Original Article

Adherence to and Outcomes Associated with a Clostridium

difficile Guideline at a Large Teaching Institution

Sarah Wieczorkiewicz, PharmD, BCPS,* and RaeAnna Zatarski, PharmD*

Original Article

Adherence to and Outcomes Associated with a Clostridium

difficile Guideline at a Large Teaching Institution

Sarah Wieczorkiewicz, PharmD, BCPS,* and RaeAnna Zatarski, PharmD*

Original Article

Adherence to and Outcomes Associated with a Clostridium

difficile Guideline at a Large Teaching Institution

Sarah Wieczorkiewicz, PharmD, BCPS,* and RaeAnna Zatarski, PharmD*

Abstract

Purpose: The incidence and virulence of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) has recently increased. National CDI treatment guidelines stratify patients based on clinical symptoms and recommend treatment based on severity of illness. In 2009, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital (Park Ridge, Illinois) adopted guidelines with treatment algorithms identical to the national guidelines. The purpose of this study was to determine whether patients were being treated in accordance with the CDI guidelines and whether adherence impacted patient outcomes.

Methods: This was a retrospective, descriptive study. Subjects were identified by CDI-associated ICD-9 codes from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2011 and stratified by disease severity. Guideline adherence was assessed based on initial treatment selection, and subjects were then further categorized as undertreated (UT), overtreated (OT), or appropriately treated (AT). Secondary endpoints included need for therapy escalation, clinical cure, recurrence rates, 90-day all-cause mortality, proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and antimicrobial use.

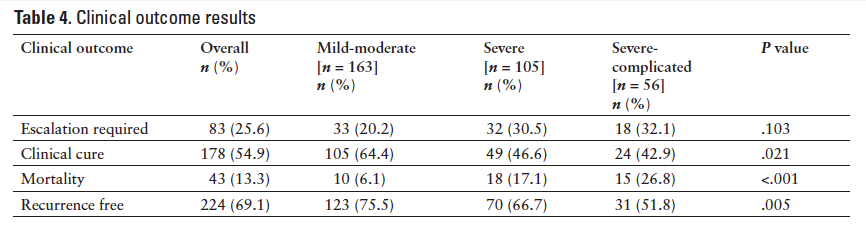

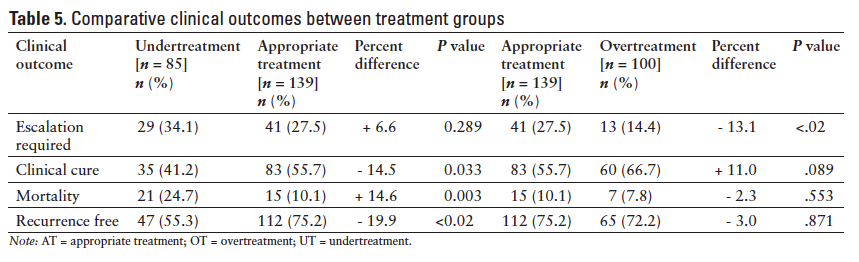

Results: Two hundred fifty subjects totaling 324 encounters were analyzed. Overall guideline adherence was 42.9%. Adherence rates by CDI severity were mild-moderate, 53.9%; severe, 39.0%; and severe-complicated, 17.9% (P < .001). Of all the subjects, 42.9% were AT, 30.9% were OT, and 26.2% were UT. Clinical outcomes between UT versus AT subjects were as follows: therapy escalation required, 34.1% versus 27.5% (P = .289); clinical cure, 41.2% versus 55.7% (P = .033); mortality, 24.7% versus 10.1% (P = .003); and recurrence, 44.7% versus 24.8% (P < .02). Clinical outcomes between AT versus OT subjects were as follows: therapy escalation required 27.5% versus 14.4% (P < .02); clinical cure, 55.7% versus 66.7% (P = .089); mortality, 10.1% versus 7.8% (P = .553); recurrence, 24.8% versus 27.8% (P = .871).

Conclusions: The majority of subjects were not treated according to CDI guidelines, particularly those with severe and severe-complicated disease. UT subjects had worse clinical outcomes and OT subjects failed to show significant improvements in clinical outcomes compared to AT subjects. Emphasis should be placed on CDI guideline adherence as this may be associated with improved outcomes.

