For general business use, Content Management Systems (CMS) have become commonplace over the past two decades, lowering IT costs by reducing the need for manual coding. Website-specific CMS (web CMS) emerged approximately during the same period, and for similar reasons. Even with sophisticated HTML editing programs like Dreamweaver, the prospect of manual web page creation was far too costly for large websites—especially those with constantly changing content.

Publishers certainly fall into that category, and their websites have benefited greatly from the editing, syndication, and management features—not to mention the overall cost savings—of web CMS like WordPress, Joomla, and Drupal. For larger publishing operations (and budgets), web CMS can also improve their ability to plan content assignments, collaborate from remote locations, and automate vital functions like search engine optimization (SEO) and social sharing.

The Digital Divide

For any discussion of web CMS, it’s important to understand the differences between traditional and pure-play digital publishers, the latter having no financial reliance on print-based circulation or advertising. According to former Time Inc. executive Peter Meirs of Digital First Media NY, a publisher’s print legacy—or lack thereof—has an impact on its web CMS footprint. “One key difference between natively digital publishers versus a cross platform publishing model is the overhead required for a workflow that includes print or fixed layout design,” he says. “Without these requirements, the CMS does not need to provide as much content transformation and management functionality for text and images. Further, the management of digital assets can be simpler, because the design requirements for web and mobile are less complex.”

Pure play digital publishers still have significant challenges, however. “With pure-play digital (or digital-first) there will not be any print-originated content,” Meirs says, “so the CMS will need to have a robust content creation and editing interface that can manage the assignment of metadata and prepare content for web, mobile, web-app tablets and video players, as well as for social, content marketing and native advertising channels.”

Although traditional publishers are increasingly using the technology, we found that pure-play digital publishers are perceived as web CMS innovation leaders. The New York Times’ media columnist David Carr, in his recent review of the blogging platform Medium, says that “the content management system is destiny,” alluding to Ezra Kline’s recent decision to move from The Washington Post to Vox Media, in part because of the latter’s web CMS.

The Goals of Web CMS

A publisher’s definition of the “ideal” web CMS is based on complicated and often conflicting needs. Some writers (notably experienced bloggers) expect, and are comfortable with, the ability to manage multiple aspects of a story, including revision management, selection and placement of photos and multimedia elements, and even SEO. Others, especially those employed by larger or more complex organizations, need a streamlined means of doing a few tasks well. Writers want to write effectively; editors want to edit, budget, and plan. Photographers and videographers (and their respective editors) want to do their own jobs well, and not be distracted by others. The needs of modern web CMS mirror those of print publishing following the desktop publishing phenomenon of the 1980s. Just because many publishing functions can be done by a single person doesn’t mean that it makes business sense to do so.

Above all, tasks that can be automated in web CMS, like rendering content to multiple platforms or collecting data on usage, should impose as little as possible on those who create and edit content.

