Original Article

Comparison of Practice Patterns Between Inpatient

Cardiology Pharmacists With and Without Added

Qualifications in Cardiology

Jennifer Lose, PharmD, BCPS*; Michael P. Dorsch, PharmD, MS, BCPS (AQCV)†; and Robert J. DiDomenico, PharmD‡

Original Article

Comparison of Practice Patterns Between Inpatient

Cardiology Pharmacists With and Without Added

Qualifications in Cardiology

Jennifer Lose, PharmD, BCPS*; Michael P. Dorsch, PharmD, MS, BCPS (AQCV)†; and Robert J. DiDomenico, PharmD‡

Original Article

Comparison of Practice Patterns Between Inpatient

Cardiology Pharmacists With and Without Added

Qualifications in Cardiology

Jennifer Lose, PharmD, BCPS*; Michael P. Dorsch, PharmD, MS, BCPS (AQCV)†; and Robert J. DiDomenico, PharmD‡

Abstract

Background: There is a paucity of data comparing practice patterns between board-certified specialists with added qualifications in cardiology (AQCV) and cardiovascular pharmacists without these credentials.

Purpose: The purpose is to characterize differences in practice between inpatient pharmacists with and without AQCV.

Methods: We conducted a multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional, case-controlled survey. An AQCV pharmacist list was extracted from the Board of Pharmacy Specialties Web site. Hospitals with AQCV pharmacists comprised the case group. Hospitals were excluded if the AQCV pharmacists did not provide direct patient care, practiced in the outpatient setting, or were in a Veterans Affairs hospital. Each case hospital was matched to hospitals without an AQCV pharmacist in a 1:3 ratio (case:control) by region, cardiovascular discharges, and teaching hospital status. Institutions completed a survey characterizing their pharmacy services.

Results: Fifty-six hospitals completed the survey (21 AQCV, 35 non-AQCV). More AQCV pharmacists participated on rounds (100% vs 82.9%, P = .04) and devoted more time performing administrative tasks (20.5% ± 15.3% vs 11.1% ± 8.1%, P = .001) than non-AQCV pharmacists. Conversely, AQCV pharmacists spent less time providing clinical care (52.4% ± 14.5% vs 66.2% ± 19.8%, P = .007), were less involved with drug protocol management (71.4% vs 91.4%, P = .05), and performed less order verification than non-AQCV pharmacists.

Conclusions: Practice patterns differ between inpatient pharmacists with and without AQCV. Further research is needed to determine whether AQCV credentialing improves patient outcomes and to delineate what specific tasks performed by inpatient cardiology pharmacists may improve patient outcomes.

Key Words—cardiology, clinical pharmacy services, credentialing, pharmacist management

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:51–58

Abstract

Background: There is a paucity of data comparing practice patterns between board-certified specialists with added qualifications in cardiology (AQCV) and cardiovascular pharmacists without these credentials.

Purpose: The purpose is to characterize differences in practice between inpatient pharmacists with and without AQCV.

Methods: We conducted a multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional, case-controlled survey. An AQCV pharmacist list was extracted from the Board of Pharmacy Specialties Web site. Hospitals with AQCV pharmacists comprised the case group. Hospitals were excluded if the AQCV pharmacists did not provide direct patient care, practiced in the outpatient setting, or were in a Veterans Affairs hospital. Each case hospital was matched to hospitals without an AQCV pharmacist in a 1:3 ratio (case:control) by region, cardiovascular discharges, and teaching hospital status. Institutions completed a survey characterizing their pharmacy services.

Results: Fifty-six hospitals completed the survey (21 AQCV, 35 non-AQCV). More AQCV pharmacists participated on rounds (100% vs 82.9%, P = .04) and devoted more time performing administrative tasks (20.5% ± 15.3% vs 11.1% ± 8.1%, P = .001) than non-AQCV pharmacists. Conversely, AQCV pharmacists spent less time providing clinical care (52.4% ± 14.5% vs 66.2% ± 19.8%, P = .007), were less involved with drug protocol management (71.4% vs 91.4%, P = .05), and performed less order verification than non-AQCV pharmacists.

