Conservative Management of Urinary Incontinence in Women

Izak Faiena, MD, Neal Patel, MD, Jaspreet S. Parihar, MD, Marc Calabrese, BA, Hari Tunuguntla, MD

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ

Urinary incontinence in women has a high prevalence and causes significant morbidity. Given that urinary incontinence is not generally a progressive disease, conservative therapies play an integral part in the management of these patients. We conducted a nonsystematic review of the literature to identify high-quality studies that evaluated the different components of conservative management of stress urinary incontinence, including behavioral therapy, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle training, lifestyle changes, mechanical devices, vaginal cones, and electrical stimulation. Urinary incontinence can have a severe impact on our healthcare system and patients’ quality of life. There are currently a wide variety of treatment options for these patients, ranging from conservative treatment to surgical treatment. Although further research is required in the area of conservative therapies, nonsurgical treatments are effective and are preferred by some patients.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(3):129-139 doi: 10.3909/riu0651]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Conservative Management of Urinary Incontinence in Women

Izak Faiena, MD, Neal Patel, MD, Jaspreet S. Parihar, MD, Marc Calabrese, BA, Hari Tunuguntla, MD

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ

Urinary incontinence in women has a high prevalence and causes significant morbidity. Given that urinary incontinence is not generally a progressive disease, conservative therapies play an integral part in the management of these patients. We conducted a nonsystematic review of the literature to identify high-quality studies that evaluated the different components of conservative management of stress urinary incontinence, including behavioral therapy, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle training, lifestyle changes, mechanical devices, vaginal cones, and electrical stimulation. Urinary incontinence can have a severe impact on our healthcare system and patients’ quality of life. There are currently a wide variety of treatment options for these patients, ranging from conservative treatment to surgical treatment. Although further research is required in the area of conservative therapies, nonsurgical treatments are effective and are preferred by some patients.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(3):129-139 doi: 10.3909/riu0651]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Conservative Management of Urinary Incontinence in Women

Izak Faiena, MD, Neal Patel, MD, Jaspreet S. Parihar, MD, Marc Calabrese, BA, Hari Tunuguntla, MD

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ

Urinary incontinence in women has a high prevalence and causes significant morbidity. Given that urinary incontinence is not generally a progressive disease, conservative therapies play an integral part in the management of these patients. We conducted a nonsystematic review of the literature to identify high-quality studies that evaluated the different components of conservative management of stress urinary incontinence, including behavioral therapy, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle training, lifestyle changes, mechanical devices, vaginal cones, and electrical stimulation. Urinary incontinence can have a severe impact on our healthcare system and patients’ quality of life. There are currently a wide variety of treatment options for these patients, ranging from conservative treatment to surgical treatment. Although further research is required in the area of conservative therapies, nonsurgical treatments are effective and are preferred by some patients.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(3):129-139 doi: 10.3909/riu0651]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Urinary incontinence • Women • Conservative management

Key words

Urinary incontinence • Women • Conservative management

There are typically three components to bladder training: patient education, scheduled voiding, and positive reinforcement.

Obesity is a significant modifiable and reversible risk factor for SUI. Obesity has been hypothesized to promote UI by increasing intra-abdominal pressure leading to chronic stress on the pelvic floor.

