Original Article

Implementation of Advanced Inventory Management Functionality in Automated Dispensing Cabinets

Russell Findlay, PharmD*; Aaron Webb, PharmD, MS*; and Jim Lund, PharmD, MS*

Original Article

Implementation of Advanced Inventory Management Functionality in Automated Dispensing Cabinets

Russell Findlay, PharmD*; Aaron Webb, PharmD, MS*; and Jim Lund, PharmD, MS*

Original Article

Implementation of Advanced Inventory Management Functionality in Automated Dispensing Cabinets

Russell Findlay, PharmD*; Aaron Webb, PharmD, MS*; and Jim Lund, PharmD, MS*

Abstract

Background: Automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) are an integral component of distribution models in pharmacy departments across the country. There are significant challenges to optimizing ADC inventory management while minimizing use of labor and capital resources. The role of enhanced inventory control functionality is not fully defined.

Objective: The aim of this project is to improve ADC inventory management by leveraging dynamic inventory standards and a low inventory alert platform.

Methods: Two interventional groups and 1 historical control were included in the study. Each intervention group consisted of 6 ADCs that tested enhanced inventory management functionality. Interventions included dynamic inventory standards and a low inventory alert messaging system. Following separate implementation of each platform, dynamic inventory and low inventory alert systems were applied concurrently to all 12 ADCs. Outcome measures included number and duration of daily stockouts, ADC inventory turns, and number of phone calls related to stockouts received by pharmacy staff.

Results: Low inventory alerts reduced both the number and duration of stockouts. Dynamic inventory standards reduced the number of daily stockouts without changing the inventory turns and duration of stockouts. No change was observed in number of calls related to stockouts made to pharmacy staff.

Conclusions: Low inventory alerts and dynamic inventory standards are feasible mechanisms to help optimize ADC inventory management while minimizing labor and capital resources.

Key Words—automated dispensing cabinets, dynamic inventory, low inventory alert, medication stockouts

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:603–608

Abstract

Background: Automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) are an integral component of distribution models in pharmacy departments across the country. There are significant challenges to optimizing ADC inventory management while minimizing use of labor and capital resources. The role of enhanced inventory control functionality is not fully defined.

Objective: The aim of this project is to improve ADC inventory management by leveraging dynamic inventory standards and a low inventory alert platform.

Methods: Two interventional groups and 1 historical control were included in the study. Each intervention group consisted of 6 ADCs that tested enhanced inventory management functionality. Interventions included dynamic inventory standards and a low inventory alert messaging system. Following separate implementation of each platform, dynamic inventory and low inventory alert systems were applied concurrently to all 12 ADCs. Outcome measures included number and duration of daily stockouts, ADC inventory turns, and number of phone calls related to stockouts received by pharmacy staff.

Results: Low inventory alerts reduced both the number and duration of stockouts. Dynamic inventory standards reduced the number of daily stockouts without changing the inventory turns and duration of stockouts. No change was observed in number of calls related to stockouts made to pharmacy staff.

Conclusions: Low inventory alerts and dynamic inventory standards are feasible mechanisms to help optimize ADC inventory management while minimizing labor and capital resources.

Key Words—automated dispensing cabinets, dynamic inventory, low inventory alert, medication stockouts

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:603–608

Abstract

Background: Automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) are an integral component of distribution models in pharmacy departments across the country. There are significant challenges to optimizing ADC inventory management while minimizing use of labor and capital resources. The role of enhanced inventory control functionality is not fully defined.

Objective: The aim of this project is to improve ADC inventory management by leveraging dynamic inventory standards and a low inventory alert platform.

Methods: Two interventional groups and 1 historical control were included in the study. Each intervention group consisted of 6 ADCs that tested enhanced inventory management functionality. Interventions included dynamic inventory standards and a low inventory alert messaging system. Following separate implementation of each platform, dynamic inventory and low inventory alert systems were applied concurrently to all 12 ADCs. Outcome measures included number and duration of daily stockouts, ADC inventory turns, and number of phone calls related to stockouts received by pharmacy staff.

