ISMP Medication Error Report Analysis

FDA Advise-ERR: Mefloquine—Not the Same as Malarone

Zoster Vaccine Is Not for the Immunosuppressed

TXA Mistaken as Tenecteplase

Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications

Michael R. Cohen, RPh, MS, ScD,* and Judy L. Smetzer, RN, BSN†

These medication errors have occurred in health care facilities at least once. They will happen again—perhaps where you work. Through education and alertness of personnel and procedural safeguards, they can be avoided. You should consider publishing accounts of errors in your newsletters and/or presenting them at your inservice training programs. Your assistance is required to continue this feature. The reports described here were received through the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Medication Errors Reporting Program. Any reports published by ISMP will be anonymous. Comments are also invited; the writers’ names will be published if desired. ISMP may be contacted at the address shown below. Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported directly to ISMP through the ISMP Web site (www.ismp.org), by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE, or via e-mail at ismpinfo@ismp.org. ISMP guarantees the confidentiality and security of the information received and respects reporters’ wishes as to the level of detail included in publications.

ISMP Medication Error Report Analysis

FDA Advise-ERR: Mefloquine—Not the Same as Malarone

Zoster Vaccine Is Not for the Immunosuppressed

TXA Mistaken as Tenecteplase

Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications

Michael R. Cohen, RPh, MS, ScD,* and Judy L. Smetzer, RN, BSN†

These medication errors have occurred in health care facilities at least once. They will happen again—perhaps where you work. Through education and alertness of personnel and procedural safeguards, they can be avoided. You should consider publishing accounts of errors in your newsletters and/or presenting them at your inservice training programs. Your assistance is required to continue this feature. The reports described here were received through the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Medication Errors Reporting Program. Any reports published by ISMP will be anonymous. Comments are also invited; the writers’ names will be published if desired. ISMP may be contacted at the address shown below. Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported directly to ISMP through the ISMP Web site (www.ismp.org), by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE, or via e-mail at ismpinfo@ismp.org. ISMP guarantees the confidentiality and security of the information received and respects reporters’ wishes as to the level of detail included in publications.

ISMP Medication Error Report Analysis

FDA Advise-ERR: Mefloquine—Not the Same as Malarone

Zoster Vaccine Is Not for the Immunosuppressed

TXA Mistaken as Tenecteplase

Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications

Michael R. Cohen, RPh, MS, ScD,* and Judy L. Smetzer, RN, BSN†

These medication errors have occurred in health care facilities at least once. They will happen again—perhaps where you work. Through education and alertness of personnel and procedural safeguards, they can be avoided. You should consider publishing accounts of errors in your newsletters and/or presenting them at your inservice training programs. Your assistance is required to continue this feature. The reports described here were received through the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Medication Errors Reporting Program. Any reports published by ISMP will be anonymous. Comments are also invited; the writers’ names will be published if desired. ISMP may be contacted at the address shown below. Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported directly to ISMP through the ISMP Web site (www.ismp.org), by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE, or via e-mail at ismpinfo@ismp.org. ISMP guarantees the confidentiality and security of the information received and respects reporters’ wishes as to the level of detail included in publications.

