Treatment of Colonic Injury During Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Hakan Öztürk, MD

Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Sifa University, Izmir, Turkey

Colonic injury during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) persists despite the advances in technical equipment and interventional radiology techniques. According to the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications, colonic injury is regarded as a stage IVa complication. Currently, the rate of colonic injury ranges between 0.3% and 0.5%, with an unremarkable difference in incidence between supine and prone PCNL procedures. Colon injury is the most significant complication of PCNL. Colonic injury can result in more complicated open exploration of the abdomen, involving colostomy construction. The necessity of a second operation for the closure of the colostomy causes financial and emotional burden on the patients, patients’ relatives, and surgeons. Currently, the majority of colonic injuries occurring during PCNL are retroperitoneal. The primary treatment option is a conservative approach. It must be kept in mind that the time of diagnosis is as important as the diagnosis itself in colonic injury. Surgeons performing PCNL are advised to be conservative when considering exploratory laparotomy and colostomy construction during treatment of colonic injury. We present the case of a 49-year-old woman who underwent left prone PCNL that resulted in retroperitoneal colonic injury, along with a review of the current literature.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(3):194-201 doi: 10.3909/riu0641]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Treatment of Colonic Injury During Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Hakan Öztürk, MD

Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Sifa University, Izmir, Turkey

Colonic injury during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) persists despite the advances in technical equipment and interventional radiology techniques. According to the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications, colonic injury is regarded as a stage IVa complication. Currently, the rate of colonic injury ranges between 0.3% and 0.5%, with an unremarkable difference in incidence between supine and prone PCNL procedures. Colon injury is the most significant complication of PCNL. Colonic injury can result in more complicated open exploration of the abdomen, involving colostomy construction. The necessity of a second operation for the closure of the colostomy causes financial and emotional burden on the patients, patients’ relatives, and surgeons. Currently, the majority of colonic injuries occurring during PCNL are retroperitoneal. The primary treatment option is a conservative approach. It must be kept in mind that the time of diagnosis is as important as the diagnosis itself in colonic injury. Surgeons performing PCNL are advised to be conservative when considering exploratory laparotomy and colostomy construction during treatment of colonic injury. We present the case of a 49-year-old woman who underwent left prone PCNL that resulted in retroperitoneal colonic injury, along with a review of the current literature.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(3):194-201 doi: 10.3909/riu0641]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Treatment of Colonic Injury During Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

Hakan Öztürk, MD

Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Sifa University, Izmir, Turkey

Colonic injury during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) persists despite the advances in technical equipment and interventional radiology techniques. According to the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications, colonic injury is regarded as a stage IVa complication. Currently, the rate of colonic injury ranges between 0.3% and 0.5%, with an unremarkable difference in incidence between supine and prone PCNL procedures. Colon injury is the most significant complication of PCNL. Colonic injury can result in more complicated open exploration of the abdomen, involving colostomy construction. The necessity of a second operation for the closure of the colostomy causes financial and emotional burden on the patients, patients’ relatives, and surgeons. Currently, the majority of colonic injuries occurring during PCNL are retroperitoneal. The primary treatment option is a conservative approach. It must be kept in mind that the time of diagnosis is as important as the diagnosis itself in colonic injury. Surgeons performing PCNL are advised to be conservative when considering exploratory laparotomy and colostomy construction during treatment of colonic injury. We present the case of a 49-year-old woman who underwent left prone PCNL that resulted in retroperitoneal colonic injury, along with a review of the current literature.

[Rev Urol. 2015;17(3):194-201 doi: 10.3909/riu0641]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Colonic injury • Percutaneous nephrolithotomy • Clavien • Complication • Prevention • Urolithiasis • Management

Key words

Colonic injury • Percutaneous nephrolithotomy • Clavien • Complication • Prevention • Urolithiasis • Management

