Cancer Chemotherapy Update

Doxorubicin and Dacarbazine (AD) Regimen for Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Kyle E. Adkins, PharmD, BCPS*; Dominic A. Solimando, Jr, MA, FAPhA, FASHP, BCOP; and J. Aubrey Waddell, PharmD, FAPhA, BCOP

Cancer Chemotherapy Update

Doxorubicin and Dacarbazine (AD) Regimen for Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Kyle E. Adkins, PharmD, BCPS*; Dominic A. Solimando, Jr, MA, FAPhA, FASHP, BCOP; and J. Aubrey Waddell, PharmD, FAPhA, BCOP

Cancer Chemotherapy Update

Doxorubicin and Dacarbazine (AD) Regimen for Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Kyle E. Adkins, PharmD, BCPS*; Dominic A. Solimando, Jr, MA, FAPhA, FASHP, BCOP; and J. Aubrey Waddell, PharmD, FAPhA, BCOP

The complexity of cancer chemotherapy requires pharmacists be familiar with the complicated regimens and highly toxic agents used. This column reviews various issues related to preparation, dispensing, and administration of antineoplastic therapy, and the agents, both commercially available and investigational, used to treat malignant diseases. Questions or suggestions for topics should be addressed to Dominic A. Solimando, Jr, President, Oncology Pharmacy Services, Inc., 4201 Wilson Blvd #110-545, Arlington, VA 22203, e-mail: OncRxSvc@comcast.net; or J. Aubrey Waddell, Professor, University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy; Oncology Pharmacist, Pharmacy Department, Blount Memorial Hospital, 907 E. Lamar Alexander Parkway, Maryville, TN 37804, e-mail: waddfour@charter.net.

Regimen name: AD

Origin of the name: AD is an acronym for the names of the 2 medications in the regimen: doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and dacarbazine.

The complexity of cancer chemotherapy requires pharmacists be familiar with the complicated regimens and highly toxic agents used. This column reviews various issues related to preparation, dispensing, and administration of antineoplastic therapy, and the agents, both commercially available and investigational, used to treat malignant diseases. Questions or suggestions for topics should be addressed to Dominic A. Solimando, Jr, President, Oncology Pharmacy Services, Inc., 4201 Wilson Blvd #110-545, Arlington, VA 22203, e-mail: OncRxSvc@comcast.net; or J. Aubrey Waddell, Professor, University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy; Oncology Pharmacist, Pharmacy Department, Blount Memorial Hospital, 907 E. Lamar Alexander Parkway, Maryville, TN 37804, e-mail: waddfour@charter.net.

Regimen name: AD

Origin of the name: AD is an acronym for the names of the 2 medications in the regimen: doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and dacarbazine.

The complexity of cancer chemotherapy requires pharmacists be familiar with the complicated regimens and highly toxic agents used. This column reviews various issues related to preparation, dispensing, and administration of antineoplastic therapy, and the agents, both commercially available and investigational, used to treat malignant diseases. Questions or suggestions for topics should be addressed to Dominic A. Solimando, Jr, President, Oncology Pharmacy Services, Inc., 4201 Wilson Blvd #110-545, Arlington, VA 22203, e-mail: OncRxSvc@comcast.net; or J. Aubrey Waddell, Professor, University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy; Oncology Pharmacist, Pharmacy Department, Blount Memorial Hospital, 907 E. Lamar Alexander Parkway, Maryville, TN 37804, e-mail: waddfour@charter.net.

Regimen name: AD

Origin of the name: AD is an acronym for the names of the 2 medications in the regimen: doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and dacarbazine.

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(3):194–198

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5003-194

INDICATIONS

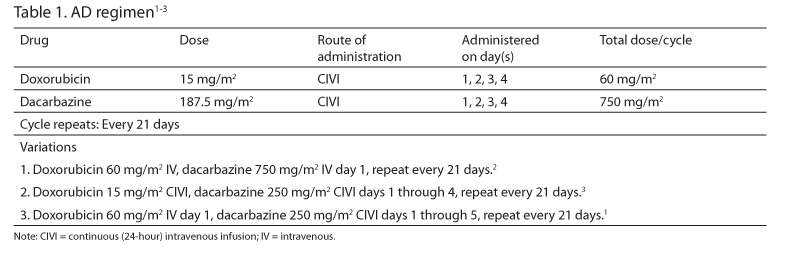

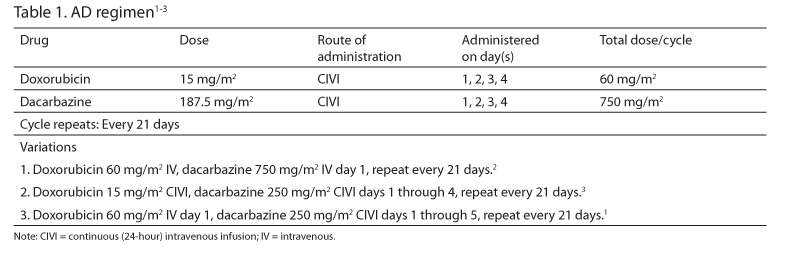

The AD regimen (Table 1) has been studied for adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy of operable soft tissue sarcoma and primary therapy of metastatic or inoperable soft tissue sarcoma.1-3 Current guidelines list it as an option for the treatment of advanced, unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent disease.4

DRUG PREPARATION

Follow institutional policies for preparation of hazardous medications when preparing and dispensing doxorubicin and dacarbazine.

