A Case of Pelvic Organ Prolapse in the Setting of Cirrhotic Ascites

Nima M. Shah, MD, Natasha Ginzburg, MD, Kristene Whitmore, MD

Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Ascites is commonly found in patients with liver cirrhosis. Although conservative therapy is often the ideal choice of care with these patients who also have symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, this may fail and surgical methods may be needed. Literature is limited regarding surgical repair of prolapse in the setting of ascites. The authors present the surgical evaluation and management of a 63-year-old woman with recurrent ascites from liver cirrhosis who failed conservative therapy. With adequate multidisciplinary care and medical optimization, this patient underwent surgical therapy with resolution of her symptomatic prolapse and improved quality of life.

[Rev Urol. 2016;18(3):178-180 doi: 10.3909/riu0702]

© 2016 MedReviews®, LLC

A Case of Pelvic Organ Prolapse in the Setting of Cirrhotic Ascites

Nima M. Shah, MD, Natasha Ginzburg, MD, Kristene Whitmore, MD

Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Ascites is commonly found in patients with liver cirrhosis. Although conservative therapy is often the ideal choice of care with these patients who also have symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, this may fail and surgical methods may be needed. Literature is limited regarding surgical repair of prolapse in the setting of ascites. The authors present the surgical evaluation and management of a 63-year-old woman with recurrent ascites from liver cirrhosis who failed conservative therapy. With adequate multidisciplinary care and medical optimization, this patient underwent surgical therapy with resolution of her symptomatic prolapse and improved quality of life.

[Rev Urol. 2016;18(3):178-180 doi: 10.3909/riu0702]

© 2016 MedReviews®, LLC

A Case of Pelvic Organ Prolapse in the Setting of Cirrhotic Ascites

Nima M. Shah, MD, Natasha Ginzburg, MD, Kristene Whitmore, MD

Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Ascites is commonly found in patients with liver cirrhosis. Although conservative therapy is often the ideal choice of care with these patients who also have symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, this may fail and surgical methods may be needed. Literature is limited regarding surgical repair of prolapse in the setting of ascites. The authors present the surgical evaluation and management of a 63-year-old woman with recurrent ascites from liver cirrhosis who failed conservative therapy. With adequate multidisciplinary care and medical optimization, this patient underwent surgical therapy with resolution of her symptomatic prolapse and improved quality of life.

[Rev Urol. 2016;18(3):178-180 doi: 10.3909/riu0702]

© 2016 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Ascites • Cirrhosis • Prolapse • Colpocleisis

Key words

Ascites • Cirrhosis • Prolapse • Colpocleisis

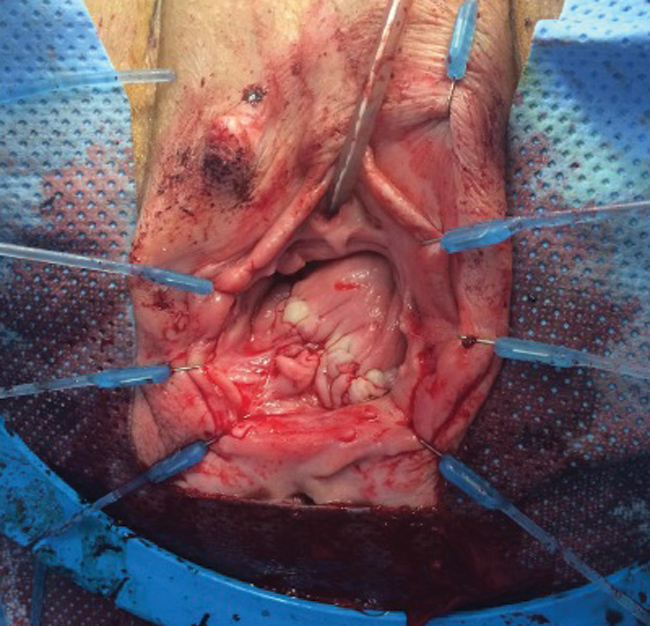

Figure 1. Preoperative image of uterovaginal prolapse with ulcerations.

