Extent of Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection During Radical Cystectomy: Is Bigger Better?

Debasish Sundi, MD,1 Robert S. Svatek, MD, MSCI,2 Matthew E. Nielsen, MD, MS,3 Mark P. Schoenberg, MD,4 Trinity J. Bivalacqua, MD, PhD1

1The James Buchanan Brady Urological Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, MD; 2Department of Urology, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX; 3Department of Urology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC; 4Department of Urology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Bronx, NY

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) is a standard component of radical cystectomy (RC) for bladder cancer. The optimal anatomic PLND template remains undefined. An extended PLND template can potentially improve survival through the eradication of micrometastatic disease and improved pathologic staging. However, this benefit could be compromised by a potential increase in perioperative complications and cost. Two randomized controlled clinical trials that will clarify this question are ongoing. Many important retrospective studies have provided insights into the optimal PLND extent. Here the authors review the key evidence that informs how urologists may tailor the PLND template during RC depending on patient and tumor characteristics.

[Rev Urol. 2014;16(4):159-166 doi: 10.3909/riu0626]

© 2014 MedReviews®, LLC

Extent of Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection During Radical Cystectomy: Is Bigger Better?

Debasish Sundi, MD,1 Robert S. Svatek, MD, MSCI,2 Matthew E. Nielsen, MD, MS,3 Mark P. Schoenberg, MD,4 Trinity J. Bivalacqua, MD, PhD1

1The James Buchanan Brady Urological Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, MD; 2Department of Urology, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX; 3Department of Urology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC; 4Department of Urology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Bronx, NY

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) is a standard component of radical cystectomy (RC) for bladder cancer. The optimal anatomic PLND template remains undefined. An extended PLND template can potentially improve survival through the eradication of micrometastatic disease and improved pathologic staging. However, this benefit could be compromised by a potential increase in perioperative complications and cost. Two randomized controlled clinical trials that will clarify this question are ongoing. Many important retrospective studies have provided insights into the optimal PLND extent. Here the authors review the key evidence that informs how urologists may tailor the PLND template during RC depending on patient and tumor characteristics.

[Rev Urol. 2014;16(4):159-166 doi: 10.3909/riu0626]

© 2014 MedReviews®, LLC

Extent of Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection During Radical Cystectomy: Is Bigger Better?

Debasish Sundi, MD,1 Robert S. Svatek, MD, MSCI,2 Matthew E. Nielsen, MD, MS,3 Mark P. Schoenberg, MD,4 Trinity J. Bivalacqua, MD, PhD1

1The James Buchanan Brady Urological Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, MD; 2Department of Urology, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX; 3Department of Urology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC; 4Department of Urology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Bronx, NY

Pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) is a standard component of radical cystectomy (RC) for bladder cancer. The optimal anatomic PLND template remains undefined. An extended PLND template can potentially improve survival through the eradication of micrometastatic disease and improved pathologic staging. However, this benefit could be compromised by a potential increase in perioperative complications and cost. Two randomized controlled clinical trials that will clarify this question are ongoing. Many important retrospective studies have provided insights into the optimal PLND extent. Here the authors review the key evidence that informs how urologists may tailor the PLND template during RC depending on patient and tumor characteristics.

[Rev Urol. 2014;16(4):159-166 doi: 10.3909/riu0626]

© 2014 MedReviews®, LLC

Key words

Pelvic lymph node dissection • Radical cystectomy • Template • Micrometastatic disease

Key words

Pelvic lymph node dissection • Radical cystectomy • Template • Micrometastatic disease

Bilateral PLND is widely accepted over unilateral PLND in bladder cancer given the substantial crossover that exists for lymph node metastasis.

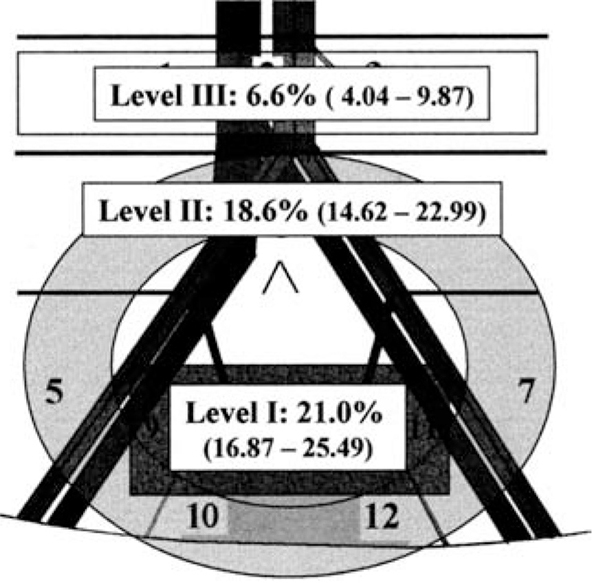

Figure 1. Anatomic pelvic lymph node dissection levels: I, II, and III. Percentages of patients with lymph node metastases at each level are shown (from a series of 290 patients who had super-extended PLND including levels I, II, and III). Adapted from Leissner J et al.13

Lymph node yields are highly variable and depend on multiple factors, limiting their utility as a standard threshold metric for the adequacy of PLND at RC.