Results: Low inventory alerts reduced both the number and duration of stockouts. Dynamic inventory standards reduced the number of daily stockouts without changing the inventory turns and duration of stockouts. No change was observed in number of calls related to stockouts made to pharmacy staff.

Conclusions: Low inventory alerts and dynamic inventory standards are feasible mechanisms to help optimize ADC inventory management while minimizing labor and capital resources.

Key Words—automated dispensing cabinets, dynamic inventory, low inventory alert, medication stockouts

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:603–608

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(7):603–608

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5007-603

Automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) are an integral part of medication distribution models used by pharmacy departments across the country. In a national survey conducted in 2011, -Pedersen et al1 observed that 64.5% of hospital pharmacies were using ADCs as the primary method of first-dose delivery, and 62.5% of hospitals were using ADCs as the primary method for delivering maintenance doses. Use of decentralized automated dispensing systems has been shown to improve controlled-substance inventory reconciliation processes, charge capture, first-dose turnaround time, and nursing staff satisfaction.2,3

BACKGROUND

University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics (UWHC) is a tertiary care, 592-bed academic teaching hospital that includes a freestanding 87-bed children’s hospital.3 The pharmacy department at UWHC employs a highly automated hybrid medication distribution system that dispenses nearly 70% of inpatient doses through centralized robot and carousel technologies. Controlled substance, as-needed (PRN), and emergency medications are dispensed from 62 ADCs housed in pediatric and adult inpatient units as well as in clinics and procedure areas throughout the 2 hospitals.

Standard inventory values in ADCs are static and are derived from both average dispenses per day and desired number of days of stock. At UWHC, maximum (max) and periodic automatic replenishment (PAR) standards are set to 6 days of stock and 3 days of stock, respectively, and are adjusted on an ad hoc basis. If medications fall below the predefined PAR value, they are automatically scheduled to be replenished in the next routine restocking process. In theory, because ADCs are restocked daily, medication stockouts should be eliminated by virtue of an established 3-day inventory reserve. In some cases, variable medication utilization patterns may exceed the average utilization trends and result in a medication stockout. Medication stockouts can lead to a decrease in nursing, pharmacy, and patient satisfaction; a significant disruption in pharmacy technician workflow; and a decrease in the quality of patient care by delaying medication administration.

Currently, 2 technician shifts per day are dedicated to restocking ADCs and managing issues such as medication stockouts, missing medication requests, cabinet malfunction, and user error. The ADC daily restocking process occurs each morning when cabinets send an electronic message to the central pharmacy communicating which medications have fallen below PAR level. Medications are then pulled, checked by a pharmacist, and restocked throughout the remaining part of the day. This process may take as long as 12 hours.

The baseline model presents several challenges to ADC inventory management, including a lag between the time inventory drops below the PAR level and when it is restocked in the ADC, a lean staffing model resulting from incremental increases in the number of ADCs without a commensurate increase in technician labor, and lack of a system to address trends in variable medication utilization.

To address these challenges of the current system, dynamic inventory standards and a low inventory alert messaging system were implemented and assessed.

Dynamic Inventory Standards

The dynamic inventory system automatically adjusts max and PAR inventory standards based on frequency of medication dispenses using a computer-based algorithm; the end user, however, is able to actively select desired days of stock (ie, 6 days for max and 3 days for PAR). Whereas the baseline static system at UWHC relies solely on average dispenses per day and desired number of days of stock, dynamic inventory standards derive max and PAR inventory levels from either average or peak dispenses, depending on whether utilization is categorized as consistent or variable. Medications with consistent utilization will apply average dispenses per day over a 30-day period, and medications with variable utilization apply the peak number dispensed within the last -rolling 30-day window.

Low Inventory Alert System

The low inventory alert messaging system immediately notifies pharmacy staff when inventory levels fall below an established percentage of PAR value. The alert allows ADC technicians time to restock medications in the ADC before inventory levels reach zero. The low inventory threshold is determined by the end user.