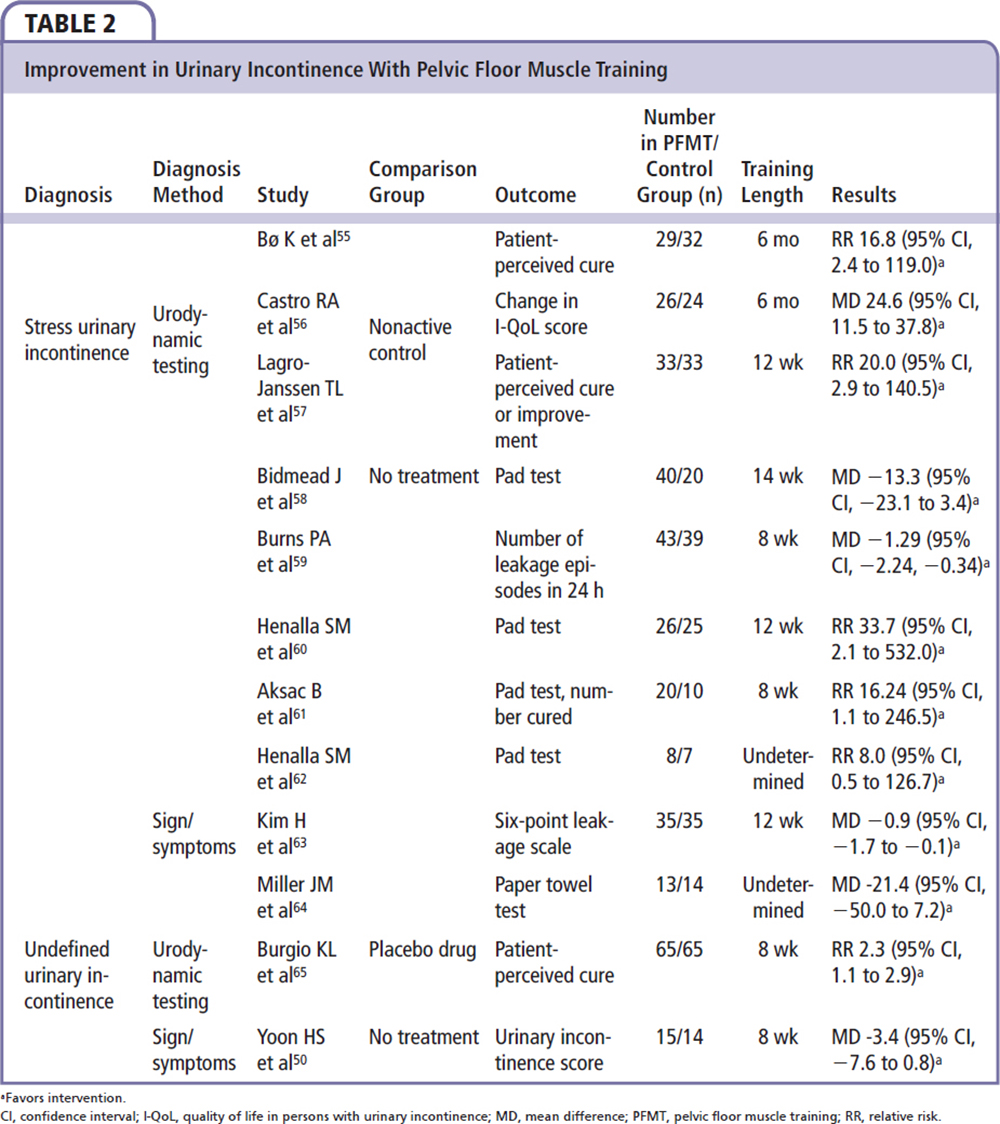

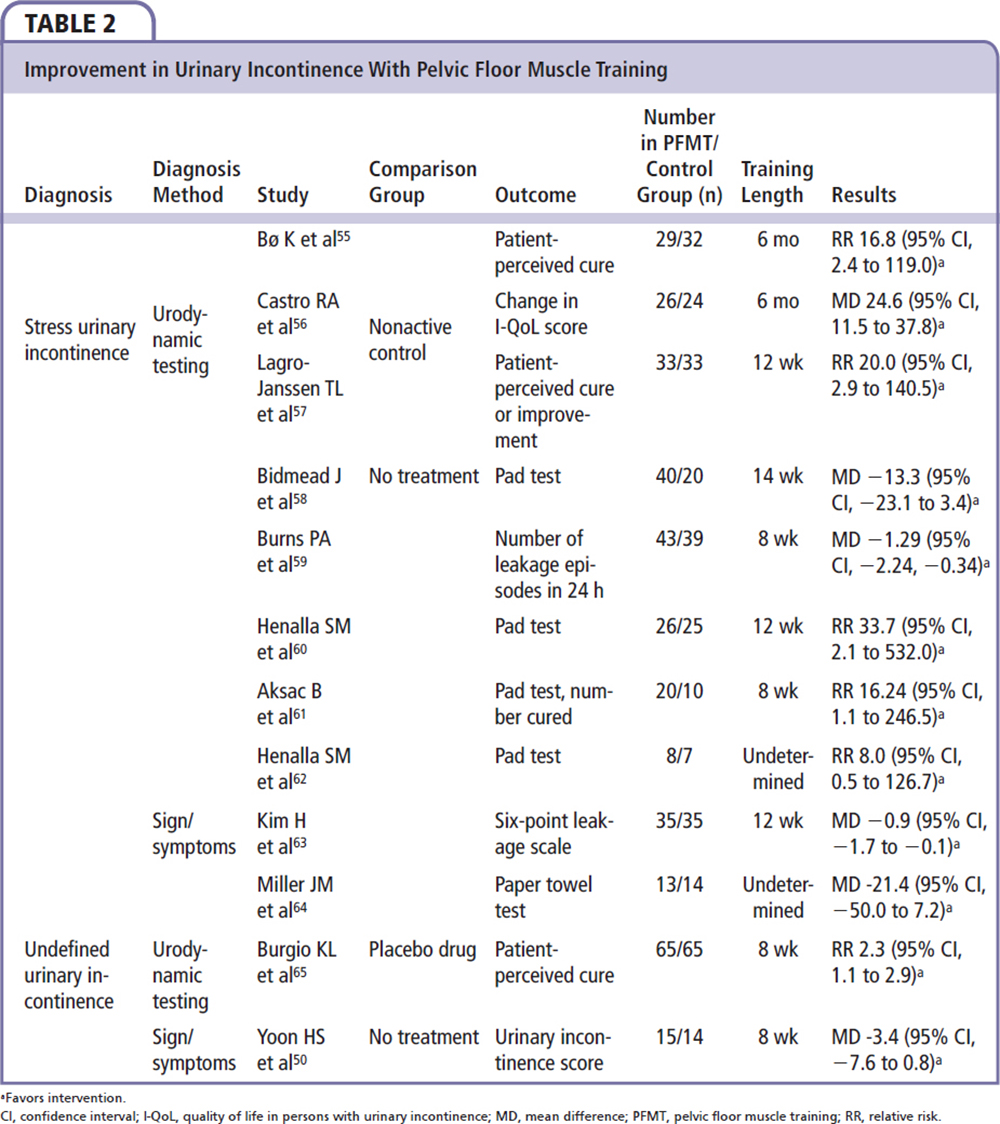

… women who underwent PFMT were more likely to have fewer daily episodes of leakage and a better reported quality of life, and were more likely to report an improvement or cure.

Although urethral inserts are potentially applicable to almost all women with pure SUI, the fact that these devices must be removed and reinserted with each void is not attractive to most women.

Main Points

• Urinary incontinence (UI) in women has a high prevalence and causes significant morbidity. Given that urinary incontinence is not generally a progressive disease, conservative therapies, including behavioral therapy, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle training, lifestyle changes, mechanical devices, vaginal cones, and electrical stimulation, play an integral part in the management of these patients.

• Bladder training is a commonly used technique for patients with overactive bladder or urgency UI. There are usually three components to bladder training: patient education, scheduled voiding, and positive reinforcement. The aim of this technique is to have the patient void prior to urgency and UI. The ultimate goal is a comfortable interval between voids with continence—a retraining of the bladder.

• Patient-perceived cures were more likely reported after pelvic floor muscle training, especially in patients with stress UI.

• Pessaries, which work by providing mechanical support for the urethra, have been used for the treatment of stress UI. Some potential advantages of these vaginal support devices are that they can potentially be applicable to the majority of the incontinent population, they have mild side effects, and they don’t require any specific testing.

• Another treatment option for UI in women is the use of intravaginal pelvic floor electrostimulation devices. These devices are also known for their low side-effect profile, which includes only burning or irritation at very high intensities. The mechanism of action for this modality relies on the electrical stimulation to induce hypertrophy of skeletal pelvic floor muscles via reflex contractions, while activating the detrusor inhibitory reflex arc.

Main Points

• Urinary incontinence (UI) in women has a high prevalence and causes significant morbidity. Given that urinary incontinence is not generally a progressive disease, conservative therapies, including behavioral therapy, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle training, lifestyle changes, mechanical devices, vaginal cones, and electrical stimulation, play an integral part in the management of these patients.

• Bladder training is a commonly used technique for patients with overactive bladder or urgency UI. There are usually three components to bladder training: patient education, scheduled voiding, and positive reinforcement. The aim of this technique is to have the patient void prior to urgency and UI. The ultimate goal is a comfortable interval between voids with continence—a retraining of the bladder.

• Patient-perceived cures were more likely reported after pelvic floor muscle training, especially in patients with stress UI.