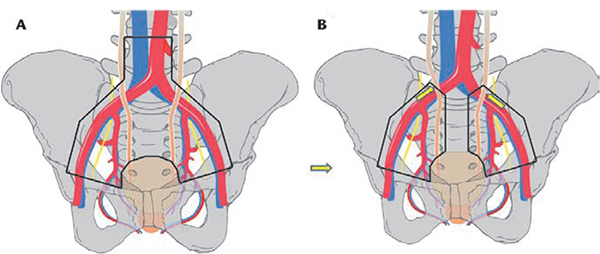

Figure 2. (A) Super-extended pelvic lymph node dissection template (levels I, II, and III). (B) Standard/extended template (level I plus level II up to crossing of ureter and external iliac artery). Adapted from Zehnder P et al.11

… in order to evaluate the benefit of extended PLND while avoiding a false-positive due to the Will Rogers phenomenon, one must evaluate survival in node-negative and node-positive patients in aggregate.

… although oncologic outcomes after RC may be associated with the extent of PLND, other lymph node-associated factors are prognostic for survival after surgery.

As we await definitive prospective evidence, one approach is to use a risk-adapted approach to determine the appropriate PLND template.

Main Points

• Numerous different templates exist to guide surgeons in pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND). However, no level I evidence exists to address the value of one dissection template over another; published guidelines, therefore, are vague.

• Investigators have evaluated the staging utility and oncologic benefits of extended PLND with regard to lymph node yield, rather than analyzing outcomes according to particular anatomic PLND templates. Lymph node yields are highly variable and depend on multiple factors, however, limiting their utility as a standard threshold metric for the adequacy of PLND at radical cystectomy (RC).

• Two prospective randomized trials are underway to assess whether an extended PLND template at RC is associated with improved cancer-specific survival and overall survival.

• It is plausible that a larger dissection is associated with important incremental costs and an increased number of complications and side effects. Yet evidence to inform physicians and patients about the morbidity of extended PLND is limited.

Main Points

• Numerous different templates exist to guide surgeons in pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND). However, no level I evidence exists to address the value of one dissection template over another; published guidelines, therefore, are vague.

• Investigators have evaluated the staging utility and oncologic benefits of extended PLND with regard to lymph node yield, rather than analyzing outcomes according to particular anatomic PLND templates. Lymph node yields are highly variable and depend on multiple factors, however, limiting their utility as a standard threshold metric for the adequacy of PLND at radical cystectomy (RC).

• Two prospective randomized trials are underway to assess whether an extended PLND template at RC is associated with improved cancer-specific survival and overall survival.

• It is plausible that a larger dissection is associated with important incremental costs and an increased number of complications and side effects. Yet evidence to inform physicians and patients about the morbidity of extended PLND is limited.

As described by Whitmore and Marshall in 1962,1 the original pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) template during radical cystectomy (RC) included nodal/lymphatic tissue bounded by the external iliac artery, the distal ureter, and Cooper's ligament. The nodal tissue enveloping the external iliac vein and occupying the obturator fossa nodes was also removed, followed by removal of the lymphatic tissue surrounding the internal iliac vessels and posterior pelvis, including presacral nodes.2

In the ensuing decades, urologists at different centers have modified the original template. However, to date, no level I evidence exists to address the value of one dissection template over another; published guidelines, accordingly, are vague.3 Several names have been given to different templates and nodal regions. The limited template includes perivesical nodes and lymphatic tissue in the obturator fossa, limited laterally by the external iliac vein and medially by the obturator nerve.4-6 A larger limited lymphadenectomy template (referred to as standard by some) is bounded distally by the circumflex iliac vein and Cloquet's node, laterally by the genitofemoral nerve, medially by the bladder and internal iliac vessels, posteriorly by the obturator fossa, and proximally by the bifurcation of (or distal aspect of) the common iliac artery.5-8

Extended PLND has been variously defined to include a more cephalad proximal boundary located at or above the aortic bifurcation and may also include presacral and presciatic nodes.7,9,10 The extended template bounded proximally by the crossing of the ureter and external iliac artery6,11 is referred to as standard/extended in this review. Still others define the extended template to extend as proximally as the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery and also include lymphatic tissues in the triangle of Marcille, which involves medial retraction of the external iliac artery to reveal the space medial to the psoas major; dissection of this space reveals the proximal aspect of the obturator nerve as it emanates from the psoas.4,11,12