METHODS

The study protocol was received under expedited review by the UWHC institutional review board and granted exempt status because it did not constitute human subjects research. The vendor of the dynamic inventory standards and low inventory alert system assisted only in the technical aspects of implementation of each platform and played no role and exerted no influence on the study design, data collection, or data analysis.

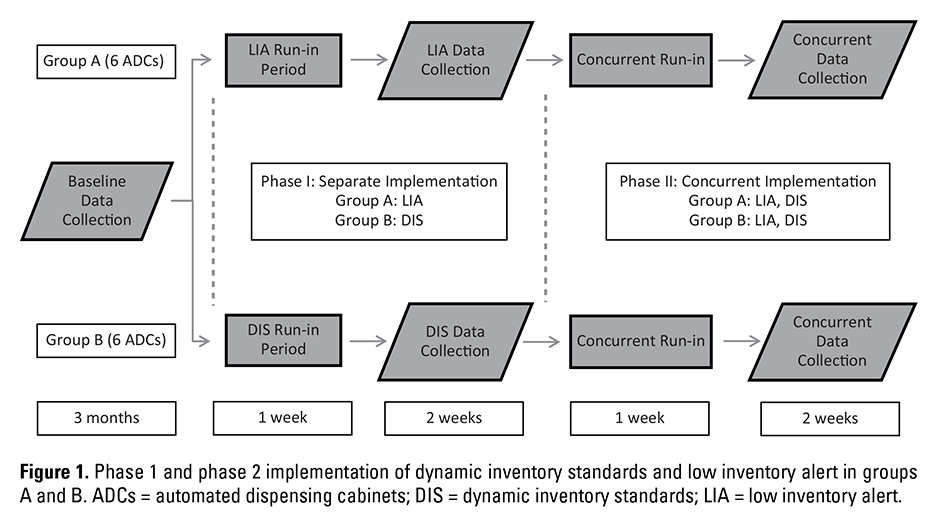

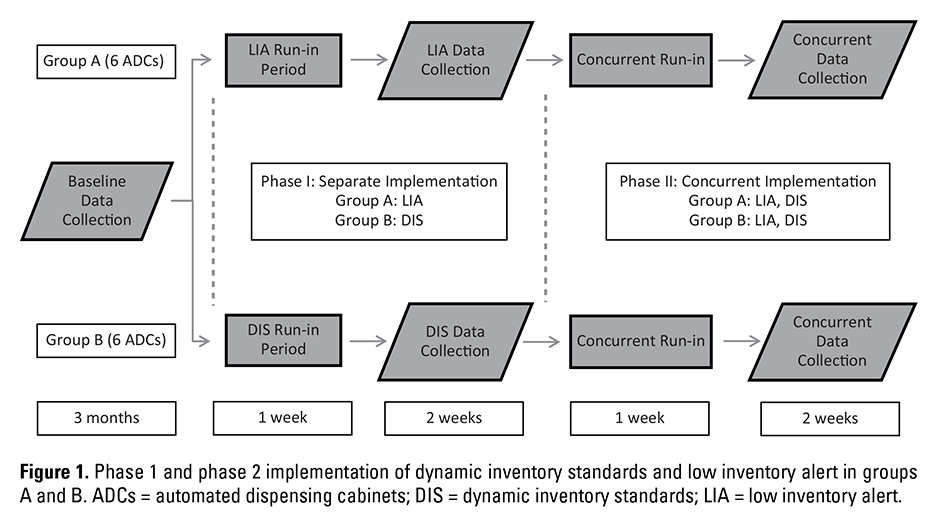

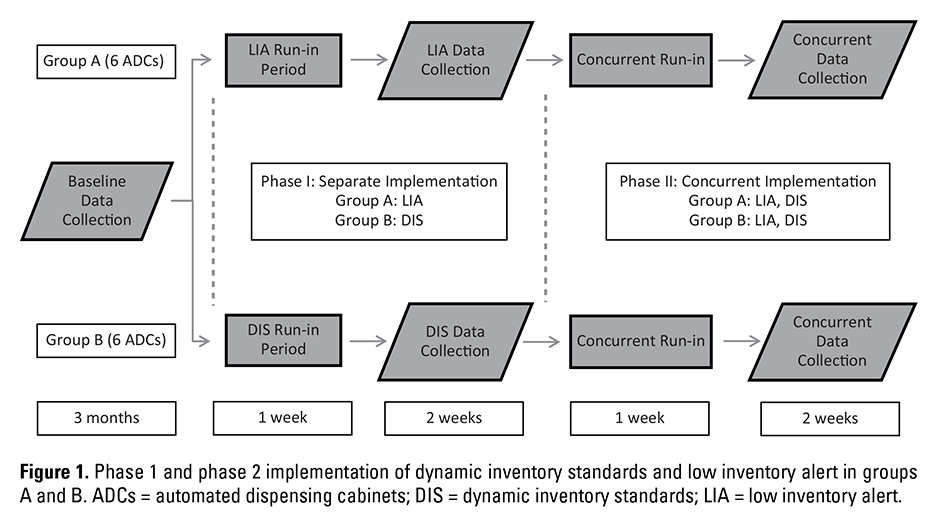

As shown in Figure 1, the design of the study included a baseline assessment over 3 months and 2 implementation phases, each with a 1-week run-in period and a 2-week data collection period. In phase 1, dynamic inventory standards and low inventory alerts were implemented separately, each in 1 group of ADCs. In group A, phase 1 implementation was low inventory alert system, and in group B, phase 1 implementation was dynamic inventory standards. In phase 2, each platform was implemented concurrently across all included ADCs.

The objectives of the study included (a) characterizing baseline ADC inventory management practices, (b) implementing inventory optimization platforms, and (c) assessing the effects of the implementation. Outcome measures included number of stockouts per day (unadjusted and adjusted per 1,000 dispenses), duration of stockouts, number of calls relating to stockouts per day to ADC technicians, and inventory turns per cabinet.

Baseline Assessment of ADC Inventory Management

Baseline number and duration of stockouts were collected using automated decision support (ADS) software. Baseline numbers of calls to ADC technicians related to medication stockouts were collected using a standardized self-report call log. Each technician was instructed on proper data collection technique. Data used in calculating inventory turns were collected using an open connectivity database (OCDB) that is interfaced with the ADS platform. Data were collected for 3 months.

