Marshall McLuhan’s famous dictum tells us that the form of a medium is inherently part of the message itself. Content in printed magazine form, for example, dictates many aspects of the story—from its written style and word count to the subtleties of fixed page design. The shape of a “story container” leaves its mark on the story itself.

Now, however, as media channels mix, merge, and multiply at breakneck speed, the idea of format-free content is an attractive one. If only content could be created once and output more or less automatically to multiple channels. To test the practical implications of that idea, we spoke with a number of publishers. At the heart of our discussion were content authoring and management technology, plus the chicken-and-egg question that makes modern content strategy so difficult.

It’s About the Story

We spoke with two traditional magazine publishers (Source Interlink and Forbes) and two pure-play digital companies (Say Media and Glam). Although the four represent wildly diverse audiences and demographics, some common themes and strategies emerged. Most agree that effective narrative remains as the essential ingredient for success, no matter how strange and distracting the various media channels and platforms may seem. “The tools and tricks change with the medium, but the fundamentals of storytelling never do,” says Say Media’s CTO David Lerman. “Great storytelling is great storytelling, whether it’s on a tablet or a cave wall.”

Each company we interviewed is embracing the disruptive nature of an always-connected audience, both in terms of content creation technology and in dealing with the implications for its writers and editors. The traditional publishers are concerned about the continuing role of print, but are remarkably upbeat about it. “Long term, the future of print is as a premium format,” says Source Interlink’s chief content officer Angus MacKenzie. He notes that the diversity of brand-centered content made possible by new media platforms can now be curated to produce a vastly superior “best of” printed edition. Such a product, he reasons, would have enduring financial value to subscribers and advertisers.

Content curation is also a common theme. Glam Media CEO Samir Arora notes that only professionally created content—curated for quality and discoverability—could create lasting value for a brand. “Social collecting, sharing, and remixing of information can be done by any consumer,” he says. “Content creation should be from professional content businesses, authors, and studios.”

Expertise Matters

We spoke with Forbes Media’s chief product officer Lewis D’Vorkin, who is enthusiastic about both the core expertise of the company’s content creators and the technology they use. Forbes writers, editors, and contributors use the company’s Falcon publishing platform and a customized version of WordPress to create and edit content. Users may search for details of their own and related content, incorporate photos from a secure library, embed elements such as video, and publish selected content to Forbes channels and social media. The permissions-based, on-screen editing tools have significantly compressed journalistic time frames, and extended the reach of Forbes’ team of journalists and contributors, D’Vorkin notes.

Although the right tools are important, D’Vorkin emphasizes that a rigorous onboarding process has resulted in the team of experts who are at the heart of Forbes’ content strategy. “Once we vet contributors, we give them the tools to self-publish, without there being a gatekeeper in the way,” he says. “Our system, both human and technological, is designed to monitor content very carefully and quickly—after publishing it.”

Part of the feedback involves subscriber feedback, which each content creator is required to monitor. “In every layer of our system, there is a built-in ‘meritocracy filter,’ which includes the audience,” he adds. “Our commenting system requires that the author engage with comments from the community. He or she can simply say ‘yes, I approve this comment,’ meaning that it’s productive, or disagrees with me in a productive way, or it takes the story forward.” Once the author approves the comment, it’s displayed with the article by default. “You can find the comments of anybody who’s just yelling, screaming, and being irrational, if you want, but it’s an extra click,” D’Vorkin says. “Because of that system, most people have figured that out. They then decide not to comment—unless they’re going to bring their A game.”

This process is the beginning of what D’Vorkin calls a “reputation system.” Beyond the simple yes/no approval of comments by writers, he believes a more sophisticated ranking process is possible. “A commenter who is frequently being approved, is active across related verticals, and is very clearly engaged and read by others, could be rated almost as high as one of our contributors,” he says. “Their comments could automatically go live, which could take the burden somewhat off the writer.” While the capability is not yet part of the Forbes system, D’Vorkin noted that it would not be too difficult, since the analytics of reader activity and content viewing are readily available.

D’Vorkin acknowledges the impact of small-screen devices on the way content is presented. For smartphones, Forbes uses an approach D’Vorkin refers to as “info cards”—blocks of top-level story information including the headline and first sentence—which the reader can easily swipe through, and click to read further, if a story is of interest. “That’s more of a truncation than an editorial synopsis,” he says. “It’s currently an automatic process, based on character count, but I can envision something more visual—more magazine-like—going forward.”