An alternative nomenclature system for PLND defines three levels of operative intervention: levels I, II, and III (Figure 1).13 The level I template is similar to a standard template—the proximal extent of this is the common iliac bifurcation. Level II nodes are lateral to the common iliac artery, include presacral nodes, and extend proximally to the aortic bifurcation. Level III nodes are located between the ureters and great vessels and extend proximally to the inferior mesenteric artery. Investigators have also referred to super-extended PLND, which is the template that would include all level I, II, and III nodes (Figure 2).2,11,14

Mapping Studies of the Bladder's Lymphatic Drainage

Evidence supporting the extent of PLND has been sought by several investigators. In their seminal 2004 article, Leissner and colleagues13 studied 290 patients who had super-extended PLND (thereby defining level I, II, and III nodes). Lymphatic tissue from each patient was submitted in 12 packets corresponding to distinct anatomic sites, and nodes were examined with routine diagnostic histopathology tissue processing and microscopy; 28% of patients were found to have lymph node metastases. Among these patients, 56% of positive lymph nodes were in the level I packets, 27% in level II, and 17% in level III. Among patients with a single positive lymph node (pN1), however, the positive node was in level I in 89% of cases, in level II in 10%, and never in level III. These results suggest that if a sentinel lymph node can be identified that is relevant for patients with invasive bladder cancer, it is located at or below the aortic bifurcation. Thus, if PLND is performed purely for staging purposes to differentiate patients who are node-negative versus node-positive, there is limited utility to expanding the PLND template above the aortic bifurcation, as patients with a single lymph node metastasis are extremely unlikely to have a positive node in level III. Put another way, the probability of a “skip lesion” (negative pelvic nodes, positive pelvic node above aortic bifurcation) is extremely low.

In a subsequent study, Vazina and colleagues15 reported on the pattern of lymph node metastases in 176 consecutive cystectomy patients, 92% of whom had dissections carried proximally just above the aortic bifurcation. Although 18% of patients had positive nodes located in the aortic or common iliac packets, only 1 of 43 patients with node-positive disease was found to have negative pelvic nodes but a positive common iliac node.

Roth and associates16 reported on a series of 60 patients with T1-3 N0 M0 bladder cancer who under-went transurethral injection of a radiotracer 1 day prior to RC with PLND.16 Postinjection single-photon emission computed tomography and intraoperative handheld gamma-probe guidance were used to identify and remove suspicious lymph nodes, followed by back-up PLND carried proximally to the ureter and common iliac artery. Here, 8% of patients had tumor-involved lymph nodes in the proximal common iliac packets (above the ureter) and in the para-aortic and paracaval packets (above the aortic bifurcation). However, all of these patients also had positive pelvic nodes (external iliac, obturator, and internal iliac packets). The authors also found that 42% of internal iliac lymph nodes are located medial to the vessel, a finding that has caused some authors to advocate for dissection of the presacral lymph nodes in an optimal PLND template.2

Bilateral PLND is widely accepted over unilateral PLND in bladder cancer given the substantial crossover that exists for lymph node metastasis. Mapping studies reveal that even in patients with discrete, geographically lateralizing bladder tumors, lymphatic drainage of the bladder is bilateral in approximately 40%.12,17,18

Assessment of PLND Extent

The assessment of the quality of nodal dissection has been a subject of recent interest and has been proposed as a potential quality metric to guide reimbursement practices. However, assessment of adequacy and extent of the nodal dissection is challenging. Multiple investigators have evaluated the staging utility and oncologic benefits of extended PLND with regard to lymph node yield19-20 (the number of lymph nodes removed at cystectomy) as opposed to analyzing outcomes according to particular anatomic PLND templates. Lymph node yields are highly variable and depend on multiple factors, limiting their utility as a standard threshold metric for the adequacy of PLND at RC. Lymph node yield varies among different surgeons, different pathologists, different institutions, by age, and even by the number of tissue packets submitted.13-20,24 For example, the nodal yield from a cadaveric study of super-extended PLND demonstrated great variability, ranging from 10 to 53 nodes.25 Similarly, the range of lymph node yield in one study of 60 patients who uniformly under-went standard PLND was 13 to 72, underscoring the great variability in lymph node yield among patients.16 On the other hand, assessment of the PLND according to the surgeon's stated anatomic template is subject to misrepresentation and lacks an objective measurement for quality control. In the current phase III trial, Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 1011, a composite review of pathologic data (lymph node counts and packet submission), operative reports, and intraoperative photos are used to objectively monitor the completeness of the dissection.