Appropriate statistical tests were applied. For parametric continuous variables, a 1-sided Student t test was used, and for categorical variables, chi-square analysis was used. Nonparametric tests included the Mann-Whitney U test.

Pocket Capacity Measurements

A prerequisite for successfully implementing dynamic inventory standards is establishing pocket capacities for each line item for each ADC pocket type. Pocket capacities reflect the maximum number of medication units that can be reasonably stocked in an ADC pocket. If utilization is highly variable, the dynamic inventory system may calculate new max values that can exceed the physical capacity of the pocket. Defining physical constraints of each pocket type will help optimize the restocking process by alerting staff when requested max inventory values exceed established pocket capacities. At UWHC, 5 ADC pocket types are used. The primary investigator physically measured each ADC inventory line item (n = 648) in each of the 5 pocket types.

Several line items were excluded from dynamic inventory standards because the current static setting was deemed more appropriate: patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) keys, patient’s own supply of medications, and emergency medications (ie, diphenhydramine, glucagon, midazolam, lorazepam, dextrose, epinephrine, naloxone, and nitroglycerin).

Selection of ADCs

The included ADCs were selected based on nursing unit level of care, geography, patient census, and baseline number of daily stockouts. Intensive care unit (ICU), pediatric, clinic, and procedure area ADCs were not considered. Two groups of ADCs were selected and designated as group A and group B. Each group comprised 6 ADCs located on a medical/surgical nursing unit on the same floor of the main hospital.