Key Words—Clostridium difficile infection, guideline adherence, metronidazole, oral vancomycin

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:42–50

Abstract

Purpose: The incidence and virulence of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) has recently increased. National CDI treatment guidelines stratify patients based on clinical symptoms and recommend treatment based on severity of illness. In 2009, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital (Park Ridge, Illinois) adopted guidelines with treatment algorithms identical to the national guidelines. The purpose of this study was to determine whether patients were being treated in accordance with the CDI guidelines and whether adherence impacted patient outcomes.

Methods: This was a retrospective, descriptive study. Subjects were identified by CDI-associated ICD-9 codes from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2011 and stratified by disease severity. Guideline adherence was assessed based on initial treatment selection, and subjects were then further categorized as undertreated (UT), overtreated (OT), or appropriately treated (AT). Secondary endpoints included need for therapy escalation, clinical cure, recurrence rates, 90-day all-cause mortality, proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and antimicrobial use.

Results: Two hundred fifty subjects totaling 324 encounters were analyzed. Overall guideline adherence was 42.9%. Adherence rates by CDI severity were mild-moderate, 53.9%; severe, 39.0%; and severe-complicated, 17.9% (P < .001). Of all the subjects, 42.9% were AT, 30.9% were OT, and 26.2% were UT. Clinical outcomes between UT versus AT subjects were as follows: therapy escalation required, 34.1% versus 27.5% (P = .289); clinical cure, 41.2% versus 55.7% (P = .033); mortality, 24.7% versus 10.1% (P = .003); and recurrence, 44.7% versus 24.8% (P < .02). Clinical outcomes between AT versus OT subjects were as follows: therapy escalation required 27.5% versus 14.4% (P < .02); clinical cure, 55.7% versus 66.7% (P = .089); mortality, 10.1% versus 7.8% (P = .553); recurrence, 24.8% versus 27.8% (P = .871).

Conclusions: The majority of subjects were not treated according to CDI guidelines, particularly those with severe and severe-complicated disease. UT subjects had worse clinical outcomes and OT subjects failed to show significant improvements in clinical outcomes compared to AT subjects. Emphasis should be placed on CDI guideline adherence as this may be associated with improved outcomes.

Key Words—Clostridium difficile infection, guideline adherence, metronidazole, oral vancomycin

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:42–50

Abstract

Purpose: The incidence and virulence of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) has recently increased. National CDI treatment guidelines stratify patients based on clinical symptoms and recommend treatment based on severity of illness. In 2009, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital (Park Ridge, Illinois) adopted guidelines with treatment algorithms identical to the national guidelines. The purpose of this study was to determine whether patients were being treated in accordance with the CDI guidelines and whether adherence impacted patient outcomes.

Methods: This was a retrospective, descriptive study. Subjects were identified by CDI-associated ICD-9 codes from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2011 and stratified by disease severity. Guideline adherence was assessed based on initial treatment selection, and subjects were then further categorized as undertreated (UT), overtreated (OT), or appropriately treated (AT). Secondary endpoints included need for therapy escalation, clinical cure, recurrence rates, 90-day all-cause mortality, proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and antimicrobial use.

Results: Two hundred fifty subjects totaling 324 encounters were analyzed. Overall guideline adherence was 42.9%. Adherence rates by CDI severity were mild-moderate, 53.9%; severe, 39.0%; and severe-complicated, 17.9% (P < .001). Of all the subjects, 42.9% were AT, 30.9% were OT, and 26.2% were UT. Clinical outcomes between UT versus AT subjects were as follows: therapy escalation required, 34.1% versus 27.5% (P = .289); clinical cure, 41.2% versus 55.7% (P = .033); mortality, 24.7% versus 10.1% (P = .003); and recurrence, 44.7% versus 24.8% (P < .02). Clinical outcomes between AT versus OT subjects were as follows: therapy escalation required 27.5% versus 14.4% (P < .02); clinical cure, 55.7% versus 66.7% (P = .089); mortality, 10.1% versus 7.8% (P = .553); recurrence, 24.8% versus 27.8% (P = .871).

Conclusions: The majority of subjects were not treated according to CDI guidelines, particularly those with severe and severe-complicated disease. UT subjects had worse clinical outcomes and OT subjects failed to show significant improvements in clinical outcomes compared to AT subjects. Emphasis should be placed on CDI guideline adherence as this may be associated with improved outcomes.