Figure 2. Preoperative image of uterovaginal prolapse with ulcerations.

Utilizing monitored anesthetic care, moderate sedation, pudendal block, and local anesthetic, she underwent a cystoscopy, colpocleisis, enterocele repair, augmentation with dermis graft, and perineorrhaphy.

It is known that the presence of ascites is associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure, and can increase tension on the abdominal wall with weakening of the abdominal fascia. Likely, this concept applies similarly to the pelvic floor and the endopelvic fascia.

Figure 3. Intraoperative closure via colpocleisis with underlying dermis graft.

Figure 4. Photo taken 1 month after surgical closure of uterovaginal prolapse via colpocleisis with underlying dermis graft.

Main Points

• Cirrhosis is the most common cause of ascites in the United States, accounting for approximately 85% of cases. Similarly, ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis in approximately 80% of cases. Although conservative therapy is often the ideal choice of care for patients who also have symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, this may fail and surgical methods may be needed.

• The presence of ascites is associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure, and can increase tension on the abdominal wall with weakening of the abdominal fascia. Likely, this concept applies similarly to the pelvic floor and the endopelvic fascia.

• Utilizing monitored anesthetic care, moderate sedation, pudendal block, and local anesthetic, this patient underwent a cystoscopy, colpocleisis, enterocele repair, augmentation with dermis graft, and perineorrhaphy.

• In this patient, colpocleisis was selected primarily because of its shorter operative time, low risk of perioperative morbidity, and low risk of prolapse recurrence. Polydioxanone sutures were used for the repair because of their duration of strength retention and delayed absorption, given the concern of the ascitic fluid providing further pressure on the pelvic floor during the recovery period. A dermis graft was used in an attempt to decrease the risk of recurrence, as has been demonstrated in anterior compartment prolapse.

Main Points

• Cirrhosis is the most common cause of ascites in the United States, accounting for approximately 85% of cases. Similarly, ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis in approximately 80% of cases. Although conservative therapy is often the ideal choice of care for patients who also have symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, this may fail and surgical methods may be needed.

• The presence of ascites is associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure, and can increase tension on the abdominal wall with weakening of the abdominal fascia. Likely, this concept applies similarly to the pelvic floor and the endopelvic fascia.

• Utilizing monitored anesthetic care, moderate sedation, pudendal block, and local anesthetic, this patient underwent a cystoscopy, colpocleisis, enterocele repair, augmentation with dermis graft, and perineorrhaphy.

• In this patient, colpocleisis was selected primarily because of its shorter operative time, low risk of perioperative morbidity, and low risk of prolapse recurrence. Polydioxanone sutures were used for the repair because of their duration of strength retention and delayed absorption, given the concern of the ascitic fluid providing further pressure on the pelvic floor during the recovery period. A dermis graft was used in an attempt to decrease the risk of recurrence, as has been demonstrated in anterior compartment prolapse.

A 63-year-old woman was referred to us by her transplant hepatologist to evaluate the complaint of vaginal prolapse status associated with severe pain and vaginal ulcerations. after total hysterectomy. She reported in the previous weeks her prolapse had completely descended, causing significant discomfort. She admitted to urinary frequency associated with chronic diuretic use. She denied bowel symptoms, incontinence, or dysuria. She reported not being sexually active for “years” because of her health issues, as well as her husband’s erectile dysfunction. On examination, she had stage 4 procidentia with two large and multiple small ulcers (Figures 1 and 2). She was started on topical vaginal estrogen. The extent of her mucosal ulcerations eliminated pessary use and conservative therapy.

Her obstetric history consisted of three vaginal deliveries. Her medical history was significant for alcohol-induced and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis. She was diagnosed 11 months earlier while hospitalized for a perforated duodenal ulcer. During the exploratory laparotomy, advanced liver disease was identified. Postoperatively, her course was complicated by acute renal failure, worsening liver disease secondary to sedative use, refractory ascites requiring biweekly paracentesis with subsequent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, splenomegaly, and sacral decubitus ulcer. After a prolonged recovery, she was placed on the liver transplant list. Her most recent Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score was 10.