One aspect of content that has changed significantly in the digital era is the opening, according to D’Vorkin. “Years ago, I would never have begun a thought leadership piece with ‘I’ or ‘my.’ Now I do it all the time. People want to get right to ‘what does this guy think?’” He points out that the old newspaper practice of putting who-what-when-where-how in the opening paragraph is rare today. “Content is becoming more like letters we write to one another, rather than news stories. People identify with individual voices and brands,” he says. The upside of this change is an increase in engagement. It also attracts an audience that is more attractive to advertisers and sponsors. “Forbes material is the most consistently shared expert content on LinkedIn, month after month.”

On the issue of sponsored content, D’Vorkin feels that audiences care more about accuracy, authenticity, expertise, and especially transparency than they do about whether the source is a journalist, an author, a responder, a contributor, or a marketer. “If you know your stuff, you have nothing to fear,” he says. “If you’re faking it, there’s always someone out there who knows better than you, and is not afraid to say so.”

It’s the Brand, Not the Platform

Source Interlink Media is the home of several well-known automotive and lifestyle brands. CCO Angus MacKenzie, formerly Motor Trend’s editor-in-chief, has a wide range of media experience on three continents, and has been dealing with change for many years. When he took over Motor Trend in 2004, he grappled with the print/web dilemma, deciding ultimately not to withhold print content from the website. “There is a difference in both consumption behaviors and audience on each platform, and there has been an overall decline on the print side,” he says, “but not as much as people feared. We learned quickly that on the Internet you needed quality content in quantity.”

MacKenzie believes strongly that value is not inherent in any platform, per se, but in the content—contrary to what early Internet publishing analysts believed. Another early mistake, he feels, was the notion that the purpose of digital content was to drive customers to the print product. “The trick is when you have an audience, you monetize them on the platform they’re using.”

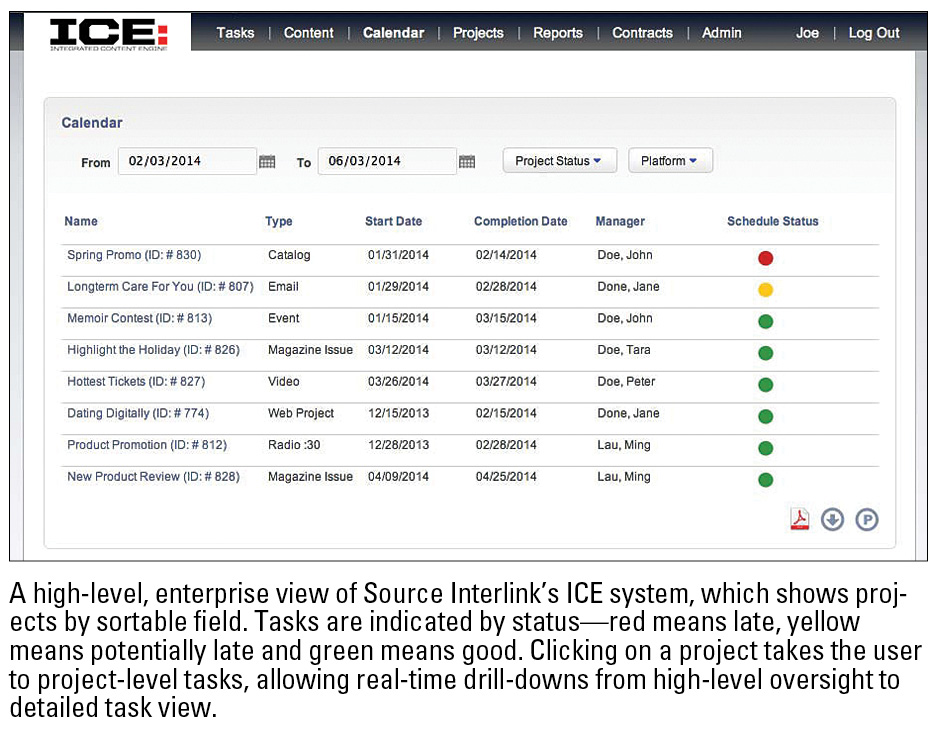

Source Interlink is moving to a “web-led, socially amplified approach to content creation and distribution,” according to MacKenzie. Because the company’s 50 different brands were the result of many acquisitions, they had a large number of legacy content management and authoring systems. Now, however, they are working on a single CMS approach, called an Integrated Content Engine, which will simplify web content curation, social sharing, and qualification of the best content for print and tablet editions. MacKenzie stressed that the change was more about a mindset than a technology, however.