• Pessaries, which work by providing mechanical support for the urethra, have been used for the treatment of stress UI. Some potential advantages of these vaginal support devices are that they can potentially be applicable to the majority of the incontinent population, they have mild side effects, and they don’t require any specific testing.

• Another treatment option for UI in women is the use of intravaginal pelvic floor electrostimulation devices. These devices are also known for their low side-effect profile, which includes only burning or irritation at very high intensities. The mechanism of action for this modality relies on the electrical stimulation to induce hypertrophy of skeletal pelvic floor muscles via reflex contractions, while activating the detrusor inhibitory reflex arc.

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a significant cause of decrease in quality of life, especially among women.1 The prevalence of UI in women is estimated to range from 13% to 46%,2,3 and studies have shown that incontinence increases with age.4 In addition to the significant social impact that UI has on a woman’s quality of life, this condition has a significant financial burden on individual and national healthcare dollars. It has been estimated that the total annual direct and indirect cost for UI in the United States alone is $19.5 billion.5

UI is defined according to patients’ symptoms. Although definitions vary in the literature, the International Continence Society defines three major subtypes of UI: (1) stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is the complaint of involuntary leakage on effort or exertion, or on sneezing or coughing; (2) urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is the complaint of involuntary leakage accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency; and (3) mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) is the complaint of involuntary leakage associated with urgency and also with exertion, effort, sneezing, or coughing.6,7

Although there is a plethora of treatment options, conservative management is the first-line option for most patients with UI. The rationale for conservative treatment is that UI is not necessarily a progressive disease, and that conservative therapies can be effective, well tolerated, and safe. Furthermore, a moderate delay in surgical therapy does not make treatment more difficult or less effective. One of the recommendations of the 1992 Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guideline states that “surgery, except in very specific cases, should be considered only after behavioral and pharmacologic interventions have been tried.”8 Similarly, the European Association of Urology guidelines advocate a stepwise approach regarding management of UI, which begins with addressing underlying medical or cognitive issues, progressing to lifestyle modifications, behavioral therapy, and mechanical devices.9 In addition, conservative therapies are frequently preferred by many patients. Taking into account the patient’s goals and preferences, it is appropriate to recommend conservative management as an initial approach.