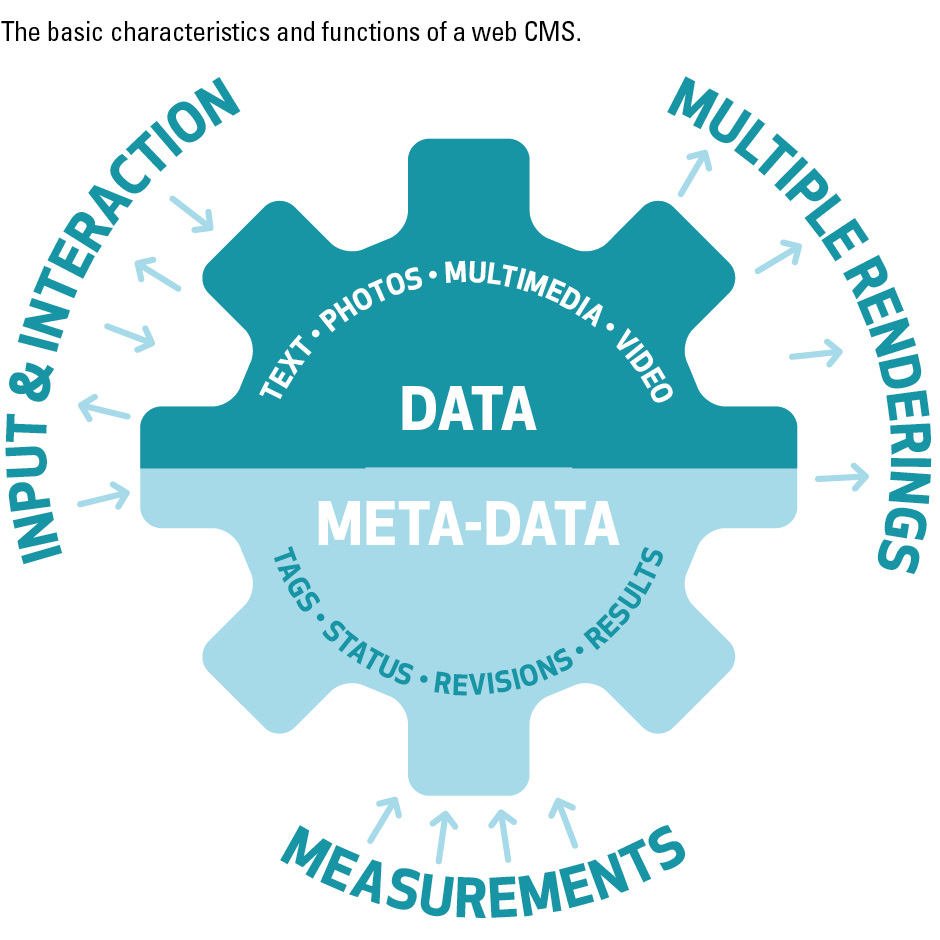

The basic aspects of web CMS are content authoring/editing, the creation and use of various metadata (from element tagging to scheduling and analytics), and content rendering to various digital and even print channels).

Each output channel imposes its own burdens on web CMS and indirectly on the content authors and editors who use it. As digital devices, screen sizes, native apps, browsers, and device capabilities proliferate, the automation of content presentation (HTML5/CSS3) and intelligent tagging will become even more important—allowing content creators to focus on their primary jobs.

For the purpose of this article, the distinction between editorial and advertising content is immaterial to the function of web CMS. Most pure-play digital publishers tend to intermix the two—to the chagrin of many traditional magazine publishers. However, digital-only publishers often clearly label sponsored or advertising content as such, and employ separate teams for editorial and advertising content creation. Controversy over “native advertising” aside, however, there is very little difference from a technology or workflow standpoint between the managed content of editorial and advertising material.

Say It Loud

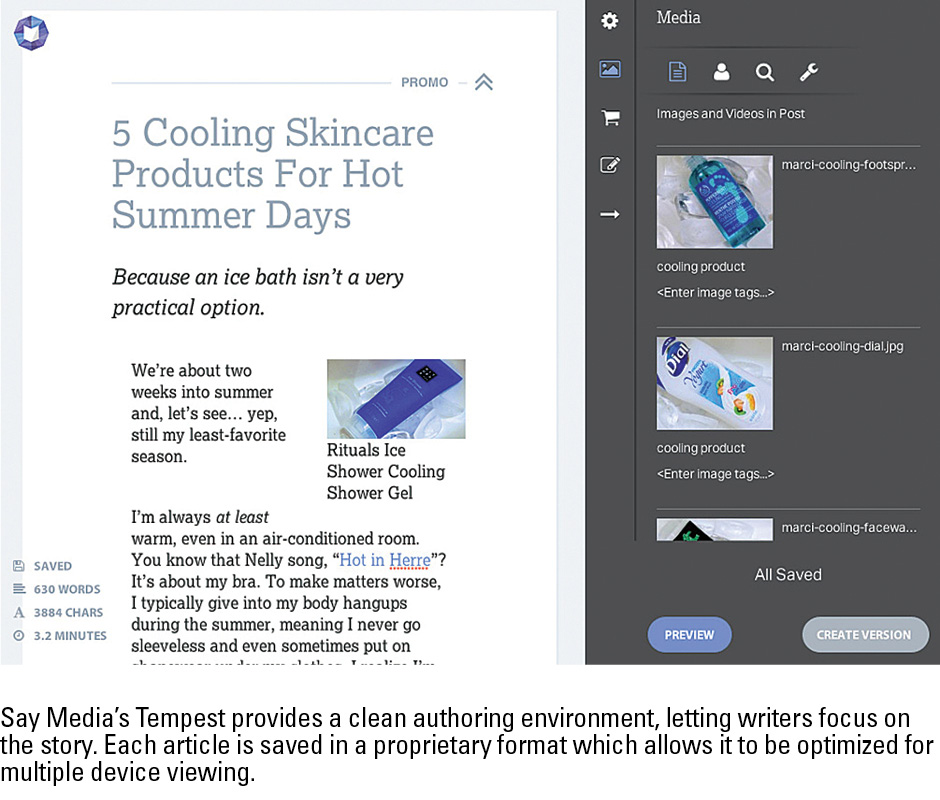

For this article, we interviewed three well-known pure-play digital publishers. According to CTO David Lerman, Say Media has a long history with web CMS. In 2010, it acquired SixApart, the developer of Moveable Type (2001) and TypePad (2003). After the acquisition, it developed a proprietary CMS called Orion. In 2013, the company launched a completely redesigned web CMS, Tempest, which currently powers the majority of the company’s sites. The system was designed to support a largely mobile readership with high quality editorial design, more efficient media handling, and effective monetization. Lerman also notes that Tempest was built to leverage big data analyses, and to increase audiences via search, social networking, and syndication.