Low Inventory Alert Feasibility Assessment

Snapshots of inventory event reports using an ADS platform were taken for all 62 ADCs at various times during the day over the course of a week to estimate the impact of low inventory alerts on technician workload. Assuming a low inventory alert threshold of 50%, instances of inventory levels dropping below the threshold were identified. To estimate the time required to respond to a low inventory alert, a time standard was developed by averaging response times in test runs.

Communication and Education

Town hall–style meetings were held with technical and professional staff several weeks before implementation to communicate the study’s objectives, outline expectations, and discuss potential problems in workflow. A low inventory alert users’ guide and a sheet of frequently asked questions about dynamic inventory standards were distributed. Attendance and training were tracked to ensure each employee received proper instruction.

RESULTS

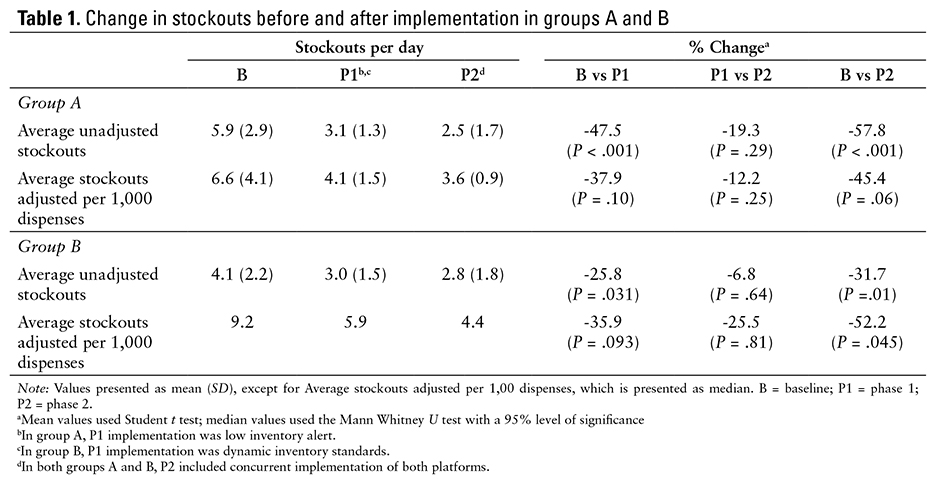

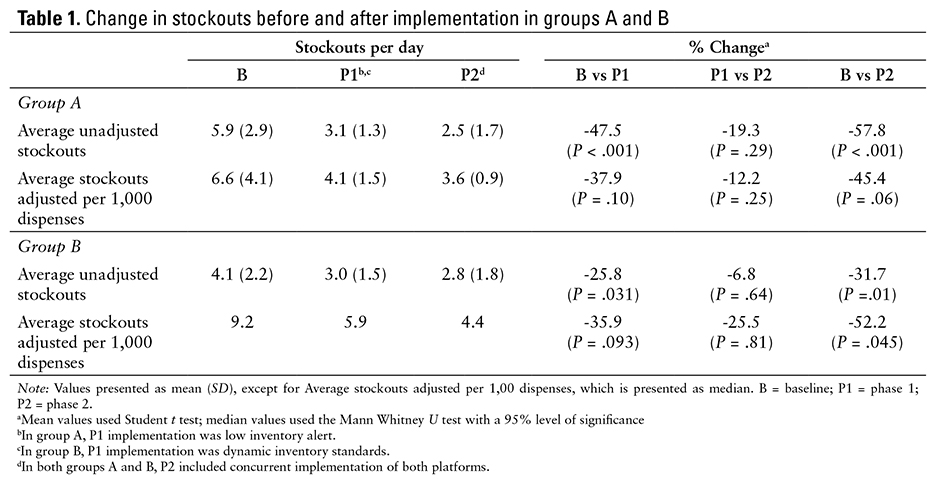

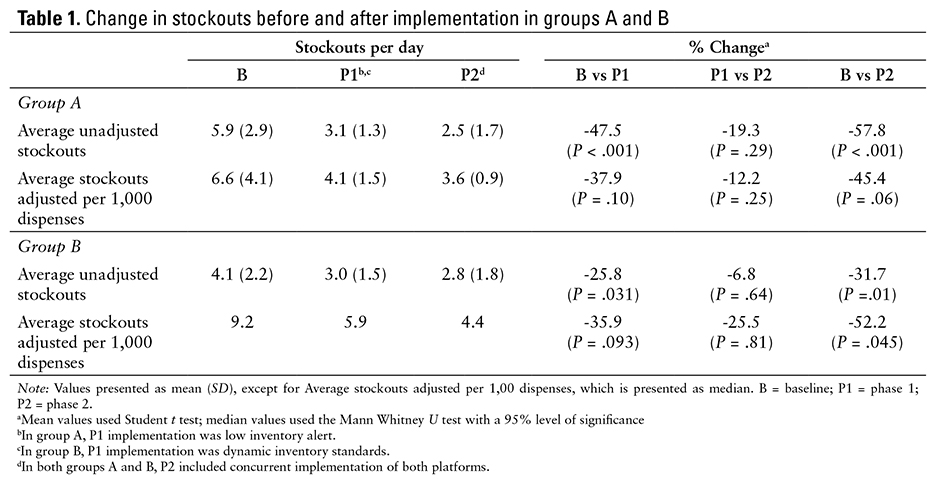

Change in the number of adjusted and unadjusted stockouts is presented in Table 1. The investigators observed baseline averages of 5.9 and 4.1 unadjusted stockouts per day in group A and group B ADCs, respectively, during phase 1. Low inventory alerts in group A decreased stockouts by 47.5% (P <.001), and dynamic inventory standards in group B reduced stockouts by 25.8% (P = .031). Compared with phase 1 results, unadjusted stockouts in group A and group B in phase 2 were reduced to 2.5 stockouts per day (-19.3%; P = .29) and 2.8 stockouts per day (-6.8%; P = .64), respectively. Total reductions were 57.8% (P < .001) in group A and 31.7% (P = .01) in group B when baseline stockouts were compared with phase 2 results.

Baseline average stockouts adjusted per 1,000 dispenses were 6.6 for group A and 9.2 for group B. After phase 1 implementation, stockouts adjusted per 1,000 dispenses in group A were 4.1 and 5.9 in group B. Median was used in group B because of nonparametric distribution. Total reductions were 45.4% (P = .06) in group A and 52.2% (P = .045) in group B following concurrent implementation compared with baseline stockouts.