Methods

We conducted a nonsystematic review of the literature using the PubMed database. Using the free-text protocol, the search term urinary incontinence plus the terms conservative management, behavioral therapy, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle training, lifestyle changes, mechanical devices, vaginal cones, and electrical stimulation were entered across the title and abstract fields from 1980 to 2014. Four authors reviewed these results. Only English language articles were considered. For each parameter, preference was given to Cochrane reviews, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses that were available in the literature. When the prior mentioned literature was unavailable, the largest series with the longest follow-up were included in this study. Additionally, other significant studies were identified using the reference lists of the selected papers.

Behavioral Therapy

Behavioral therapy describes a group of treatments aimed at educating the incontinent female patient about her condition and providing the patient with strategies to reduce incontinence. There are several components that fall under the rubric of behavioral therapy. Each individual element of behavioral therapies discussed here is centered on basic educational techniques such as operant learning, which is intended to model activity to reproduce normal behavior (in this case UI).10

Bladder Training

Bladder training is a commonly used technique for patients with overactive bladder (OAB) or UUI. There are typically three components to bladder training: patient education, scheduled voiding, and positive reinforcement. The aim of this technique is to have the patient void prior to urgency and UI. This interval is then gradually increased with clinical improvement. In conjunction with timed voiding, fluid management, bladder diaries, urge inhibition techniques, and anticholinergic medical therapy are added. Timed voiding has been explored and there is insufficient evidence to recommend it as a singular intervention.11 The ultimate goal is a comfortable interval between voids with continence—a retraining of the bladder. The International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) makes a grade A recommendation, based on level 1 evidence that “bladder training is recommended as a first-line treatment of UI in women.”12

A recent Cochrane review13 of bladder training for UI found 12 trials with a total of 1473, predominantly female, participants. Three trials compared bladder training with no bladder training. Results generally favored bladder training; however, there were no statistically significant differences found in the primary endpoints, which varied among the trials. Three trials compared bladder training with drugs: two with oxybutynin and one with imipramine plus flavoxate. In the first two trials, participants’ perception of cure at 6 months (relative risk [RR] 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.21-2.34), quality of life, and adverse events were statistically significant in favor of bladder training, and the number of daytime micturitions per week favored drug treatment. In the latter trial, participants’ perception of cure immediately after treatment just achieved statistical significance (RR 1.50; 95% CI, 1.02-2.21) in favor of bladder training, and this difference was maintained at approximately 2 months after treatment. Two comparisons of bladder training with pelvic floor muscle training plus biofeedback showed no difference.

Overall, the conclusion was that there is limited evidence suggesting that bladder training is helpful for the treatment of UI; however, there is not enough evidence to determine whether bladder training was a useful supplement to other therapies (Table 1).

Lifestyle Changes

Patient education regarding bladder health is also helpful in managing SUI and OAB. Healthy bladder habits include lifestyle modifications such as eliminating bladder irritants from the diet, managing fluid intake, weight control, managing bowel regularity, and smoking cessation.

Caffeine has been shown to have a diuretic effect,14 and has been shown to increase OAB symptoms by increasing detrusor pressure15 and by increasing detrusor muscle excitability.16 This is likely a dose-dependent event because it has been shown that high caffeine intake (> 400 mg/d average) correlated with urodynamic detrusor overactivity compared with stress-incontinent women (< 200 mg/d average).17 Although there is no strong evidence, there are some studies that do suggest that decreasing caffeine intake improves continence.18 Therefore, patients should be advised of adverse effects of caffeine on bladder health.

Fluid restriction has also been recommended in the treatment of both SUI and OAB, as excessive fluid intake can exacerbate symptoms of SUI and OAB. Physical stress occurring at lower bladder volumes is less likely to cause leakage, and will cause lower volume leakage if it does occur. Conversely, extreme fluid restriction produces concentrated urine, which has been postulated to be a bladder irritant, leading to frequency, urgency, and urinary tract infections.19 A baseline frequency-volume chart should be obtained and patients with normal to increased fluid intake should try moderately restricting fluid intake. The daily volume of fluid intake should be approximately six 8-oz glasses per 24 h (approximately 1500 mL or 30 mL/kg body weight per 24 h).20,21

In a study of constipation in geriatric hospital patients, the prevalence of constipation was directly correlated to SUI.22 Coyne and colleagues23 found higher rates of constipation in men and women with OAB compared with patients without OAB, based on patient-reported outcomes, which can also reflect treatment with anticholinergic agents in the OAB group. Treating constipation has been shown to significantly improve urgency and frequency in older patients.24 The ICI panel concluded that constipation and chronic straining may be a risk factor for the development of UI (level 3 evidence), but that there were no data to suggest that intervention was beneficial.