A. Doxorubicin

- Use doxorubicin injection 2 mg/mL, or doxorubicin powder for injection.

- Reconstitute the powder with 0.9% sodium chloride (NS) to a concentration of 2 mg/mL.

- Dilute in 250 to 1,000 mL of NS, 5% dextrose in water (D5W), or a saline dextrose solution for continuous infusion or bolus infusion.

B. Dacarbazine

- Use dacarbazine powder for injection.

- Reconstitute with sterile water for injection, NS, or D5W to a concentration of 10 mg/mL.

- Dilute with 250 mL to 1,000 mL NS, D5W, or a saline/dextrose solution.

- Since dacarbazine is light sensitive, the solution should be protected from light immediately following preparation.5

C. Doxorubicin and dacarbazine may be mixed in the same container and administered as a single infusion.2,3,5

DRUG ADMINISTRATION

In the AD regimen, doxorubicin and dacarbazine are administered as continuous (24 hour) intravenous (IV) infusions.

SUPPORTIVE CARE

A. Acute and Delayed Emesis Prophylaxis: The AD regimen is predicted to cause acute emesis in greater than 90% of patients.6-9 The studies reviewed reported moderate or worse nausea and vomiting in 51% to 77% of patients and severe or worse nausea and vomiting in 9% to 29%.1-3 In patients receiving bolus therapy, Borden et al reported moderate or worse nausea or vomiting in 77% and severe nausea or vomiting in 29% of patients, respectively.2 Continuous infusion of AD was associated with moderate or severe nausea and vomiting in 51% versus 64% in the bolus arm in the study by Zalupski et al.3 Appropriate acute emesis prophylaxis includes a serotonin antagonist, a corticosteroid, and a neurokinin (NK1) antagonist.6-8 One of the following regimens is recommended:

- Ondansetron 16 mg to 24 mg orally (PO) and dexamethasone 12 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 1 through 4; aprepitant 125 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on day 1; and aprepitant 80 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 2 and 3.

- Granisetron 2 mg PO and dexamethasone 12 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 1 through 4; aprepitant 125 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on day 1; and aprepitant 80 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 2 and 3.

- Dolasetron 100 mg to 200 mg PO and dexamethasone 12 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 1 through 4; aprepitant 125 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on day 1; and aprepitant 80 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 2 and 3.

- Palonosetron 0.25 mg IV, given 30 minutes before AD on day 1; dexamethasone 12 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 1 through 4; aprepitant 125 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on day 1; and aprepitant 80 mg PO, given 30 minutes before AD on days 2 and 3.

The antiemetic therapy should continue for at least 3 days after the last dose of chemotherapy. A meta-analysis of several trials of serotonin antagonists recommends against prolonged (greater than 24 hours) use of these agents, making a steroid, or steroid and dopamine antagonist combination, most appropriate for follow-up therapy.10 One of the following regimens is recommended:

- Dexamethasone 4 mg PO twice a day for 3 days ± metoclopramide 0.5 to 2 mg/kg PO

every 4 to 6 hours ± diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO every 6 hours if needed for restlessness, starting on day 5 of AD. - Dexamethasone 4 mg PO twice a day for 3 days ± prochlorperazine 10 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours ± diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO every 6 hours if needed for restlessness, starting on day 5 of AD.

- Dexamethasone 4 mg PO twice a day for 3 days ± promethazine 25 to 50 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours ± diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO every 6 hours if needed, starting on day 5 of AD.

B. Breakthrough Nausea and Vomiting6-9:Patients should receive a prescription for an antiemetic to treat breakthrough nausea. One of the following regimens is recommended:

- Metoclopramide 0.5 to 2 mg/kg PO every 4 to 6 hours if needed ± diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO every 6 hours if needed for restlessness.

- Prochlorperazine 10 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours if needed ± diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO every 6 hours if needed for restlessness.

- Prochlorperazine 25 mg rectally every 4 to 6 hours if needed ± diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours if needed for -restlessness.

- Promethazine 25 to 50 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours if needed ± diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours if needed for restlessness.