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(11):961–964

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5011-961

FDA ADVISE-ERR: MEFLOQUINE—NOT THE SAME AS MALARONE

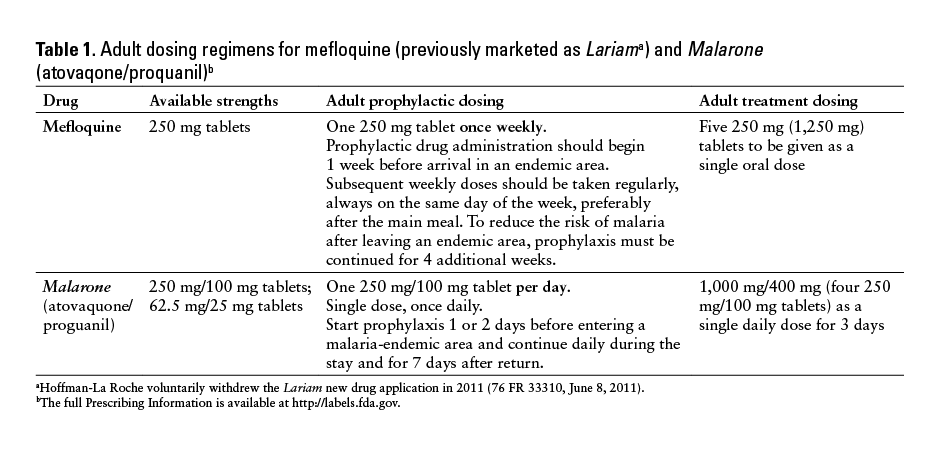

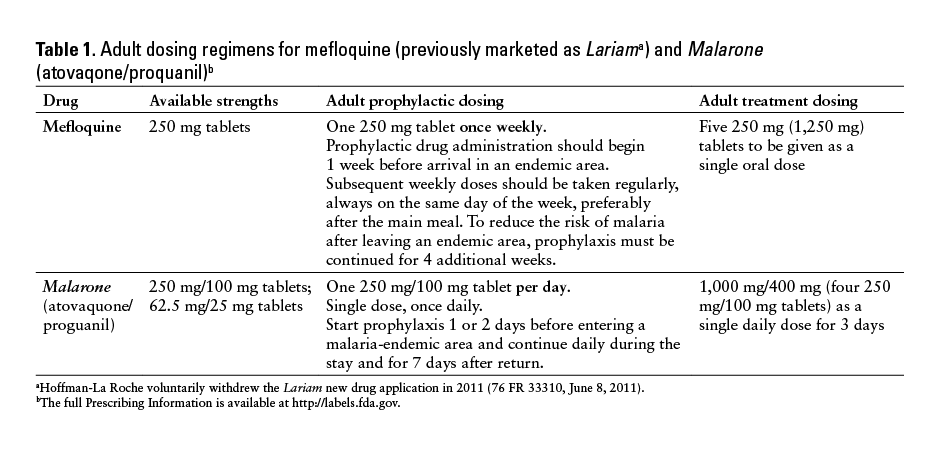

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and ISMP have received reports that describe errors associated with the wrong frequency of administration with mefloquine as well as wrong drug errors in which mefloquine was dispensed instead of the intended Malarone (atovaquone/proguanil). Both mefloquine (previously marketed as Lariam [Hoffman-La Roche voluntarily withdrew the Lariam new drug application in 2011 (76 FR 33310, June 8, 2011)]) and Malarone are FDA approved for use in the treatment and prophylaxis of malaria, but they have different dosing regimens (Table 1).

Treatment Dosing

One report described 2 patients for whom mefloquine 250 mg was prescribed to be taken daily instead of weekly for malaria prophylaxis. After taking mefloquine daily for 11 days, both patients experienced a “cloudy head,” dizziness, nausea, and vomiting that persisted for more than 10 days after mefloquine was stopped.

Three reports described prescriptions written for Malarone, but the pharmacy mistakenly dispensed

mefloquine. The first patient, an 18-year-old man, took 4 tablets (1 g) of mefloquine daily for 2 to 3 days instead of the prescribed Malarone and -developed a headache, nausea, vomiting, and confusion. In the other 2 events, the dispensing error was caught by the patients prior to taking the incorrect medication.

Although most of the reports did not state a reason why these errors occurred, knowledge deficits may have contributed to the mix-ups. One report stated that the incorrect substitution was performed because the pharmacist thought mefloquine was the generic of Malarone. Health care providers may be unfamiliar with antimalarial products due to infrequent use. Further, mefloquine and Malarone have overlapping tablet strengths and similar approved uses as antimalarial products, making confusion more likely.

Mistakenly believing that mefloquine and Malarone are the same or that they have the same dosing regimen for antimalarial prophylaxis and treatment may lead to serious adverse events including vomiting, syncope, QT prolongation, paranoia, anxiety, depression, or inadequate prophylaxis.

Safe Practice Recommendations

Health care providers should consider the following recommendations to reduce the risk of errors.

- Include brand and generic name. Prescribe -Malarone using both the brand and generic names, Malarone (atovaquone/proguanil), to provide redun-dancy and a greater differentiation from mefloquine.

- Include the indication on the prescription. Prescribers should indicate whether the prescription or order is for prophylaxis or treatment of malaria.

- Verify every order. Verify prescriptions for antimalarial prophylaxis and treatment, which may not be commonly dispensed. This includes confirmation of the drug, frequency of administration, and dosing regimen of Malarone or mefloquine with each order or prescription.

- Set frequency limits. In order entry systems, establish an alert that will appear if mefloquine is prescribed daily and if Malarone is prescribed weekly.

- Provide counseling. Counsel all patients who are pre-scribed antimalarial products regarding their purpose (prophylaxis or treatment) and directions for use. When dispensing mefloquine, advise patients to read the Medication Guide and to call their health care provider if they have any questions.

FDA Advise-ERR was provided by Jacqueline Sheppard, PharmD, and Vicky Borders-Hemphill, PharmD, from the FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology, Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis.

ZOSTER VACCINE IS NOT FOR THE IMMUNOSUPPRESSED

A 90-year-old man went to a community pharmacy to refill a prescription for 60 mg of prednisone daily for an unspecified condition. While there, the man was told about Zostavax (zoster vaccine, live), and he expressed an interest in receiving the vaccine. He was asked to complete a vaccine screening questionnaire, and billing for the vaccine was processed. Unfortunately, the pharmacist did not review the completed questionnaire, and when Zostavax was entered into the computer system, she did not notice a patient-specific alert to avoid administration of Zostavax because the patient was taking an immunosuppressant. Another pharmacist was notified that the man was waiting for the vaccine. This pharmacist reviewed the vaccine screening questionnaire but stopped part way through when she noticed the man had indicated that he did not know if he had received a shingles vaccine in the past. The pharmacist verified that the man had not received the vaccine by checking the state immunization information system. She then forgot to review the remainder of the questionnaire, missing that the patient had indicated that he was taking prednisone or an immunosuppressant.