Obesity is a significant modifiable and reversible risk factor for SUI. Obesity has been hypothesized to promote UI by increasing intra-abdominal pressure leading to chronic stress on the pelvic floor.25 In a study examining the relationship of body mass index (BMI) to UI, Townsend and colleagues26 found that increased BMI and waist circumference both significantly increased the risk of UI (P < .001 for both). The same research group showed that not only was obesity a risk factor for UI, but also that weight gain was an independent risk for incident UI.27 Gaining 5 to 10 kg after age 18 years increased the risk of developing weekly UI by 44% (odds ratio [OR] 1.44; 95% CI, 1.05-1.97) compared with women who maintained their weight within 2 kg irrespective of their initial weight; gaining 30 kg increased the risk by fourfold. A prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Subak and associates28 studied 338 overweight and obese women at two centers in the United States. Subjects were randomized to an intensive 6-month weight loss program that included diet, exercise, and behavior modification, or to a structured education program. Results showed a statistically significant decrease for all UI (−47% vs −28%) and SUI (−58% vs −33%) in the weight loss group. Therefore, it is clear that obesity is a cause for UI and weight loss is an effective treatment that should be a first-line therapy for obese patients with UI (particularly those with SUI). In addition, there is evidence to suggest increasing level of physical activity reduces risk of SUI.29-31

Smoking has also been proposed as a risk factor for SUI by increasing coughing episodes,32 and for OAB through bladder irritation from nicotine and toxins excreted in the urine. However, to date, epidemiologic studies of tobacco use have produced inconsistent findings. In women, some studies suggest that smoking increases the risk of UI, or at least severe UI, but others demonstrate no increased risk. A 1-year longitudinal study of 6424 women over 40 years found that current smokers were at higher risk for both SUI and OAB compared with those who had never smoked, although statistical significance was seen only for those with OAB.33 Given the lack of adequate studies, the ICI committee could not make any evidence-based recommendation.12 Despite these conflicting results, smoking cessation should still be recommended as a general health measure, to reduce the risk of bladder cancer, and to reduce coughing episodes in smokers with UI.

Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) use began gaining popularity in the mid-20th century thanks to Arnold Kegel’s success in treating women with SUI. PFMT for treatment of SUI and MUI is thought to utilize pelvic floor muscles in three distinct ways: by increasing urethral pressure, through support of the bladder neck, and by interacting with the transversus abdominis via coordinated contractions between the pelvic floor muscles and the transversus abdominis. In the case of UUI, it is thought that pelvic floor muscle contraction can inhibit detrusor muscle contractions.34-36

A 2010 Cochrane review looked at 14 trials; of these, UI was diagnosed in 3 trials using signs and/or symptoms, whereas in 11 trials the diagnosis was confirmed using urodynamic testing.37 SUI, UUI, and MUI were evaluated. PFMT was taught by trained staff and strength and endurance training were both utilized as methods of PFMT. Strength was usually defined as low repetitions with higher load, whereas endurance (or fatigue resistance) was defined as higher repetition with lower loads. Behavioral training was also used to teach the subjects to perform voluntary contractions immediately prior to an event that may cause leakage. It was found that, after PFMT, a patient-perceived cure was more likely, especially in patients with SUI compared with MUI and UUI. It was also found that trials in which women trained longer (6 mo vs 6 to 8 wk) and those in which women were younger (mean age 50 y) reported higher cure rates. This review also found that women who were diagnosed with SUI by urodynamic testing were 17 times more likely to report a cure, compared with the 2 to 2.5 times likelihood of cure reported in women diagnosed with UUI via urodynamic testing. The authors concluded that women who underwent PFMT were more likely to have fewer daily episodes of leakage and a better reported quality of life, and were more likely to report an improvement or cure.37

In contrast to self-directed regimens, a clinician-guided PFMT program with regular supervision is recommended to ensure effectiveness.31 Biofeedback has also been explored with PFMT as a way to help women appreciate their muscle output during pelvic contraction. Studies have not found a significant difference in outcomes when adding biofeedback; however, it may be useful when initiating PFMT in order to better educate women on accurate pelvic contractions.38 A more recent Cochrane review explored the differences between different types of PFMT and explored the increasing role of biofeedback. Thirty-two reports from 15 studies were included in the final meta-analysis. This review looked at supervision of PFMT, content of the PFMT programs, frequency of training, and compliance with training.39 The review found that patients with more healthcare professional contact and patients who trained in group sessions were more likely to report a cure and improvement; however, the reviewers cautioned that this could be related to experimenter effect given the lack of blinding. This review also found that direct PFMT (voluntary pelvic floor contractions) training was better than sham training, and training 3 times a week, as well as adherence to the training regimen, was noted to be important, but few trials were unable to show a relationship of compliance and outcomes. Overall, this review found that use of direct PFMT with weekly supervision was optimal.39