Patients who do experience significant nausea or vomiting with one of these regimens should receive an agent from a different pharmacologic category.11-14 There is no evidence that substituting granisetron for ondansetron in subsequent treatment cycles, or increasing the dose, even to very high doses, is effective. This approach is not recommended.11-15

C. Hypersensitivity Precautions16-18: Doxorubicin can induce acute hypersensitivity reactions. However, such reactions are very rare and require no specific precautions. Doxorubicin may also cause a “flare reaction,” manifested by erythema, pruritis, and urticaria surrounding the injection site, or extending along the vein being infused. Although sometimes confused with an extravasation or allergic reaction, generally it is self-limiting and resolves at the end of the infusion. Additional doses of the drug can be administered without concern.16

D. Hematopoietic Growth Factors: Accepted practice guidelines and pharmaco-economic analysis suggest that an antineoplastic regimen have a greater than 20% incidence of febrile neutropenia before prophylactic use of colony stimulating factors (CSFs) is warranted. For regimens with an incidence of febrile neutropenia between 10% and 20%, use of CSFs should be considered. For regimens with an incidence of febrile neutropenia less than 10%, routine prophylactic use of CSFs is not recommended.19,20 Since febrile neutropenia was not reported in the trials of AD reviewed, prophylactic use of CSFs is not recommended.2,3,20

E. Extravasation: Doxorubicin is a potent vesicant, and extravasation should be avoided. If extravasation occurs, stop the infusion immediately and aspirate as much of the extravasated solution as possible before withdrawing the needle. The limb should be elevated and cooled intermittently (ice packs for 15 to 20 minutes 4 times a day for 3 days).21-23

MAJOR TOXICITIES

Most of the toxicities listed below are presented according to their degree of severity. Higher grades represent more severe toxicities. Although there are several grading systems for cancer chemotherapy toxicities, all are similar. One of the frequently used systems is the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (http:/ctep.info.nih.gov). Oncologists generally do not adjust doses or change therapy for grade 1 or 2 toxicities but make, or consider making, dosage reductions or therapy changes for grade 3 or 4 toxicities. Incidence values are rounded to the nearest whole percent unless incidence was less than or equal to 0.5%.

A. Cardiovascular: Decreased ejection fraction 5% to 13%,2 unspecified cardiovascular effects (severe or worse) 1%.1,3

B. Dermatologic: Mucositis, ulcers, and/or stomatitis (severe or worse) 7%3; stomatitis (with ulceration or worse) 13% to 26%2; unspecified skin and mucous membrane effects (moderate or worse) 13%,1 (severe or worse) 1%.1

C. Gastrointestinal: Nausea and vomiting (moderate or worse) 51% to 77%,1,2 (moderate or severe) 51%,3 (severe or worse) 9% to 29%.1,3

D. Hematologic: All (moderate or worse) 53%, (severe or worse) 29%1; leukopenia (severe or worse) 32% to 47%2,3;granulocytopenia (severe or worse) 16% to 38%2,3;thrombocytopenia (severe or worse) 4% to 38%.2,3

PRETREATMENT LABORATORY STUDIES NEEDED

A. Baseline

- Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT)

- Total bilirubin

- Serum creatinine

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential

- Cardiac ejection fraction

B. Prior to Each Treatment

- AST/ALT

- Total bilirubin

- Serum creatinine

- CBC with differential

C. Recommended Pretreatment Values: The minimally acceptable pretreatment CBC values required to begin a cycle with full-dose therapy in the protocols reviewed were:

- White blood cell count (WBC) greater than or equal to 3,000 cells/mcL.2

- Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) greater than 1,500 cells/mcL.2

- Platelet count greater than or equal to 100,000 cells/mcL.2,3

- Serum creatinine less than 2.5 mg/dL3, or less than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN).3

- Serum bilirubin less than 2 mg/dL,3 or less than 1.5 times the ULN.3

- AST less than 1.5 times the ULN.3

In clinical practice, a pretreatment ANC of 1,000 cells/mcL and platelets of 75,000 cells/mcL are usually considered acceptable.

DOSAGE MODIFICATION

A. Renal Function

- Dacarbazine:

a.Creatinine clearance (CrCl) 46 to 60 mL/min, reduce dose 20%.24

b.CrCl 31 to 45 mL/min, reduce dose 25%.24

c.CrCl less than or equal to 30 mL/min, reduce dose 30%.24

d.The manufacturer reports no information about dose reduction for renal dysfunction.25 - Doxorubicin:

a.No adjustment required.26

b.The manufacturer reports no information about dose reduction for renal dysfunction.27

B.Hepatic Function

- Dacarbazine: The manufacturer reports no information about dose reduction for hepatic dysfunction.25

- Doxorubicin: Total bilirubin:

a.2 to 3 times the ULN, reduce dose 25%.28

b.1.2 to 3 times the ULN and ALT/AST greater than 3 times the ULN, reduce dose 50%.28

c.Greater than 3 to 5 times the ULN, reduce dose 75%.28

d.Greater than 5 times the ULN, do not give drug.28

e.3.1 to 5 mg/dL, reduce dose 75%.27

C. Myelosuppression2,3

- WBC less than 3,000 cells/mcL or platelets less than 100,000 cells/mcL, do not give drugs.

