ISMP Medication Error Report Analysis

Propylene Glycol Toxicity with Stoss Therapy

State Drug Tracking Database Helps Prevent an Error

Where Did That Medication Come From?

Expiration Date Difficult to Read

Michael R. Cohen, RPh, MS, ScD,* and Judy L. Smetzer, RN, BSN†

ISMP Medication Error Report Analysis

Propylene Glycol Toxicity with Stoss Therapy

State Drug Tracking Database Helps Prevent an Error

Where Did That Medication Come From?

Expiration Date Difficult to Read

Michael R. Cohen, RPh, MS, ScD,* and Judy L. Smetzer, RN, BSN†

ISMP Medication Error Report Analysis

Propylene Glycol Toxicity with Stoss Therapy

State Drug Tracking Database Helps Prevent an Error

Where Did That Medication Come From?

Expiration Date Difficult to Read

Michael R. Cohen, RPh, MS, ScD,* and Judy L. Smetzer, RN, BSN†

These medication errors have occurred in health care facilities at least once. They will happen again—perhaps where you work. Through education and alertness of personnel and procedural safeguards, they can be avoided. You should consider publishing accounts of errors in your newsletters and/or presenting them at your inservice training programs.

Your assistance is required to continue this feature. The reports described here were received through the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Medication Errors Reporting Program. Any reports published by ISMP will be anonymous. Comments are also invited; the writers’ names will be published if desired. ISMP may be contacted at the address shown below.

Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported directly to ISMP through the ISMP Web site (www.ismp.org), by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE, or via e-mail at ismpinfo@ismp.org. ISMP guarantees the confidentiality and security of the information received and respects reporters’ wishes as to the level of detail included in publications.

These medication errors have occurred in health care facilities at least once. They will happen again—perhaps where you work. Through education and alertness of personnel and procedural safeguards, they can be avoided. You should consider publishing accounts of errors in your newsletters and/or presenting them at your inservice training programs.

Your assistance is required to continue this feature. The reports described here were received through the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Medication Errors Reporting Program. Any reports published by ISMP will be anonymous. Comments are also invited; the writers’ names will be published if desired. ISMP may be contacted at the address shown below.

Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported directly to ISMP through the ISMP Web site (www.ismp.org), by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE, or via e-mail at ismpinfo@ismp.org. ISMP guarantees the confidentiality and security of the information received and respects reporters’ wishes as to the level of detail included in publications.

These medication errors have occurred in health care facilities at least once. They will happen again—perhaps where you work. Through education and alertness of personnel and procedural safeguards, they can be avoided. You should consider publishing accounts of errors in your newsletters and/or presenting them at your inservice training programs.

Your assistance is required to continue this feature. The reports described here were received through the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Medication Errors Reporting Program. Any reports published by ISMP will be anonymous. Comments are also invited; the writers’ names will be published if desired. ISMP may be contacted at the address shown below.

Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported directly to ISMP through the ISMP Web site (www.ismp.org), by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE, or via e-mail at ismpinfo@ismp.org. ISMP guarantees the confidentiality and security of the information received and respects reporters’ wishes as to the level of detail included in publications.

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(4):261–263

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5004-261

PROPYLENE GLYCOL TOXICITY WITH STOSS THERAPY

A 7-month-old infant (9.1 kg) was hospitalized with nutritional rickets and started on stoss therapy (from the German word for “to bump”), a high-dose vitamin D regimen that involves giving up to 600,000 units by mouth over a 24-hour period (www.ismp.org/sc?id=439). The infant was given 6 doses of 100,000 units every 2 hours (600,000 units total). The hospital carried ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) oral solution from Virtus Pharmaceuticals. The product, regulated as a dietary supplement, contains 8,000 units/mL. As a supplement, the labeled dose of the solution is just 2 drops, or 400 units.

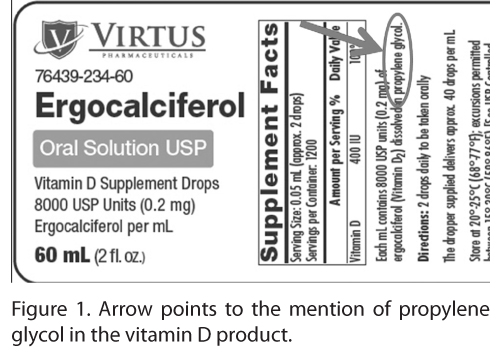

Fineprint on the label side-panel mentions that it is dissolved in propylene glycol (Figure 1), but the amount is not stated on this or other US ergocalciferol liquid products that contain propylene glycol.