Key Words—Clostridium difficile infection, guideline adherence, metronidazole, oral vancomycin

Hosp Pharm—2015;50:42–50

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(1):042–050

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5001-042

Clostridium difficile is a gram-positive, spore-forming, anaerobic bacillus that causes 20% to 30% of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea.1 Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) typically results from exposure to the pathogen and exposure to antimicrobials, particularly those antimicrobials with broad spectrum coverage such as third and fourth generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin.2 The longer patients are exposed to antimicrobials, the higher the risk; patients treated for longer than 3 days are twice as likely to develop CDI.3 While patients tend to exhibit symptoms of CDI after 4 to 9 days of antimicrobials, symptoms can be seen up to 8 weeks after the discontinuation of therapy. CDI has a broad range of clinical syndromes, ranging from asymptomatic carriage to mild diarrhea to life-threatening colitis.3 Aside from antimicrobial exposure, other risk factors for development of symptomatic CDI include advanced age, prolonged hospital stay, recent immunosuppressive therapy, and gastrointestinal surgery; use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has also been hypothesized as a potential risk factor.4 The diagnosis of CDI requires 2 factors: (1) the presence of diarrhea, as defined as the passage of 3 or more loose stools in a 24-hour period, and (2) a positive stool toxin assay for C. difficile toxins A and B or colonoscopic or histopathologic findings of pseudomembranous colitis.2

C. difficile first gained prominence in the late 1970s when it was found to be the primary pathogen involved in pseudomembranous colitis.3 The incidence and virulence of this pathogen has only increased since then due to the emergence of a new strain, BI/NAP1/027.1 In the United States, the annual number of patients discharged from the hospital with CDI increased from 85,700 in 1993 to 148,900 in 2003. From 2001 to 2005, the incidence doubled to 301,200 patient cases per year, bringing the 12-year total of patients discharged with CDI to over 2 million.5 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), annual incidence of CDI-related deaths had more than quadrupled from 5.7 deaths per million in 1999 to 23.7 deaths per million in 2004, with approximately 91% of those deaths occurring in patients over 65 years of age.6 A retrospective study conducted from June 2005 to May 2006 by Henrich et al found a 10.1% all-cause mortality rate among patients in all age categories with laboratory-confirmed CDI and a 15.4% all-cause mortality rate in patients over 70 years of age.7 CDIis not only a virulent infection, but a costly one as well, with annual hospital costs associated with the care of patients affected by CDI estimated at $3.2 billion nationwide.8

The significant morbidity and mortality associated with CDI means that proper diagnosis, stratification of disease severity, and treatment of persons afflicted by the disease is vital. Previously, patients with signs and symptoms of CDI and a positive toxin test were treated primarily with oral or intravenous (IV) metronidazole. Oral vancomycin was limited to those who failed metronidazole or were intolerant to its adverse effects. The rationale behind this clinical decision was determined by the comparable efficacy of metronidazole, cost of oral vancomycin, and concern for the development of vancomycin-resistant organisms such as Enterococcus.9,10 This approach of treating all patients with metronidazole has been challenged by several studies reporting an increase in metronidazole failures associated with patient factors such as albumin less than 2.5 g/dL, admission to an intensive care unit, and diabetes.11-13 In 2007, Zar et al found that oral metronidazole and oral vancomycin were equally effective in treating patients with mild-moderate CDI, whereas vancomycin was superior in those patients with severe CDI. Severe CDI was defined as the presence of 2 or more clinical factors such as albumin less than 2.5 g/dL, white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 15,000 cells/mm3, temperature greater than 38°C, or age greater than 60 years with either admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) or presence of pseudomembranous colitis automatically classified as severe.14 Considering these new data, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) published CDI treatment guidelines that recommend stratifying patients based on clinical presentation and treating based upon severity of illness.2