Associations of PLND Template With Survival After RC

Due to the potential for many confounding factors and systemic biases, only a prospective randomized controlled trial will be able to answer whether an extended PLND template at RC is associated with improved cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS). Fortunately, two such trials are ongoing, SWOG 1011 and the German Association of Urologic Oncology trial, both of which feature 1:1 randomization comparing super-extended PLND (levels I, II, and III nodes) to standard PLND (level I nodes).23

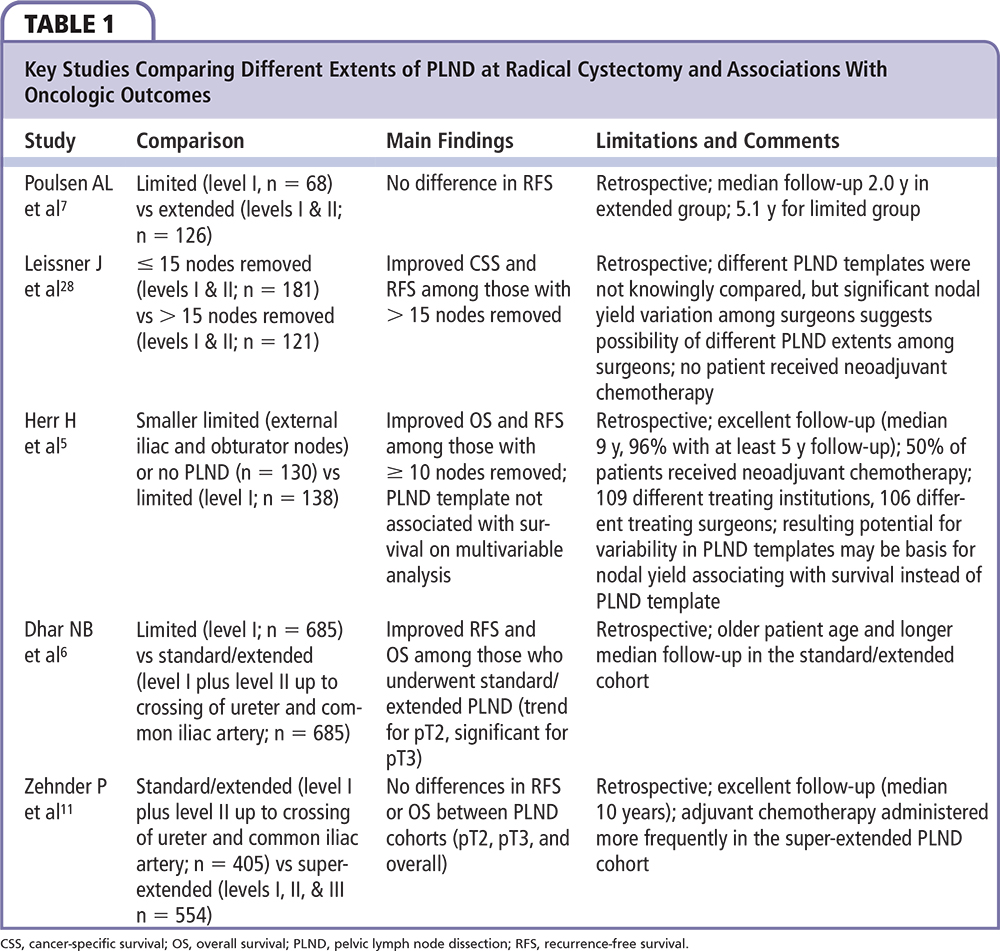

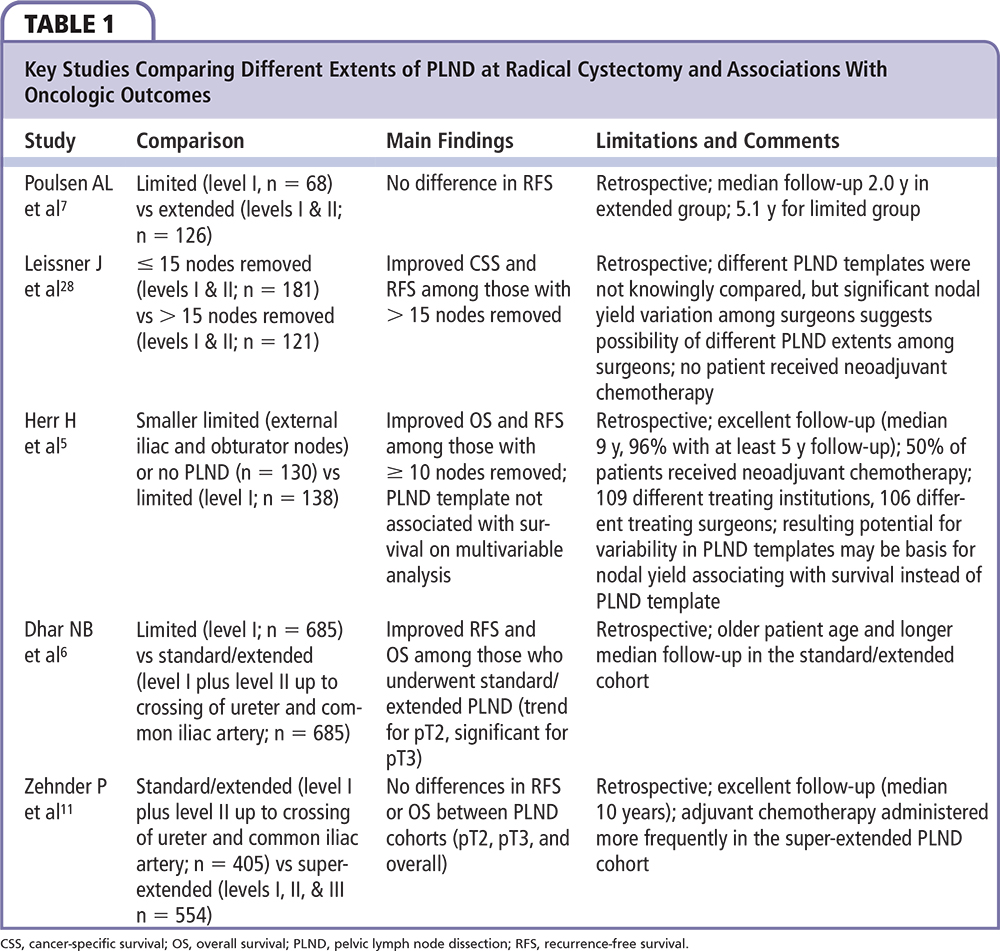

Although trial results will be crucial, the current body of comparative literature provides multiple important insights into optimizing the extent of PLND at RC. In 1998, Poulsen and associates7 published their results on limited (level I) versus extended (levels I and II) PLND in a retrospective series of 194 patients who underwent RC at a single center. No difference in recurrence-free survival (RFS) overall was identified, but the pN0 subgroup did appear to have improved RFS. This may be explained by a Will Rogers phenomenon, in which a larger PLND template can reclassify a patient with limited nodal disease from pN0 if he had undergone limited PLND to node-positive with extended PLND.23,26,27 The net effect of such reclassification would be to improve apparent survival in both node-negative and node-positive groups by placing intermediate-prognosis patients from a favorable category into a poor prognostic category.

Thus, in order to evaluate the benefit of extended PLND while avoiding a false-positive due to the Will Rogers phenomenon, one must evaluate survival in node-negative and node-positive patients in aggregate. In 2000, Leissner and colleagues28 reported on a series of 302 patients who underwent RC with extended PLND (levels I and II), finding that patients who had > 15 nodes removed had improved CSS compared with those with ≤ 15 nodes removed, both when node-negative and node-positive patients were analyzed separately and when all patients were analyzed in aggregate (univariate). Herr and colleagues,5 similarly, found that patients who had a more extensive PLND (defined as ≥ 10 nodes removed) had improved overall survival after RC after adjusting for receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, pathologic stage, and soft-tissue margin status.

