Original Article

Pharmacist Involvement at Discharge with The Joint

Commission Heart Failure Core Measure: Challenges and

Lessons Learned

Holly Herring, PharmD, BCPS*; Winter Smith, PharmD, BCPS†; Toni Ripley, PharmD, BCPS, AQ-Cardiology†; and Kevin Farmer, PhD‡

Original Article

Pharmacist Involvement at Discharge with The Joint

Commission Heart Failure Core Measure: Challenges and

Lessons Learned

Holly Herring, PharmD, BCPS*; Winter Smith, PharmD, BCPS†; Toni Ripley, PharmD, BCPS, AQ-Cardiology†; and Kevin Farmer, PhD‡

Original Article

Pharmacist Involvement at Discharge with The Joint

Commission Heart Failure Core Measure: Challenges and

Lessons Learned

Holly Herring, PharmD, BCPS*; Winter Smith, PharmD, BCPS†; Toni Ripley, PharmD, BCPS, AQ-Cardiology†; and Kevin Farmer, PhD‡

Abstract

Background: Pharmacists are vital health care providers to patients with heart failure (HF), but their compliance to the HF core measure has not been clearly defined.

Objective: The objective of this study was to measure the impact of pharmacist involvement at discharge on compliance with The Joint Commission HF core measure.

Methods: This prospective study was conducted at a 361-bed academic teaching institution. A pharmacist performed chart reviews just prior to discharge on adult patients with a preliminary diagnosis of HF (ie, clinical suspicion) to evaluate compliance with the HF core measure. The pharmacist then intervened as needed to ensure compliance. The primary outcome was HF core measure compliance rates with pharmacist involvement at discharge compared to rates during the same 3-month period during the previous year (without pharmacist involvement).

Results: Of 92 patients admitted with clinical suspicion of HF, the pharmacist was able to review 45 patient charts at discharge (49%). The majority of interventions made by the pharmacist were due to medication discrepancies within the discharge instructions found during medication reconciliation. Rates of compliance with the HF core measure did not differ between the period with pharmacist involvement at discharge and the previous period (without pharmacist involvement, P = .39). However, barriers to compliance related to discharge medication documentation, interdisciplinary communication, and manpower were identified through the process.

Conclusion: Although pharmacist involvement at discharge did not translate into improved compliance with the HF core measure, systematic barriers to compliance were identified and are currently being addressed.

Key Words—core measures, heart failure, performance measures, pharmacist, The Joint Commission

Hosp Pharm—2014;49:1017–1021

Abstract

Background: Pharmacists are vital health care providers to patients with heart failure (HF), but their compliance to the HF core measure has not been clearly defined.

Objective: The objective of this study was to measure the impact of pharmacist involvement at discharge on compliance with The Joint Commission HF core measure.

Methods: This prospective study was conducted at a 361-bed academic teaching institution. A pharmacist performed chart reviews just prior to discharge on adult patients with a preliminary diagnosis of HF (ie, clinical suspicion) to evaluate compliance with the HF core measure. The pharmacist then intervened as needed to ensure compliance. The primary outcome was HF core measure compliance rates with pharmacist involvement at discharge compared to rates during the same 3-month period during the previous year (without pharmacist involvement).

Results: Of 92 patients admitted with clinical suspicion of HF, the pharmacist was able to review 45 patient charts at discharge (49%). The majority of interventions made by the pharmacist were due to medication discrepancies within the discharge instructions found during medication reconciliation. Rates of compliance with the HF core measure did not differ between the period with pharmacist involvement at discharge and the previous period (without pharmacist involvement, P = .39). However, barriers to compliance related to discharge medication documentation, interdisciplinary communication, and manpower were identified through the process.

Conclusion: Although pharmacist involvement at discharge did not translate into improved compliance with the HF core measure, systematic barriers to compliance were identified and are currently being addressed.

Key Words—core measures, heart failure, performance measures, pharmacist, The Joint Commission

Hosp Pharm—2014;49:1017–1021

Abstract

Background: Pharmacists are vital health care providers to patients with heart failure (HF), but their compliance to the HF core measure has not been clearly defined.

Objective: The objective of this study was to measure the impact of pharmacist involvement at discharge on compliance with The Joint Commission HF core measure.

