Original Article

Risk Factors for Bleeding in Hospitalized Patients with Elevated INR: No Vitamin K Therapy Received Versus Vitamin K Received

Monique Mounce, PharmD, BCPS*; Candace Essel, PharmD, BCPS*; Tiffany Kim, PharmD, BCPS*; and Che Matthew Harris, MD*,†

Original Article

Pharmacist Advancement of Transitions of Care to Home (PATCH) Service

Joseph Trang, PharmD*; Amanda Martinez, PharmD†; Sadaf Aslam, MD‡; and Minh-Tri Duong, PharmD§

Original Article

Pharmacist Advancement of Transitions of Care to Home (PATCH) Service

Joseph Trang, PharmD*; Amanda Martinez, PharmD†; Sadaf Aslam, MD‡; and Minh-Tri Duong, PharmD§

Abstract

Background: There is a paucity of literature on a well-defined role of a pharmacist in different aspects of transition of care service (TCS). Although health care institutions have specific details on the discharge process, there is a need for a sustainable TCS with a well-defined role of pharmacists.

Objective: To describe the impact of a pharmacist-led TCS on acute health care utilization, clinic quality indicators, and identification and resolution of medication-related problems (MRPs).

Methods: A pharmacist-managed TCS service, referred to as the Pharmacist Advancement of Transitions of Care to Home (PATCH) service, was established at an academic medical center, where high-risk patients received a postdischarge phone call from a pharmacist followed by a face-to-face meeting with the pharmacist and the patient’s primary care provider (PCP). In a prospective transitions of care group (n = 74), outcomes of patients such as acute health care utilization (an emergency department visit or an inpatient readmission, within 30 days post discharge), clinic quality indicators, and identification and resolution of MRPs were compared to a retrospective control group (n = 87) who received the standard of care.

Results: Utilization of acute health care services was significantly lower in the prospective group compared to the retrospective control group (23% vs 41.4%; P = .013). A total of 49 MRPs were discovered in patients who received the TCS. Conclusions: Pharmacists play an integral role in improving the transitions of care to reduce acute health care utilization. In addition, they may improve care transitions by optimizing clinic quality indicators and by identifying and resolving MRPs.

Key Words—medication-related problems, medication safety, pharmacist’s role, transition of care

Hosp Pharm 2015;50:994–1002

Abstract

Background: There is a paucity of literature on a well-defined role of a pharmacist in different aspects of transition of care service (TCS). Although health care institutions have specific details on the discharge process, there is a need for a sustainable TCS with a well-defined role of pharmacists.

Objective: To describe the impact of a pharmacist-led TCS on acute health care utilization, clinic quality indicators, and identification and resolution of medication-related problems (MRPs).

Methods: A pharmacist-managed TCS service, referred to as the Pharmacist Advancement of Transitions of Care to Home (PATCH) service, was established at an academic medical center, where high-risk patients received a postdischarge phone call from a pharmacist followed by a face-to-face meeting with the pharmacist and the patient’s primary care provider (PCP). In a prospective transitions of care group (n = 74), outcomes of patients such as acute health care utilization (an emergency department visit or an inpatient readmission, within 30 days post discharge), clinic quality indicators, and identification and resolution of MRPs were compared to a retrospective control group (n = 87) who received the standard of care.

Results: Utilization of acute health care services was significantly lower in the prospective group compared to the retrospective control group (23% vs 41.4%; P = .013). A total of 49 MRPs were discovered in patients who received the TCS. Conclusions: Pharmacists play an integral role in improving the transitions of care to reduce acute health care utilization. In addition, they may improve care transitions by optimizing clinic quality indicators and by identifying and resolving MRPs.

Key Words—medication-related problems, medication safety, pharmacist’s role, transition of care

Hosp Pharm 2015;50:994–1002

Abstract

Background: There is a paucity of literature on a well-defined role of a pharmacist in different aspects of transition of care service (TCS). Although health care institutions have specific details on the discharge process, there is a need for a sustainable TCS with a well-defined role of pharmacists.

Objective: To describe the impact of a pharmacist-led TCS on acute health care utilization, clinic quality indicators, and identification and resolution of medication-related problems (MRPs).

Methods: A pharmacist-managed TCS service, referred to as the Pharmacist Advancement of Transitions of Care to Home (PATCH) service, was established at an academic medical center, where high-risk patients received a postdischarge phone call from a pharmacist followed by a face-to-face meeting with the pharmacist and the patient’s primary care provider (PCP). In a prospective transitions of care group (n = 74), outcomes of patients such as acute health care utilization (an emergency department visit or an inpatient readmission, within 30 days post discharge), clinic quality indicators, and identification and resolution of MRPs were compared to a retrospective control group (n = 87) who received the standard of care.

Results: Utilization of acute health care services was significantly lower in the prospective group compared to the retrospective control group (23% vs 41.4%; P = .013). A total of 49 MRPs were discovered in patients who received the TCS. Conclusions: Pharmacists play an integral role in improving the transitions of care to reduce acute health care utilization. In addition, they may improve care transitions by optimizing clinic quality indicators and by identifying and resolving MRPs.