In 2008, Dhar and colleagues6 found that PLND template did not affect survival for patients with pT2 lesions; however, those with pT3 lesions did experience a 20% to 30% absolute 5-year RFS and OS advantage with standard/extended versus limited PLND. This finding has led some authors to conclude that extended PLND is the truly optimal template at RC.29 Further, this key study suggests that T3 patients should undergo extended PLND in a risk-adapted approach.

In 2011, Zehnder and coworkers11 published their findings comparing 959 patients who underwent RC with either standard/extended PLND at the University of Bern (Switzerland) or super-extended PLND (levels I, II, and III) at the University of Southern California (Los Angeles). None of the patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Over a median follow-up of 10 years, there were no differences in RFS between the two groups. Taken together with the findings from Dhar and colleagues,6 findings from retrospective studies suggest that a limited PLND is oncologically suboptimal, and, although super-extended PLND may improve detection of tumor-involved lymph nodes, a standard-extended PLND template carried proximally to the crossing of the ureter over the common iliac artery (as performed at the University of Bern) appears to be oncologically adequate. Of note, the Bern PLND template does include removal of some but not all of the presacral nodes excluding tissue in the vicinity of hypogastric nerve fibers immediately caudal to the aortic bifurcation.6,11

What is the basis for extended PLND to lead to survival benefit for patients undergoing RC? It is possible that a larger PLND template that removes histologically negative nodes may actually be reducing (or eradicating) micrometastatic disease at the time of RC. The prevalence of micrometastatic disease in histologically negative nodes may be as high as 20% to 35% based on real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction-based studies of several bladder cancer markers (FXYD3, KRT20, cytokeratin 18, and uroplakin II).30,31 The clinical significance of histologically undetectable micrometastatic disease is unknown, however. Although there are important studies that compare oncologic outcomes with differing PLND templates (Table 1), this retrospective evidence is not definitive, is limited by potential confounders and biases, and will ultimately be supplanted by results of ongoing prospective trials.