Conclusions: Practice patterns differ between inpatient pharmacists with and without AQCV. Further research is needed to determine whether AQCV credentialing improves patient outcomes and to delineate what specific tasks performed by inpatient cardiology pharmacists may improve patient outcomes.

Key Words—cardiology, clinical pharmacy services, credentialing, pharmacist management

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:51–58

Abstract

Background: There is a paucity of data comparing practice patterns between board-certified specialists with added qualifications in cardiology (AQCV) and cardiovascular pharmacists without these credentials.

Purpose: The purpose is to characterize differences in practice between inpatient pharmacists with and without AQCV.

Methods: We conducted a multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional, case-controlled survey. An AQCV pharmacist list was extracted from the Board of Pharmacy Specialties Web site. Hospitals with AQCV pharmacists comprised the case group. Hospitals were excluded if the AQCV pharmacists did not provide direct patient care, practiced in the outpatient setting, or were in a Veterans Affairs hospital. Each case hospital was matched to hospitals without an AQCV pharmacist in a 1:3 ratio (case:control) by region, cardiovascular discharges, and teaching hospital status. Institutions completed a survey characterizing their pharmacy services.

Results: Fifty-six hospitals completed the survey (21 AQCV, 35 non-AQCV). More AQCV pharmacists participated on rounds (100% vs 82.9%, P = .04) and devoted more time performing administrative tasks (20.5% ± 15.3% vs 11.1% ± 8.1%, P = .001) than non-AQCV pharmacists. Conversely, AQCV pharmacists spent less time providing clinical care (52.4% ± 14.5% vs 66.2% ± 19.8%, P = .007), were less involved with drug protocol management (71.4% vs 91.4%, P = .05), and performed less order verification than non-AQCV pharmacists.

Conclusions: Practice patterns differ between inpatient pharmacists with and without AQCV. Further research is needed to determine whether AQCV credentialing improves patient outcomes and to delineate what specific tasks performed by inpatient cardiology pharmacists may improve patient outcomes.

Key Words—cardiology, clinical pharmacy services, credentialing, pharmacist management

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:51–58

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(1):051–058

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5001-051

Many national pharmacy organizations currently endorse pharmacist specialization credentialing, similar to credentialing in other health professions, in order to meet the vision for the future of pharmacy practice and improve patient care.1-8 The American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) anticipates that the recognition of specialized pharmacists’ knowledge and skill will be important and advocates that all clinical pharmacists engaged in patient care be board certified.5,9 In addition, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) requires residency program directors of postgraduate year 2 (PGY-2) programs to be board certified, if board certification is available, in order to achieve accreditation.8

Current pharmacist credentialing is optional for pharmacists and is done primarily through the Board of Pharmacy Specialties (BPS). In addition to the 6 specialty areas of board certification (nuclear pharmacy [BCNP], pharmacotherapy [BCPS], nutrition support pharmacy [BCNSP], psychiatric pharmacy [BCPP], oncology pharmacy [BCOP], and ambulatory care pharmacy [BCACP]), BPS also designates “added qualifications” to BCPS pharmacists with “enhanced” training and experience within a specialty area, currently cardiology (AQCV) and infectious diseases (AQID).3

To obtain AQCV, BCPS pharmacists complete an application and submit a portfolio, similar to a curriculum vitae, with enhanced focus on cardiology activities. All submitted portfolios are reviewed by a portfolio review committee and assessed for whether the 5 required areas have been achieved. An examination is not taken for added qualifications certification. Recertification occurs every 7 years by the submission of an updated portfolio.

There is a significant cost to the pharmacist associated with the credentialing process.3 The initial application fee is $600 for first-time pharmacotherapy applicants. An annual certification maintenance fee of $100 is required to remain within good standing with BPS and recertification is required every 7 years at a cost of $400 by examination or BPS-approved continuing education materials. For AQCV, the initial application fee is an additional $100 with a recertification fee of $50 during renewal years. Additional costs that may also be incurred include the Pharmacotherapy Self-Assessment Program (PSAP) series for continuing education credits, the Pharmacotherapy Preparatory Course offered annually, and any travel expenses to and from the testing site.