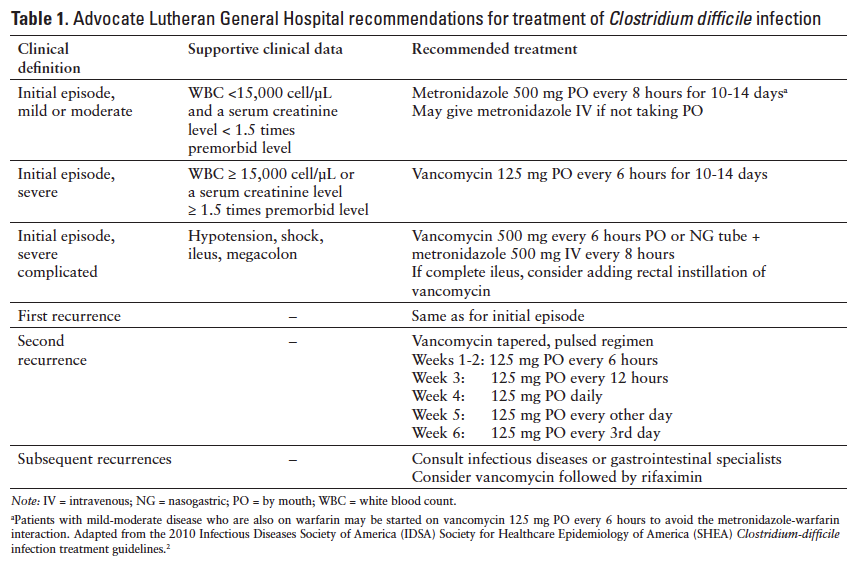

Due to anecdotal evidence suggesting wide variability in the management of patients with CDI, in March 2009, the Advocate Lutheran General Hospital’s (ALGH; Park Ridge, Illinois) Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee approved physician-managed CDI guidelines. This was in an effort to stratify patients with suspected CDI and treat according to severity to improve patient outcomes (Table 1). These guidelines reflect the SHEA/IDSA guidelines and stratify patients according to severity based on WBC count, increase in serum creatinine (SCr) from baseline, and presence of CDI complications such as hypotension, ileus, and megacolon. The physician-managed guidelines recommend limiting the use of metronidazole to mild-moderate CDI, with

vancomycin designated as the preferred agent for severe and severe-complicated CDI. The medical staff was educated on the new guidelines, which were implemented in June 2009, and pocket-sized reference cards are annually distributed. In 2010, to further enhance the diagnosis and treatment of patients affected by CDI, the hospital transitioned from using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing methodology. The latter test requires one liquid stool sample from a symptomatic patient and has been shown to demonstrate improved sensitivity and specificity when compared to ELISA (93.3% and-- 97.4% vs 73.3% and 97.6%).15,16

Despite education to the medical staff and publication of guidelines within the hospital’s electronic resources, anecdotal evidence suggested that physicians were not practicing in accordance with the guidelines (eg, patients not being treated according to severity of illness, wide variety of vancomycin dosing regimens, etc). The purpose of this study was to determine whether physicians were adhering to the CDI guidelines and whether guideline adherence had an impact on patient outcomes.

METHODS

Study Population

This was a descriptive, retrospective chart review that evaluated the prescribing patterns of physicians treating patients diagnosed with CDI. A report of electronic medical records was generated to identify subjects with an ICD-9 code for any CDI diagnosis between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2011. Subjects were then randomly selected for analysis utilizing an electronic random number generator and assignment. Subjects were included provided they were 18 years of age or older, had CDI treatment initiated at ALGH, and had a positive stool toxin assay. Subjects were excluded if they were younger than 18 years of age, had CDI treatment initiated prior to admission, or had CDI treatment discontinued after a negative stool toxin assay. This research was approved by and conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board human subjects research committee.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to determine whether patients were being treated in accordance with the CDI guidelines. Secondary endpoints included stratification of subjects with mild-moderate, severe, and severe-complicated disease; CDI guideline adherence rates among severity categories; assessment of subjects who were undertreated (UT), appropriately treated (AT), and overtreated (OT) based on initial therapy at time of diagnosis and severity category; overall incidence of the following clinical outcomes – need for therapy escalation, CDI recurrence, overall clinical cure, and 90-day all-cause mortality; comparison of clinical outcomes between the UT, AT, and OT groups; and use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and antimicrobials prior to CDI diagnosis among the severity categories.

Assessment

Subjects were categorized according to CDI severity based on their clinical signs and symptoms as detailed in the CDI guidelines (Table 1). The initial treatment regimen administered was documented for each subject, and adherence was determined based on the severity of illness at time of diagnosis. Furthermore, the treatment regimen was then deemed UT, AT, or OT based on the guideline recommendations. For example, if a subject had a WBC of 18,000 cells/µL, hypotension, and septic shock, he would be classified as severe-complicated CDI; if he received anything less than oral vancomycin 500 mg every 6 hours and IV metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours as initial treatment, he would have been deemed UT.

