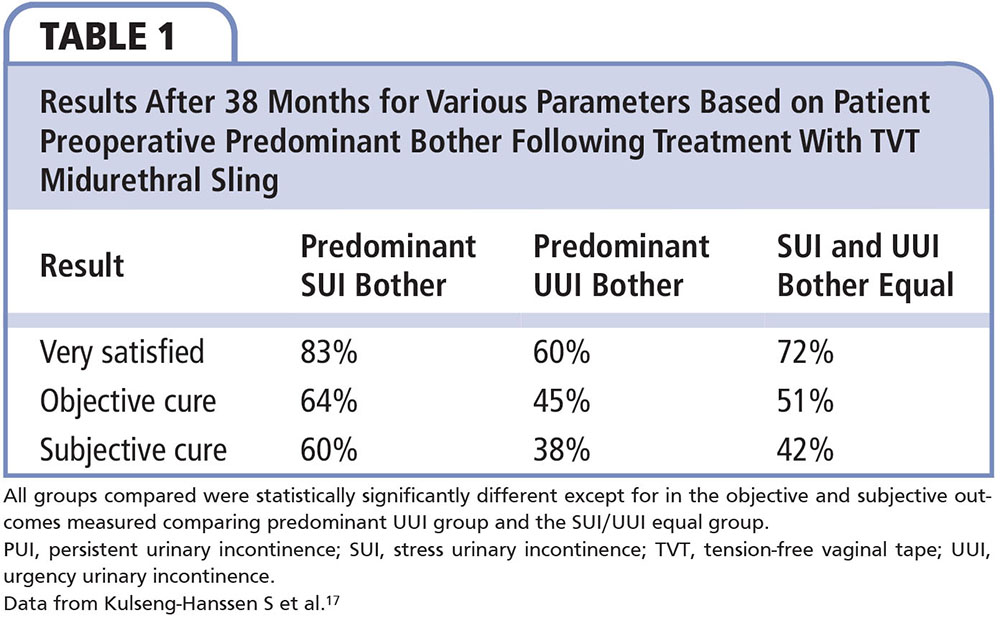

Longer-term follow-up is critical when determining the success of surgical procedures; thankfully this exists for TVT. One large study with longer follow-up classified patients based on their predominant symptom bother (predominant stress incontinence, predominant urgency incontinence, and stress and urgency equal).17 A total of 1113 patients with mixed incontinence treated with TVT with 38-month follow-up had an overall subjective cure rate of 53.8%. The subjective cure and satisfaction was highest in the stress-predominant group and lowest in the urgency-predominant group (Table 1).

Another long-term cross-sectional study looked at women with SUI and MUI who were treated with TVT.18 The data were collected by mailing patients self-reporting questionnaires. The women surveyed were between 2 and 8 years post-TVT sling surgery. The data showed that the SUI cure rate remained at approximately 85% up to 8 years postoperatively. The MUI cure rate remained at approximately 60% up to 4 years after surgery, followed by a steady decline to approximately 30% from postoperative years 4 to 8. The study concluded that the decline in continence was attributed to increasing urgency symptoms, which were also surveyed.

The TVT is a well-studied sling but multiple other MUS exist. Paick and associates19 prospectively compared MUS types in women with MUI. The study subjects all had SUI plus UUI with or without DO on preoperative UDS. The resolution rates (of SUI and UUI for TVT, suprapubic arc sling, and transobturator tape) were all similar (81.3%, 77.3%, and 78%, respectively). The study found that those with DO had a 3.4-fold risk of treatment failure. Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study, Lee and associates20 looked at women with SUI plus urge (n = 754) and SUI plus UUI (n = 517) who were treated with a retropubic or transobturator sling. The sling type was chosen based on surgeon preference. Using multivariate analysis, DO was the biggest risk factor for persistence of urgency; however, sling type was also a factor for outcomes. The transobturator approach was associated with resolution of symptoms of urgency. It has been suggested that the less compressive nature of transobturator slings may facilitate the resolution of urgency, as similar advantages have been seen for development of de novo urgency for transobturator slings over ret-ropubic slings.