Although pharmacy credentialing is strongly advocated by the pharmacy profession, there is a paucity of data demonstrating that board certification, including the AQCV distinction, improves patient outcomes. Critics of the board certification movement question whether the benefits justify the expenses incurred. It is assumed that credentialed pharmacists provide better patient care than noncredentialed pharmacists. However, this hypothesis has not been tested. The purpose of this study is to determine whether differences in practice exist between inpatient cardiology pharmacists with AQCV and inpatient cardiology pharmacists without the AQCV distinction.

METHODS

This is a multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional, case-controlled survey. A list of BCPS AQCV pharmacists was derived from publically available data on the BPS Web site in July 2011 for inclusion in the study (Figure 1). AQCV pharmacists were excluded if they did not provide direct patient care to acute care hospital inpatients, worked outside of the United States, or worked at a Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital. From the pharmacists meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria, 34 hospitals total were represented, forming the AQCV group. The control group was assembled by matching each case group AQCV hospital to a hospital without an AQCV pharmacist in a 3 to 1 manner. Control pharmacists were matched by geographical region, number of cardiovascular discharges, and whether or not the hospital was credentialed as a Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH) using www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov and US News Best Hospitals data (Figure 1). VA pharmacists were excluded from our analysis, as VA hospitals do not currently have 30-day mortality or readmission outcomes reported on the Hospital Compare Web site.

A survey was sent to all eligible AQCV pharmacists as well as directors of pharmacy at all matched hospitals. For hospitals with 2 or more AQCV pharmacists, the survey was only sent to one individual as the sole representative of that hospital. Survey questions addressed current practices of pharmacists providing direct care to patients in the medical cardiology area and the level of pharmacist involvement in the area of cardiology including medication policy and procedures. (Full survey questions can be found in the Appendix.) Informed consent was achieved by completion and submission of the survey. A reminder e-mail was sent to all nonresponders 2 weeks after initial contact. The study protocol was approved by the University of Michigan Health System institutional review board. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables and t test was utilized for continuous variables. All P values less than .05 were deemed statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

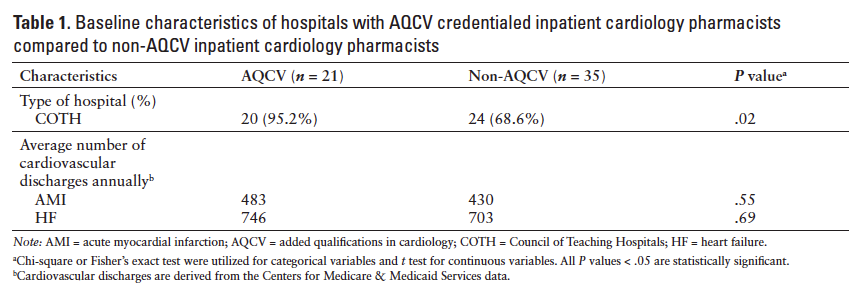

The overall response rate was 41.2%: 21 of 34 AQCV hospitals (61.7%) and 35 of 102 non-AQCV hospitals (34.3%) completed the survey. A larger proportion of hospitals in the AQCV group were teaching hospitals compared to the non-AQCV group (95.2% vs 68.8%, P = .02, respectively) (Table 1). The number of cardiovascular discharges for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and heart failure (HF) were similar between both groups. The majority of AQCV and non-AQCV pharmacists cared for both AMI and HF patients (95.2% vs 94.3%, P = 1.0, respectively). Twenty-four (68.6%) non-AQCV hospitals had BCPS pharmacists working in the inpatient cardiology areas, the remainder of non-AQCV hospitals had a noncredentialed pharmacist working in the cardiovascular area.