Definitions

AT was the exact treatment regimen recommended by the guidelines for that severity category. UT was a treatment regimen that was less than what the CDI guidelines recommended (eg, metronidazole for severe CDI). OT was a treatment regimen that was more than what the guidelines recommended (eg, IV metronidazole plus oral vancomycin for mild-moderate CDI). Clinical cure was defined as no need for therapy escalation, resolution of diarrhea by day 6, and survival through discharge. Recurrence was defined as a symptomatic patient (ie, 3 or more loose stools in a 24-hour period) with positive stool toxin assay within 90 days of initial positive. Subjects who went without a recurrence were designated as recurrence free. Reinfection was defined as a positive stool toxin assay 90 days after the initial positive. Mortality was defined as subjects who expired within 90 days of a positive stool toxin assay, regardless of the formal cause of death. Antimicrobial use was defined as the receipt of at least one dose of an antimicrobial in the 8 weeks prior to the positive stool toxin assay.

Statistical Design and Analysis

One hundred thirty subjects were required for 80% power to detect the primary endpoint of CDI guideline adherence in this descriptive study. The sample size estimate was based on investigators’ expected CDI guideline adherence proportion of 0.25, a 0.10 total width of confidence interval, power = 80%, and α = 0.05.17 Descriptive statistics for continuous (mean ± SD) and categorical [n (%)] data were calculated on all study outcomes. The analysis of between-group differences for categorical data was performed with the Pearson chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. A 2-tailed P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant for single comparisons and a P value of less than .02 was considered statistically significant for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. The Pearson correlation (r) was performed to assess the relationship between subjects’ use of PPIs and CDI incidence and antimicrobial use and CDI incidence. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

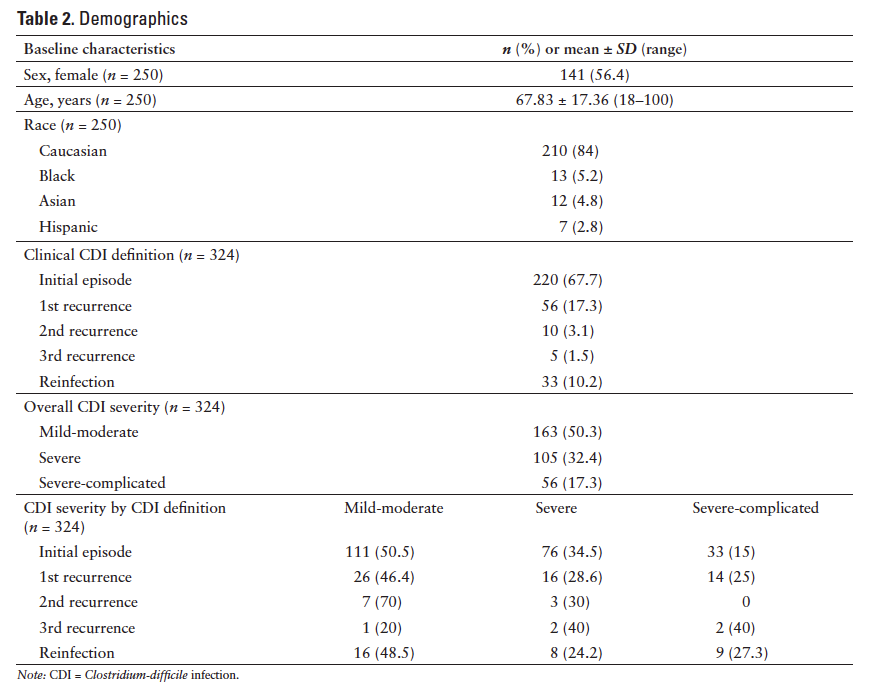

Six hundred fifty subjects were identified for primary endpoint analysis. Two hundred fifty subjects were randomly selected and their associated 324 encounters over the 2-year observation period were analyzed. The number of encounters equaled more than the number of subjects because the same subject may have had more than one CDI episode included for analysis. The subject population was predominately female (56.4%) and Caucasian (84%). The mean age was 67.83 ± 17.36 (range, 18-100) years. The majority of the encounters were initial episodes (67.7%), with a nearly equal distribution of mild-moderate CDI (50.3%) versus severe (32.4%) and severe-complicated CDI (17.3%). Baseline characteristics including the clinical definition of CDI episode observed and severity classifications of the 324 encounters are represented in Table 2.