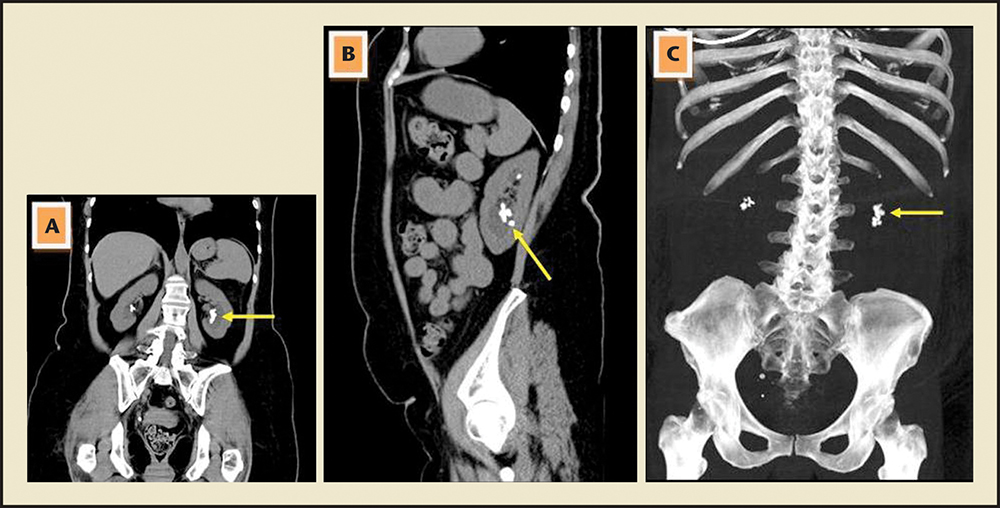

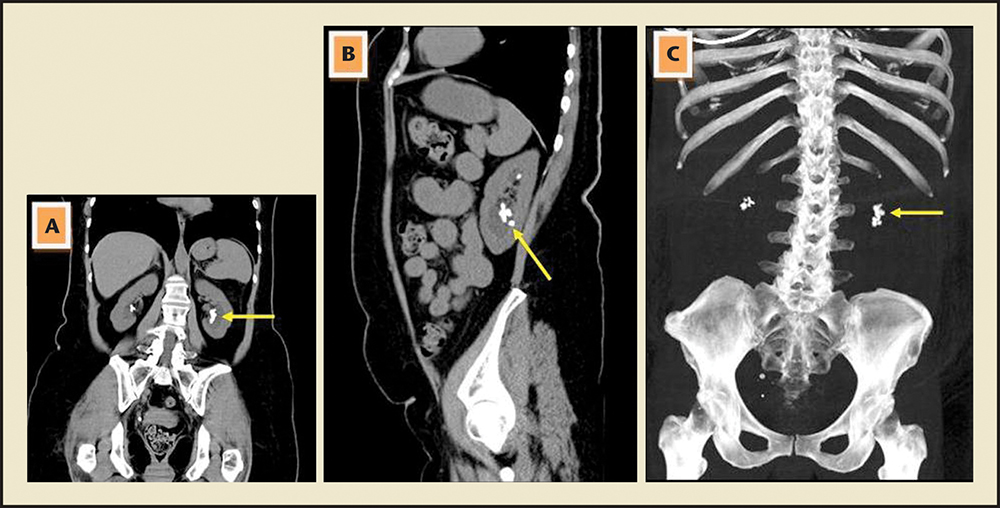

Figure 1. (A) Preoperative computed tomography (CT) image showing coronal reconstruction (arrow: left kidney stones). (B) Preoperative CT imaging showing sagittal reconstruction (arrow: left kidney stones). (C) Preoperative CT image showing digital subtraction (arrow: stones).

Figure 1. (A) Preoperative computed tomography (CT) image showing coronal reconstruction (arrow: left kidney stones). (B) Preoperative CT imaging showing sagittal reconstruction (arrow: left kidney stones). (C) Preoperative CT image showing digital subtraction (arrow: stones).

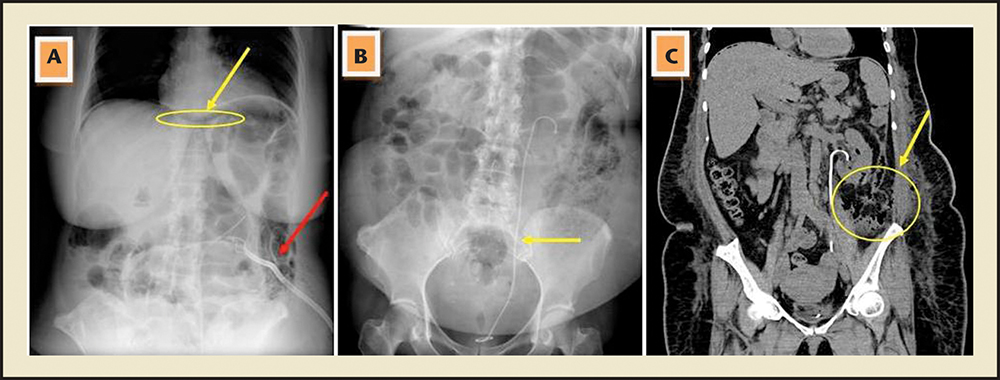

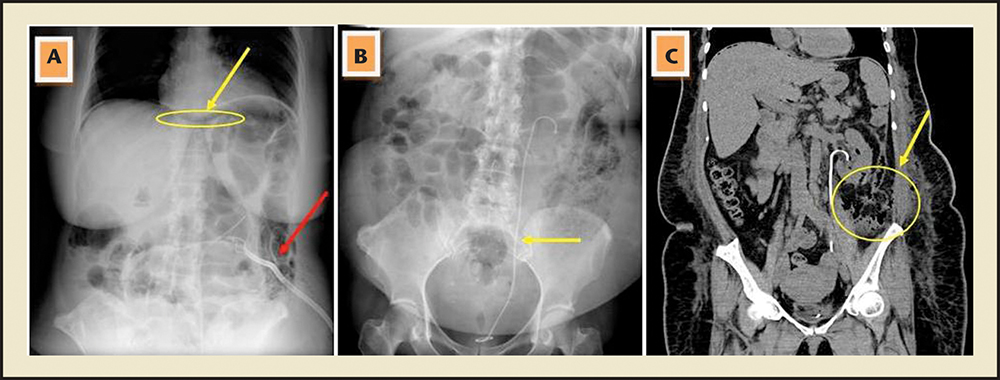

Figure 2. (A) Postoperative abdominal radiograph (yellow arrow: free air in the abdomen; red arrow: nephrostomy tube). (B) Postoperative abdominal radiograph (arrow: left double J stent). (C) Postoperative computed tomography image showing coronal reconstruction (arrow: retroperitoneal inflammation).

Figure 2. (A) Postoperative abdominal radiograph (yellow arrow: free air in the abdomen; red arrow: nephrostomy tube). (B) Postoperative abdominal radiograph (arrow: left double J stent). (C) Postoperative computed tomography image showing coronal reconstruction (arrow: retroperitoneal inflammation).