Key Words—medication-related problems, medication safety, pharmacist’s role, transition of care

Hosp Pharm 2015;50:994–1002

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(11):994–1002

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5011-994

A significant proportion of hospital admissions are caused by medication-related adverse events. Our current national practice does not include a reliable and accurate process for communicating medication information across layers of providers during transitions of care (TOC). As a result, care between providers is often fragmented, and treatment decisions are not always based on current and accurate information. Even though it is well known that pharmacists positively impact care transitions at defined points of care, the full potential and benefit of a pharmacist’s involvement across the complete TOC process is not well defined. There is a critical need for a pharmacist-managed TOC model, whereby a clinical pharmacist oversees a patient’s medication regimen across the continuum of care. We believe that through clinical pharmacist oversight of the high-risk patient’s medication regimen from hospital discharge to the outpatient primary care clinic setting, patient safety can be significantly improved and hospital readmission rates can be reduced. The TOC model is effective for high-risk patients with multiple chronic medications, and such a model could be reproduced, packaged, and disseminated nationally. The implications of this study are significant, as a pharmacist-led program may enable widespread dissemination of information on TOC to home in order to promote more effective and accurate ways of communicating among pharmacists, providers, and patients.

BACKGROUND

TOC, defined as the movement of a patient from one setting of care to another, such as from hospital to home, is a vulnerable period in which medication errors are prevalent.1 An estimated 20% of Medicare patients transitioning from hospital discharge to home experience adverse events after discharge, and nearly two thirds of these events are medication related.2 In 2011, 17% of all hospital stays for Medicare patients resulted in 30-day readmissions, costing $41.3 billion.3 Jencks et al found as many as 75.6% of these readmissions to be preventable.4 In addition, nearly 25% of all discharged patients presented to the emergency department within 30 days, resulting in additional costs to the health care system.5 In an effort to curb the rising costs of preventable readmissions, the Readmissions Reduction Program was put in place; this program requires the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to reduce reimbursement rates for hospitals with excessive all-cause 30-day readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), pneumonia (PNA), and myocardial infarction (MI). Other conditions recently added include acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), elective total hip arthroplasty (THA), and total knee arthroplasty (TKA).6 Another approach CMS has taken to decrease avoidable readmissions is to introduce incentives to providers in the ambulatory care setting to deliver effective transitions of care services (TCS). Providers who furnish TCS can bill at higher current procedural technology (CPT) codes, 99495 and 99496. However, to receive reimbursement, specific steps and procedures must be followed and documentation criteria must be met.7

Pharmacists have been involved with different aspects of TCS and have shown improved patient outcomes ranging from identification of medication-related problems (MRPs) to decreased readmissions.8-12 TCSs have focused on performing medication reconciliation and limited disease state management such as anticoagulation, but there is a paucity of literature on a well-defined role of a pharmacist in TCS.10 The purpose of this study was to improve on current discharge practices by implementing a pharmacist advancement of transition of care to home (PATCH) service model and to investigate the impact of this service model on acute health care utilization, identification and resolution of MRPs, and selected clinic quality indicators.