Primary Endpoint

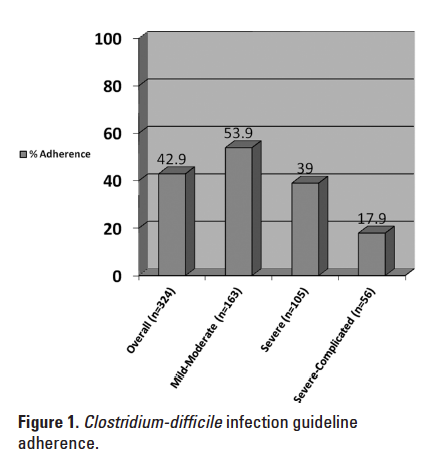

The overall CDI guideline adherence rate was 42.9%. When analyzed by CDI disease severity, adherence significantly decreased as the severity category increased (P < .001) (see Figure 1).

Secondary Endpoints

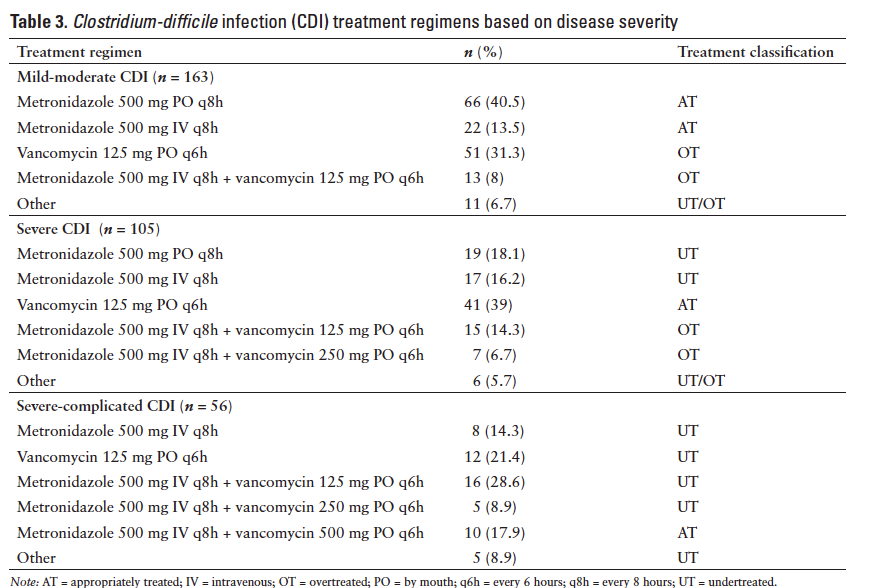

Specific treatment regimens used for each severity category are listed in Table 3. In the mild-moderate CDI group, 54% of subjects were AT, 44.8% were OT, and 1.2% were UT (2 subjects received metronidazole at a subtherapeutic dose). In the severe CDI group, 39% of subjects were AT, 35.2% were UT, and 25.7% were OT. In the severe-complicated group, 82.1% of subjects were UT and 17.9% were AT. When the 324 encounters were analyzed as whole, 42.9% of subjects were AT, 30.9% were OT, and 26.2% were UT.

The overall need for therapy escalation observed was 25.6%, clinical cure was 54.9%, 90-day all-cause mortality was 13.3%, and recurrence rate was 30.9%. When analyzed by CDI severity, there were statistically significant differences between the groups for clinical cure (P = .021), 90-day all-cause mortality (P < .001), and recurrence rate (P = .005) (Table 4). A comparison of the 4 clinical outcomes between the UT versus AT groups and OT versus AT groups is illustrated in Table 5. There was a statistically significant difference in mortality and recurrence rates between the UT versus AT groups (P < .02) and in need for therapy escalation between the AT versusOT groups (P < .02). Clinical cure was higher in the AT versus UT groups (P = .033) and in the OT versusAT groups (P = .089), although not statistically significant.

Overall, 72.5% of subjects were receiving a PPI at the time of CDI diagnosis. There was no statistical

difference between PPI use by CDI severity: mild-moderate, 71.2%; severe, 69.5%; severe-complicated, 82.1% (P = .16). Approximately 74% of subjects received at least one dose of an antimicrobial in the 8 weeks prior to CDI diagnosis. There was wide variability in the types and number of doses of antimicrobials received in the study population. There was also no statistical difference between prior antimicrobial use by CDI severity: mild-moderate, 74.7%; severe, 75.2%; severe-complicated, 69.6% (P = .81).