Another important change is the creation of what MacKenzie calls “super sites.” These include thematically-related brands, each with its own print and digital channels, but collectively garnering more traffic and engagement than the sum of their individual sites. Each super site is overseen by a single content director, whose job it is to find and exploit common stories and events via each brand’s social media following, and to figure out what deliverables work best for each channel or platform.

MacKenzie has found that team composition and strategy leads to successful multi-channel content creation. The best team, he believes, includes a combination of experts or enthusiasts (capable of writing insightful and entertaining pieces) with newspaper-trained editors and reporters (geared to create immediate news elements by whatever channel can reach the audience quickest).

An example of this is an automotive product rollout event, MacKenzie explains. Traditionally, magazine writers would attend a live event, where packets of material would be distributed, interviews held, and in-depth analysis written and published. Today, however, much more of the material is made available in advance and online, so the in-depth piece can often be pre-written. The event is still important, however, since it becomes the venue for social media. For brands with a substantial following, content creators can utilize micro-blogs, photo sharing, and online video to create a unique and more personal “you are there” narrative—always pointing the follower back to the in-depth content and its related advertising.

The triumph of brand over platform was illustrated by Hot Rod magazine. Its print readership was largely over-50 males, who built and raced their cars in their teens. However, a recent YouTube series attracted an entirely new demographic, very few of whom subscribed to the print publication. However, MacKenzie points out that Hot Rod’s many YouTube channel followers have become an attractive audience for sponsors, and consequently have generated substantial revenue.

MacKenzie’s advice to publishers is simple. “It’s about changing the culture among journalists and editors, not obsessing about the platform,” he says. “The platform is important, and you have to figure out how to support it. However, it’s a 24/7 non-stop world, regardless of what people are reading. The audience wants to interact with the brand; it’s not up to you to decide where or how they should do it.”

Exploring the Ecosystem

Glam Media’s CEO Samir Arora describes the ideal publishing environment as an ecosystem, not a platform, per se. The company’s many fashion, food, and lifestyle brands now boast over two million combined pieces of curated and discovery-optimized content. Arora also notes that much of the content is evergreen in nature, adding value for advertisers and sponsors.

Glam’s content creation technology is based on open standards and free, commonly available tools, supplemented by their 2011 purchase of the highly-customizable social network environment Ning. Writers, editors, video and multimedia producers, and curators, can create and submit content, often directed by Glam, which issues event, trend, and subject matter guidance—including hashtagged keywords. Content creators can choose to publish only a link to their site, or negotiate with Glam to host the content, for a fee, while still retaining ownership. Glam collects and curates partner content, selects which content should be featured within a specific brand, and makes it available through what Arora describes as “multi-stream distribution.” The Glam system uses device-independent net objects, as opposed to fixed-page formats, to generate native app content for tablets and smartphones.

The number of Glam’s partners has grown dramatically since 2004, when there were only 12 content creation businesses. According to Arora, the number now stands at over 6,000. Over the past five years, Glam has paid more than $200 million to its content creator partners.

According to Arora, Glam is following a model similar to that of Netflix, with a goal of about 10-20 percent commissioned or authored content (owned by Glam) and the remainder consisting of licensed distribution of content from its partners. Currently, all the data-driven content is free, attracting a wide variety of sponsors and advertisers to each highly focused (and very social media-aware) brand following. Arora indicates that Glam is considering some additional revenue models for the future, including in-app purchasing, special editions, and possibly paid subscriptions.

The changes in content consumption on various media and devices are largely dictated by human behavior. “Early in the day, I may want to search for articles or video, but late at night, with my iPad, I may want a package of content delivered to me because I’m too tired to search,” he says. “When choosing our targeted categories and sub-categories, we started with behavioral patterns, because that’s what we knew best, and now we’ve added time-based delivery of different content and formats.”

Arora emphasized that magazine publishers’ strengths—the art of creating and curating high-quality content—translate directly to the digital world. However, “what changes is the format, the distribution model, and the technology,” he says. “It’s not just about requiring editors to do more blogging.

“TV studios usually get our approach faster than traditional magazines do, because they’re already producing and licensing shows for distribution. However, there’s no reason why a magazine could not be a content partner as well.”

Say the Word

David Lerman of Say Media is very critical of the current digital advertising system. It is “optimized for cheap distribution of crappy banner ads that serve neither readers nor advertisers. As a result, there is a lot of pressure on publishers to ‘play the game,’ pushing cheap listicles and slideshows and plastering their sites with ads. As an industry, we need to move beyond this adolescence of digital publishing by creating great content, building beautiful sites, offering better ad products, and helping advertisers see how higher quality content benefits them.”