One objective measure that has been examined across sling type is the resolution of DO on UDS, which is consistent with the subjective findings just described. In a series of 305 women with SUI and DO on UDS, Gamble and colleagues21 found that women treated with transobturator tape had the highest resolution of DO (47% at 3 mo). Those treated with retropubic slings and bladder neck slings were two and four times more likely to report persistent UUI, respectively. However, not all studies have found sling type to be a factor in resolutions of DO rates.22

When comparing differences across sling types, randomized trials such as the Trial of Mid-Urethral Slings (TOMUS) can be a wealthy source of data exploring treatment of SUI.23 This randomized equivalence trial of retropubic slings versus transobturator slings in women with SUI can be examined for data regarding MUI. Looking at rates of developing new UUI and the persistence of UUI were not statistically significantly different between sling types. Beyond that, it is hard to draw any meaningful conclusions about MUI. The patients included in the trial had very low urge scores at baseline, and the incidence of DO was 11% and 13% in the transobturator and retropubic sling groups, respectively.

Jain and associates24 published a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness of MUS in MUI. They found that SUI cure rates varied from 85% to 97%. The cure of urgency plus UUI varied from 30% to 85%. The overall subjective cure of patients with symptoms with or without UDS-proven MUI was 56.4% (95% CI, 45.7%-69.6%), at a mean follow-up of 34.9 months.

Looking at the available literature for the treatment of MUI, UDS is often utilized when considering invasive therapies such as slings (Figure 1). More recently, the Value of Urodynamic Evaluation (VALUE) trial25 has provided a high level of evidence with regard to the utility of UDS in SUI surgery. The VALUE trial concluded that UDS prior to anti-incontinence surgery showed no impact on treatment when compared with office evaluation only. However, caution needs to be used when the results of this noninferiority trial are generalized to the MUI patient population. The patients included in the VALUE trial had low preoperative MESA urgency incontinence scores (31.7 in the urodynamic group and 32.4 in the office evaluation group). Though it did not reach statistical significance, the evaluation-only group was less likely to have overactive bladder with incontinence when compared with the urodynamic group (34.3% vs 41.6% respectively; P = .06). The study concluded that office evaluation alone was not inferior to office evaluation with UDS with regard to success of treatment at 1 year (defined ≥ 70% improvement in Urogenital Distress Inventory score and a response of “very much better” or “much better” on Patient Global Impression of Improvement) in women with uncomplicated stress-predominant urinary incontinence. The results, the authors suggest, argue against routine preoperatively urodynamic testing in women with uncomplicated SUI. The study, no matter how strong the methodology, does not help guide the work-up or eventual management of expectations in the MUI population.

Guidelines written by professional organizations such as the American Urological Association (AUA) are another source of synthesized data regarding treatment of SUI in women with MUI. The AUA guidelines on UDS deserve attention.26 The guidelines, made prior to publication of the VALUE trial, suggest that the clinician may perform UDS in patients who are considering invasive treatments. The guidelines also suggest that clinicians consider UDS in patients with urgency incontinence when invasive treatments are considered. There is also a suggestion that UDS may be performed in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms, particularly when invasive treatments are considered. UDS could be considered if the data obtained may change treatment choices or will aid in patient counseling. This esteemed panel at the AUA, and their analysis of the literature available, suggest that overall, when patients have symptoms other than just SUI or when interventions are considered, UDS still has a role.

The AUA guidelines on the surgical treatment of stress incontinence in women also state that SUI procedures may be considered for patients with MUI and a significant stress component, and cite ample support in the literature and panel consensus.27 This conclusion should not be surprising after reviewing the myriad evidence just discussed.

Practical Advice

If patients have persistence of urgency incontinence after SUI surgery they will perceive the surgery to have failed.28-30 This highlights the importance of pre-operative counseling in patients with MUI who are going to be treated with surgery for SUI. To do this effectively, the data available need to be reviewed. In addition, it is important to understand the limitations of these data. The appropriate work-up and careful procedure selection should occur. As suggested, patients with MUI treated with MUS should be followed long term.

Clinicians must take symptoms of urgency and urgency incontinence very seriously when treating patients with procedures primarily focused on SUI. The saying, "respect the urgency,” has been used to stress the importance of these symptoms. It is essential to define the patient's treatment goals and, with these in mind, determine an appropriate treatment plan for the patient. This should include a discussion about the expected effects of the treatment and its potential complications. The treatment path for patients should be discussed in advance so they know what to expect if urgency persists, or if they remain dissatisfied with procedural results. Patients with MUI can be a challenging population to treat, and counseling should be forthright. Despite some of the potential difficulties, when appropriately selected and patient expectations are addressed, SUI surgery can be a critic tool in the armamentarium of treating MUI. ![]()

References

- Dooley Y, Lowenstein L, Kenton K, et al. Mixed incontinence is more bothersome than pure incontinence subtypes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1359-1362.