Practice patterns among the AQCV and non-AQCV pharmacists are compared in Table 2. Based on a 40-hour work week, AQCV pharmacists devote twice as much time performing administrative tasks (ie, meetings, Pharmacy and Therapeutics [P&T] Committee, policy and procedure development) compared to non-AQCV pharmacists but spend approximately 20% less time providing clinical care (ie, monitoring patients, assessing therapy, and optimizing pharmacotherapy). Although less time is spent by AQCV pharmacists on clinical care, all AQCV pharmacists participated in medical rounds compared to only 82.9% of non-AQCV pharmacists (P = .04). In contrast, fewer AQCV pharmacists were involved with drug protocol management (P = .05) or performed order verification (P = .002) compared to non-AQCV pharmacists. Both groups spend similar quantities of time on educational (ie, teaching students, residents, health care professionals, etc) and research activities.

A subgroup analysis compared practice patterns between AQCV pharmacists and non-AQCV pharmacists with BCPS (Table 3). Similar to the overall cohort, AQCV pharmacists spend more time performing administrative tasks and less time on both clinical care and order verification (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to demonstrate that practice patterns differ among credentialed and noncredentialed inpatient cardiology pharmacists. Differences in practice patterns were seen between AQCV and non-AQCV pharmacists in time spent in administrative and clinical tasks as well as performing order verification. These differences remained after comparing a subgroup of the non-AQCV pharmacists with BCPS to AQCV pharmacists.

Despite the advanced training and experience that is required to attain AQCV certification, we were somewhat surprised by the observation that inpatient AQCV pharmacists spend less time on direct patient care and more time performing administrative tasks compared to non-AQCV pharmacists. However, there may be plausible reasons for this observation. First, given the advanced training and experience of AQCV pharmacists, their role on hospital committees related to cardiovascular disease (eg, quality improvement committees, P&T, etc) may be more prominent and diminish the time spent on direct patient care. Second, because significantly more AQCV pharmacists practiced in teaching hospitals, they may be more likely to be involved in academic committees (eg, colleges of pharmacy or medicine) than cardiology pharmacists without AQCV. Third, AQCV pharmacists, by nature of both their training and affiliation with teaching institutions, may be more likely to participate in postdoctoral training of clinical pharmacists (eg, residency and/ or fellowship training). Not only would participation in these training programs increase administrative responsibilities (eg, serving as residency program director, completing performance evaluations, etc), but it would also increase involvement in “clinical teaching.” In this way, AQCV pharmacists may utilize their postdoctoral trainees to maintain their clinical contact while allowing time for administrative tasks. Finally, although there were no statistically significant differences observed between the 2 groups with respect to either teaching or research, AQCV pharmacists spend slightly more time participating in both teaching and research than non-AQCV pharmacists (27.1% vs 22.6%, respectively).

Similar to pharmacy credentialing, board certification for physicians is voluntary. However, in contrast to the pharmacy profession where a minority of clinical pharmacists are board certified, approximately 85% of all licensed physicians, nearly 800,000, are board certified through one of the 24 member boards (specialty and subspecialty areas) that make up the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).2 Existing data suggest that board-certified cardiologists perform better on process of care measures compared to credentialed general practitioners, but these improvements did not lead to improved clinical outcomes.10 Unlike the pharmacy profession, many medical centers and insurance companies may require physicians and other practitioners to be credentialed in order to obtain practice privileges or bill for clinical and cognitive services rendered. Consequently, the majority of these practitioners voluntarily become credentialed. If data emerge demonstrating that credentialed pharmacists improve patient care, perhaps credentialing will become a requirement to practice clinical pharmacy and also open the door to reimbursement for clinical pharmacy services. That will likely lead to higher uptake of the credentialing process by clinical pharmacists.

In a survey of directors of pharmacy at academic institutions and nonacademic institutions in the University HealthSystem Consortium and Pharmacy Systems, Inc databases, academic institutions were found to have significantly more board-certified pharmacists as compared to nonacademic institutions (26% vs 6%, P < .001, respectively).11 This was attributed to having incentives in place (94% vs 29%, P < .001) and a higher perceived value of board certification at academic institutions versus nonacademic institutions (odds ratio, 7.87; 95% CI, 1.18-52.5; P = .033), respectively. The perceived value of pharmacist board certification on an institutional and administrative level was evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale with 1 being very low value and 5 being high value. In a multivariable logistic regression model, the perceived value of board certification was found to be a strong predictor of the number of board-certified pharmacists and the availability of incentives, both reimbursement type and professional advancement type. Our results reflect these findings in that a statistically greater percentage of the AQCV group is employed by academic institutions compared to non-AQCV pharmacists. There may be a greater likelihood of academic institutions to promote pharmacist credentialing and attract board-certified pharmacists through incentives; however, our study did not specifically ascertain whether incentive programs exist at the institutions surveyed.