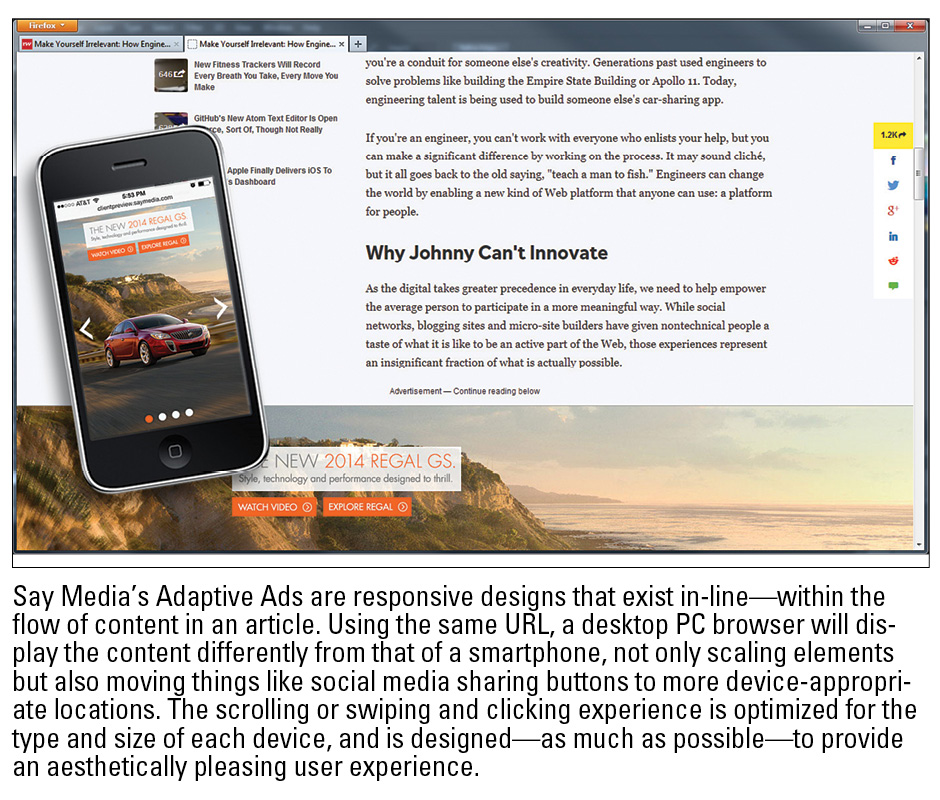

Say Media boasts a number of pure play digital brands, including xoJane, ReadWrite, and Remodelista. Writers, editors, advertisers, and others generate content in a proprietary system developed by Say Media: Tempest. According to Lerman, the platform offers integrated tools for original content writers and editors, as well as social media participants, while handling the commerce and marketing elements, as well as multi-device distribution and analytics.

Lerman argues that content will probably always be influenced by the nature of its format or device, although systems like Tempest can ease the burden of content creation. “It’s certainly possible to create content that can be automatically reformatted to fit its container. However, in dumbing down content to be ‘format-free,’ we often sacrifice beauty, design, and utility.”

He continues, “Why are printed magazines so often better designed than websites, despite the web giving us infinitely richer tools to tell a story? It’s because the magazine was thoughtfully laid out and designed, while the digital content was stripped of its design elements and forced into a generic template.

“Digital content still needs to come into its own. We need better tools to tell stories that take advantage of all the medium offers—and I suspect that will always make the dream of ‘create once, output multiple’ an elusive one.”

Like his counterpart at Forbes, Lerman notes that an author’s job is no longer over once the article is published. Responses to comments, ongoing engagement with readers, and cultivation of a following—both the author’s and the brand’s—are ongoing tasks.

Chicken AND Egg

Clearly, writers and editors need to develop new skill sets—just as they did when desktop publishing replaced typesetting and manual markup. The pace of change is accelerating, however, so it is increasingly difficult to cram more writing-editing-linking-responding-tweeting-whatever tasks into a single day. The answer, if we are not to be clobbered by technology, is twofold. First, we need to examine what our content teams can do—both as individuals and as a group. Second, we really need to re-examine how we write, what motivates us, and what habits from bygone eras are holding us back.

Web-led, and cloud-based content systems are clearly on the rise, despite the present stopgap of turning print page layout systems into tools for generating native tablet and smartphone apps. Nimble content creation and management tools are still in their infancy, and will improve dramatically over the next five years. However, we cannot afford to forget that content engagement depends on the art of the story, and that great storytellers can thrive in spite of (or hopefully with the aid of) the tools they use. ![]()