Toward a Deeper Measure of Sustainability

Sustainable Materials Management offers full lifecycle assessments

Previous Article Next Article

By American Chemistry Council (ACC)

Toward a Deeper Measure of Sustainability

Sustainable Materials Management offers full lifecycle assessments

Previous Article Next Article

By American Chemistry Council (ACC)

Toward a Deeper Measure of Sustainability

Sustainable Materials Management offers full lifecycle assessments

Previous Article Next Article

By American Chemistry Council (ACC)

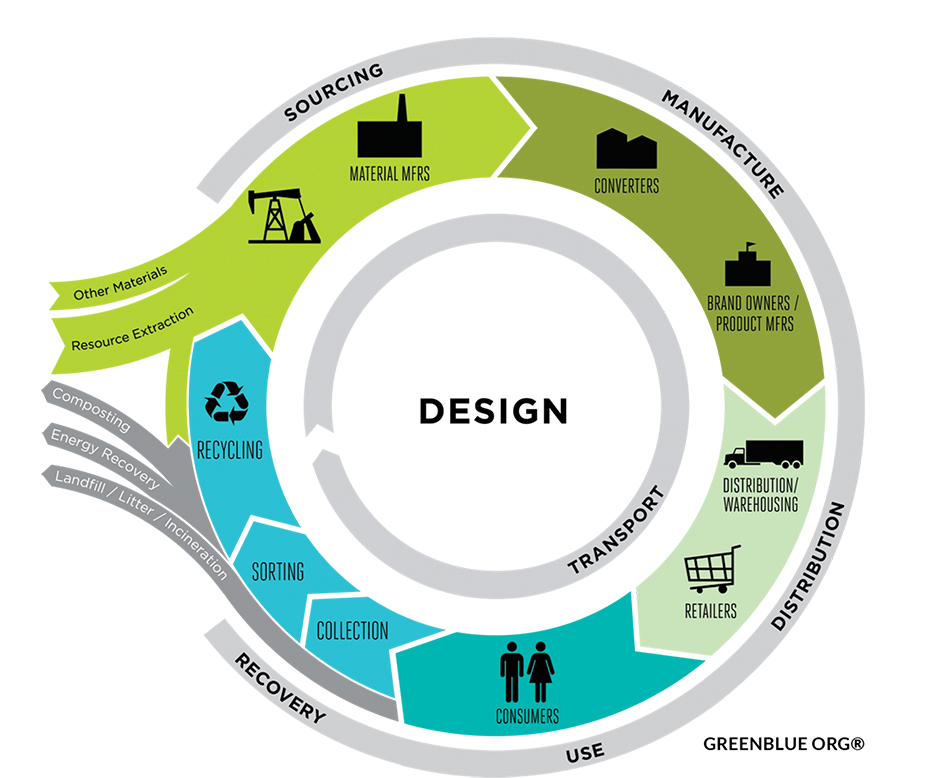

Sustainable materials management is predicated on lifecycle design, a process for identifying the positive and negative impacts of the life cycle of materials as they are produced and consumed in an economy. Used with permission from the Sustainable Packaging Coalition.

Note: This article continues the series of updates in Plastics Engineering from Plastics Make it Possible®, an initiative sponsored by America’s Plastics Makers® through the American Chemistry Council (ACC).

The concept of sustainability at times can feel a bit like a Rorschach test—people may look at the same inkblot, but they often see different things or choose to focus on certain parts.

Widespread use of the term “sustainability” is relatively new, just a couple of decades old. And while its most popular definition is widely known—meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs—in practice there are many definitions. Plus, the focus of sustainability has expanded beyond the original emphasis on the environment to include broad issues such as economic and social sustainability. And we face this give-and-take as individuals, communities, companies, nations and global actors, which makes applying sustainability principles even more complicated.

In many ways, all that’s a good thing. The push and pull of defining, refocusing and improving sustainability helps sharpen our efforts and leads to more advanced ways of looking at very complex information.