- Restart AD when WBC is greater than or equal to 3,000 cells/mcL and platelets are greater than or equal to 100,000 cells/mcL.2,3

REFERENCES

- Borden EC, Amato DA, Rosenbaum C, et al. Randomized comparison of three Adriamycin regimens for metastatic soft tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5(6):840-850.

- Zalupski M, Metch B, Balcerzak WS, et al. Phase III comparison of doxorubicin and dacarbazine given by bolus versus infusion in patients with soft-tissue sarcomas: A Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83(13):926-932.

- Antman K, Crowley J, Balcerzak SP, et al. An intergroup phase III randomized study of doxorubicin and dacarbazine with or without ifosfamide and mesna in advanced soft tissue and bone sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(7):1276-1285.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology – Soft Tissue Sarcoma. V.2.2014. http://www.nccn.org. Accessed April 1, 2014.

- Trissel LA. Handbook on Injectable Drugs. 17thed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Phamacists; 2013:416.

- Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Grunberg SM et al. Proposal for classifying the acute emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(1):103-109.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines – Antiemesis. V.2.2014. http://www.nccn.org. Accessed April 01, 2014.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Antiemetics: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. http://www.asco.org/institute-quality/antiemetics-asco-clinical-practice-guideline-update. Accessed April 01, 2014.

- Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer. Antiemetic guidelines. 2013. http://www.mascc.org. Accessed April 1, 2014.

- Geling O, Eichler HG. Should 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonists be administered beyond 24 hours after chemotherapy to prevent delayed emesis? Systematic re-evaluation of clinical evidence and drug cost implications. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(6):1289-1294.

- Terrey JP, Aapro MS. The activity of granisetron in patients who had previously failed ondansetron antiemetic therapy. Eur J Clin Res. 1996; 8:281-288.

- Carmichael J, Keizer HJ, Cupissol D, Milliez J, Scheidel P, Schindler AE. Use of granisetron in patients refractory to previous treatment with antiemetics. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9(5):381-385.

- de Wit R, de Boer AC, vd Linden GH, Stoter G, Sparreboom A, Verweij J. Effective cross-over to granisetron after failure to ondansetron, a randomized double blind study in patients failing ondansetron plus dexamethasone during the first 24 hours following highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(8):1099-1101.

- Smith IE. A dose-finding study of granisetron, a novel antiemetic, in patients receiving cytostatic chemotherapy. The Granisetron Study Group. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1993;119(6):350-354.

- Soukop M. A dose-finding study of granisetron, a novel antiemetic, in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin. Granisetron Study Group. Support Care Cancer. 1994;2(3):

177-183. - Weiss RB. Hypersensitivity reactions. Semin Oncol. 1992;19(5):458-477.

- Zanotti KM, Markham M. Prevention and management of antineoplastic-induced hypersensitivity reactions. Drug Safety. 2001;24(10):767-779.

- Shepherd GM, Hypersensitivity reactions to chemotherapeutic drugs. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;24(3):253-262.

- Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, et al. 2006 Update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(19):3187-3205.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology - Myeloid Growth Factors. V.2.2014 http://www.nccn.org. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- Larson DL. Treatment of tissue extravasation by antitumor agents. Cancer. 1982;49(9):1796-1799.

- Larson DL. What is the appropriate management of tissue extravasation by antitumor agents? Plast Reconstr Surgery. 1985;75(3):397-402.

- Mullin S, Beckwith MC, Tyler LS. Prevention and management of antineoplastic extravasation injury. Hosp Pharm. 2000;35(1):57-74.

- Kintzel PE, Dorr RT. Anticancer drug renal toxicity and elimination: Dosing guidelines for altered renal function. Cancer Treat Rev. 1995;21(1):33-64.

- Dacarbazine [prescribing information]. Schaumburg, IL: APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2008.

- Aronoff GR, Bennett WM, Berns JS, Brier ME, Kasbekar N, Mueller BA, Pasko DA. Smoyer WE. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure. 5th ed. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2007.

- Doxorubicin [prescribing information]. New York: Pfizer Labs; 2011.

- Floyd J, Mirza I, Sachs B, Perry MC. Hepatotoxicity of chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 2006;33(1):50-67.

*Dr. Adkins is an oncology pharmacist, Hematology-Oncology Pharmacy Service, Department of Pharmacy, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland. At the time this manuscript was written, he was an Oncology Pharmacy Resident (PGY-2) at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the US Department of the Army, Department of the Navy, or Department of Defense.