Duloxetine has also been proposed as an effective pharmacotherapy. The mechanism of action appears to involve modulatory influence of serotonin and norepinephrine at urethral rhabdosphincter mediated by the Onuf’s nucleus in the sacral spinal cord.40 A large, multicenter RCT of 201 patients supported the efficacy of combining PFMT and duloxetine in the treatment of women with SUI.41 Although the drug was withdrawn in 2005 by the US Food and Drug Administration for its SUI indication due to liver toxicity and suicidal events, it is still available as a treatment option in Europe.30 In addition, in a recent clinical trial, women with SUI were randomized to PFMT versus initial midurethral sling placement; women with initial sling placement were found to have a significantly higher rate of subjective improvement at 91%, compared with 64% of women in the PFMT group, with an absolute difference of 26% (95% CI, 18.1-34.5) (Table 2).42

Vaginal Cones

In the treatment of SUI, first-line treatment tends to be PFMT. However, women may either have trouble identifying and controlling this group of muscles, or are just poorly compliant to the training and therefore other interventions need to be explored. Sets of graded weighted vaginal cones are the proposed solution to this dilemma. The cones provide progressive muscular overload. They are inserted into the vagina and the patient is instructed to maintain the heaviest cone possible within the vagina. Patients advance progressively to the use of heavier cones. This methodology is thought to allow for faster PFMT training, with perceived improvements that provide a motivational factor. A reasonable goal is to retain the cone for 20 minutes while walking.

In a Cochrane review by Herbison and Dean,43 23 small clinical trials were evaluated that compared vaginal cones with traditional PFMT, electrostimulation, and various combinations of these three treatment modalities. The study was unable to identify if combination therapy with vaginal cones was better or worse than single modality. However, it was found that vaginal cones may be better than no active treatment (RR 0.84; 95% CI, 0.76-0.94) and they may be a good conservative option as a method for PFMT.43

Mechanical Devices

Vaginal support prostheses have been in use for a long time. Although primarily used for pelvic organ prolapse, there has been interest in developing devices specifically for SUI. Pessaries, which work by providing mechanical support for the urethra, have been used for the treatment of SUI. Some potential advantages of these vaginal support devices are that they can potentially be applicable to the majority of the incontinent population, they have mild side effects, and they don’t require any specific testing (eg, urodynamic testing). Conversely, these devices do not definitively treat the problem, and if the problem worsens, the patient’s health may preclude any surgical intervention. Furthermore, these devices do not correct intrinsic sphincter deficiency, and may not help patients with hypermobility.

A recent Cochrane review looked at seven trials involving 787 women.44 Three small trials comparing mechanical devices (intravaginal such as pessary, sponge, or tampon-like device) with no treatment suggested that use of a mechanical device might be superior to no treatment; however, results were inconclusive. Five trials compared one mechanical device with another, but data were inconclusive as well, given the different outcome measures in each trial. This review ultimately concluded that there was little evidence from the controlled trials from which to judge whether the use of mechanical devices is superior to no treatment. Furthermore, there was insufficient evidence to support one device over another, and little evidence to compare mechanical devices with other forms of treatment.44

Urethral plugs passively occlude and/or coapt the urethra, and must be removed for voiding. Overall results were generally favorable from the original studies by Staskin and associates.45 Although urethral inserts are potentially applicable to almost all women with pure SUI, the fact that these devices must be removed and reinserted with each void is not attractive to most women. The highest patient acceptance seems to be among those with very predictable, episodic SUI, such as during sports or dancing. Many of these patients believe that their problem is too mild to undergo a surgical procedure but are happy to have this minimally invasive alternative.45

Electrical Stimulation

Although PFMT remains a better choice as first-line conservative therapy, another treatment option for UI in women is the use of intravaginal pelvic floor electrostimulation devices. These devices are also known for their low side-effect profile, which includes only burning or irritation at very high intensities. The mechanism of action for this modality relies on the electrical stimulation to induce hypertrophy of skeletal pelvic floor muscles via reflex contractions, while activating the detrusor inhibitory reflex arc.46,47 Prior studies have reported variable success with pelvic floor electrical stimulation; some studies did show improvement in UI whereas others found equivocal findings when compared with sham groups. Prior studies have helped determine the optimal stimulation parameters for electrical stimulation, which include a stimulation frequency of 50 Hz, alternating or biphasic current, intermittent stimulation, and optimal stimulation intensity to allow for stimulation without pain.46,47

In a recent study by Chêne and colleagues,46 359 women with UI were indentified; of these women, 207 patients were identified with pure SUI. After treatment with pelvic floor muscle stimulation, the objective cure rate was found to be 65.7% in patients with pure SUI; failure rates for the group with SUI were found to be 19.8%. Measurements of levator ani muscle tones were also improved in these patients. Incontinence scores were performed for stress, urgency, and frequency, and only the SUI group had statistically significant improvement. Quality-of-life studies for all incontinence groups were improved after electrical stimulation in all groups (stress, urgency, and frequency). The overall patient satisfaction rate for this modality was found to be 83.6%, due to patients reporting satisfaction with ease, freedom, and rapidity of use, in addition to discretion (Table 3).46