Methods: This prospective study was conducted at a 361-bed academic teaching institution. A pharmacist performed chart reviews just prior to discharge on adult patients with a preliminary diagnosis of HF (ie, clinical suspicion) to evaluate compliance with the HF core measure. The pharmacist then intervened as needed to ensure compliance. The primary outcome was HF core measure compliance rates with pharmacist involvement at discharge compared to rates during the same 3-month period during the previous year (without pharmacist involvement).

Results: Of 92 patients admitted with clinical suspicion of HF, the pharmacist was able to review 45 patient charts at discharge (49%). The majority of interventions made by the pharmacist were due to medication discrepancies within the discharge instructions found during medication reconciliation. Rates of compliance with the HF core measure did not differ between the period with pharmacist involvement at discharge and the previous period (without pharmacist involvement, P = .39). However, barriers to compliance related to discharge medication documentation, interdisciplinary communication, and manpower were identified through the process.

Conclusion: Although pharmacist involvement at discharge did not translate into improved compliance with the HF core measure, systematic barriers to compliance were identified and are currently being addressed.

Key Words—core measures, heart failure, performance measures, pharmacist, The Joint Commission

Hosp Pharm—2014;49:1017–1021

Hosp Pharm 2014;49(11):1017–1021

2014 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj4911-1017

In 2001, The Joint Commission (TJC) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed evidence-based performance measures, termed core measures or quality measures, for hospitals to comply with in order to improve safety and quality of care for patients with heart failure (HF).1 Hospitals should strive for 100% compliance to each of the 4 criterions of the HF core measure: (1) discharge instructions, (2) evaluation of left ventricular (LV) systolic function, (3) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy for patients with left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction or documentation of contraindication to such therapy, and (4) smoking cessation advice/counseling.2

To be included in the HF core measure, a patient must be admitted to the hospital with a principal diagnosis of HF. Several practices must take place to meet these standards and be in compliance with the HF core measure criteria. For the discharge instruction criteria, patients must receive instructions regarding specific symptoms that warrant treatment, diet and weight management, and activity level. Patients must also be given complete discharge medication instructions that include documentation of home medications and new medications to be continued following discharge. LV systolic function must be recorded in the patient’s medical record as an ejection fraction (EF). Patients with LV systolic dysfunction and an EF less than 40% should receive ACEI or ARB therapy, unless a contraindication is documented. Finally, patients who smoke must be given advice or counseling on smoking cessation. All elements of these 4 criteria must be clearly documented in the patient’s medical record.

TJC recognizes pharmacists as health care professionals who aid in the implementation of core measures. Beginning in 2008, TJC allowed documentation of LV systolic function and contraindications to ACEI or ARB therapy by a pharmacist to meet the HF core measure criteria.2 Further, pharmacists can aid in the medication reconciliation process to help ensure that patients receive a complete list of discharge

medications.3 With this authorization from TJC, pharmacists could potentially have a discrete role in achieving compliance with the HF core measure.