The pharmacist prepared the vaccine while teaching a pharmacy intern about proper mixing. Once she was ready to administer it, the man mentioned that he had been taking prednisone 40 to 60 mg daily for more than 3 months, but the pharmacist did not recall that Zostavax was contraindicated in patients with long-term steroid use. The vaccine was administered; when completing the documentation, the pharmacist remembered to review the remainder of the vaccine screening questionnaire and realized the contraindication with long-term steroid use. The man was notified of the error, and his physician elected to prescribe valacyclovir to lessen the risk of an adverse reaction.

The risk of herpes zoster and its accompanying morbidity and mortality is much greater among people who are immunosuppressed. Review of vaccination status for herpes zoster and screening for diseases that might make patients immunocompromised should be a key component of the medical assessment for patients 60 years and older, especially if they might be anticipating initiation of immunosuppressive treatments. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) states that the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine, varicella vaccines (including in combination with MMR), and the zoster vaccine are contraindicated in people receiving high-dose steroids. High-dose steroids are defined as 2 mg/kg or more, or a total of 20 mg/day or more of prednisoneor the equivalent for people who weigh more than 10 kg, when administered for

2 weeks or more. MMR, varicella, and zoster -vaccines should not be given for at least 1 month after the discontinuation of steroids. The vaccine is also not -recommended for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia because it may cause a shingles infection due to the -compromised immune system (http://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/leukemia-chronic-

lymphocytic-cll/treatment-options).

One might also question giving the zoster vaccine to a 90-year-old person, but there is no upper age limit for administration of the zoster vaccine. The incidence of herpes zoster increases with age; about half of people living until the age of 85 years will develop shingles. ACIP recommends the vaccine for people 60 years and older, even though the vaccine’s efficacy decreases as the recipient’s age increases (http://www.immunize.org/askexperts/experts_zos.asp). In general, with increasing age at vaccination, the vaccine is more effective in reducing the severity of zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia than it is in reducing its occurrence. For more information, see the ACIP General Recommendations on Immunization (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6002a1.htm) and other vaccine-specific recommendations (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/).

TXA MISTAKEN AS TENECTEPLASE

A trauma patient in the emergency department (ED) required tranexamic acid (an antifibrinolytic) to control bleeding. The physician told the nurse to get TXA. The nurse thought he said TNK (tenecteplase), a thrombolytic agent. She had the syringe in her hand and gave it to the physician to administer. Referring to tranexamic acid, the physician replied, “You can’t push TXA; it has to be an infusion.” At that point, the nurse said she thought TNK was requested, and the potentially fatal error was recognized and avoided. Both medications may be stored in automated -dispensing cabinets (ADCs) in EDs and may be available via override since tranexamic acid is sometimes used to treat trauma patients who are bleeding and tenecteplace is used to treat emergent cardiac cases. If tenecteplase had been administered, the patient may have bled, leading to a fatal event.

After the close call, electronic references for TNK and TXA were removed from information technology systems and warnings were placed in the computerized prescriber order entry system and ADC databases. The alerts, which state the indications for each drug, must be acknowledged before medication removal. Staff education about the use of these error-prone abbreviations in written, electronic, or spoken communications was also provided. This is another example of why ISMP’s list of error-prone abbreviations (www.ismp.org/sc?id=558) includes the recommendation to avoid the abbreviation of any drug name.

GUIDELINES FOR ADULT IV PUSH MEDICATIONS

ISMP has released Safe Practice Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications, which can be found at www.ismp.org/sc?id=563. The guidelines are a compilation of safe practices that were developed as a result of a 2-day facilitated summit held in September 2014. The summit was funded through the generous support of BD. Fifty-six participants, representing a range of frontline providers, professional organizations, regulatory bodies, and product vendors from across the United States, attended the summit. Draft guidelines were developed and reviewed by participants and shared on ISMP’s Web site for comment. ISMP -considered each comment when finalizing the safe practices. The guidance statements in the document represent a consensus for safe practices -associated with IV push medication preparation and administration to adults. We thank those who submitted comments and our summit participants for their dedication to this project. Please take a moment to review the guidelines and share them with your colleagues. ![]()

*President, Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 200 Lakeside Drive, Suite 200, Horsham, PA 19044; phone: 215-947-7797; fax: 215-914-1492; e-mail: mcohen@ismp.org; Web site: www.ismp.org. ‡Vice President, Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Horsham, Pennsylvania.