Associations of Other Lymph Node Factors With Survival After RC

It is noteworthy that although oncologic outcomes after RC may be associated with the extent of PLND, other lymph node-associated factors are prognostic for survival after surgery. For example, the precise burden of lymph node metastases is prognostic, as reflected in current pathologic staging: N1, N2, and N3.15,18,23,32 Fleischmann and coworkers,33 examining 507 patients who underwent RC for clinically localized bladder cancer, found that burden of lymph node tumor involvement was prognostic for RFS and OS. In particular, survival advantages were noted for pN1 (vs pN2), < 5 positive nodes, lymph node density < 20%, and absent extracapsular (extranodal) extension (ENE). Among these factors, presence of ENE was the worst prognostic factor and the only significant adverse predictor on multivariable analysis, even after adjusting for nodal tumor burden and pT3 disease. Similarly, Mills and colleagues18 found in an earlier report that ENE was significantly associated with worse OS after adjusting for receipt of adjuvant therapy and number of positive lymph nodes.

In a multi-institutional retrospective analysis of 750 patients who underwent RC, Lotan and associates34 showed that both lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and lower absolute nodal yield were associated with significantly worse RFS, CSS, and OS. A more recent multicenter retrospective analysis examined ENE, LVI, and lymph node yield of 748 patients who underwent PLND to varying extents. Fajkovic and coauthors35 showed that although the number of positive lymph nodes and lymph node density at RC were negative prognostic indicators on univariate analysis, ENE, LVI, positive soft tissue margins, and pT stage were significantly associated with worse RFS and cancer-specific survival in multivariable analyses. Interestingly, in this study, number of lymph nodes removed at RC was significantly associated with survival after RC (P ≤ .001) in the subgroup analysis of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy. However the hazard ratios for RFS (1.02) and cancer-specific survival (1.02) were quite low compared with ENE (1.97-2.03). These findings confirm the aforementioned notion that absolute lymph node yield is not important in assessing the adequacy of PLND at RC, but they also call into question whether associations of improved survival with extended PLND are the result of type I errors in retrospective analyses and/or possible unmeasured confounding when ENE and LVI are not incorporated into multivariable models.

Balancing Potential Benefits With Costs: What Are the Morbidities of a Larger PLND Template?

It is intuitive that a larger dissection is associated with important incremental costs as well as an increased number of complications and side effects. Yet evidence to inform physicians and patients about the morbidity of extended PLND is limited. In a comparison between two European centers using different PLND templates, patients who underwent super-extended PLND (compared with limited PLND) had prolonged surgeries (by 63 min) but overall complications were similar between groups.4 In this study there were no adjustments for age, comorbidity, and urinary diversion type, however. Others agree that a super-extended dissection entails about 1 additional hour of procedure time compared with a limited or standard template.13 Though super-extended PLND is also feasible during robotic RC,36 comparative safety and complication data are unknown.

As an example of the unexpected results that can emerge with comparative research, it is useful to consider the results of variable node dissection templates in other solid malignancies. Gastrectomy with extended (D2) regional lymph node dissection was the standard treatment of curable gastric cancer in Asia for decades. Due to a 10% to 30% rate of para-aortic node involvement, however, an additional para-aortic nodal dissection (PAND) was initiated in the 1980s for patients with advanced disease. A pivotal randomized controlled trial compared the survival benefit of adding the PAND to the D2 lymphadenectomy.37 Strikingly, no differences were observed in survival but the overall incidence of surgery-related complications was 20.9% in the D2 lymphadenectomy group and 28.1% in the D2 lymphadenectomy plus PAND group (P = .07).

Dissection of the retroperitoneum between the aortic and iliac bifurcations may disrupt regional sympathetic nerve fibers.16-18 However, the functional implications of this are unknown and this morbidity has not yet been quantified. Lymphoceles may be related to more extensive PLNDs, but in several series there was no difference in detected lymphocele rates (l%-2%) after RC between patient groups who underwent limited versus extended PLND.4,7,28 It is unknown if extended PLND truly has no additional risk of lymphatic leak as asymptomatic lymphoceles in retrospective studies may have gone undetected, thus limiting the validity of these estimates.

