Perpetually Outraged, Perpetually Outrageous

Donald Trump, a candidate with all the subtlety of talk radio, is the perfect expression of both the politics and media of our time.

By Paul Waldman

If there’s a defining anecdote about Donald Trump in Michael D’Antonio’s Never Enough: Donald Trump and the Pursuit of Success, it comes when young Donald, then a high school student at the military academy where his demanding father sent him for being such an insufferable lout, sees his name in the newspaper for the first time. The occasion was a baseball game, and the headline read, “Trump Wins Game for NYMA.” The experience had a profound impact. “It felt good seeing my name in print,” Trump tells D’Antonio. “How many people are in print? Nobody’s in print. It was the first time I was ever in the newspaper. I thought it was amazing.” Not only did people know his name, they knew he was a winner.

Half a century later, Trump’s particular brand of fame and his unique persona positioned him extraordinarily well to run a presidential campaign in 2016. Political analysts who had grown tired of his previous flirtations with a presidential bid were shocked that he decided to run, and even more shocked when he went straight into the lead. But the political moment and the media moment had combined to give Trump the best opportunity he could ever have.

To understand Trump’s rise, you have to understand both those political and media moments. In many ways, Trump’s candidacy is the natural outgrowth of the Tea Party era. The Republican revolt that began once Barack Obama was elected president was full of rage and resentment (and notably, Trump made himself America’s most prominent birther, promising he’d get to the bottom of Obama’s foreign provenance). But the movement soon shifted the target of its rage from Obama to the Republican establishment, those ineffectual cowards on Capitol Hill who always failed to deliver to the base what they promised. Throughout, the conservative media outlets described by Jeffrey Berry and Sarah Sobieraj in The Outrage Industry: Political Opinion Media and the New Incivility egged on the insurgents, convincing them that the problem, even more so than usual, was Washington insiders. Then along came Trump, the ultimate outsider.

Trump is not just unsullied by ever having run for office, much less ever having held one; he’s also unlike ordinary politicians. For all we worry about negative campaigning, politicians usually talk about each other with a veneer of politeness and civility even when they are being harshly critical. They seldom come out and say, “That Jack Smith is a low-down dirty dog,” preferring to note that “my opponent’s behavior raises serious questions about whether he could represent this state in an ethical fashion.” Trump has no inhibitions. He’s more than happy to toss personal insults at anybody he doesn’t like. Lindsey Graham? “What a stiff.” Charles Krauthammer? “A totally overrated clown.” Mexican immigrants? “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” Carly Fiorina? “Look at that face! Would anyone vote for that?”

But you know who Donald Trump does sound like? A talk radio host, a member of that Outrage Industry. As Berry and Sobieraj describe it, Outrage has become its own media genre, one that “involves efforts to provoke emotional responses (e.g., anger, fear, moral indignation) from the audience through the use of overgeneralizations, sensationalism, misleading or patently inaccurate information, ad hominem attacks, and belittling ridicule of opponents.” Though hardly new in American politics, only in recent years has Outrage matured into such a core part of the media world.

While it may be aided by political polarization, the Outrage Industry is a media phenomenon, one that feeds and is fed by politicians, advocacy organizations, and political movements, none more so than the Tea Party. To satisfy the industry, its practitioners must be both perpetually outrageous and perpetually outraged.

How does all this affect us? As Diana Mutz notes in In-Your-Face Politics: The Consequences of Uncivil Media, the political interactions we see played out today are profoundly different from the way we confront the subject in our own lives. “Political discourse on television regularly violates norms for polite conversation,” she notes, because we tend to be polite to one another—and we usually avoid arguing about politics with people we know (except perhaps at Thanksgiving). “With political television, in contrast, there is considerable (if not incessant) political disagreement, and the opinion holders that we see and hear are often chosen specifically as exemplars of extremely divergent, highly polarized positions.”