Compared to a 2006 national survey of non-VA hospitals, the provision of clinical pharmacy services by hospitals participating in our survey was similar to or exceeded the national average.12 More cardiology clinical pharmacists at hospitals participating in our survey appeared to provide drug information and participated in medical rounds than the national average.12 This could be representative of the increasing number of clinical pharmacy services being implemented and conducted at all hospitals across the United States over time, or this may show that both our AQCV and control hospitals have a high incidence of clinical pharmacy services compared to the entire US non-VA hospital cohort.

Despite the support for certification, there continues to be a lack of outcomes data explicitly linked to board-certified pharmacists. Previous research correlates clinical pharmacy services with decreased mortality; however, it is not known whether board-certified pharmacists improve patient outcomes.13-16 For AQCV pharmacists in particular, the requirements to obtain certification are specifically outlined and necessitate achievements in patient care, research, education, and advancement of the profession. Pharmacists meeting these requirements and achieving subsequent credentialing arguably display strong individual attributes as pharmacy practitioners. These attributes, however, may not be utilized in practice depending on the hospital environment, pharmacy workflow, and vision of a pharmacist’s role at each respective hospital. For example, order verification is not one of the 5 core clinical pharmacy services associated with favorable health outcomes, yet approximately one-half of AQCV pharmacists who responded to this survey routinely perform this task.17 In contrast, medication history taking/reconciliation and collaborative practice agreements are among the core clinical pharmacy services but were performed by a minority of respondents to this survey. Further research is needed to determine whether these differences in practice between AQCV and non-AQCV pharmacists result in differences in patient care and health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has the limitations of a survey design. Responses were assumed to be truthful and representative of the hospital practices in the medical cardiology area. It was also assumed the respondents understood the questions asked. The analysis is based on a 41.2% response rate with a higher relative response rate from AQCV than non-AQCV hospitals, thus there is the possibility of nonresponse bias. We attempted to account for this by sending a reminder e-mail 2 weeks after the initial survey. The differences seen in administrative functions could be a function of selection bias. Again, we attempted to account for this by controlling hospital characteristics; however, individual characteristics could not be precisely matched.

Conclusion

Differences exist between AQCV and non-AQCV pharmacists working in the medical cardiology area in terms of practice patterns, and this may play a role in patient outcomes. Further research should focus on determining whether AQCV improves patient outcomes and delineate what specific tasks performed by pharmacists improve outcomes in inpatient medical cardiology patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- American Bar Association. A concise guide to lawyer specialty certification. http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/2011_build/specialization/june2007_concise_guide_final.authcheckdam.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2011.

- American Board of Medical Specialties. Informational brochure. http://www.abms.org/About_ABMS/pdf/ABMS_Corp_Brochure.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2011.

- Board of Pharmacy Specialties. About BPS. http://www.bpsweb.org/about/vision.cfm. Accessed July 27, 2011.

- American College of Clinical Pharmacy. ACCP position statement: Board certification of pharmacist specialists. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(11):1146-1149.

- Blair MM, Freitag RT, Keller DL, et al; American College of Clinical Pharmacy; ACCP Certification Affairs Committee. Proposed revision to the existing specialty and specialist certification framework for pharmacy practitioners. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(2):3e-13e.

- Spinler SA, Bosso J, Hak L, et al. Report of the taskforce concerning board certification requirements for pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61(2):213-216.

- Pradel FG, Palumbo FB, Flowers L, et al. White paper: Value of specialty certification in pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:612-620.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Accreditation Standard for Postgraduate Year Two (PGY2) Pharmacy Residency Programs. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-PGY2-Standard.aspx. Accessed June 20, 2012.