Propylene glycol is a clear, colorless, odorless, and tasteless product used as a stabilizer, thickener, and texturizer. The ergocalciferol oral solution contains 103.6 g/100 mL of propylene glycol. The infant received 600,000 units of vitamin D2, equivalent to 75 mL of solution or 77.7 g of propylene glycol. According to the World Health Organization, this far exceeds the maximum tolerable amount of 25 mg/kg/day (or 227.5 mg for the baby in this event). In fact, the baby was exposed to 340 times the maximum amount, which led to acute renal failure. The infant’s serum creatinine rose from 0.22 mg/dL to 3 mg/dL. Fortunately, the child survived. Renal toxicity has occurred in neonates who were given HIV medications such as Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir) oral solution, which also uses propylene glycol as a carrier given the lack of better alternatives for solubility of this drug (www.ismp.org/sc?id=442).

As a dietary supplement, vitamins are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). FDA, which received this error report, should require manufacturers to state the propylene glycol ingredient more prominently on the label, including the amount in the container. Since all liquid vitamin D2 products have propylene glycol, consider preparing an approximate dose for stoss therapy from vitamin D2 liquid-filled capsules that do not contain propylene glycol. Computer systems should warn staff about excessive propylene glycol and the potential for renal toxicity with pediatric patients.

STATE DRUG TRACKING DATABASE HELPS PREVENT AN ERROR

Many states have been working to reduce prescription drug abuse, overdose, and misuse by enacting legislation to set up scheduled drug electronic tracking programs. Doctors and pharmacists can access the program database to prevent an individual from going from doctor to doctor to obtain controlled drugs. A report we received recently shows how these systems can also protect patients against medication errors.

A patient admitted during the night through the emergency department (ED) had a home medication list that included a Duragesic (fentanyl) 100 mcg patch, which was circled to be continued on admission. Upon checking the state prescription database to verify that the patient was receiving 100 mcg regularly, the pharmacist noticed that the patient had not filled a prescription for the patches in the past 4 months. After confirming with the ED nurse that the patient was not currently wearing a patch, the pharmacist did not feel comfortable dispensing the pain medi-cation because it had not been used in months, meaning the patient was essentially opioid naïve. The pharmacist entered a note to “clarify home med,” and the hospitalist discontinued the order for the patch. Of note, the patient went to surgery the next day and the home medication list was printed. Unfortunately, the pharmacist and hospitalist who knew the fentanyl patch was not a recent home medication did not delete or clarify the entry on the home medication list. The surgeon circled Duragesic patch on the home medication list to continue its use. The same pharmacist happened to receive the postoperative orders and, again, did not dispense the patch. The Duragesic patch was not continued upon discharge.

This is a great illustration of the safety potential in reviewing a state scheduled drug database when a new patient is admitted with a controlled substance prescription. This enabled the pharmacist to detect a potentially dangerous medication error.

WHERE DID THAT MEDICATION COME FROM?