The plastics industry has been knee deep in this complex process. As plastics began replacing traditional materials, questions naturally arose about their environmental impact. So the industry has invested heavily in studying these newish materials, researching everything from energy use to safety, from biodegradability to greenhouse gas emissions, and in measuring and raising the recycling rates for used plastics.

But in the end, those are just so many data points. Without a useful paradigm or prism to provide perspective, it’s difficult to make sense of all that data.

That’s what makes the emerging consensus around an approach called Sustainable Materials Management so interesting ... and exciting for the environment. Sustainable Materials Management, or SMM, digs deep into the nature and use of materials to provide a much richer, deeper measure of environmental sustainability.

SMM looks across all the various lifecycle aspects of materials, packaging and products, from extraction to disposal. Progressive thinkers and organizations are moving toward SMM as a systemic approach to using and reusing materials more productively over their entire lifecycles. As the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency notes: “SMM represents a change in how our society thinks about the use of natural resources and environmental protection. By looking at a product’s entire lifecycle we can find new opportunities to reduce environmental impacts, conserve resources, and reduce costs.”

In short, SMM seeks to establish an overarching materials management approach to help us make more informed choices that can reduce the environmental impact of materials.

A useful way to view how SMM applies to a material or an application is to examine something specific: for example, plastic food packaging. Many people view plastic packaging as waste, noticing only the material that remains after opening a package. They likely do not see the deep analysis and considerations of improving air barriers and temperature resistance, extending shelf life, reducing cost, and other attributes that coalesce to protect the product all the way to the consumer.

Because packaging’s primary role is to deliver goods intact, packaging is not a waste. Damaged products if packaging fails—that’s a waste, of both packaging and product. In reality, packaging prevents much more waste than it creates, particularly when it comes to food. Some 90 percent of the environmental impact of growing and delivering food is related to the food—only 10 percent is related to the packaging that delivers it intact. So packaging is an investment in protecting our food—and the resources we use to produce it.

And plastic packaging can greatly extend the shelf life of food and retard spoilage, helping prevent food waste, which is the leading material going to U.S. landfills. Just a little bit of lightweight plastics can prevent a whole lot of food waste.

SMM looks at this wider view of the role of plastic packaging—reducing overall resource use and overall waste. Hopefully this approach can supplant more limited measures of sustainability, such as recycling rates. Recycling, of course, is important. Recycling can extend the life of valuable materials and reduce energy use, waste and litter, as well as cut greenhouse gas emissions. Fortunately, plastics recycling in the U.S. has been growing since measuring began in the early 1990s.

Although recycling is one aspect of sustainably managing materials, it should not be the sole measure of success. For example, because they have long lives and impact fuel economy, a heavy but more recyclable car part may not contribute to sustainability as much as a lighter but harder-to-recycle part. The real benefit of SMM is that it takes into consideration the environmental benefits of products and packaging and helps us focus on the many other sustainability issues beyond solid waste.

The previous article from Plastics Make it Possible in this publication (September 2016, Page 50) reviewed two recent studies that contribute greatly to our understanding of the environmental impacts of materials throughout the various stages of their lifecycle, a key aspect of SMM.

In 2016, the environmental firm Trucost PLC expanded on a 2014 study for the United Nations Environment Programme that looked at the total “natural capital cost” of plastics used in the consumer goods industry. The new study compared the environmental cost of using plastics in consumer products and packaging to the cost of replacing plastics with alternative materials.

Trucost found that the environmental cost of using plastics is nearly four times less than the costs of using other materials. Substituting plastics with alternatives that perform the same function is estimated to increase environmental costs from $139 billion to $533 billion annually.

These studies, and other similar studies, contribute to the application of SMM by comparing the environmental costs of various materials we use. Using the comparisons made possible by these lifecycle studies, we can make more informed decisions about the products we make and how we make them. And we can openly show the data that we used to make those decisions.

SMM will not magically cause everyone to coalesce around a fully agreed upon paradigm for environmental sustainability. There will continue to be a bit of disagreement over that same inkblot. But it does provide an approach to looking more broadly at what we’re really trying to accomplish and how to get there, while expanding and sharpening our thinking about sustainability.