- American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Board of Regents commentary qualifications of pharmacists who provide direct patient care: Perspectives on the need for residency training and board certification [published online ahead of print April 26, 2013]. Pharmacotherapy. doi: 10.1002/phar.1285.

- Chen J, Rathore S, Wang Y, et al. Physician board certification and the care and outcomes of elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:238-244.

- Smith AJ, Huke M, Rasu RS. Value of board certification in the hospital setting: A survey of academic and nonacademic medical centers. Hosp Pharm. 2010;45(5):381-388.

- Bond CA, Raehl CL. 2006 national clinical pharmacy services survey: Clinical pharmacy services, collaborative drug management, medication errors, and pharmacy technology. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(1):1-13.

- Willett MS, Bertch KE, Rich DS, et al. Prospectus on the economic value of clinical pharmacy services: A position statement of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 1989;9:45-56.

- Schumock GT, Meek PD, Ploetz PA, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services – 1988-1995. The publications committee of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16:1188-1208.

- Schumock GT, Butler MG, Meek PD, et al. Evidence of the economic benefit of clinical pharmacy services: 1996–2000. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:113–132.

- Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman JM, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2001–2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:285e–323e.

- Bond CA, Raehl CL, Patry R. Evidence-based core clinical pharmacy services in United States hospitals in 2020: Services and staffing. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:427-440.

APPENDIX

Study Survey Questions

1. Do you work in the inpatient setting?

Yes

No

2. Do you or another pharmacist you work with provide direct patient care for medical cardiology services?

a. Direct patient care = includes, but is not limited to, contributing regularly to the care of patients with cardiovascular diseases as a member of the cardiovascular interdisciplinary team by monitoring patients, assessing therapy, intervening to optimize pharmacotherapy of cardiovascular diseases, and formally educating cardiovascular disease patients and/or patient groups

b. Medical cardiology services = services containing patients being treated for, but not limited to, acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Usually the doctors taking care of these patients are cardiologists and NOT surgeons.

Yes

No

Please answer questions 3-10 from the perspective of the pharmacist who provides direct patient care for medicine cardiology patients.

3. Which of the following admitted patients do you or the pharmacist in the medical cardiology service area care for?

Heart failure

Myocardial infarction

Both

Neither

4. In a typical week, what percentage of the time does the pharmacist who provides direct patient care to medicine cardiology patients spend in the following areas? Note: The total % must total 100%.

Research

Teaching (ie, students, residents, healthcare professionals, etc.)

Clinical care (ie, monitors patients, assesses therapy, and optimizes pharmacotherapy)

Administrative functions (ie, meetings, P&T, policy and procedure development)

5. How many hours in a typical work week (40 hours) are spent doing order verification?

6. Which of the following pharmacy services are provided to patients admitted to the medical cardiology services by the pharmacist in this area? (Select all that apply)

In-service education

Drug information

Adverse drug reaction (ADR) management

Drug protocol management

Participation in medical rounds

Admission medication histories

Discharge education and/or medication reconciliation

7. Are you or one of the pharmacists in the medical cardiology services area certified through the Board of Pharmacy Specialties (BPS) as a Board Certification Pharmacotherapy Specialist (BCPS) pharmacist?

Yes

No

8. Do you or the pharmacist working in the medical cardiology services area use standardized order sets for patients with acute myocardial infarction or acute heart failure?

Yes

No

9. Do you or the pharmacist working in the medical cardiology services area use a collaborative practice agreement or protocol to prescribe post-myocardial infarction or heart failure medications?

Yes

No

*Hospital Pharmacy Services, Mayo Clinic Hospital – Rochester, Rochester, Minnesota; †Pharmacy Services and College of Pharmacy, University of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers, Ann Arbor, Michigan; ‡Department of Pharmacy Practice, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy, Chicago, Illinois. Corresponding author: Jennifer Lose, PharmD, BCPS, Mayo Clinic Hospital – Rochester, Hospital Pharmacy Services, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; phone: 507-255-2405; e-mail: lose.jennifer@mayo.edu