The colonic injury indicated recovery on day 10 without development of nephrocolic or colocutaneous fistula.

Colon injury primarily occurs during left-sided PCNL. A puncture placed too laterally may injure the colon.

Prompt recognition of a colonic perforation is critical to limiting serious infectious sequelae.

Although conservative methods proved effective in the majority of colon injuries, hemicolectomy may be required in large colon injuries.

Supine PCNL can be preferred due to disadvantages related to the anesthesia, neurosurgical, and orthopedic pathologies, circulation problems in obese patients, and hemodynamic and ventilation problems.

In case of intraperitoneal colonic perforation, peritonitis, or sepsis, or in the failure of conservative management, open surgical exploration should be performed…

Main Points

• Colonic injury during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) persists despite the advances in technical equipment and interventional radiology techniques. Colon injury is the most significant complication of PCNL, and rates of colonic injury range between 0.3% and 0.5%, with an unremarkable difference in incidence between the supine and prone PCNL procedures. Colon injury is of great significance, due to its diagnostic challenges, as well as severe and fatal complications.

• Factors such as previous intestinal bypass surgery, female sex, old age, low body weight, horseshoe kidney, and previous renal surgery increase the risk of colonic injury during PCNL.

• Prompt recognition of a colonic perforation is critical to limiting serious infectious sequelae. Colon perforation should be suspected if the patient develops unexplained fever or has intraoperative or immediate postoperative diarrhea or hematochezia, signs of peritonitis, or passage of gas or feces through the nephrostomy tract.

• Although conservative methods proved effective in the majority of colon injuries, hemicolectomy may be required in large colon injuries. Conservative therapies include total parenteral nutrition, terminating oral intake, leaving the endopyelotomy catheter in place for a long time, repositioning the nephrostomy catheter within the colon lumen, and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

• After the diagnosis of colon injury is established, a permanent J stent must be inserted, and, under fluoroscopic observation, the nephrostomy tube must be repositioned and left in the colon. In addition, a Foley catheter must be inserted to relieve the pressure in the urinary system.

• Of critical importance in colon injury is the timing of the diagnosis. The success rate of conservative therapy is 86% if the diagnosis is made perioperatively, or postoperatively before the removal of the nephrostomy tube; however, the rate of success decreases by 50% if the diagnosis is delayed and the nephrostomy tube is removed before recognizing colon injury.

Main Points

• Colonic injury during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) persists despite the advances in technical equipment and interventional radiology techniques. Colon injury is the most significant complication of PCNL, and rates of colonic injury range between 0.3% and 0.5%, with an unremarkable difference in incidence between the supine and prone PCNL procedures. Colon injury is of great significance, due to its diagnostic challenges, as well as severe and fatal complications.

• Factors such as previous intestinal bypass surgery, female sex, old age, low body weight, horseshoe kidney, and previous renal surgery increase the risk of colonic injury during PCNL.

• Prompt recognition of a colonic perforation is critical to limiting serious infectious sequelae. Colon perforation should be suspected if the patient develops unexplained fever or has intraoperative or immediate postoperative diarrhea or hematochezia, signs of peritonitis, or passage of gas or feces through the nephrostomy tract.

• Although conservative methods proved effective in the majority of colon injuries, hemicolectomy may be required in large colon injuries. Conservative therapies include total parenteral nutrition, terminating oral intake, leaving the endopyelotomy catheter in place for a long time, repositioning the nephrostomy catheter within the colon lumen, and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

• After the diagnosis of colon injury is established, a permanent J stent must be inserted, and, under fluoroscopic observation, the nephrostomy tube must be repositioned and left in the colon. In addition, a Foley catheter must be inserted to relieve the pressure in the urinary system.

• Of critical importance in colon injury is the timing of the diagnosis. The success rate of conservative therapy is 86% if the diagnosis is made perioperatively, or postoperatively before the removal of the nephrostomy tube; however, the rate of success decreases by 50% if the diagnosis is delayed and the nephrostomy tube is removed before recognizing colon injury.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is a standard, safe, and effective method used in the management of large kidney stones. PCNL was first described by Fernström and Johansson in 1976.1 Currently, PCNL offers a 78% to 95% success rate in the treatment of kidney stones. However, the rate of major and minor complications related to the procedure is as high as 83%.2 The major complication rate for PCNL varies between 1.1% and 7%,3 despite improvements in endourologic equipment and the development of new treatment modalities, such as mini-micro PCNL, supine PCNL, and laparoscopically assisted PCNL. A wide range of complications can arise from PCNL, ranging from those requiring simple medical therapies and follow-up to more severe conditions resulting in death, and have been categorized according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system. The most common complication is hemorrhage, accounting for 1% to 12% of cases. However, the rate of hemorrhage requiring blood transfusion is less than 2.5% in the latest series reported in the literature,4 and the rate of grade V mortality is less than 0.1%. Colon injury during PCNL is classified as a grade IVa complication, and rarely occurs (in only 0.2%-0.8% of cases). However, colon injury is of great significance, due to its diagnostic challenges, as well as severe and fatal complications.2