METHODS

Transition of Care Service

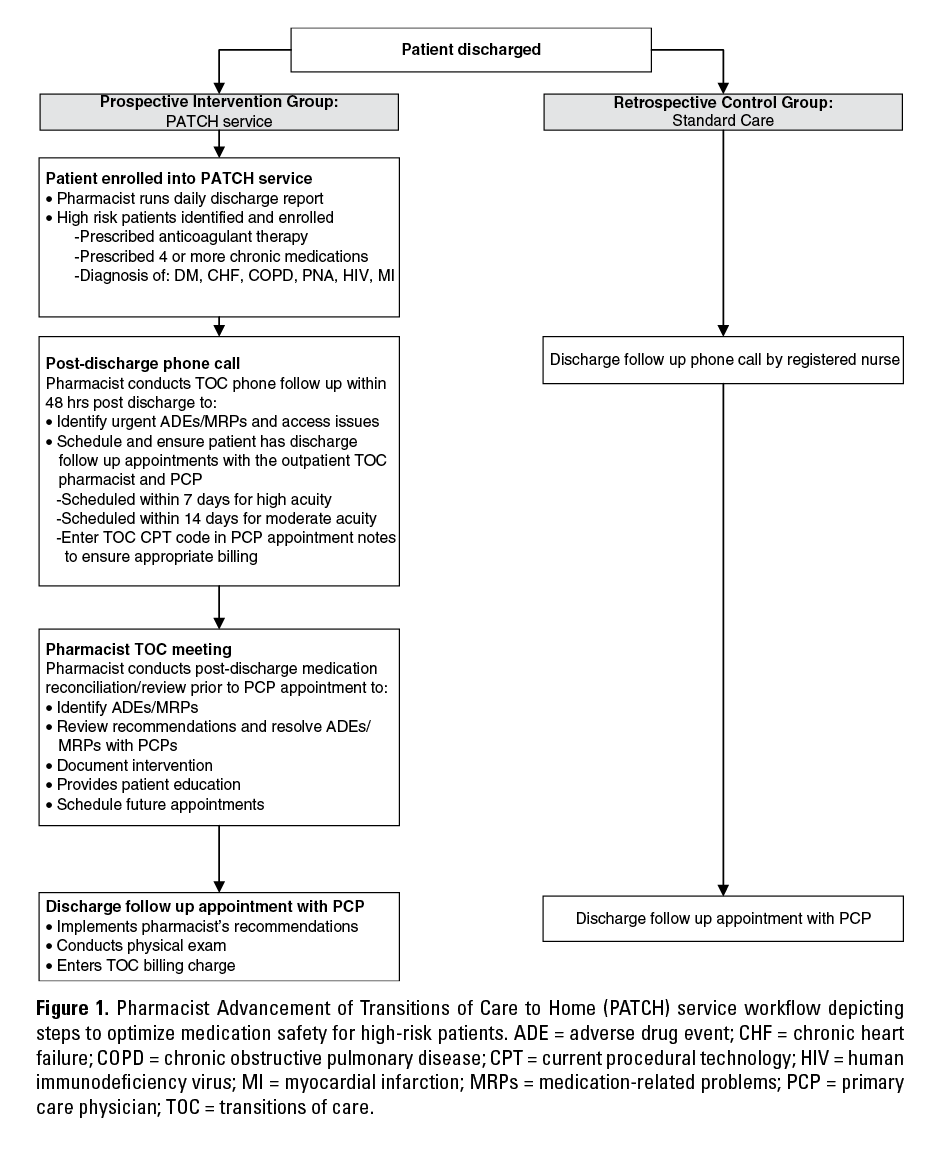

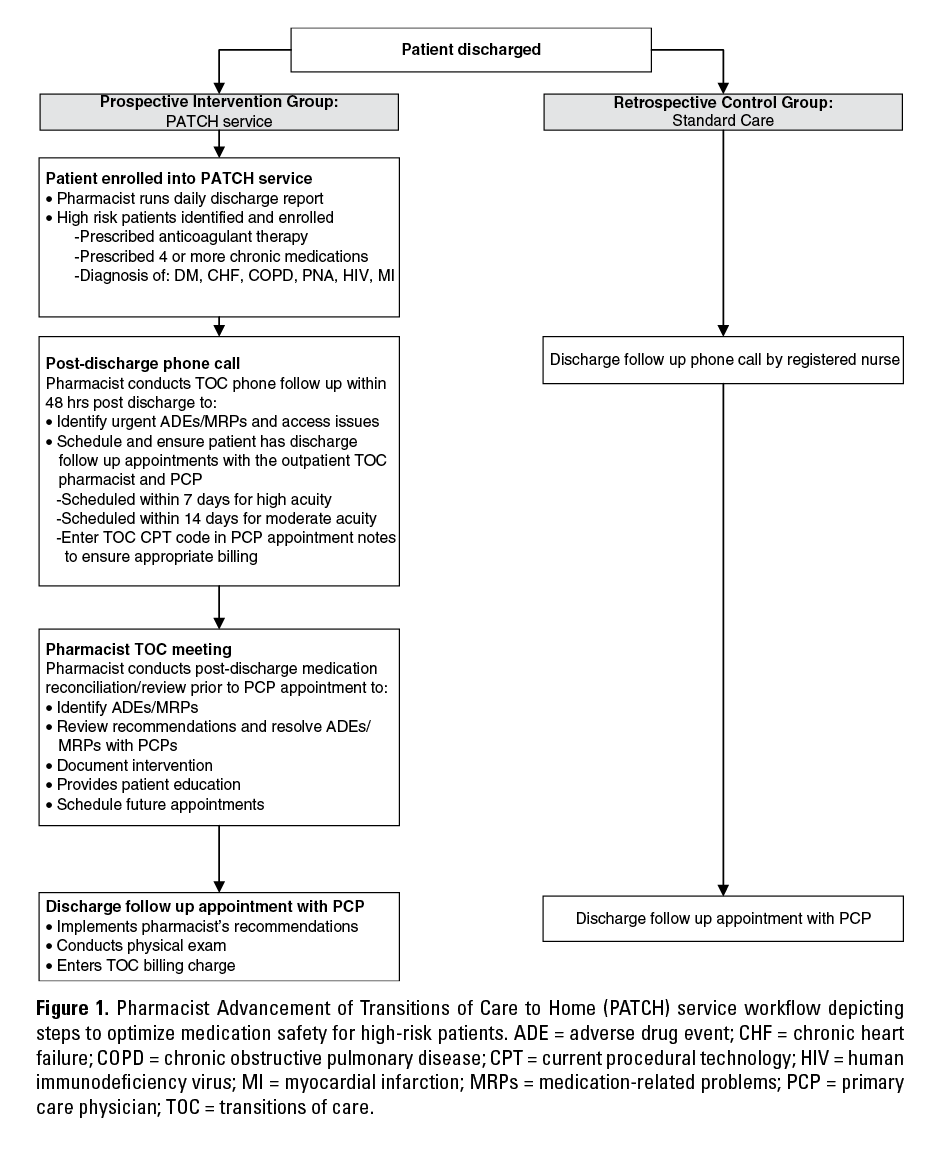

Prior to this initiative, patients at the affiliated patient-centered medical home (PCMH) did not receive formal TCS, and pharmacists were not involved in the clinic’s TCS. Standard of care consisted of an informal postdischarge phone call in which a registered nurse (RN) contacted patients who were recently discharged from the affiliated hospital solely to schedule an appointment with their primary care provider (PCP). Clinical pharmacists implemented a TCS program to assist with a comprehensive medication review, reconciliation, and patient education following hospital discharge in an effort to decrease acute health care utilization and to identify and resolve MRPs in high-risk patients. This project was reviewed by the University of South Florida’s Institutional Review Board; it was deemed as a quality initiative project and therefore was exempt from board review.

The service enrolled high-risk patients discharged from a 1,018-bed, academic medical center whose PCPs provided services at a National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)–certified level 3 PCMH. Staff at the clinic included 1 clinical pharmacist in addition to 3 PCPs, an RN care coordinator, and auxiliary staff. High-risk criteria were determined by a multidisciplinary committee. The consensus was that the PATCH service had to enroll patients who might benefit the most from prompt follow-up, including patients who had disease states being targeted by the CMS Readmissions Reduction Program and patients with disease states that might require use of many medications, especially high-risk medications such as anticoagulation or insulin.13

The service was delivered primarily by a clinical pharmacist and was also staffed by pharmacist extenders including a postgraduate year 1 (PGY1) pharmacy resident and up to 2 Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) students. The services were offered Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. until 4 p.m. The clinic shares the same electronic medical record (EMR), Epic, as the affiliated academic medical center, which stores all notes, diagnoses, and medication lists from all inpatient and outpatient encounters.