DISCUSSION

In this descriptive study, a 49.2% overall adherence rate to the CDI guidelines was observed, which was higher than expected. Adherence was significantly lower in the severe and severe-complicated groups compared to the mild-moderate group. This is likely due to the strict guideline adherence that was required to be considered adherent. For example, some subjects who were classified as having severe or severe-complicated CDI were unable to take oral medications. These patients were often given IV metronidazole as monotherapy rather than the recommended treatment of oral vancomycin or combination therapy for severe and severe-complicated CDI, respectively. According to the IDSA/SHEA guidelines, rectal vancomycin should be administered to those patients with an ileus, with little guidance for those unable to take oral medications.2 Out of the 324 encounters analyzed, rectal vancomycin was administered to one subject only after the appropriate treatment for severe-complicated CDI presumably failed and required therapy escalation. After discussion with specific providers, several factors were identified as limitations to the use of rectal vancomycin, including the lack of an established protocol for rectal administration of the product and difficult administration in subjects who are incontinent and require a device to contain and divert fecal matter (ie, Flexi-Seal). Duration of CDI treatment was not assessed in this study.

Additionally, there were subjects whose clinical picture fell outside the strict guideline definitions of CDI severity of illness. These patients should be critically assessed with clinical judgment guiding appropriate therapy that may be classified as nonadherent to a strict guideline. For example, neutropenic subjects may have had an overall clinical picture that was suggestive of severe CDI, but because they did not have an elevated white count or an increase of 1.5 times premorbid serum creatinine level, they were categorized as having mild-moderate CDI. If these subjects were then treated with oral vancomycin, which may be appropriate considering their overall severe clinical picture based on other factors, they were classified as nonadherent according to the CDI guidelines. This illustrates a potential limitation to the CDI treatment guidelines, as this patient population may be at higher risk of poor outcomes.

After the initial treatment regimen was assessed for guideline adherence, it was then further classified as UT, AT, and OT based on the severity of illness and the recommended therapy for that specific severity. The relatively high incidence of UT was a surprising finding; we anticipated a higher incidence of OT based on historical prescribing patterns. Subjects who were UT experienced worse outcomes than those subjects who were AT. These subjects had significantly higher recurrence rates and higher incidence of mortality; although not statistically significant, they were also less likely to achieve clinical cure. Another interesting finding was that in the severe-complicated group, subjects who received oral vancomycin 250 mg in combination with IV metronidazole had worse outcomes than those who received the recommended oral vancomycin 500 mg in combination with IV metronidazole. Conversely, subjects who were OT failed to show significant improvement in 3 of the 4 clinical outcomes as compared to those subjects who were AT. However, subjects who were AT required significantly more therapeutic escalation than the OT subjects; although not statistically significant, the OT patients had higher clinical cure rates than their AT counterparts. Subjects generally required therapy escalation when their diarrhea was not resolving as expected and occurred within 2 to 4 days on average after diagnosis (data not presented), although due to the retrospective nature of this study, it is difficult to fully ascertain the rationale in every case. The added cost of OT may be a consideration as well as the added adverse effects from additional drug exposure.

Two risk factors for the development of CDI are use of antimicrobials and/or PPIs; however, their impact on the CDI severity has not been described to our knowledge. Due to the wide variability in antimicrobial exposure in terms of number of doses as well as types of agents (ie, broad vs narrow spectrum, single vsmultiple agents, different classes, etc), no definitive conclusions could be made. However, when use of antimicrobials and PPIs prior to CDI diagnosis was compared among the 3 severity groups, use was not significantly different. This may suggest that while use of such agents is indeed a risk factor for CDI, neither had an observed association with severity of illness.