- Bump RC, Norton PA, Zinner NR, Yalcin I; Duloxetine Urinary Incontinence Study Group. Mixed urinary incontinence symptoms: urodynamic findings, incontinence severity, and treatment response. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:76-83.

- Papanicolaou S, Pons ME, Hampel C, et al. Medical resource utilisation and cost of care for women seeking treatment for urinary incontinence in an outpatient setting. Examples from three countries participating in the PURE study. Maturitas. 2005;52(suppl 2): S35-S47.

- Murray S, Lemack GE. Overactive bladder and mixed incontinence. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:385-392.

- Lee E, Nitti VW, Brucker BM. Midurethral slings for all stress incontinence: a urology perspective. Urol Clin North Am. 2012;39:299-310.

- Albo ME, Richter HE, Brubaker L, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Burch colposus-pension versus fascial sling to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2143-2155.

- Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:2-12.

- Poon CI, Zimmern PE. Is there a role for periurethral collagen injection in the management of urodynamically proven mixed urinary incontinence? Urology. 2006;67:725-729.

- Anger JT, Rodríguez LV. Mixed incontinence: stressing about urge. Curr Urol Rep. 2004;5:427-431.

- Brubaker L, Stoddard A, Richter H, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Mixed incontinence: comparing definitions in women having stress incontinence surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:268-273.

- Schrepferman CG, Griebling TL, Nygaard IE, Kreder KJ. Resolution of urge symptoms following sling cystourethropexy. J Urol. 2000;164:1628-1631.

- Kenton K, Richter H, Litman H, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Risk factors associated with urge incontinence after continence surgery. J Urol. 2009;182:2805-2809.

- Richter HE, Diokno A, Kenton K, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Predictors of treatment failure 24 months after surgery for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2008;179:1024-1030.

- Osman T. Stress incontinence surgery for patients presenting with mixed incontinence and a normal cystometrogram. BJU Int. 2003;92:964-968.

- Rezapour M, Ulmsten U. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) in women with mixed urinary incontinence— a long-term follow-up. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(suppl 2):S15-S18.

- Duckett JR, Tamilselvi A. Effect of tension-free vaginal tape in women with a urodynamic diagnosis of idiopathic detrusor overactivity and stress incontinence. BJOG. 2006;113:30-33.

- Kulseng-Hanssen S, Husby H, Schiøtz HA. Follow-up of TVT operations in 1,113 women with mixed urinary incontinence at 7 and 38 months. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:391-396.

- Holmgren C, Nilsson S, Lanner L, Hellberg D. Longterm results with tension-free vaginal tape on mixed and stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:38-43.

- Paick JS, Oh SJ, Kim SW, Ku JH. Tension-free vaginal tape, suprapubic arc sling, and transobturator tape in the treatment of mixed urinary incontinence in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:123-129.

- Lee JK, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, et al. Persistence of urgency and urge urinary incontinence in women with mixed urinary symptoms after midurethral slings: a multivariate analysis. BJOG. 2011;118:798-805.

- Gamble TL, Botros SM, Beaumont JL, et al. Predictors of persistent detrusor overactivity after transvaginal sling procedures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:696. e1-696.e7.

- Botros SM, Miller J-JR, Goldberg RP, et al. Detrusor overactivity and urge urinary incontinence following trans obturator versus midurethral slings. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:42-45.

- Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2066-2076.

- Jain P, Jirschele K, Botros SM, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of midurethral slings in mixed urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:923-932.

- Nager CW, Brubaker L, Litman HJ, et al; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. A randomized trial of urodynamic testing before stress-incontinence surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1987-1997.

- Winters JC, Dmochowski RR, Goldman HB, et al. Urodynamic studies in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188:2464-2472.

- Dmochowski RR, Blaivas JM, Gormley EA, et al. Update of AUA guideline on the surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;183:1906-1914.

- Elkadry EA, Kenton KS, FitzGerald MP, et al. Patient-selected goals: a new perspective on surgical outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1551-1557.

- Hullfish KL, Bovbjerg VE, Gibson J, Steers WD. Patient-centered goals for pelvic floor dysfunction surgery: what is success, and is it achieved? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:88-92.

- Mahajan ST, Elkadry EA, Kenton KS, et al. Patient-centered surgical outcomes: the impact of goal achievement and urge incontinence on patient satisfaction one year after surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:722-728.