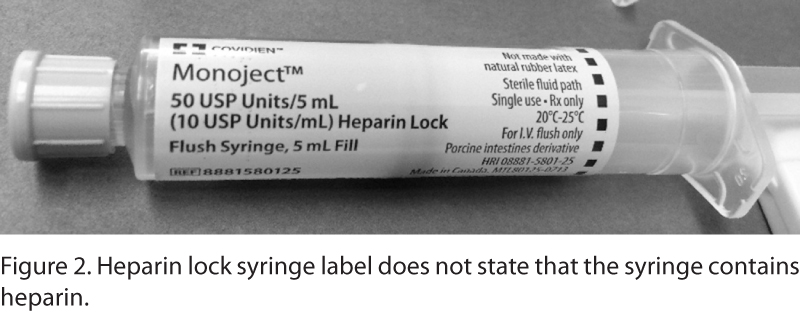

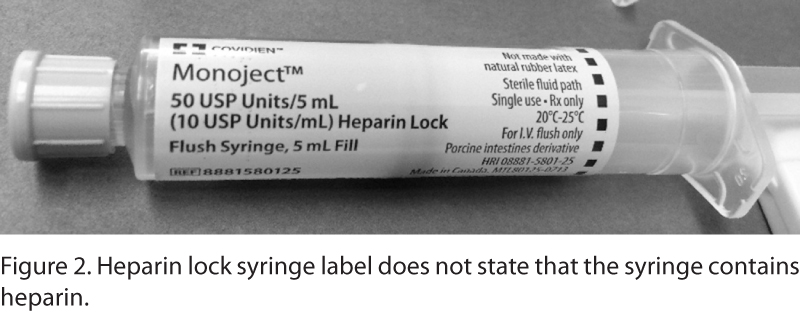

A hospital reported several occurrences in which medications not purchased or provided by the pharmacy made their way into the hospital supply, including on pharmacy shelves and in automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs). Recent examples include lidocaine ampuls that came from an IV line insertion kit and a heparin flush syringe brought from home by a patient’s family. Likewise, doctors sometimes bring unauthorized medications into the hospital to use for a patient. Safety is a concern when pharmacy has not assessed these medications for adequate labeling, expiration dating, look-alike/sound-alike names, or barcode-scanning capabilities. Nonformulary medications that have not been reviewed by a pharmacy and therapeutics committee also pose a risk.

Policies related to patients bringing medications from home should prevent patients’ use of these medications until they are identified by a pharmacist. These medications must be stored securely and never commingled with hospital floor stock medications. Pharmacists should work with the purchasing department to develop a list of manufacturer’s kits that contain medications. Before these are purchased, pharmacists should analyze their safety and test the barcodes for proper scanning when possible. Saving unused vials from manufacturer’s kits as floor stock should be prohibited, and nurses should be provided with clear directions regarding the disposition of leftover vials. Pharmacists and nurses should be alert to the risk of medications from external sources and look for these products during routine medication storage assessments.

Incidentally, the heparin flush syringe mentioned previously is labeled in a way that could have led to a medication error. It was not obvious that the syringe contained heparin flush solution, because “Monoject,” a trademark used for a line of syringes from Covidien, was most prominently noted on the label, not its heparin contents (Figure 2).

EXPIRATION DATE DIFFICULT TO READ

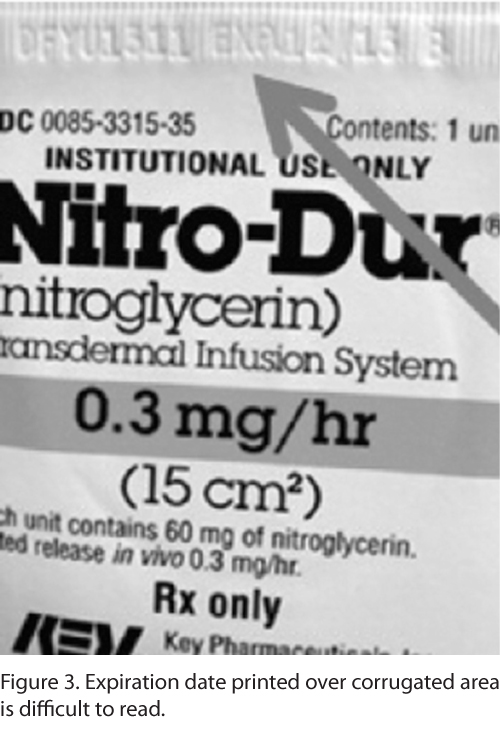

We’ve previously mentioned a situation in which a nurse used a lactulose product, by Pharmaceutical Associates, that was past its expiration date, because the lot number “2D15” looked more like 2015 next to the actual expiration date of “04/14” (04/14 2D15). Manufacturers have also used dates such as 15MAR14, which could be understood as March 14, 2015, or March 15, 2014, or the companies have abbreviated a month such as JN or MA 2014, which could be January or June, or May or March, respectively.

A pharmacist recently sent ISMP a Nitro-Dur (nitroglycerin) patch (Key Pharmaceuticals) (Figure 3) that has the lot number and expiration date embossed over a corrugated area that seals the protective paper outer wrap. This makes the date almost impossible to read and the numbers 3 and 5 difficult to distinguish. An illegible expiration date on a nitroglycerin patch can result in negative outcomes for cardiac patients.

ISMP has asked the FDA and the US Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) to ensure that manufacturers use specific expiration date formats that express dates in a uniform sequence to clearly communicate the date in a consistent and unambiguous manner. -Manufacturers should also avoid packaging features that might interfere with the legibility (eg, printing on shiny foil, corrugated areas, end seals on shrink-wrap). ![]()

*President, Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 200 Lakeside Drive, Suite 200, Horsham, PA 19044; phone: 215-947-7797; fax: 215-914-1492; e-mail: mcohen@ismp.org; Web site: www.ismp.org. ?Vice President, Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Horsham, Pennsylvania.