Case Report

Clinical Features

A 49-year-old woman presented with left flank pain. Physical examination revealed tenderness on the left costovertebral angle. Biochemical analyses included the following values: glucose, 162 mg/ dL; creatinine, 0.7 mg/dL; urea, 33 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma glutamyl transferase levels, all within normal range; leukocytes, 6.54 × 103/μL; hemoglobin, 13.6 g/dL; sodium, 135 mmol/L; potassium, 4.2 mmol/L; serum chloride, 101 mEq/L; and calcium, 8.7 mg/dL. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for diabetes and she was using oral antidiabetic agents. The patient was a nonsmoker. Body mass index was 38.25. Computed tomography (CT) scans obtained before the operation revealed 28-mm urinary stones located in the left renal pelvis and associated left hydronephrosis. The colon was not in the retrorenal or lateral position. The patient was diagnosed with colon injury upon observation of colonic content passing from the nephrostomy tube at postoperative day 3 after standard PCNL procedure. Perioperative nephrostogram results were normal. The patient did not have nausea, vomiting, or sepsis, and bowel sounds were normal. The passage of gas and stool was normal, and there was no sign of acute abdomen or peritonitis.

Radiologic Features

The preoperative radiologic evaluation of the patient did not reveal any risk factors for colonic injury. Multiple kidney stones were detected in the left renal pelvis and lower pole of the kidney (Figure 1). The postoperative abdominal radiographs showed subdiaphragmatic free air in the abdomen. Postoperative CT revealed normal intra-abdominal findings, and there was inflammation in the retroperitoneal area (Figure 2).

Treatments

The left kidney and colon were separated with the insertion of a J stent (Figure 2A). The Foley catheter was left in place, which allowed recovery of the medial wall of the colon; oral intake was terminated to rest the bowel. A nephrostography was performed to replace the nephrostomy tube in the pericolic area under scopic examination. The patient was placed on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and dual broad-spectrum antibiotherapy (ceftriaxone and ornidazole). She did not have a fever during this period. Postoperative C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 47 mg/dL at 24 hours; CRP levels rapidly decreased to 1 mg/dL at the end of the treatment. The colonic content was reduced from 300 mL/d to 50 mL/d in 1 week. The nephrostomy tube inserted to the pericolic area was completely removed with the anticipation of total recovery of the lateral colonic wall. Oral intake was restarted after 1 week and the Foley catheter was removed. The colonic injury indicated recovery on day 10 without development of nephrocolic or colocutaneous fistula. The J stent was extirpated after 3 weeks. Retroperitoneal colonic injury was therefore successfully treated with nonoperative conservative methods.

Discussion

Colonic perforation is a rare complication of percutaneous kidney surgery, and it is reported in less than 1% of cases. According to recent data in the literature, the rate may be less than 0.5%. Colon injury primarily occurs during left-sided PCNL. A puncture placed too laterally may injure the colon. The position of the colon is usually anterior or anterolateral to the lateral renal border; therefore, risk of colon injury usually exists only with a very lateral puncture (lateral to the posterior axillary line).5 Hadar and Gadoth6 and Sherman and colleagues7 reported retrorenal position of the colon in 0.6% of the general population. Hopper and colleagues8 examined 500 CT scans of the abdomen and reported that the overall prevalence of the retrorenal colon was 1.9% in the supine position.