There are several limitations to this study. The study was conducted at a single center limiting the external validity; however, the guidelines utilized at ALGH are based on and reflect published guideline recommendations. Additionally, this was a retrospective evaluation that may be subject to researcher bias, as the primary endpoint relied upon the investigator’s assessment of the subject’s CDI severity category and appropriateness of treatment. This assessment and stratification of data were limited to the strict guideline treatment recommendations in terms of determining appropriateness of therapy. For example, the guidelines recommend the use of IV metronidazole and 500 mg of oral vancomycin for severe-complicated CDI, which is based upon expert opinion. For severe-complicated subjects in this study, any dose of vancomycin less than 500 mg was deemed nonadherent and an undertreatment based on the strict definitions. Based on the incidence of worse outcomes observed in the UT subjects with severe-complicated CDI, there may be an advantage of stressing the 500 mg dose of oral vancomycin for these patients; this is also reflected as expert opinion in the IDSA/SHEA guideline recommendations, but it warrants further prospective evaluation.

Moreover, there are many factors that may influence the severity of illness, clinical outcomes, and mortality associated with CDI such as age and comorbidities, which were not analyzed in this retrospective study. Thus, causative conclusions related to these outcomes cannot be made without further prospective assessment.

Several barriers to guideline adherence were identified. One barrier was simply a lack of guideline awareness among the hospital staff. Many providers did not know the guidelines existed or how to access the guidelines. Since the study, CDI guideline education through grand rounds, teaching rounds, pocket card redistribution, and the results of this specific study have been presented to house staff and other providers to stress the significance of CDI guideline adherence. The guidelines were also updated to reflect the concerns about the neutropenic patient population to ensure appropriate treatment is selected in these patients when severe or severe-complicated disease was suspected, despite the patients potentially not meeting severe or severe-complicated criteria as defined by the guidelines. Last, oral vancomycin doses other than 125 mg or 500 mg are avoided.

This retrospective, descriptive study identified that only 42.9% of subjects diagnosed with CDI were treated in accordance with the institution-approved guidelines, with slightly more subjects being OT versusUT. Failing to adhere to the guidelines may be detrimental to patients especially with regard to UT in severe and severe-complicated patients, as UT resulted in worse clinical outcomes. Further study is warranted to assess patient populations not addressed by the guidelines and potentially more aggressive initial therapy for patients with CDI to determine incidence of clinical cure, mortality, and recurrence compared to the added costs and risks of adverse effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Department of Pharmacy, the Russell Institute for Research and Innovation, and Suela Sulo, MS, for their support in all stages of this research.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Tillotson GS, Tillotson J. Clostridium difficile – a moving target. F1000 Med Rep. 2011;3:6.

- Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-455.

- Schroeder MS. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:921-928.

- Stevens V, Dumyati G, Brown J, et al. Differential risk of Clostridium difficile infection with proton pump inhibitor use by level of antibiotic exposure [published online ahead of print August 10, 2011]. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.

- Elixhauser A, Jhung MA. Clostridium difficile-associated disease in U.S. hospitals, 1993–2005. HCUP Statistical Brief #50. April 2008. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb50.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2014.

- Redelings MD, Sorvillo F, Mascola K. Increase in Clostridium difficile-related mortality rates, United States, 1999-2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1417-1419.

- Henrich TJ, Krakower D, Britton A, et al. Clinical risk factors for severe Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:415-422.

- O’Brien JA, Lahue BJ, Caro J, et al. The emerging infectious challenge of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in Massachusetts hospitals: Clinical and economic consequences. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1219-1227.

- Gerding DN, Johnson S, Peterson LR, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:459-477.

- Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Recommendations for preventing the spread of vancomycin resistance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:105-113.

- Jung KS, Park JJ, Chon YE, et al. Risk factors for treatment failure and recurrence after metronidazole treatment for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Gut Liver. 2010;4:332-337.

- Belmares J, Gerding DN, Parada JP, et al. Outcome of metronidazole therapy for Clostridium difficile disease and correlation with a scoring system. J Infect. 2007;55:495-501.

- Fernandez A, Anand G, Friedenberg F. Factors associated with failure of metronidazole in Clostridium difficile-

associated disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:414-418. - Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, et al. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:302-307.

- Lou RF, Banaei N. Is repeat PCR needed for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection? J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3738-3741.

- Peterson LR, Manson RU, Paule SM, et al. Detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile in stool samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1152-1160.

- Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. Designing Clinical Research. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

*Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Illinois. Corresponding author: Sarah M. Wieczorkiewicz, PharmD, BCPS, Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Department of Pharmacy, 1775 W. Dempster Street, Park Ridge, IL 60068; phone: 847-723-7808; fax: 847-723-2326; e-mail: sarah.wieczorkiewicz@advocatehealth.com