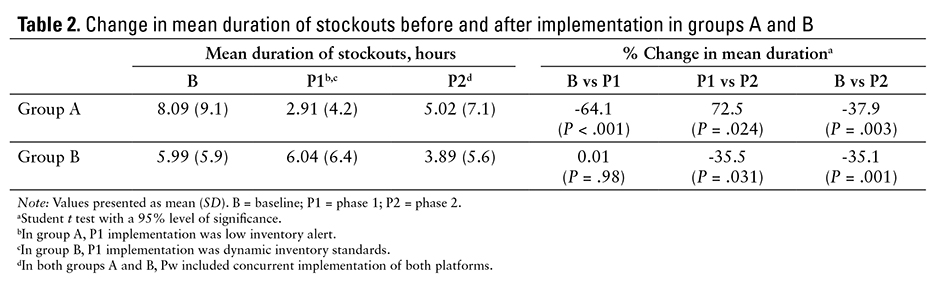

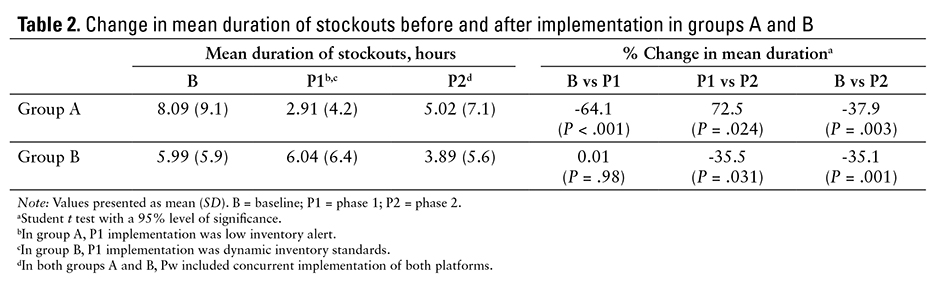

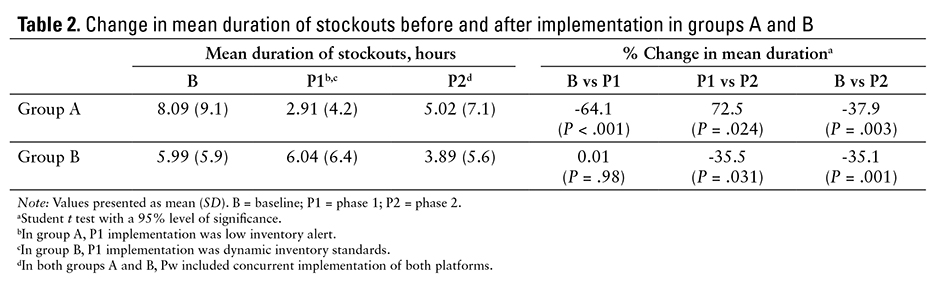

Duration of stockouts is available in Table 2. Baseline durations of stockouts were 8.09 hours in group A cabinets and 5.99 hours in group B cabinets. After phase 1, a 64.1% reduction (P < .001) was noted in group A, and no significant difference was observed in group B (0.01%; P = .98). Phase 2 results demonstrated an increase in duration of stockouts from 2.91 to 5.02 hours (72.5%; P = .024) in group A and a decrease in group B from 6.04 to 3.89 hours (35.5%; P = .031) compared with phase 1 results. Comparing baseline with phase 2 duration of stockouts resulted in a total decrease of 37.9% in group A and 35.1% in group B

(P = .003; P = .001).