Conclusions

UI is a pervasive and increasing problem that can affect all age groups and can have a severe impact on our healthcare system and a patient’s quality of life. The armamentarium of current therapies for incontinence ranges from conservative/behavioral treatments to medical therapy to invasive surgical options. It is imperative that the specialist be able to navigate through all available options in the care of patients with incontinence. Although further research is required in the area of conservative therapies, nonsurgical treatments are effective and may be preferred by many patients. ![]()

References

- Minassian VA, Devore E, Hagan K, Grodstein F. Severity of urinary incontinence and effect on quality of life in women by incontinence type. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:1083-1090.

- Botlero R, Urquhart DM, Davis SR, Bell RJ. Prevalence and incidence of urinary incontinence in women: review of the literature and investigation of methodological issues. Int J Urol. 2008;15:230-234.

- Herzog AR, Fultz NH. Prevalence and incidence of urinary incontinence in community-dwelling populations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:273-281.

- Anger JT, Saigal CS, Litwin MS; Urologic Diseases of America Project. The prevalence of urinary incontinence among community dwelling adult women: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2006;175:601-604.

- Hu TW, Wagner TH, Bentkover JD, et al. Costs of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in the United States: a comparative study. Urology. 2004;63:461-465.

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al; Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61:37-49.

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:4-20.

- Urinary Incontinence Guideline Panel. Urinary Incontinence in Adults: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1992.

- Lucas MG, Bosch RJ, Burkhard FC, et al; European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on assessment and nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2012;62:1130-1142.

- Palmer MH. Use of health behavior change theories to guide urinary incontinence research. Nurs Res. 2004;53(6 suppl):S49-S55.

- Ostaszkiewicz J, Johnston L, Roe B. Timed voiding for the management of urinary incontinence in adults. T Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD002802.

- Hay-Smith J, Berghmans B, Burgio K, et al. Adult conservative management. In: Abrams P, Cardozo I, Khoury S, Wein A, eds., Incontinence. 4th ed. Plymouth, UK: Health Publications Ltd; 2009.

- Wallace SA, Roe B, Williams K, Palmer M. Bladder training for urinary incontinence in adults. T Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD001308.

- Riesenhuber A, Boehm M, Posch M, Aufricht C. Diuretic potential of energy drinks. Amino Acids. 2006;31:81-83.

- Creighton SM, Stanton SL. Caffeine: does it affect your bladder? Br J Urol. 1990;66:613-614.

- Lee JG, Wein AJ, Levin RM. The effect of caffeine on the contractile response of the rabbit urinary bladder to field stimulation. Gen Pharmacol. 1993; 24:1007-1011.

- Arya LA, Myers DL, Jackson ND. Dietary caffeine intake and the risk for detrusor instability: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:85-89.

- Gleason JL, Richter HE, Redden DT, et al. Caffeine and urinary incontinence in US women. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:295-302.

- Beetz R. Mild dehydration: a risk factor of urinary tract infection? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(suppl 2): S52-S58.

- Wyman JF, Burgio KL, Newman DK. Practical aspects of lifestyle modifications and behavioural interventions in the treatment of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1177-1191.

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

- Kinnunen O. Study of constipation in a geriatric hospital, day hospital, old people’s home and at home. Aging (Milano). 1991;3:161-170.

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, et al. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388-1395.

- Charach G, Greenstein A, Rabinovich P, et al. Alleviating constipation in the elderly improves lower urinary tract symptoms. Gerontology. 2001;47:72-76.

- Richter HE, Creasman JM, Myers DL, et al; Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise (PRIDE) Research Group. Urodynamic characterization of obese women with urinary incontinence undergoing a weight loss program: the Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise (PRIDE) trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1653-1658.

- Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. BMI, waist circumference, and incident urinary incontinence in older women. Obesity. 2008;16:881-886.

- Townsend MK, Danforth KN, Rosner B, et al. Body mass index, weight gain, and incident urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):346-353.

- Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, et al; PRIDE Investigators. Weight loss to treat urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:481-490.

- Danforth KN, Shah AD, Townsend MK, et al. Physical activity and urinary incontinence among healthy, older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:721-727.

- Shah SM, Gaunay GS. Treatment options for intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:638-651.

- Townsend MK, Danforth KN, Rosner B, et al. Physical activity and incident urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. J Urol. 2008;179:1012-1016.

- Bump RC, McClish DK. Cigarette smoking and urinary incontinence in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1213-1218.

- Dallosso HM, McGrother CW, Matthews RJ, Donaldson MM; Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Group. The association of diet and other lifestyle factors with overactive bladder and stress incontinence: a longitudinal study in women. BJU Int. 2003;92:69-77.

- Khan ZE, Rizvi J. Non-surgical management of urinary stress incontinence. Rev Gynaecol Pract. 2005;5:237-242.