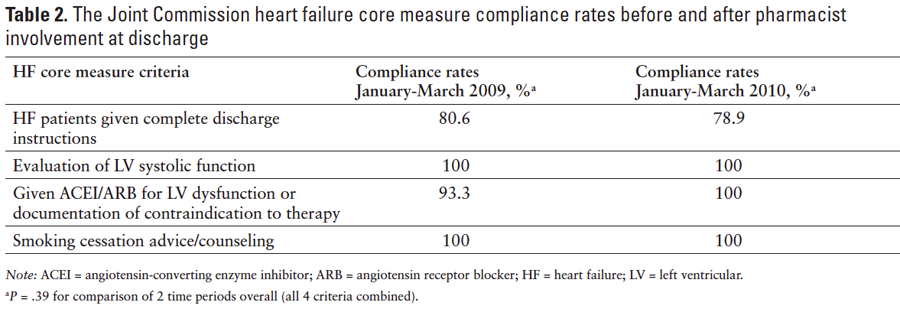

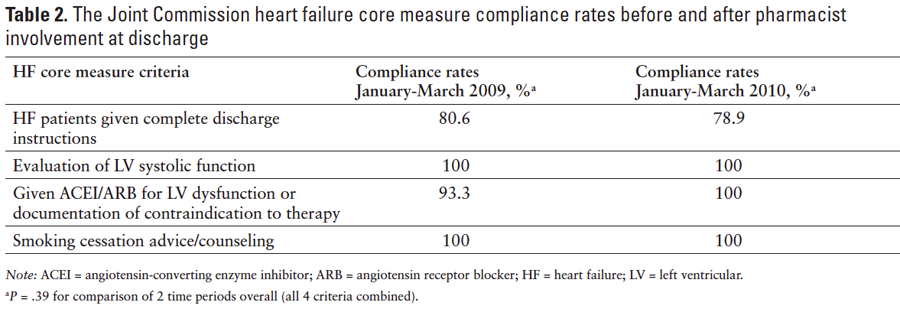

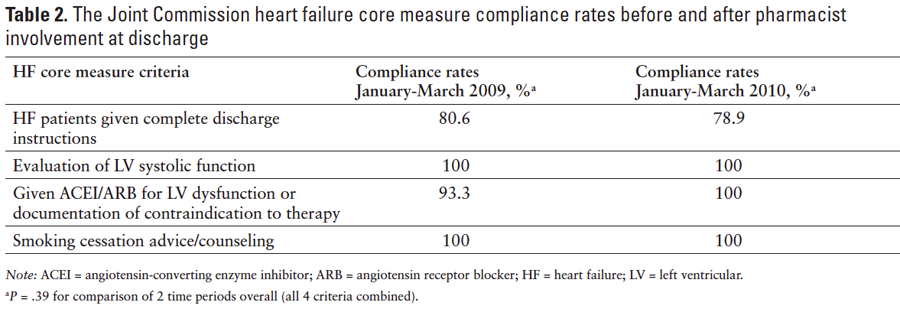

The OU Medical Center is a 361-bed adult academic teaching institution serving central Oklahoma. Historically, HF core measures have largely been managed by OU Medical Center nursing leadership and staff. Rates of compliance with the HF core measure at OU Medical Center from January 2009 to March 2009 were as follows: 80.6% of HF patients were given complete discharge instructions, 100% had documentation of LV systolic function, 93.3% were prescribed an ACEI or ARB for LV systolic dysfunction or a contraindication to therapy was documented, and 100% were provided smoking cessation counseling. At that time, a nurse leader, the medical staff, and nursing staff were ultimately responsible for compliance to the core measure for each patient with a principal diagnosis of HF. The nurse leader worked to ensure documentation of LV systolic function, appropriate drug therapy (if indicated for an EF <40%), or documentation of a contraindication to therapy. Prior to discharge, home medication orders were completed by the physician. Then, the nursing staff transcribed the medication orders to a discharge instruction sheet that was given to the patient, which also included counseling on diet and weight management, activity level, and specific symptoms that warrant further treatment. Written smoking cessation counseling for patients with a smoking history was also included on the discharge instruction sheet. Final diagnostic codes were assigned after discharge. A quality nurse analyst reviewed each patient chart coded with a principal diagnosis of HF for compliance with the HF core measure and entered compliance status (compliant vs noncompliant) into a database. This information is submitted to and publicly reported by the CMS and the US Department of Health and Human Services (http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov).

In Fall 2009, opportunities for improvement in compliance with 2 of the HF core measure criteria were identified: proportion of patients receiving complete discharge instructions and an ACEI/ARB for LV systolic dysfunction. Therefore, a pharmacist joined the nurse leader and patient care team (nurses and physicians) to help improve compliance to the HF core measure. The purpose of this study was to measure the impact of pharmacist involvement at discharge on compliance with the overall HF core measure.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a prospective study conducted at discharge on patients with a principal diagnosis of HF from January 2010 through March 2010. Patients between the ages of 18 and 100 years admitted with an initial principal diagnosis of HF were included. Of note, because the final coding of diagnosis occurs after patient discharge, all patients with a preliminary diagnosis code (ie, clinical suspicion of HF) were included for the initial chart review. Patients were excluded if they were transferred to other facilities prior to discharge. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board. Informed consent was waived on the basis that the research involved no more than minimal risk to the participants.