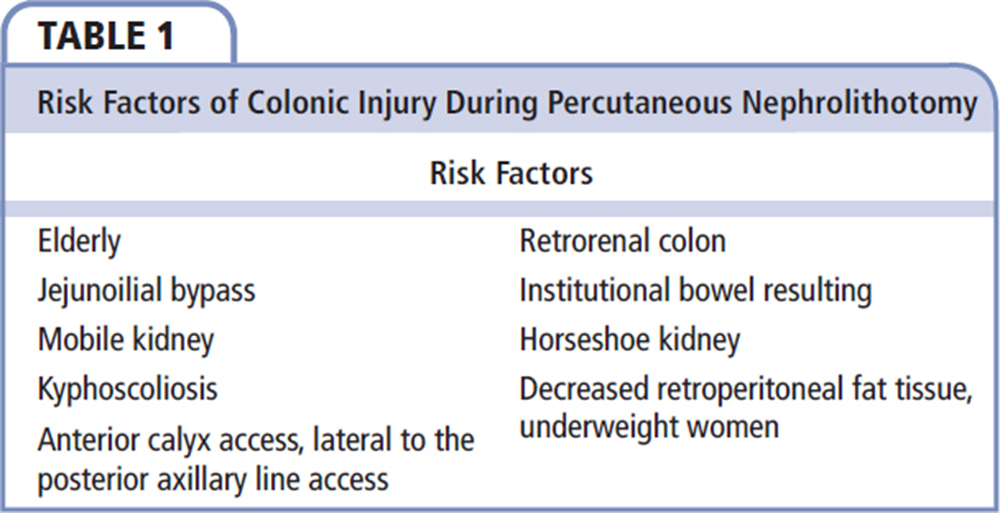

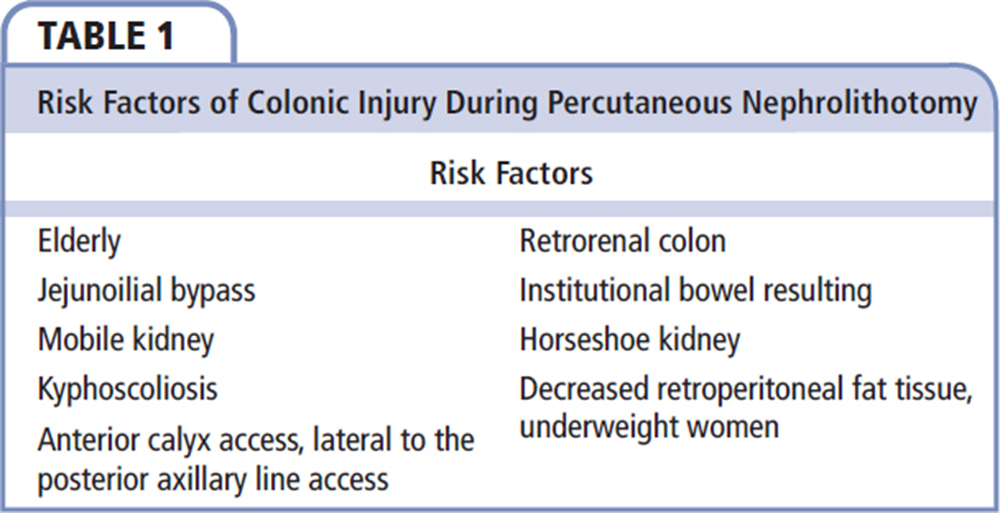

Elderly patients with chronic constipation or patients with other causes of colonic distention, patients who previously underwent major abdominal surgery (jejunoileal bypass, partial jejunoileal bypass), or those with neurologic impairment and institutional bowel resulting in an enlarged colon exhibit displacement of the colon posterior to the kidney and have increased risk of colon perforation. Other factors that increase the risk of colon injury include female sex, patients with very little retroperitoneal fat, patients with mobile kidneys, anterior calyceal puncture, previous extensive renal surgery, horseshoe kidney and other forms of renal fusion or ectopia, and patients with kyphoscoliosis.5 Risk factors of colonic injury are summarized in Table 1.

Prompt recognition of a colonic perforation is critical to limiting serious infectious sequelae. Colon perforation should be suspected if the patient develops unexplained fever or has intraoperative or immediate postoperative diarrhea or hematochezia, signs of peritonitis, or passage of gas or feces through the nephrostomy tract.9 Although fever and sepsis are important parameters for colonic injury, it should be noted that 0.6% to 1.5% of the patients undergoing PCNL operation develop sepsis.10

Colon perforation should be considered the source of sepsis in patients who remain unresponsive to the administered therapy due to fever, and obtaining CT scans is recommended at this stage. However, the best diagnostic tool used to detect perforation of the colon by the nephrostomy tube is abdominal CT. Unrecognized colonic injury can result in abscess formation, nephrocolic or colocutaneous fistulae, peritonitis, or sepsis.11 According to a report in the literature in 1985, LeRoy and associates12 successfully treated two cases of colon injury that occurred after PCNL using conservative methods while avoiding colostomy. In a series of five patients with extraperitoneal colon injury reported by Gerspach and associates,11 all patients were treated with conservative methods.