A hospital discharge report obtained from the EMR was used to identify patients who were discharged from an inpatient admission or those with an emergency department (ED) visit at the affiliated academic medical center with 1 of the 3 clinic providers listed as their PCPs. The clinical pharmacist and RN care coordinator reviewed the discharge report and patients’ charts to determine high-risk patients eligible for the TCS. Patients were considered eligible for TCS if they met at least 1 of the following high-risk criteria: discharged with 4 or more medications for chronic diseases, were prescribed oral anticoagulation therapy, and/or were diagnosed with COPD, CHF, diabetes mellitus (DM), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), MI, or PNA. Patients were excluded from receiving TCS if they were originally seen for trauma, planned surgery, or partum care. Patients ineligible for TCS received a courtesy call from the RN care coordinator to address whether they desired a follow-up visit with their PCP outside of the PATCH service.

The clinical pharmacist oriented the pharmacist extenders to the workflow of the PATCH service. The pharmacy resident and students would directly observe the clinical pharmacist during the initial postdischarge telephone call and face-to-face meeting, including the documentation process. The clinical pharmacist would then observe the pharmacist extenders performing the service until the extenders were signed off and deemed competent to support practice. Therapeutic recommendations identified by extenders were reviewed and approved by the clinical pharmacist prior to discussions with the PCP. Use of pharmacist extenders was crucial as it provided the human resources to support the patient care volume and service needs.

Identification and Resolution of MRPs

After reviewing the patients listed on the discharge report, the pharmacists conducted a chart review to identify and resolve pertinent MRPs requiring immediate intervention and to define the complexity of care, in accordance with CPT code requirements.7 MRPs were classified using the validated Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) drug-related problem classification tool V 5.01.14 The pharmacist would call the patient within 2 business days after discharge to review medication changes, identify issues with access to care, and provide patient education. Subsequently, the telephone encounter, along with urgent MRPs identified and the pharmacist’s recommendations, was routed to the patient’s PCP for review via the EMR. Patients were then scheduled for a 30-minute face-to-face TCS visit with the pharmacist followed by a 30-minute appointment with their PCP. High and moderate complexity patients had appointments scheduled within 7 and 14 calendar days after discharge, respectively. If the patients or caregivers were unavailable at the time of the phone call, a voice-mail was left asking them to contact the clinic at their earliest convenience to schedule an appointment. A follow-up phone call was then attempted the next business day.

Prior to meeting the pharmacist, updated height, weight, and blood pressure (BP) measurements were collected by a medical assistant. During the pharmacist meeting, a comprehensive medication review, BP and glucose log review, medication reconciliation, and allergy assessment were performed. Additional patient education was provided through verbal discussion and disease state management pamphlets. The pharmacist then discussed all MRPs identified with the PCP immediately after the pharmacist session and a medication plan was formulated. Recommendations were also documented within the EMR in the PCP encounter and were available for the PCP to review prior to the face-to-face visits with the patients. After the PCP visit, patients were provided with a postvisit summary sheet reinforcing educational points from both the pharmacist and PCP sessions as well as an updated medication list. Follow-up visits with the pharmacist were scheduled, if the patients required additional education and/or management based on the clinical judgment of the PCP or pharmacist. The PATCH service work flow is shown in Figure 1.

Outcomes and Analysis

To evaluate the impact of this initiative, a comparison of outcomes of all eligible patients receiving standard of care for 5 months (March 1, 2013 to July 30, 2013) to all eligible patients during the first 5 months of operation of the PATCH service (October 1, 2013 to February 15, 2014) was conducted. Standard of care practice is defined as a follow-up visit with health care providers after discharge compared to postdischarge follow-up care that includes a pharmacist’s involvement through the PATCH service.

The primary outcome was utilization of acute health care services, defined as either an ED visit or an inpatient readmission, within 30 days after discharge. This was assessed by the percentage of patients utilizing acute health care services. The secondary outcome was impact of the pharmacist-managed TCS on the number, domain, and outcome of MRPs identified in the patients who received the TCS. MRPs were collected according to the validated PCNE MRP classification tool. In addition, selected clinic quality indicators were evaluated by measuring overall changes in average fasting blood glucose (FBG) and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) up to 30 days after discharge. We chose these parameters because the preexisting clinic population had a substantial number of patients with hypertension and DM. These measures are also easily attained and monitored through lab draws or patient self-reported logs.