You might say the same about all kinds of entertainment—most of us don’t engage in gunfights, fall in love with alarmingly beautiful people, or go on trial for murders we didn’t commit, but we watch these things in entertainment media all the time. Mutz conducts a series of carefully crafted experiments to tease out what happens to us when we watch hostile political argument, and finds a mixed bag of effects on arousal, memory, and perceptions of who’s being civil and who isn’t. Not all those effects are negative; for instance, in some cases the angrier exchanges are remembered better than the civil ones.

And the producers of cable news can take heart from Mutz’s work that they’re on the right track, because the subjects in her experiments rated uncivil debates as more entertaining than civil ones. For all our idealistic ideas about noble Athenian debate, “it is difficult to imagine a calm exchange of political ideas going viral. When it comes to uncivil outbursts, however, they are emailed, posted, and rebroadcast with commentary elsewhere.”

A few decades ago, American politics and the news media didn’t give vent to nearly as much harsh and hostile talk as they do today. There’s not much reason to believe that we as a people have become angrier than we were then. But never has anger had so many places to be amplified and spread. The first significant date in that evolution is 1987, when the Federal Communications Commission revoked the Fairness Doctrine, which had required holders of broadcast licenses to give equal time to opposing political viewpoints (generally presented, however, in a polite, even bland way). The end of the Fairness Doctrine led to an explosion of political talk radio, as station owners no longer had to worry about whether their offerings were balanced. Then in 1996, the Telecommunications Act loosened ownership limits, leading to a rapid consolidation in the radio industry. “There are now around 3,800 all-talk or all-news stations in the United States,” Berry and Sobieraj note, “roughly triple the number in existence before the dramatic wave of regulatory and technological shifts.”

As talk radio was expanding, it had (and still has) no bigger star than Rush Limbaugh, who did more than anyone else to ensure that this newly powerful medium would be dominated by the right. Success breeds imitation, and Limbaugh’s success convinced the industry that conservative talk was a surefire moneymaker. Liberal attempts to provide a radio counterweight haven’t been nearly as successful, in part because opinion radio isn’t filling the same need for liberals. Conservatives gravitate to talk radio in part because they’re convinced the mainstream media are biased against them—a core part of conservative ideology for years. Liberals also have popular alternatives they find appealing, including National Public Radio and stations catering to African Americans and Hispanics. Finally, there is plenty of research suggesting that conservatives are more drawn to the kind of black-and-white rhetoric that flourishes on talk radio than liberals are.