Intervention

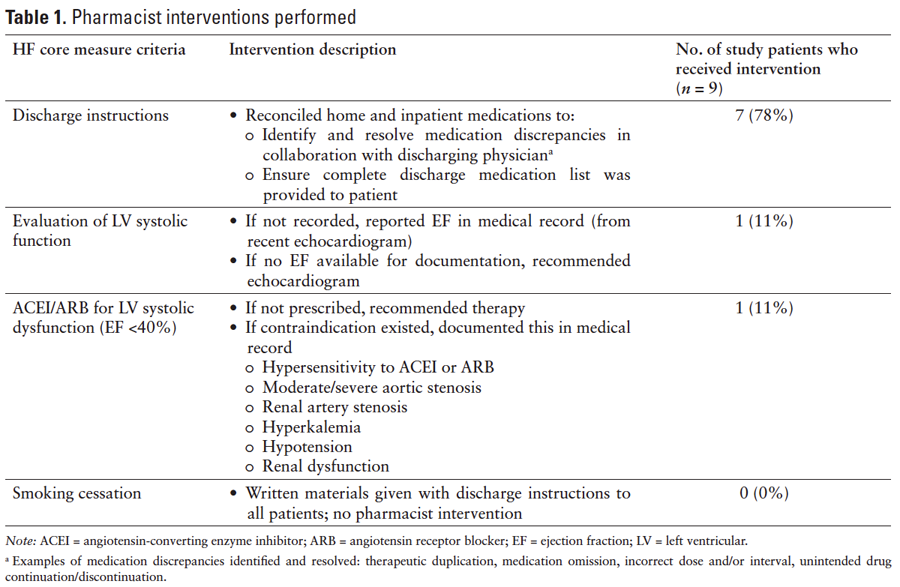

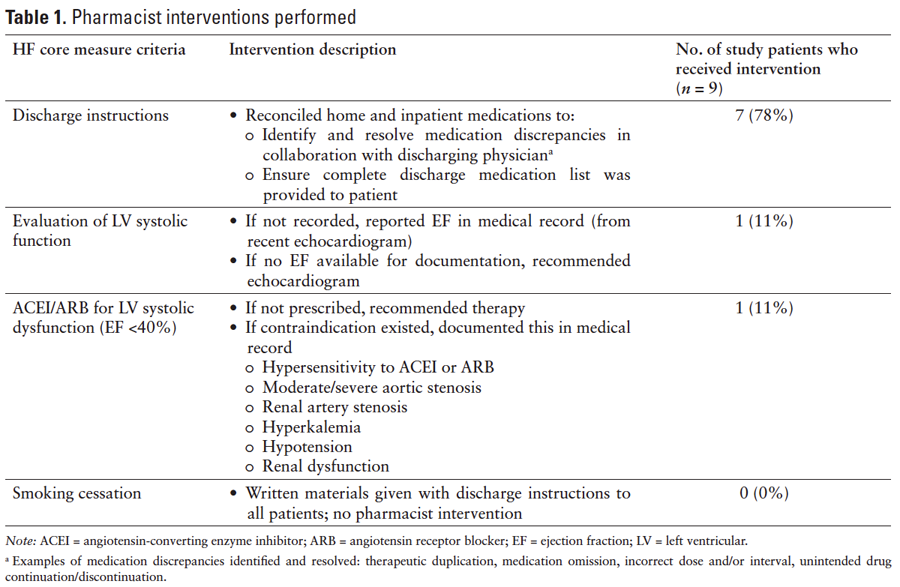

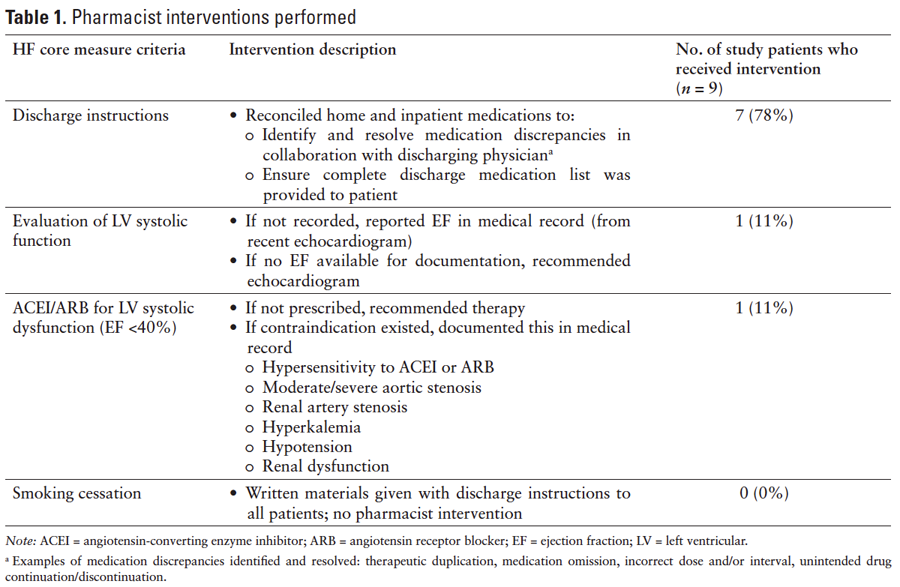

The pharmacist was notified by the nurse of patients with HF who were being discharged. The pharmacist performed chart reviews 1 to 3 hours prior to discharge to evaluate compliance with the HF core measure. The pharmacist then intervened as needed based on this chart review to ensure compliance with the HF core measure. The specific interventions are defined in Table 1.

Outcomes Measured

The primary outcome was HF core measure compliance rates with pharmacist involvement at discharge compared to rates during the same 3-month period during the previous year (January 2009 to March 2009, without pharmacist involvement). Electronic medical records and hardcopy medical charts served as principal data sources. The quality nurse analyst reported compliance rates to study personnel for statistical analysis. Compliance rates were then collected as nominal variables and compared using the chi-square test.

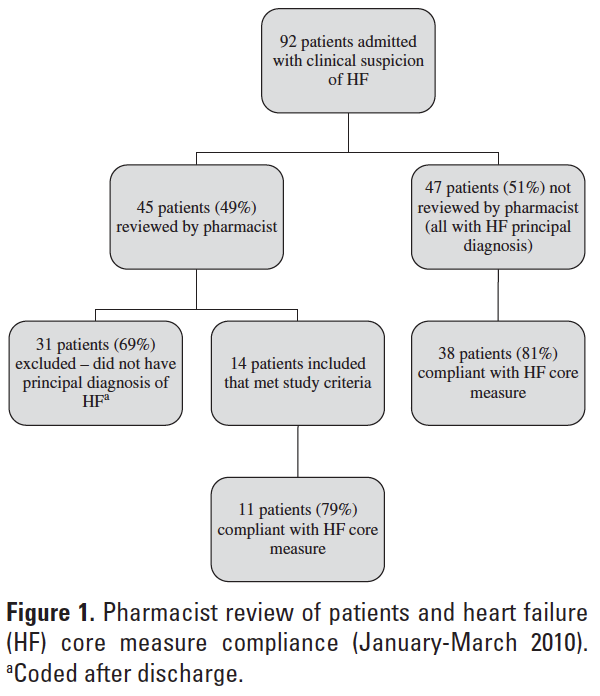

RESULTS

During the study period (January 2010 to March 2010), 92 patients were admitted with clinical suspicion of HF. Of these 92 patients, the pharmacist reviewed 45 patient charts at discharge (49%). Thirty-one of the 45 patients reviewed by the pharmacist were excluded from final analysis due to the correction of the coded medical diagnosis after discharge, leaving 14 patients for final analysis (14/45; 31%) (Figure 1).

The compliance rates to the TJC HF core measure with pharmacist involvement from January 2010 to March 2010 were reported as follows: 78.9% were given complete discharge instructions, 100% had documentation of LV systolic function, 100% were prescribed an ACEI or ARB for LV systolic dysfunction, and 100% were provided smoking cessation counseling. No difference in these rates was found compared to the control period of January 2009 to March 2009 without pharmacist involvement (P = .39) (Table 2).

Five of the 14 (36%) patients reviewed by the pharmacist were compliant with all 4 criteria of the HF core measure; therefore, no intervention was necessary. The pharmacist performed interventions on the remaining 9 patients, and the types of interventions are summarized in Table 1. The majority of interventions (77.8%) were due to medication discrepancies within the discharge instructions that were found during medication reconciliation. The most common medication discrepancy was the omission of medications from the physician discharge orders to the discharge instructions at the time of transcription.

Discussion

Pharmacist involvement did not translate into improved compliance with the HF core measure. There were no additional process changes that would have affected the results during or between study periods. The small sample size of patients included in the final analysis may have impacted these data. In spite of this limitation, the study provided insight into barriers that exist to meeting the core measure and into the feasibility of utilizing pharmacists to improve adherence.