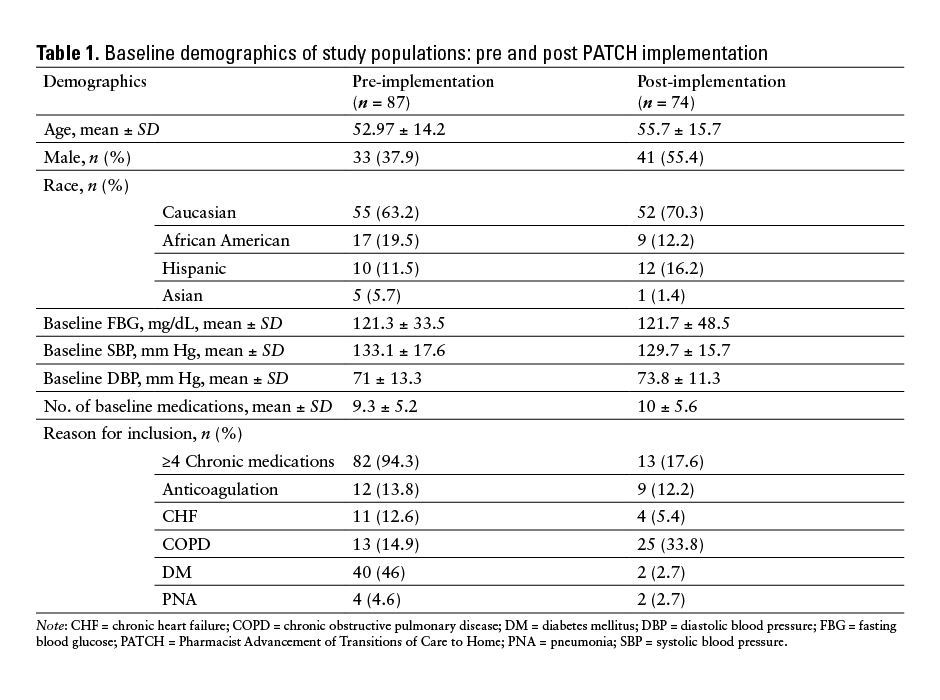

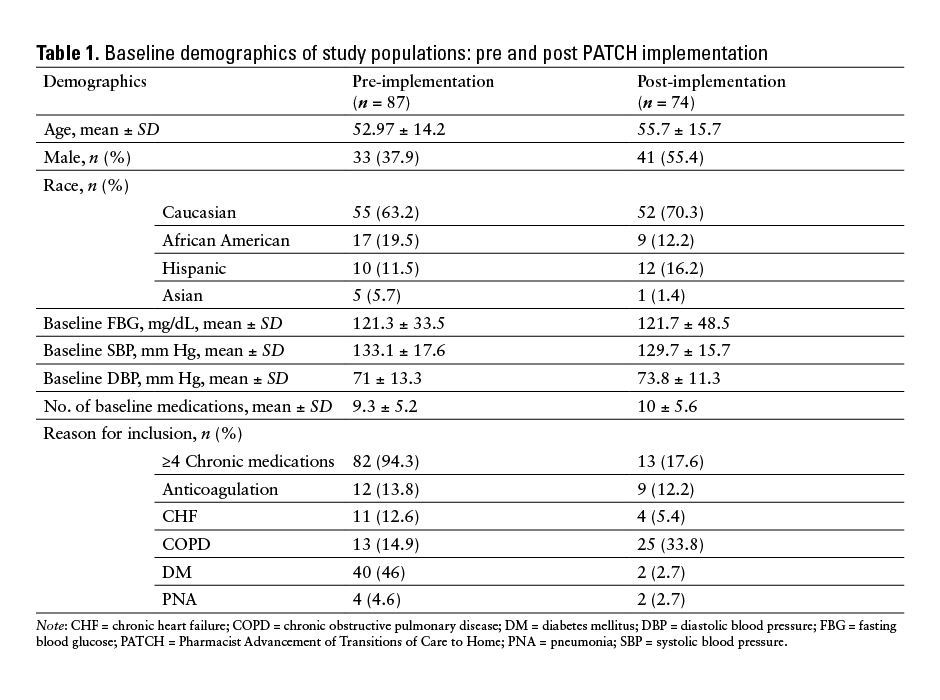

Baseline characteristics were collected for each group (Table 1), including age, gender, race, number of baseline medications, baseline FBG, SBP, and DBP, and reason for inclusion. Baseline FBG, SBP, and DBP were defined as the most recently documented values prior to hospital discharge or ED visit.

To determine the significance between 2 groups, we conducted chi-square and unpaired 2-tailed Student t tests for nominal and continuous data, respectively. Statistical significance was established using an alpha of 0.05. The analyses for the primary and secondary outcomes were performed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which was defined as all patients who were eligible for TCS in the prospective and retrospective groups.

RESULTS

A total of 362 patient’s charts were reviewed. One hundred and eighty-two charts were reviewed during the retrospective period, and 87 patients were included based on the inclusion criteria for the TCS. During the prospective phase, 180 patients were discharged from the hospital or ED; of these, 74 patients were deemed eligible for TCS. Thirty (41%) patients received the TCS, whereas 44 (59%) were unable to receive complete TCS due to the unavailability of the patient or provider. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups (Table 1).

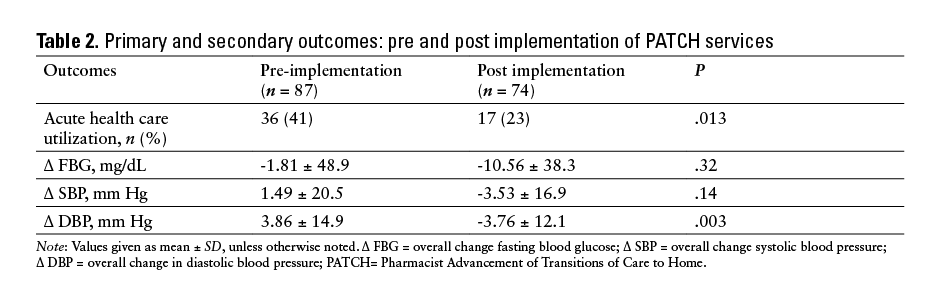

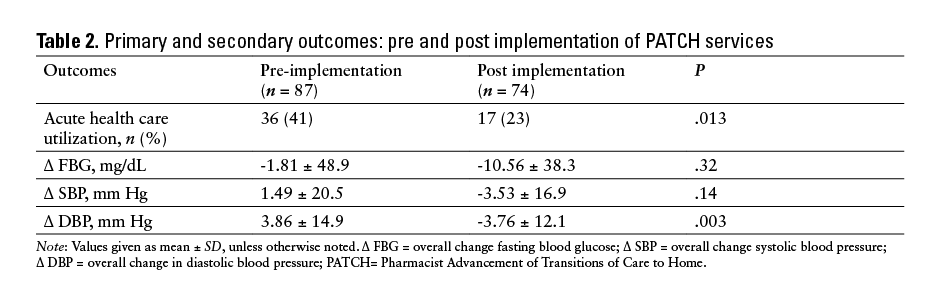

Utilization of acute health care services within 30 days was significantly lower in the prospective group compared to the retrospective group (23% vs 41.4%, respectively; P = .013).