Surgical options were discussed, and with the patient’s history of recurrent ascites and lack of sexual activity, both the patient and surgeon agreed to proceed with colpocleisis and possible use of a dermis graft. The patient was medically optimized for her procedure. Preoperatively, she underwent paracentesis with removal of 7 L of ascites. Her liver profile, coagulation, and hematology panel results were within normal limits. Utilizing monitored anesthetic care, moderate sedation, pudendal block, and local anesthetic, she underwent a cystoscopy, colpocleisis, enterocele repair, augmentation with dermis graft, and perineorrhaphy. Her colpocleisis was performed in the usual manner; however, excess vaginal mucosa was left behind until the dermis graft was placed. After imbrication of the prolapse, the enterocele was repaired via an extraperitoneal, high uterosacral ligament suspension with polydioxanone (PDS) sutures. The dermis graft was then placed along the pubocervical fascia, and secured to the sacrospinous ligament, iliococcygeus and rectovaginal septum with PDS sutures. At that point, the excess vaginal mucosa was trimmed to cover the dermis graft, and reapproximated with vicryl suture (Figure 3). Multiple vaginal varicosities were also noted during the dissection. Postoperatively, the transplant surgery team cared for the patient concurrently and she was discharged on postoperative day 3 after completing a paracentesis on the day of discharge.

Discussion

Cirrhosis is the most common cause of ascites in the United States, accounting for approximately 85% of cases. Similarly, ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis in approximately 80% of cases. Patients with ascites can develop complications including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hydrothorax, and umbilical hernias. There is limited literature regarding pelvic organ prolapse and ascites. Davis and Carroccio1 reported the case of a 21-year-old nulliparous woman who underwent anterior repair (sacrospinous cervicopexy) for massive uterovaginal prolapse with chronic ascites. Ward and Rardin2 presented a case of a middle-aged woman with enterocele and incidental chylous ascites during posterior repair. It is known that the presence of ascites is associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure, and can increase tension on the abdominal wall with weakening of the abdominal fascia. Likely, this concept applies similarly to the pelvic floor and the endopelvic fascia.

Upon reduction of the patient’s vaginal vault prolapse, she did not appear to have a significant anterior or posterior defect. The primary defect appeared to be the vaginal vault secondary to the enterocele. We believe the patient’s massive ascites was an exacerbating factor, especially given the size of the prolapse. Colpocleisis was selected primarily because of its shorter operative time, low risk of perioperative morbidity, and low risk of prolapse recurrence.3 PDS sutures were used for the repair because of their duration of strength retention and delayed absorption given the concern of the ascitic fluid providing further pressure on the pelvic floor during the recovery period. We used a dermis graft in an attempt to decrease the risk of recurrence, as has been demonstrated in anterior compartment prolapse.4 After surgery, the patient reported significant relief of her pressure and pain symptoms. She continued twice-weekly paracentesis given her ascites accumulation and had approximately 3 to 7 L drained each time. Her liver panel and other laboratory test results have remained stable. She is currently being followed at the outpatient office and continues to meet postoperative milestones. Figure 4 shows results at her 1-month postoperative visit. Subjectively, she has reported increased physical activity, including walking and other exercise.

Conclusions

Patients with significant medical comorbidities may also have symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. In these patients, conservative management is not always successful. Although prolapse reduction surgery may be considered elective, it is important to evaluate patient symptoms, and their effects on quality of life. The best choice for this patient was the safest procedure available that provided a high success rate. Additionally, given the complexity of her medical issues, it was important to include all providers in her care. As the symptomatic prolapse patient population increases, further medical comorbidities will arise and we can continue to optimize these patients’ care with a multidisciplinary approach. ![]()

References

- Davis JD, Carroccio S. Massive uterovaginal prolapse in a young nulligravida with ascites: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:727-729.

- Ward RM, Rardin CR. Chylous ascites presenting as an enterocele. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:553-555.

- Mueller MG, Ellimootil C, Abernethy MG, et al. Colpocleisis: a safe, minimally invasive option for pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21:30-33.

- Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD004014.