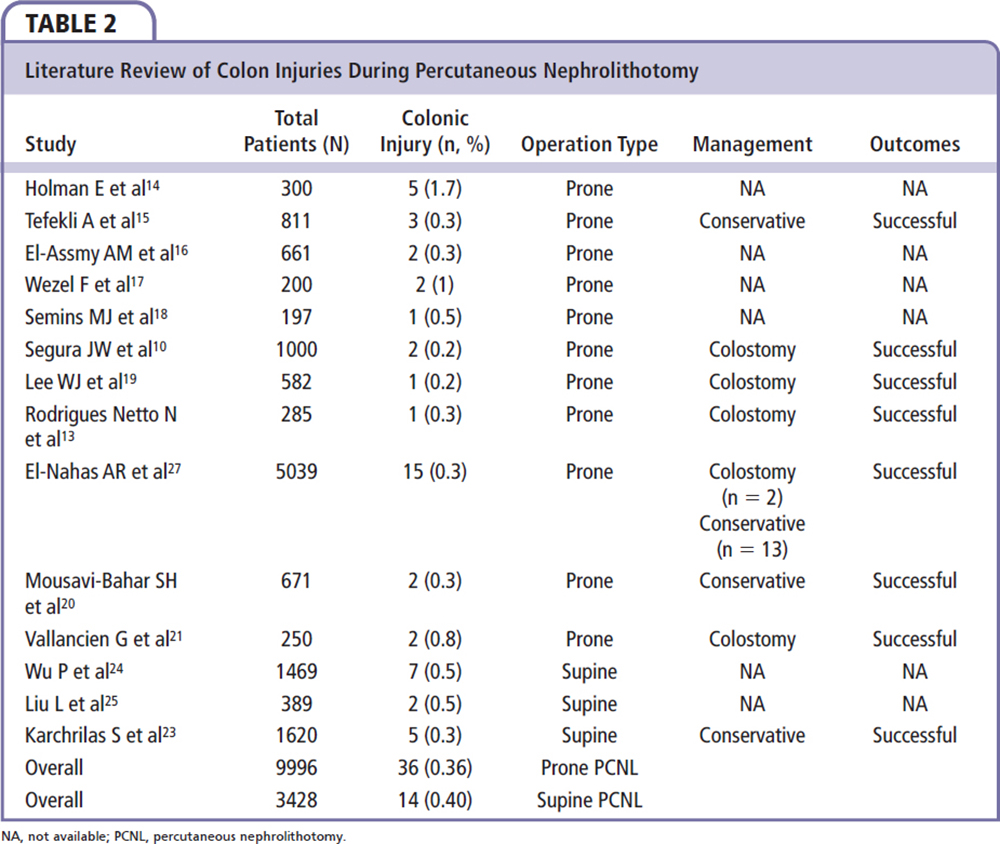

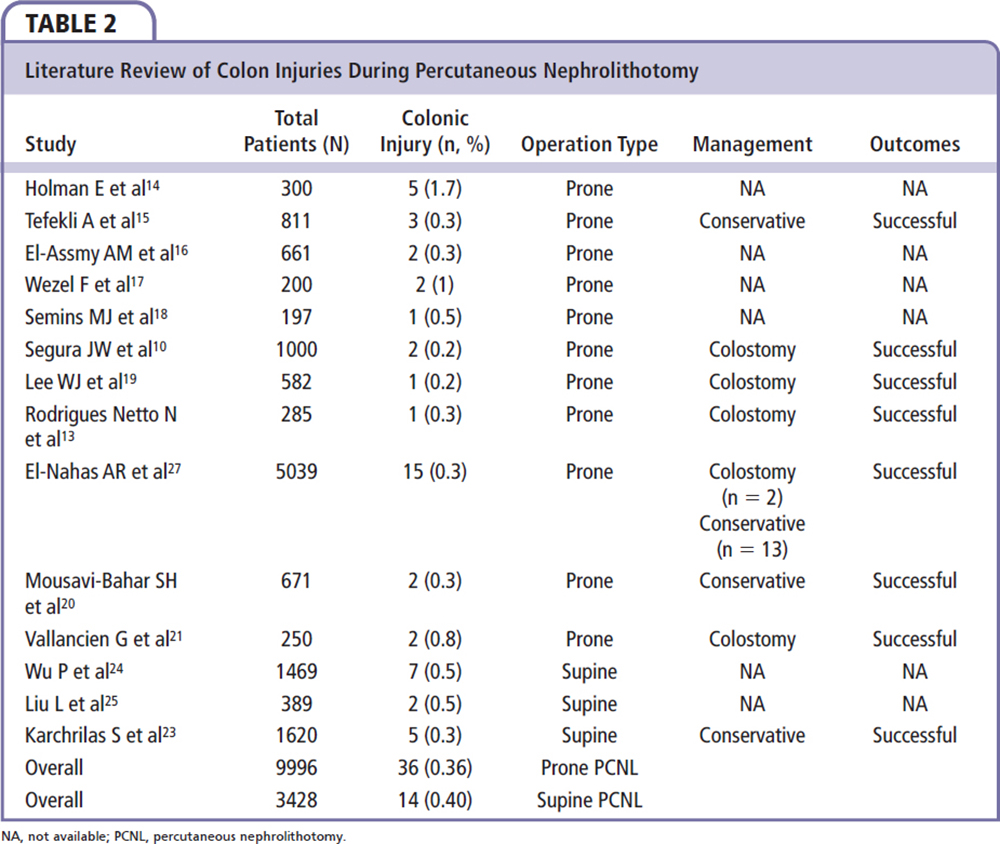

In their study, Rodrigues Netto and coworkers13 detected one colon injury in 285 patients; the patient was later treated with colostomy. In a study by Holman and associates,14 no colon injury occurred in 150 patients who underwent bilateral simultaneous PCNL procedure; however, they did report five cases of colon injury in another series of 300 patients. In the study by Tefekli and colleagues,15 all cases of colon injury (n = 3) were treated with conservative methods. El-Assmy and colleagues16 studied 661 patients and reported colon injury in only two. In the same series of patients, the rate of colon injury was reported to increase by 50% if the procedure was performed by a radiologist. This study suggests that access should be performed by a urologist during PCNL procedure. The prevalence of colon injury in the studies by Wezel and associates17 and Semins and associates18 was reported to be 0.5% and 1%, respectively. In the study by Segura and coworkers,10 a total of three patients with colon injury were treated with colostomy. In a study by Lee and coworkers,19 the rate of colon injury (n = 582) was very low (0.2%), and this case required colostomy. In the study by Mousavi-Bahar and colleagues,20 two cases of colon injury were treated with conservative methods. In a series of 250 patients reported by Vallancien and associates,21 two cases of colon injury were treated with colostomy. In one of these patients, colon injury was suspected only as a result of rectal bleeding. In this series, colostomy was inevitable in one patient due to the presence of intraperitoneal injury; however, the other patient had retroperitoneal colon injury. This case was also treated with colostomy. This patient might have been treated with colostomy due to limited availability of PCNL equipment and diagnostic tools in 1985, and lack of consensus in the literature regarding conservative treatment of colon injury. In the study by Ba’adani and coworkers,22 hemicolectomy was required in a patient with delayed diagnosis of fecal fistula that developed after the PCNL procedure.