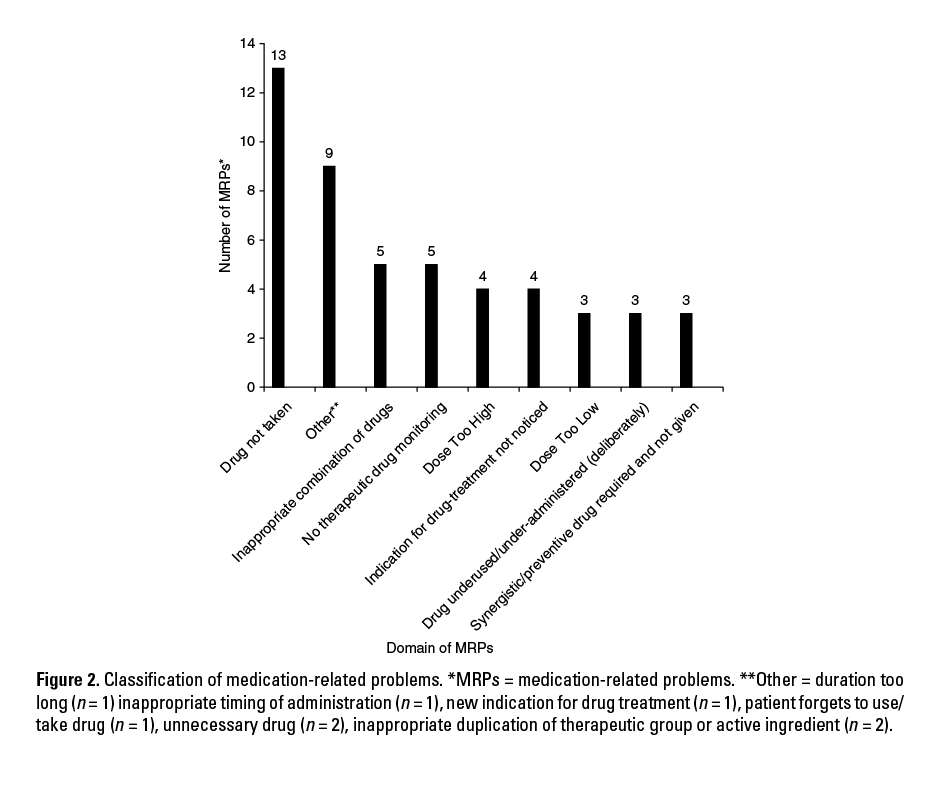

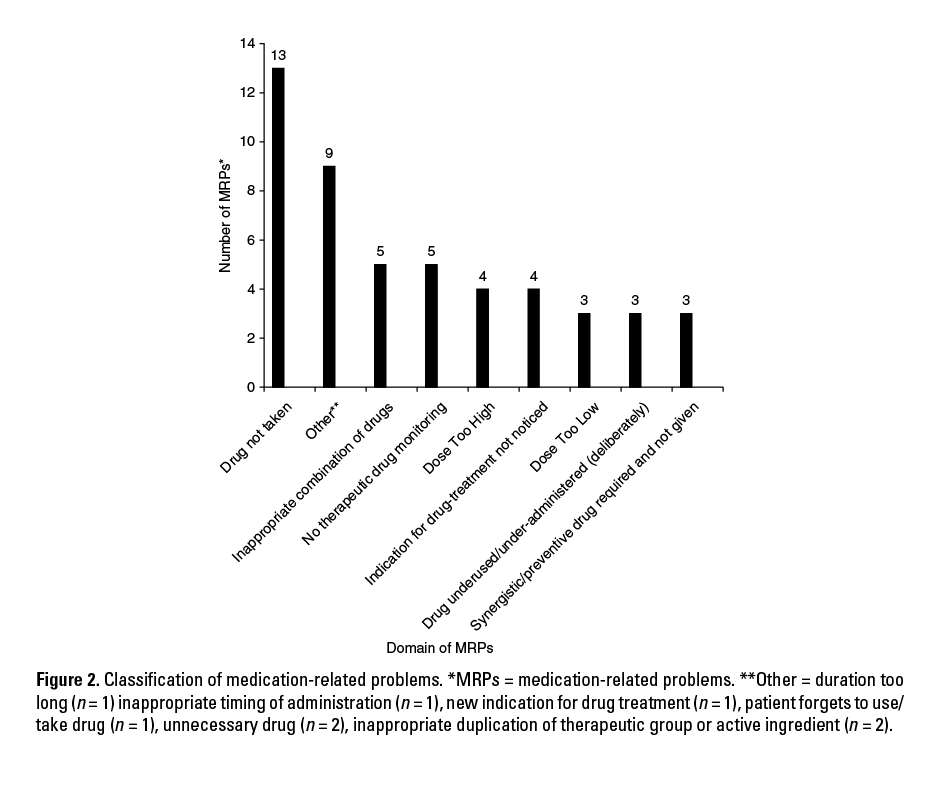

A total of 49 MRPs were discovered in patients who received TCS, with approximately 2 MRPs identified per patient. Of the MRPs identified by the pharmacist, 85.7% (n = 42) required follow-up and intervention from the providers. The most prevalent MRP was attributed to patients not taking medications as prescribed upon discharge. This included patients not being able to afford prescribed medications as well as patients who would take medications more or less frequently than prescribed. Twelve percent (n = 5) of MRPs identified involved inappropriate drug combinations. Other MRPs identified are shown in Figure 2. The acceptance rate of pharmacist’s recommendations by the providers was 92.8% (n = 39) for the identified MRPs that required follow-up with the providers.