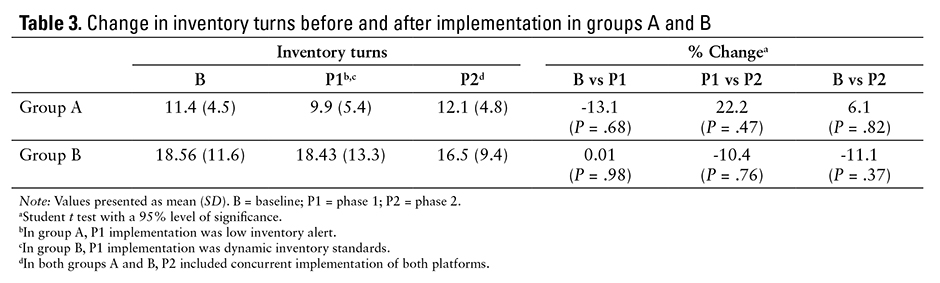

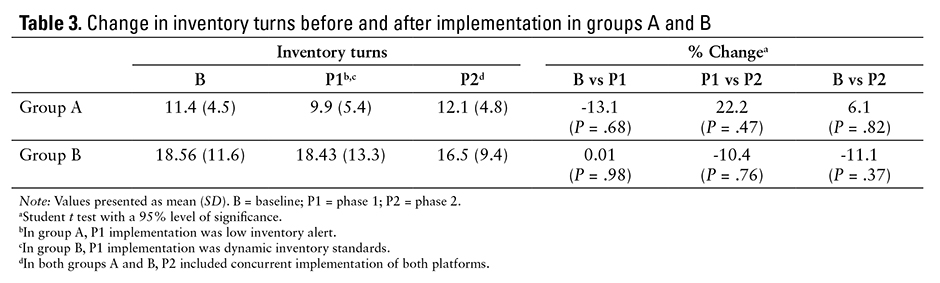

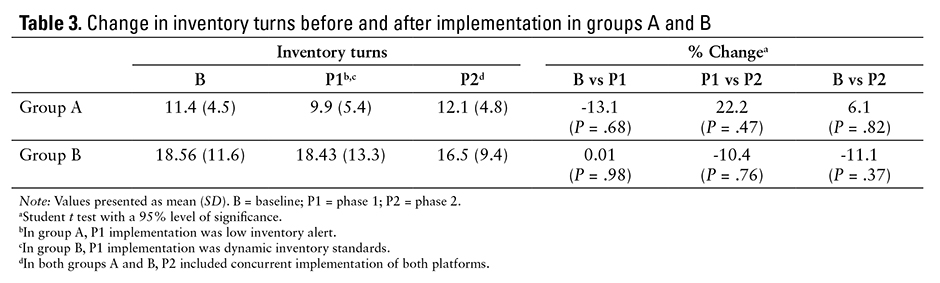

As described in Table 3, no significant changes were observed in inventory turns in either phase of the study in group B. Group A inventory turns were not reported. Similarly, no change was noted in volume of stockout-related calls made to ADC technicians in either phase.

DISCUSSION

The results of the study implementation are compelling and demonstrate statistically significant reductions in number of unadjusted stockouts. No significant incremental benefit was observed when each platform was implemented concurrently during phase 2. The universal application of both platforms trended positively, suggesting that concurrent implementation may confer at least some advantage to ADC inventory management. Similar data are not found in the published literature.

Low inventory alerts in group A dramatically reduced the duration of stockouts in phase 1; however, there were clear diminishing returns to the benefit of the low inventory alert system when the number of ADCs increased. The jump in the duration of stockouts in group A during phase 2 was attributed to doubling the number of cabinets that a fixed corps of technicians needed to restock in response to the low inventory alerts. In effect, the technician-to-cabinet ratio decreased, which had a direct impact on the technicians’ response times. The investigators presumed a priori that dynamic inventory standards do not influence the timing of medication replenishment. It was not surprising that no effect on duration of stockouts was observed.

Inventory turns were not appreciably changed by dynamic inventory standards, suggesting that stockouts were not reduced simply by overstocking the ADCs. The system’s ability to classify medication dispensing trends as consistent or variable effectively addressed the high number of stockouts without increasing on-hand value of medications.

Anecdotally, technicians who regularly work during daytime hours reported a reduction in volume of phone calls related to stockouts; however, there was no observed difference between baseline and intervention groups.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. First, the technician self-report call log likely lacked uniform compliance, particularly in the evening shift. The study has limited generalizability to ADCs located in ICUs, pediatric units, procedure areas, and clinics. Application of results to institutions with different medication distribution models should be done with caution.

Conclusion

Low inventory alerts reduced number and duration of stockouts per day with no presumed effect on inventory turns. Dynamic inventory standards reduced number of stockouts per day without increasing inventory turns and stockout duration. Low inventory alert and dynamic inventory standards are feasible mechanisms to help optimize ADC inventory without augmenting labor and capital resources. Additional benefit can be realized through concurrent implementation of both platforms.

REFERENCES

- Pedersen CA, Schneider PJ, Scheckelhoff DJ. ASHP national survey of pharmacy practice in hospital settings: Dispensing and administration—2011. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:768-785.

- Rough S, Temple J. Automation in practice: Handbook of Institutional Pharmacy Practice. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2006:329-352.

- Gray JP, Ludwig B, Temple J, Melby M, Rough S.

Comparison of a hybrid medication distribution system to simulated decentralized distribution models. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:1322-1335.

*University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Department of Pharmacy, Madison, Wisconsin. Corresponding author: Russell Findlay, PharmD, MS Candidate, University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics, Pharmacy Department, F6/133B, Mail Stop 1530, 600 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53792; e-mail: Rfindlay@uwhealth.org