Although conservative methods proved effective in the majority of colon injuries, hemicolectomy may be required in large colon injuries. Kachrilas and colleagues23 reported five colon injuries in a series of 1620 patients. The most striking feature of this series is that all colon injuries occurred in the supine-position PCNL procedure. The five patients with colon injuries in the series underwent other procedures in addition to PCNL; two patients underwent supine PCNL plus antegrade endopyelotomy due to right kidney stone and right ureteropelvic junction stenosis. Fever that occurred in postoperative days 1 and 3 and discharge of colonic content from the Malecot catheter were the common clinical features in these patients; both patients also had ascending colon injury. The patients were treated with conservative methods that included TPN, terminating oral intake, leaving the endopyelotomy catheter in place for a long time, repositioning of the nephrostomy catheter within the colon lumen, and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics (ampicillin 1 metronidazole 1 gentamicin or imipenem 1 vancomycin 1 metronidazole). The nephrostomy tube was withdrawn after 10 to 14 days, and the endopyelotomy catheter was withdrawn after 6 weeks. Abdominal CT scans obtained at 3 months did not reveal any pathology between the kidney and colon. The other patient underwent left supine PCNL and simultaneous flexible ureterorenoscopy due to staghorn kidney stone and developed a descending colon injury. The patient did not have intra-abdominal fluid collection and was treated with conservative methods, including the repositioning of the nephrostomy tube in the colon and the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. The other patient sustained injury to the colonic diverticula. Diverticular colon disease may pose a risk for intervention to the lower pole of the kidney. This case was also successfully treated with conservative methods.23

As an alternative to supine PCNL, standard prone PCNL was not shown to increase complication rates. Supine PCNL can be preferred due to disadvantages related to the anesthesia, neurosurgical, and orthopedic pathologies, circulation problems in obese patients, and hemodynamic and ventilation problems. The most important and debated point is the concern of a higher rate of colon injuries with the supine PCNL procedure; however, supine PCNL does not increase the rate of complications compared with standard PCNL. In meta-analyses by Wu and colleagues24 and Liu and colleagues,25 the complication rates were not different between supine PCNL and standard PCNL; supine PCNL was found to be as effective and safe as prone PCNL. The rate of colon injury was 0.5%—similar to that reported in the literature. After the diagnosis of colonic perforation is made, the first step of treatment involves the separation of the nephrocolic communication.26 A permanent J stent must be inserted, and, under fluoroscopic observation, the nephrostomy tube must be repositioned and left in the colon. In addition, a Foley catheter must be inserted to relieve the pressure in the urinary system. The patient must be administered broad-spectrum antibiotics (covering anaerobic colon bacteria) or triple antibiotic therapy. The patient should be administered a low-residue diet or TPN to stop oral intake for bowel rest. Intrarectal and intracolonic pressure should be decreased by anal dilation. This allows the recovery of the renal collecting system and closure of the medial colonic wall. If colostogram or retrograde pyelogram performed after 5 to 7 days does not exhibit extravasation or communication between the colon and collecting system, the Foley catheter should be removed and the colostomy tube withdrawn, but left in place as a drainage site other than the colon. The tube should be completely removed after 2 to 3 days (7-10 d in total) if the lateral wall of the colon is assumed to be closed and if there is no sign of persistent nephrocolic fistula. In case of intraperitoneal colonic perforation, peritonitis, or sepsis, or in the failure of conservative management, open surgical exploration should be performed, and a colostomy is usually necessary.5,26 It is recommended that the tube be removed after complete healing of the colon is confirmed by barium enema on day 8, or complete separation is confirmed on J stent retrograde pyelography 4 to 6 weeks later. A temporary colostomy for 3 months is essential in patients with colocutaneous fistula, despite the use of conservative therapy. Most important in colon injury is the timing of the diagnosis. The success rate of conservative therapy is 86% (13/15) if the diagnosis is made perioperatively, or postoperatively before the removal of the nephrostomy tube. However, the rate of success decreases by half down to 40% if the diagnosis is delayed and the nephrostomy tube is removed before recognizing colon injury. Four of 10 patients will require colostomy26; therefore, preoperative risk assessment should include an evaluation of the projection of access via CT scan, spatial relation between the colon and the kidney, and the presence of retrorenal colon. In the case of any complication, the operation should be terminated by performing nephrosonography, the nephrostomy tube should be repositioned, and supportive therapy should be initiated.

In their study, El Nahas and associates27 detected colon injury in 15 of 5039 patients (0.29%). Colonic perforation complicated lower calyceal puncture in 12 procedures (80%), and complicated upper caliceal punctures in those with horseshoe kidneys or chronic colonic distension. Of these 15 patients, 5 were diagnosed perioperatively and 10 were diagnosed postoperatively. Of the colon injuries, 66% occurred during left-sided PCNL procedure and 34% occurred in right-sided PCNL procedure. In right-sided injuries, all patients had horseshoe kidney or previous history of renal surgery. The most important independent risk factors observed in this study were advanced patient age and the presence of horseshoe kidney. Of the patients, 13 were treated with conservative methods and 2 patients required colostomy. It must be noted that all injuries were retroperitoneal. Early diagnosis and proper treatment represent the key to minimizing patient morbidity and avoiding serious complications.27

Some authors, however, suggest that repositioning of the nephrostomy tube into the colon is sufficient in colon injury and internal urinary drainage has no benefit. Nouira and coworkers28 demonstrated conservative treatment of colon injury without performing internal drainage.

In their study, Miranda and colleagues29 inserted a flexible fibrin glue applicator into the nephrostomy tract and injected approximately 5 mL of fibrin glue to treat colon injury. The closure of the fistula tract was then confirmed by radiologic investigation. In this study, the application of fibrin glue appears as an alternative to the supportive therapy in colon injuries. This method may decrease the number of patients that require colostomy in circumstances in which the drainage from colocutaneous fistula was decreased but not completely ceased. However, this method has some potential complications, including allergic reaction, immunologically induced coagulopathy, thromboembolic complications, and the theoretical risk of viral transmission.