Risk-adapted Approach to Determine PLND Extent

Comparative retrospective evidence suggests that a standard-extended PLND template may be oncologically adequate, whereas a super-extended template may lead to increased detection of lymph node metastases; however, data from randomized controlled trials are lacking. As we await definitive prospective evidence, one approach is to use a risk-adapted approach to determine the appropriate PLND template. For example, it is known that the likelihood of nodal disease increases with pT category (22% or less for ≤ pT2 vs 40% or more for ≥ pT3),13 which has been confirmed in numerous other studies.14,38 Further, the aforementioned study by Dhar and colleagues6 shows that, although standard-extended PLND may not lead to an RFS advantage for those with ≤ pT2 disease, it does lead to measurable survival gains in the cohort with ≥ pT3 lesions. Shariat and colleagues38 have also demonstrated that LVI is associated with a higher probability of nodal metastases; therefore, patients whose transurethral tumor biopsies feature LVI may be considered to be higher risk and therefore benefit from a more extended PLND template.

A risk-adapted strategy may also incorporate patient age and comorbidities into the decision process, as it is plausible that older and increasingly comorbid patients may be less likely to tolerate an extended PLND and may also accrue a lower marginal RFS benefit due to mortality from competing risks.39

Thus, should patients suspected of having T3 disease or LVI (or preoperative features such as deep muscle invasion or hydronephrosis) selectively undergo a more extended PLND at RC? The answer to this is unknown in light of current evidence. An important limitation is that pathologic upstaging at RC is largely unpredictable.40 Furthermore, up to 40% and 60% of patients with pT2 and pT3 disease recur within 5 years, respectively,41 which suggests the possibility of disseminated disease that was under staged prior to RC. Whether simply expanding the PLND template will lead to measurable oncologic gains regardless of each patient's risk profile is an unanswered question. Ultimately, results of ongoing clinical trials will provide invaluable guidance. ![]()

The authors report no real or apparent conflict of interest.

References

- Whitmore WF Jr, Marshall VF. Radical total cystectomy for cancer of the bladder: 230 consecutive cases five years later. J Urol. 1962;87:853-868.

- Herr HW. Extent of pelvic lymph node dissection during radical cystectomy: where and why! Eur Urol. 2010;57:212-213.

- Witjes JA, Compérat E, Cowan NC, et al. Radical cystectomy—technique and extent. In: Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer Guidelines. European Association of Urology; 2013:40.

- Brössner C, Pycha A, Toth A, et al. Does extended lymphadenectomy increase the morbidity of radical cystectomy? BJU Int. 2004;93:64-66.

- Herr HW, Faulkner JR, Grossman HB, et al. Surgical factors influence bladder cancer outcomes: a cooperative group report. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22: 2781-2789.

- Dhar NB, Klein EA, Reuther AM, et al. Outcome after radical cystectomy with limited or extended pelvic lymph node dissection. J Urol. 2008;179:873-878.

- Poulsen AL, Horn T, Steven K. Radical cystectomy: extending the limits of pelvic lymph node dissection improves survival for patients with bladder cancer confined to the bladder wall. J Urol. 1998;160(6 Pt 1): 2015-2019.

- Mills RD, Fleischmann A, Studer UE. Radical cystectomy with an extended pelvic lymphadenectomy: rationale and results. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16:233-245.

- Stein JP, Cai J, Groshen S, Skinner DG. Risk factors for patients with pelvic lymph node metastases following radical cystectomy with en bloc pelvic lymphadenectomy: concept of lymph node density. J Urol. 2003;170:35-41.

- Steven K, Poulsen AL. Radical cystectomy and extended pelvic lymphadenectomy: survival of patients with lymph node metastasis above the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels treated with surgery only. J Urol. 2007;178(4 Pt 1):1218-1223.

- Zehnder P, Studer UE, Skinner EC, et al. Super extended versus extended pelvic lymph node dissection in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a comparative study. J Urol. 2011;186:1261-1268.

- Abol-Enein H, El-Baz M, Abd El-Hameed MA, et al. Lymph node involvement in patients with bladdercancer treated with radical cystectomy: a pathoanatomical study—a single center experience. J Urol. 2004;172(5 Ptl):1818-1821.

- Leissner J, Ghoneim MA, Abol-Enein H, et al. Extended radical lymphadenectomy in patients with urothelial bladder cancer: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Urol. 2004;171:139-144.

- Burkhard FC, Roth B, Zehnder P, Studer UE. Lymph-adenectomy for bladder cancer: indications and controversies. Urol Clin North Am. 2011;38:397-405.

- Vazina A, Dugi D, Shariat SF, et al. Stage specific lymph node metastasis mapping in radical cystectomy specimens. J Urol. 2004;171:1830-1834.

- Roth B, Wissmeyer MP, Zehnder P, et al. A new multimodality technique accurately maps the primary lymphatic landing sites of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2010:57:205-211.