The prospective group had an overall greater average reduction of FBG compared to the retrospective group. In addition, there was a greater reduction in average SBP and significant lowering of average DBP in the prospective group (Table 2).

Prior to the PATCH service, the TCS CPT codes 99495 and 99496 were not being utilized. During the pilot, a total of 30 TCS codes were charged and 76.7% were reimbursed. Payers included both Medicare and commercial insurance companies.

DISCUSSION

Several different approaches have been proposed to improve TOC in an effort to reduce readmissions. National agencies have established guidance toolkits to assist organizations in the TOC process.15,16 For example, the International Healthcare Institute developed the STAAR (State Action on Avoidable Readmissions) initiative that outlines key points to enhance TOC. Although these methods have improved readmission rates and patient outcomes, it is unclear which intervention is most effective in reducing avoidable readmissions.8-12,15

A common theme in each of these approaches is the importance of medication reconciliation and evidence-based medication management. As medication experts, pharmacists should serve as key members of the TOC team.

The core of the PATCH service was the ability of pharmacists to provide comprehensive patient-centered care by identifying MRPs and making evidence-based recommendations to providers to optimize medication use. MRPs have been estimated to cost approximately $177.4 billion per year and are estimated to be one of the top 5 causes of death in the elderly population.17 Identifying, resolving, and preventing MRPs can lead to cost savings as well as improved patient outcomes.

Our study revealed that patients in the prospective group had an 18% absolute reduction in all-cause 30-day acute health care utilization and reductions in BP and FBG compared to the retrospective group. Over a quarter of the MRPs identified were related to access and adherence issues. During the initial phone call, many patients attributed this discrepancy to the lack of knowledge of the new medications or changes to their previous medication regimen upon discharge. For example, patients might have been discharged with the hospital’s formulary alternative of their home medication only to discover that their insurance did not cover the new medication. Thus, they did not take their medication as prescribed. Other issues arose as patients started taking both the formulary alternative and their home medication, resulting in duplicate therapy. A prompt follow-up with the pharmacist via a phone call can quickly resolve these MRPs. The pharmacist was able to resolve these MRPs through patient education regarding medication changes and/or by providing therapeutic interchange recommendations to the physician. These results show the importance of prompt postdischarge medication reconciliation.

The success of the PATCH service can be attributed to several factors, such as attaining early support from administration and clinic staff. The PCMH integrated model allowed for close interactions between the PCP and pharmacist. Brief daily meetings with the staff minimized duplicate work. During these meetings, the pharmacist would let the RN care coordinator know who to contact; the meetings served as another venue to review patients and scheduling for the day with the providers. The collaborative workflow of the clinic fostered a strong relationship between the PCP and the pharmacist. Over 90% of the pharmacists’ recommendations were accepted by the providers.

The TCS pilot program was feasible and could be easily replicated. There are many steps with strict deadlines that must be met in order to use the CPT code requirements, including an interactive telephone call within 2 business days after discharge, medication reconciliation, and a face-to-face appointment within 1 to 2 weeks depending on the complexity of patient care. With the help of a pharmacist communicating with the patient, the office, and the PCPs, we were able to ensure we met all the requirements and attained maximum billing potential using the CPT billing code. The service was primarily delivered by a residency-trained clinical pharmacist but was also staffed by pharmacist extenders (pharmacy residents and students). The face-to-face appointments were scheduled in 2 consecutive 30-minute blocks with the pharmacist and the patient’s PCP; this method provided ample time to perform medication reconciliation, conduct patient interviews to assess disease state management, speak with providers regarding assessment, and plan for patients’ medication regimen prior to their 30-minute appointment.

Our study identified the positive impact pharmacists can have on TOC, but it was not without limitations. The pilot was not a randomized controlled study and was not adequately powered to show a reduction in acute health care utilization. Despite promising results, these data are based on a single center and only 30 patients received complete PATCH service. We also included several disease states, such as patients with COPD or requiring oral anticoagulation. However, we were unable to compare outcomes in these specific subgroups due to the small sample size and limited time frame for follow-up. In addition, patients may have utilized acute health care services outside of the affiliated academic teaching hospital, which we are unable to account for in our findings. In the future, we plan to collaborate with our state’s quality improvement organization to assist with tracking 30-day readmissions to outside hospitals for patients with Medicare. Pharmacists had an impact on the clinic quality indicators such as SBP, DBP, and FBG, but the lack of statistical significance for SBP and FBG may be attributed to the short follow-up period and the fact that overall the patients were relatively well-controlled at baseline. Due to the time constraints of this pilot, patients’ BP and FBG were only recorded up to 30 days after discharge. More clinically significant outcomes of FBG and BP control, such as number of cardiac events or HbA1c, may be investigated with extended follow-up.

During the initial operations of the pharmacist-managed TCS, we were presented with several barriers for successful implementation. The service had an overall capture rate of 40.5% (n = 30). This lower-than-expected capture rate may be attributed to the fact that the project occurred during the holiday season and patients and providers were unavailable. As the service developed, modifications were made to overcome these barriers to improve our capture rate. Initially, the hospital discharge report was run every other weekday. The discharge report was run Monday through Friday, and patients were contacted every weekday to increase enrollment and to allow increased use of appropriate CPT billing codes. In addition, during the initial phone call, some patients were unsure of the role of the pharmacist within the primary care setting and were initially not interested in the service. Marketing the service as a collaborative effort between their PCP and pharmacist improved the patients’ understanding of the service. Despite lower-than-expected capture rate, the service still reduced acute health care utilization in the prospective group compared to the retrospective group. This pilot program demonstrated potential benefit in decreasing acute health care utilization. These initial findings should be evaluated in adequately powered randomized controlled trials.