Advanced age and horseshoe kidney are independent risk factors for colonic injury during PCNL. Interestingly, the presence of retrorenal colon or extremely lateral intervention is not regarded as independent risk factors. The literature concerning colon injuries during percutaneous nephrolithotomy is summarized in Table 2.

Conclusions

Some factors may increase risk of colonic injury during PCNL, such as previous intestinal bypass surgery, female sex, old age, low body weight, horseshoe kidney, and previous renal surgery. The likelihood of colonic injury is greater on the left side, with lower calyceal puncture of lateral origin. The most important etiology for this complication is retrorenal or posterolateral position of the colon. Early diagnosis and management is the best way to avoid complications from colonic perforation. A nephrostography should be obtained after tubeless and/or total tubeless PCNL, which is now performed more often. ![]()

The author reports no real or apparent conflicts of interest. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient who participated in this case. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

References

- Fernström I, Johansson B. Percutaneous pyelolithotomy. A new extraction technique. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1976;10:257-259.

- Michel MS, Trojan L, Rassweiler JJ. Complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol. 2007;51:899-906.

- Lingeman JE, Lifshitz DA, Evan AP. Surgical management of urinary lithiasis. In: Walsh PC, Retick AB, Vaughan ED Jr, Wein AJ, eds. Campbell’s Urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2002: 3361-3451.

- Soucy F, Ko R, Duvdevani M, et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for staghorn calculi: a single center’s experience over 15 years. J Endourol. 2009;23:1669-1673.

- Traxer O. Management of injury to the bowel during percutaneous stone removal. J Endourol. 2009;23:1777-1780.

- Hadar H, Gadoth N. Positional relations of colon and kidney determined by perirenal fat. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:773-776.

- Sherman JL, Hopper KD, Greene AJ, Johns TT. The retrorenal colon on computed tomography: a normal variant. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9:339-341.

- Hopper KD, Sherman JL, Williams MD, Ghaed N. The variable anteroposterior position of the retroperitoneal colon to the kidneys. Invest Radiol. 1987;22: 298-302.

- Assimos DG. Complications of stone removal. In: Smith AD, Badlani GH, Bagley DH, et al, eds. Smith’s Textbook of Endourology. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 1996: 298-308.

- Segura JW, Patterson DE, LeRoy AJ, et al. Percutaneous removal of kidney stones: review of 1,000 cases. J Urol. 1985;134:1077-1081.

- Gerspach JM, Bellman GC, Stoller ML, Fugelso P. Conservative management of colon injury following percutaneous renal surgery. Urology. 1997;49: 831-836.

- LeRoy AJ, Williams HJ Jr, Bender CE, et al. Colon perforation following percutaneous nephrostomy and renal calculus removal. Radiology. 1985;155:83-85.

- Rodrigues Netto N Jr, Lemos GC, Fiuza JL. Colon perforation following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urology. 1988;32:223-224.

- Holman E, Salah MA, Tóth C. Comparison of 150 simultaneous bilateral and 300 unilateral percutaneous nephrolithotomies. J Endourol. 2002;16:33-36.

- Tefekli A, Altunrende F, Tepeler K, et al. Tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy in selected patients: a prospective randomized comparison. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;39:57-63.

- El-Assmy AM, Shokeir AA, Mohsen T, et al. Renal access by urologist or radiologist for percutaneous nephrolithotomy—is it still an issue? J Urol. 2007;178: 916-920.

- Wezel F, Mamoulakis C, Rioja J, et al. Two contemporary series of percutaneous tract dilation for percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol. 2009;23: 1655-1661.

- Semins MJ, Bartik L, Chew BH, et al. Multicenter analysis of postoperative CT findings after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: defining complication rates. Urology. 2011;78:291-294.

- Lee WJ, Smith AD, Cubelli V, et al. Complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:177-180.

- Mousavi-Bahar SH, Mehrabi S, Moslemi MK. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy complications in 671 consecutive patients: a single-center experience. Urol J. 2011;8:271-276.

- Vallancien G, Capdeville R, Veillon B, et al. Colonic perforation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Urol. 1985;134:1185-1187.

- Ba’adani T, Al-Kata’a M, Makhlafi T. Cecal fistula after pnl ended by hemicolectomy. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:484-485.

- Kachrilas S, Papatsoris A, Bach C, et al. Colon perforation during percutaneous renal surgery: a 10-year experience in a single endourology centre. Urol Res. 2012;40:263-268.

- Wu P, Wang L, Wang K. Supine versus prone position in percutaneous nephrolithotomy for kidney calculi: a meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43:67-77.

- Liu L, Zheng S, Xu Y, Wei Q. Systematic review and meta-analysis of percutaneous nephrolithotomy for patients in the supine versus prone position. J Endourol. 2010;24:1941-1946.

- Seitz C, Desai M, Häcker A, et al. Incidence, prevention, and management of complications following percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy. Eur Urol. 2012;61: 146-158.

- El-Nahas AR, Shokeir AA, El-Assmy AM, et al. Colonic perforation during percutaneous nephrolithotomy: study of risk factors. Urology. 2006;67:937-941.

- Nouira Y, Nouira K, Kallel Y, et al. Colonic perforation complicating percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:47-48.

- Miranda EP, Ribeiro GP, Almeida DC, Scafuri AG. Percutaneous injection of fibrin glue resolves persistent nephrocutaneous fistula complicating colonic perforation after percutaneous nephrolithotripsy. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64:711-713.