- Roth B, Zehnder P, Birkhäuser FD, et al. Is bilat eral extended pelvic lymphadenectomy necessary for strictly unilateral invasive bladder cancer? J Urol. 2012:187:1577-1582.

- Mills RD, Turner WH, Fleischmann A, et al. Pelvic lymph node metastases from bladder cancer: outcome in 83 patients after radical cystectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. J Urol. 2001;166:19-23.

- Koppie TM, Vickers AJ, Vora K, et al. Standardization of pelvic lymphadenectomy performed at radical cystectomy: can we establish a minimum number of lymph nodes that should be removed? Cancer. 2006:107:2368-2374.

- Herr H, Lee C, Chang S, Lerner S; Bladder Cancer Collaborative Group. Standardization of radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection for bladder cancer: a collaborative group report. J Urol. 2004:171:1823-1828.

- Parkash V, Bifulco C, Feinn R, et al. To count and how to count, that is the question: interobserver and intraobserver variability among pathologists in lymph node counting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:42-49.

- Bochner BH, Herr HW, Reuter VE. Impact of sepa rate versus en bloc pelvic lymph node dissection on the number of lymph nodes retrieved in cystectomy specimens. J Urol. 2001;166:2295-2296.

- Morgan TM, Kaffenberger SD, Cookson MS. Surgical and chemotherapeutic management of regional lymph nodes in bladder cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:1081-1088.

- Meijer RP, Nunnink CJ, Wassenaar AE, et al. Standard lymph node dissection for bladder cancer: significant variability in the number of reported lymph nodes. J Urol. 2012:187:446-450.

- Davies JD, Simons CM, Ruhotina N, et al. Anatomic basis for lymph node counts as measure of lymph node dissection extent: a cadaveric study. Urology. 2013:81:358-363.

- Gofrit ON, Zorn KC, Steinberg GD, et al. The Will Rogers phenomenon in urological oncology. J Urol. 2008:179:28-33.

- Schmid HP, Engeler DS. Words of wisdom. Re: D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;56:744-745.

- Leissner J, Hohenfellner R, Thüroff JW, Wolf HK. Lymphadenectomy in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder; significance for staging and prognosis. BJ U Int. 2000;85:817-823.

- Bochner BH, Tarin T. Words of wisdom. Re: Outcome after radical cystectomy with limited or extended pelvic lymph node dissection. Eur Urol. 2010;57:175.

- Kurahashi T, Hara I, Oka N, et al. Detection of micrometastases in pelvic lymph nodes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for locally invasive bladder cancer by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR for cytokeratin 19 and uroplakin II. Clin Cancer Res. 2005:11:3773-3777.

- Marín-Aguilera M, Mengual L, Burset M, et al. Molecular lymph node staging in bladder urothelial carcinoma: impact on survival. Eur Urol. 2008; 54:1363-1372.

- Tarin TV, Power NE, Ehdaie B, et al. Lymph node-positive bladder cancer treated with radical cystectomy and lymphadenectomy: effect of the level of node positivity. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1025-1030.

- Fleischmann A, Thalmann GN, Markwalder R, Studer UE. Extracapsular extension of pelvic lymph node metastases from urothelial carcinoma of the bladder is an independent prognostic factor. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2358-2365.

- Lotan Y, Gupta A, Shariat SF, et al. Lymphovascular invasion is independently associated with overall survival, cause-specific survival, and local and distant recurrence in patients with negative lymph nodes at radical cystectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6533-6539.

- Fajkovic H, Cha EK, Jeldres C, et al. Extranodal extension is a powerful prognostic factor in bladder cancer patients with lymph node metastasis. Eur Urol. 2013;64:837-845.

- Desai MM, Berger AK, Brandina RR, et al. Robotic and laparoscopic high extended pelvic lymph node dissection during radical cystectomy: technique and outcomes. Eur Urol.2012;61:350-355.

- Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, et al; Japan Clinical Oncology Group. D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:453-462.

- Shariat SF, Rink M, Ehdaie B, et al. Pathologic nodal staging score for bladder cancer: a decision tool for adjuvant therapy after radical cystectomy. Eur Urol.2013;63:371-378.

- Koppie TM, Serio AM, Vickers AJ, et al. Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity score is associated with treatment decisions and clinical outcomes for patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Cancer.2008;112:2384-2392.

- Skinner EC, Sagalowsky AI. Is extended lymphadenectomy of beneficial therapeutic value for T2 urothelial cancer? J Urol. 2014;191:1206-1208.

- Zlotta AR. Limited, extended, superextended, megaextended pelvic lymph node dissection at the time of radical cystectomy: what should we perform? Eur Urol. 2012;61:243-244