- Lightner DJ, Itano NM. Treatment options for women with stress urinary incontinence. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:1149-1156.

- Moore K, Dumouline C, et al. Adult conservative management. In: Abrams P, Cardozo I, Khoury S, Wein A, eds. Incontinence: 5th International Consultation on Incontinence. Paris: ICUD-EAU; 2013.

- Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD005654.

- Mørkved S, Bø K, Fjørtoft T. Effect of adding biofeedback to pelvic floor muscle training to treat urodynamic stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:730-739.

- Herderschee R, Hay-Smith EC, Herbison GP, et al. Feedback or biofeedback to augment pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women: shortened version of a Cochrane systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32:325-329.

- Thor KB, Donatucci C. Central nervous system control of the lower urinary tract: new pharmacological approaches to stress urinary incontinence in women. J Urol. 2004;172:27-33.

- Ghoniem GM, Van Leeuwen JS, Elser DM, et al; Duloxetine/Pelvic Floor Muscle Training Clinical Trial Group. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine alone, pelvic floor muscle training alone, combined treatment and no active treatment in women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2005;173:1647-1653.

- Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1124-1133.

- Herbison GP, Dean N. Weighted vaginal cones for urinary incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD002114.

- Lipp A, Shaw C, Glavind K. Mechanical devices for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD001756.

- Staskin D, Bavendam T, Miller J, et al. Effectiveness of a urinary control insert in the management of stress urinary incontinence: early results of a multicenter study. Urology. 1996;47:629-636.

- Chêne G, Mansoor A, Jacquetin B, et al. Female urinary incontinence and intravaginal electrical stimulation: an observational prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170:275-280.

- Brubaker L, Benson JT, Bent A, et al. Transvaginal electrical stimulation for female urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:536-540.

- Fantl JA, Wyman JF, McClish DK, et al. Efficacy of bladder training in older women with urinary incontinence. JAMA. 1991;265:609-613.

- Lagro-Janssen AL, Debruyne FM, Smits AJ, van Weel C. The effects of treatment of urinary incontinence in general practice. Fam Pract. 1992;9:284-289.

- Yoon HS, Song HH, Ro YJ. A comparison of effectiveness of bladder training and pelvic muscle exercise on female urinary incontinence. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40:45-50.

- Colombo M, Zanetta G, Scalambrino S, Milani R. Oxybutynin and bladder training in the management of female urinary urge incontinence: a randomized study. Int Urogynecol J. 1995;6:63-67.

- Herbison GP, Lauti M, Hay-Smith J, Wilson D. Three month results from the urgent pilot study: a randomised controlled trial comparing drug therapy, bladder retraining and their combination in patients with urge urinary incontinence. In: Proceedings of the International Continence Society and the International UroGynecological Association 34th Annual Meeting; August 24-27, 2004; Paris, France. Abstract 174.

- Jarvis GJ. A controlled trial of bladder drill and drug therapy in the management of detrusor instability. Br J Urol. 1981;53:565-566.

- Wyman JF, Fantl JA, McClish DK, Bump RC. Comparative efficacy of behavioral interventions in the management of female urinary incontinence. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:999-1007.

- Bø K, Talseth T, Holme I. Single blind, randomised controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no treatment in management of genuine stress incontinence in women. BMJ. 1999;318:487-493.

- Castro RA, Arruda RM, Zanetti MR, et al. Single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no active treatment in the management of stress urinary incontinence. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2008;63:465-472.

- Lagro-Janssen TL, Debruyne FM, Smits AJ, van Weel C. Controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises in the treatment of urinary stress incontinence in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1991;41:445-449.

- Bidmead J, Mantle J, Cardozo L, et al. Home electrical stimulation in addition to conventional pelvic floor exercises: a useful adjunct or expensive distraction? Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:356-373.

- Burns PA, Pranikoff K, Nochajski TH, et al. A comparison of effectiveness of biofeedback and pelvic muscle exercise treatment of stress incontinence in older community-dwelling women. J Gerontol. 1993;48:M167-M174.

- Henalla SM, Hutchins CJ, Robinson P, MacVicar J. Non-operative methods in the treatment of female genuine stress incontinence of urine. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;9:222-225.

- Aksac B, Aki S, Karan A, et al. Biofeedback and pelvic floor exercises for the rehabilitation of urinary stress incontinence. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2003;56:23-27.

- Henalla SM, Millar D, Wallace KJ. Surgical versus conservative management for post-menopausal genuine stress incontinence of urine [abstract 87]. Neurourol Urodyn. 1990;9:436-437.

- Kim H, Suzuki T, Yoshida Y, Yoshida H. Effectiveness of multidimensional exercises for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in elderly community-dwelling Japanese women: A randomized, controlled, crossover trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1932-1939.

- Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. A pelvic muscle precontraction can reduce cough-related urine loss in selected women with mild SUI. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:870-874.

- Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1995-2000.