Barriers to meeting the core measure manifested primarily in discharge instructions. Completeness of discharge instructions was the lowest area of compliance during both timeframes, with complete discharge medication instructions being the principal component of noncompliance. Physicians often dictated discharge summaries after patients were released from the hospital, and the dictated summaries were often inconsistent with the discharge orders provided for transcription at the time of discharge. Medications were not reconciled between the original discharge orders and dictated summaries, because the dictation was done after discharge; therefore, medications were often omitted from the patient’s discharge instructions. Such discrepancies are unlikely to be avoided without a change in this process. These findings are similar to a study in which compliance with discharge instructions remained lower than anticipated because of documentation issues within the medication reconciliation process.4 Changes in the discharge medication transcription process at our institution are currently in process to address this systematic problem.

Another barrier to compliance was the lack of a streamlined process at discharge. During the study, 3 people were involved in the review and reporting process for HF patients (nurse leader, quality nurse analyst, and pharmacist) as described earlier. With so many health care professionals involved, notification of HF patients being discharged was inconsistent and the pharmacist was not always notified of discharge patients for review. Also, the manpower needed for review of all HF patients at the time of discharge was greater than what one pharmacist could accommodate; one pharmacist was allocated 30% time to assume this responsibility. This appeared to be insufficient, because the pharmacist was only able to review half of the patients (45/92) with a clinical suspicion of HF. Furthermore, since the pharmacist relied on preliminary diagnosis codes (ie, clinical suspicion of HF) to identify HF patients, the majority of the pharmacist’s effort was spent on review of patients without a final primary diagnosis of HF. The feasibility of routinely including pharmacists at the point of discharge for each HF patient would likely require multiple pharmacists dedicated to evaluating compliance with the core measure, including evenings and weekends. Given the high baseline compliance with the HF core measure, the added value of additional health care professionals is uncertain. The current process has been streamlined such that one person, a HF quality nurse coordinator (0.5 full-time equivalent) is solely responsible for the review HF patients and compliance to TJC HF core measure. Prior to this study, a HF quality nurse coordinator was not part of our institution’s health care team. This has led to a more efficient approach that focuses on HF patients from admission to discharge, ultimately reducing unnecessary review and improving communication.

Future research should focus on interventions to improve the medication reconciliation process for HF patients. A study is currently evaluating the role of pharmacists in the discharge medication reconciliation process and the reduction of unintentional medication errors at discharge.5 This trial may provide insight into the value of pharmacists in the medication reconciliation process, but future studies should focus on the role of pharmacists in the medication reconciliation process at discharge for HF patients and compliance with TJC HF core measure.

CONCLUSION

In this investigation, addition of a pharmacist to a multidisciplinary team did not improve compliance to TJC HF core measure. However, systematic issues contributing to noncompliance were identified. Quality improvement measures are planned or in place to address these issues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no financial or institutional conflicts of interest to report. Holly Herring was previously Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Oklahoma College of Pharmacy, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

REFERENCES

- The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Comprehensive review of development and testing for national implementation of hospital core measures. http://www.jointcommission.org. Accessed September 27, 2009.

- Quality Net. Specifications manual for national hospital inpatient quality measures. Version 2.5b. http://www.qualitynet.org. Accessed September 20, 2009.

- Hinojosa C, Giardina J, K Radtke, Vournazos C. HF core measures – a multidisciplinary approach [abstract]. Heart Lung: J Acute Crit Care. 2009;38:277.

- Coons J, Fera T. Multidisciplinary team for enhancing care for patients with acute myocardial infarction or HF. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1274-1278.

- AHS Cancer Control Alberta. The impact of pharmacist discharge medication reconciliation on unintentional medication discrepancies from inpatient discharges at the Alberta Cancer Board Cross Cancer Institute. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2000. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01226589. Accessed May 26, 2014.

*Pharmacist, Integris Health Edmond, Edmond, Oklahoma; †Associate Professor, ‡Professor, Department of Pharmacy: Clinical and Administrative Sciences, University of Oklahoma College of Pharmacy, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Corresponding author: Holly Herring, PharmD, BCPS, Integris Health Edmond, 4801 Integris Parkway, Edmond, OK 73034; e-mail: holly.herring22@yahoo.com