Despite challenges, the implementation of the PATCH service was successful. As a result of this pilot, the TCS has been expanded to 4 out of 14 ambulatory care pharmacists within the hospital system, and there are plans to expand this service to all 14 affiliated clinics. PCPs managing recently discharged patients who do not meet the criteria for the PATCH service can consult pharmacists to review and make recommendations to optimize medication regimens for compliance, fall risk, drug interactions, and cost. They also have the option to formally consult pharmacy to provide targeted disease management such as anticoagulation and diabetes management. Moreover, we plan to begin targeting and enrolling high-risk patients prior to discharge to further decrease readmissions rates. An inpatient pharmacist will initiate the service by performing a medication reconciliation and review, ensuring pertinent MRPs are addressed prior to the patients’ discharge. Once discharged, the inpatient pharmacist will handoff the medication reconciliation and review to the clinic pharmacist, who will then begin the PATCH service.

Outside of clinical outcomes, the economic impact of implementing a pharmacist-led TCS may be beneficial, especially in light of the transition to reimbursement models being tied to patient outcomes.18 Bloink and Adler19 reported the average reimbursement for the TCS CPT billing codes from CMS to be $162 for 99495 and $229 for 99496. The TCS CPT codes are more favorable than charging for an established office visit that is reimbursed at approximately $105 for CPT code 99214 and $141 for 99215.19 Moreover, by 2019, the use of primary care services is expected to increase from 15.07 million to 24.30 million visits.20 With the projected increased demand for these services and a limited supply of PCPs, there may be less time available to spend on medication therapy management. Pharmacists, serving their role as medication experts, may help fill this void as part of a TCS.

CONCLUSION

Our study shows that implementation of a pharmacist-managed TCS can decrease acute health care utilization and improve clinic quality indicators such as BP and glucose control. Pharmacists can also identify and resolve MRPs during key points in care transitions. However, further investigation through large randomized controlled trials is needed in order to assess the effectiveness of a scalable pharmacist-managed TCS handoff model in various clinical settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. They acknowledge Dr. Karen Jacobs and Dr. Joanna Ramirez for their assistance in the review of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Coleman EA, Boult C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):556-557.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167.

- Hines AL, Barrett ML, Jiang HJ, Steiner CA. Conditions with the largest number of adult hospital readmissions by payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #172. April 2014. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb172-Conditions-Readmissions-Payer.pdf.

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428.

- Rising KL, White LF, Fernandez WG, Boutwell AE. Emergency department visits after hospital discharge: A missing part of the equation. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):145-150.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html Accessed April 30, 2014

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services. Transitional care management services. http://www.nacns.org/docs/TransCareMgmtFAQ.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2014.

- Crotty M, Rowett D, Spurling L, Giles LC, Phillips PA. Does the addition of a pharmacist transition coordinator improve evidence-based medication management and health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long-term care facility? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2(4):257-264.

- Kucukarslan SN, Hagan AM, Shimp LA, Gaither CA, Lewis NJ. Integrating medication therapy management in the primary care medical home: A review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Health System Pharm. 2011;68(4):335-345.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):565-571.

- Steurbaut S, Leemans L, Leysen T, et al. Medication history reconciliation by clinical pharmacists in elderly inpatients admitted from home or a nursing home. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(10):1596-1603.

- Walker PC, Bernstein SJ, Jones JN, et al. Impact of a pharmacist-facilitated hospital discharge program: a quasi-experimental study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):2003-2010.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National action plan for adverse drug event prevention. 2014. http://health.gov/hcq/pdfs/ade-action-plan-508c.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2015.

- Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe. PCNE Classification for Drug-Related Problems V 5.01. Revised January 5, 2006. http://www.pcne.org/

upload/files/16_PCNE_classification_V5.01.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2015. - Boutwell AE, Johnson MB, Rutherford P, et al. An early look at a four-state initiative to reduce avoidable hospital readmissions. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2011;30(7):

1272-1280. - National Transitions of Care Coalition. Improving transitions of care: The vision of the National Transitions of Care Coalition. May 2008. http://www.ntocc.org/Portals/0/PDF/Resources/PolicyPaper.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2015.

- Ernst FR, Grizzle AJ. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: Updating the cost-of-illness model. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2001;41(2):192-199.

- Rosenthal MB. Beyond pay for performance—emerging models of provider-payment reform. New Engl J Med. 2008;359(12):1197-1200.

- Bloink J, Adler KG. Transitional care management services: New codes, new requirements. Fam Pract Manage. 2013;20(3):12-17.

- Hofer AN, Abraham JM, Moscovice I. Expansion of coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and primary care utilization. MilbankQ. 2011;89(1):69-89.

*PGY-2 Critical Care Pharmacy Resident, Department of Pharmacy Services, Orlando Regional Medical Center, Orlando, Florida; †Clinical Pharmacist - Ambulatory Care, Department of Pharmacy Services, Tampa General Hospital, Tampa, Florida; ‡Assistant Professor and Director of Research Education, Department of Internal Medicine, University of South Florida, Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida; §Director of Residency Programs/Education Coordinator, Department of Pharmacy Services, Tampa General Hospital, Tampa, Florida. Corresponding author: Amanda Martinez, PharmD, Department of Pharmacy Services, Tampa General Hospital, PO Box 1289, Tampa, FL 33601; phone: 813-844-5022; e-mail: amandamartinez@tgh.org