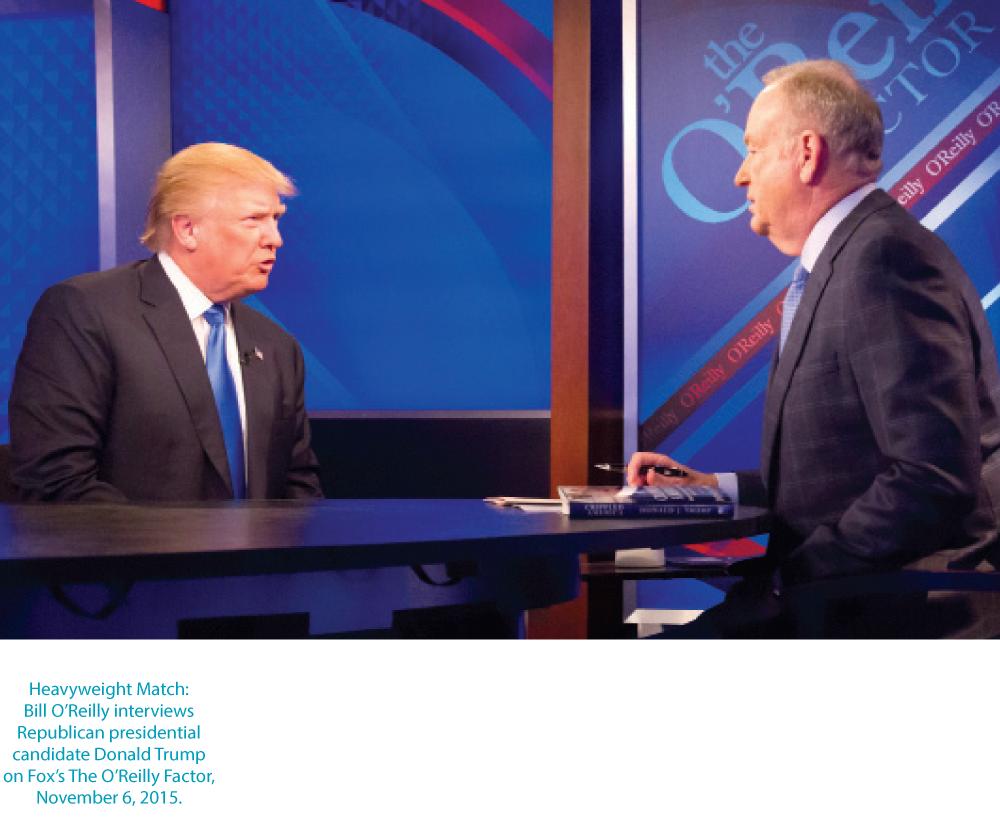

As talk radio grew, cable news came into its own, and the Internet began its rapid spread, Americans faced a newly fragmented media that allowed the Outrage Industry to develop. In this new landscape, it was no longer necessary to appeal to everyone—you could be a success with a much more limited audience, and that meant not worrying about the huge swaths of the population likely to be offended. The O’Reilly Factor, a prototypical Outrage program, is the top show on cable news, but only has around two million to three million viewers per night.

People may have looked to Walter Cronkite for the truth, but they look to Limbaugh or O’Reilly for what Stephen Colbert so memorably called “truthiness.” It’s not a literal, factual truth so much as it is an emotional truth that resonates with you. And Outrage resonates, Berry and Sobieraj argue. “It works because its coarseness and emotional pull offer the ‘pop’ that breaks through the competitive information environment, and it works because it draws on so many of our existing cultural touchstones: celebrity culture, reality television, a two-party system, as well as the conventional news and opinion to which those in the United States have become accustomed.”

These programs offer a kind of wish fulfillment, as you see yourself reflected in your favorite host. Performers like O’Reilly and Limbaugh channel their audiences’ rage and express it with more coherence and brio than that audience ever could on its own. When you curl your lip in disgust at President Obama or Lena Dunham or just some radical professor somewhere who is the target of Bill’s venom that night, you can be sure that O’Reilly will give them the smackdown they deserve. All that remains is for you to shout, “You tell ’em, Bill!” at the screen.

Talk radio and television hosts are in many ways the people their audiences wish they themselves could be: just like them, but better. They share the audience’s values and beliefs, but they’re a little smarter, a little better informed, and a lot more articulate (talking into a microphone for hours every day will do that). They say all the things you’d say if you could, and they say them better than you ever would.

Trump too presents an aspirational picture for his supporters, one that his critics may not quite appreciate. Educated, sophisticated liberals scorn him for his nouveau-riche boorishness, his eagerness to slap his name in 20-foot-high letters on everything he owns, his insistence on the most garish displays of wealth he can conjure up (why wouldn’t you decorate your penthouse with Roman columns?). There are plenty of super-rich who flaunt their wealth with grand boats and cars and homes, but no one who does it with quite the vulgarity Trump does, as though he were enacting a poor person’s idea of what a rich person is like.

This performance is an essential part of his appeal. Surveys consistently show Trump doing far better among blue-collar Republicans than among white-collar Republicans. If I had a billion dollars, many of his fans say, that’s just how I’d be: I’d put my name on my plane, get myself a hundred solid-gold toilets, trade in one fashion-model wife for a younger, prettier model as soon as she hits her forties, and tell everyone how successful and rich and better than them I am. I’d be a winner.

And it isn’t just in his personal style; it’s also in his political persona. Trump is not just competitive conspicuous consumption taken to its parodic extreme; he’s also unfailingly literal where any other politician—even any other human being—wouldn’t dare, for fear of sounding like something between a narcissist and a fool. Other politicians supply evidence—their experience, their ideas, their accomplishments—to lead you to an unspoken conclusion. Trump dispenses with the evidence and skips straight to the conclusion: Elect me, because I’m the best. “We will have so much winning when I get elected,” he says, “you will get bored with winning.”

And when he says that we’re being led by idiots, or that he’ll go to China and practically punch them in the nose until they give us our jobs back, or that we just need to build a wall along the border with Mexico, he offers the same kind of validation that talk radio hosts do. He says, you’re right about everything, those other people are idiots and jerks, and all those things you feel but think you shouldn’t say in polite company? I’ll say them for you!

This provides a way to understand Trump’s comments on immigrants—both the horror with which they were received in polite company and the burst of support in the polls that followed. As Berry and Sobieraj make clear, it’s nearly impossible to overstate the degree to which conservatives have become convinced that speaking out in public will get them unfairly branded as racist by liberals. And it’s certainly true that that does happen on occasion. But it’s also true that in the age of Obama, conservative media have been absolutely saturated with thinly (and not-so-thinly) veiled race-baiting from the likes of Limbaugh and Glenn Beck, who have spent years telling their almost entirely white audiences that Obama is a presidential version of Stokely Carmichael, a radical black nationalist out to wreak vengeance upon them for the racial sins of their ancestors.

On race, Trump can be a conservative champion, unafraid to make racially charged remarks and unapologetic when he does. One day he says Mexican immigrants are criminals and rapists, and the next he says, “I think I’ll win the Hispanic vote.” He’s not just wrong, but spectacularly wrong—in August, Gallup measured his approval among Hispanics at 14 percent—but he doesn’t seem to care. He’s speaking for conservatives on both ends, giving voice to their ugliest feelings and dismissing as absurd the idea that his statements might suggest any racism.

Once again, just like the leading lights of the Outrage Industry, Trump is the person his fans wish they could be. Those surprised by his rapid success in the polls might have missed the fact that as buffoonish as he might appear to some, Trump is a skilled entertainer who has been honing his portrayal of the character known as “Donald Trump” for decades, but particularly since The Apprentice debuted in 2004. Just like other conservative media figures, the character is a version of the real person, exaggerated for the benefit of the cameras. In the same way, O’Reilly goes on Fox News every weeknight and performs as a character named Bill O’Reilly. Is that character “real”? Yes and no. He surely believes what he says, and plenty of testimony from those who have known him show him to actually be an overbearing bully. But the televised version creates a persona out of the person by amping it up to an extreme.

In his private moments, is Trump the same person? Perhaps he brushes his teeth in the morning, then looks in the mirror and proclaims: “That was the classiest, most luxurious brushing any set of teeth have ever experienced. I mean, it’s incredible.” One imagines that moving through life in an endless parade of superlatives would be extraordinarily tiring. But the Trump we see in the media is, to the public, the only reality that matters.

Trump’s combination of wealth and fame may not quite make him “quite literally, the face of modern success,” as D’Antonio says. But even the things for which he is ridiculed only reinforce what a perfect creature of the moment Trump is. His Twitter feed is like a piece of cultural and political performance art, a running flame war not just with his fellow candidates but with the likes of Cher and Bette Midler. He’s at once spectacularly arrogant, extraordinarily thin-skinned, and desperate for attention—an embodiment, or perhaps an exaggeration, of the way a nation of over-sharers represents itself in contemporary social media.

American politics didn’t use to feature running flame wars. Like Berry and Sobieraj, Mutz doesn’t believe the politicians themselves are any less civil now than they used to be. But as she notes, nobody watched Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton duel on YouTube.

If something similar happened today, you bet we’d watch it, over and over again. And even if his ability to get people to actually vote for him has its limits, we can’t stop watching Trump—rich guy, tabloid celebrity, reality TV host, and purveyor of insults and outrage. He might not be popular enough to become president, but at this moment in history, he’s pure media gold. ![]()

Paul Waldman is the Prospect’s senior writer and weekly columnist. He also writes for The Week and the Plum Line blog at The Washington Post. He is the author of Being Right Is Not Enough: What Progressives Must Learn from Conservative Success.