Tempest was created to overcome what Say Media perceived as shortcomings with other web CMS approaches. “We wanted to break the cycle of huge redesigns every 1-2 years, and instead optimize for continuous small improvements,” Lerman says. “With Tempest, we’re able to roll out updates to all of our sites on a daily basis, allowing us to constantly test and iterate.” He also stressed that flexible content and layout were important to their growing mobile audience, and that monetization had to be more effective. “Instead of just tacking on standard format ads as an afterthought, Tempest integrates custom marketing solutions that actually work for readers, editors and marketers,” he notes.

Lerman is cautious with regard to open source CMS approaches such as Drupal and Joomla. “We’re big open source fans at Say Media,” he says. “Tempest is built on a number of open source projects including Angular, Node, Sass, and Bourbon. That says, in periods of rapid market change and technology innovation, big open-source projects can be slow to keep up. The new requirements of mobile, social, community, native advertising, and audience development, demand bold moves and rapid innovation. This can be easier to accomplish with a smaller team and a proprietary codebase.”

Although he did not elaborate on the inner workings of Tempest, Lerman did identify one of the primary challenges to any web CMS: mobile publishing. “Mobile requires a more flexible approach to storytelling and design. In the print world, a designer carefully lays out each article, but when that same content could appear on anything from a tiny mobile screen to a cinema display, beautiful layout becomes a significant technology challenge.”

On the subject of mobile monetization, he observes that screen real estate issues are forcing publishers, and their web CMS, to support “better ad products that serve the reader experience while allowing publishers to continue making money.”

Say Media is cultivating partnerships with traditional publishers, who in turn will use the proprietary Tempest system to meet their own goals. “Traditional publishers will have to use web CMS to survive as more of their readers come to them from digital channels,” he says. “Traditional publishers have all the same challenges as pure-play digital, plus the added demands of translating their content between digital and print while managing both businesses.”

Lerman believes that traditional publishers who do not find such partners will need to build out their own technology teams and become hybrid technology/media companies themselves.

What’s the Buzz?

News and entertainment website BuzzFeed started as a technology company in 2006, building its own platform and CMS from the beginning, according to Chris Johanesen, the company’s product vice president. “It has slowly evolved over the years to keep pace with changes in BuzzFeed’s editorial model,” he says. “We started with pure aggregation—linking out to blogs. As time progressed and our editorial direction changed; we added images, videos, lists, text articles, and now, even more advanced formats like quizzes, games, and immersive long-form experiences.”

Johanesen’s criticism of typical web CMS is twofold: “First, they are written very specifically for the desktop web,” he says, “and it is hard for publishers to adapt them to new emergent platforms. Second, it is hard for publishers to experiment with new formats and content types. The primary advantage of having written our own custom CMS is that we can better adapt to those changes on the fly as the internet and our audience changes and grows.” He also feels that publishers should prefer developing their own, open source solutions, as opposed to using someone else’s off-the-shelf system, since they are easier to modify later. “Regardless, it’s important to have good developers, designers, and product people to work with your CMS—the same way print publishers need people who understand paper, ink, and printing presses.”

Mobile is the highest priority in the company’s web CMS strategy, with over 50 percent of its 130 million audience accessing BuzzFeed on a mobile device. Johanesen notes that their CMS was recently updated to include a mobile preview feature, enabling editors why typically work from a desktop computer to view their post as a mobile user would see it—to ensure that all images and videos are working properly. “That says, there are definitely opportunities for mobile content creation that we haven’t tapped into yet, especially in the realm of breaking news and events.”

Johanesen believes that there are more benefits to he had from the ongoing evolution of web CMS. “Consumers will benefit when editors are writing for them, and not for some hypothetical print audience,” he says. “Publications have to make sure they are looking at the right set of metrics and don’t get fixated on page views or time-on-site. Advertisers will benefit if they stop thinking in terms of banner ads and start thinking about how brands can make things that humans actually want to see, share, and interact with.”

Vox Populi

Trei Brundrett is the chief product officer at Vox Media, heading a team of 60 engineers, designers, and managers. The company’s platform, Chorus, was begun seven years ago, and now drives the company’s seven brand websites, the Vox advertising and publishing platforms, and various other technology-driven products. “Vox Media is a company founded by bloggers and we have a strong technology culture,” he says. “We worked closely with these web-native writers and community builders and tried to take a fresh, user-centric approach to the opportunities we saw to change media with technology and design. Part of that meant that we stopped calling it a CMS which sounds like the IT department designs and builds your tools and experiences.”

Brundrett sees many shortcomings in today’s web CMS. They are too focused on managing content, per se, rather than using the medium to cover news, tell stories, build communities of interest, and deliver user-relevant advertising. “Authoring and publishing is at the core of our platform, but thinking of this as a CMS problem is limiting. Our technology is our business.”

He also feels that too many web CMS architects are obsessed with the abstraction of presentation from content. “That assumes writers don’t care where, how, or when their stories are published and displayed. Our writers and editors are obsessed with the entire product and process, so we empower them to have more control, more capabilities and to understand how their audience is interacting with what they produce through community and data.”

For companies that are just getting started with web CMS, or who have limited budgets or must work with legacy systems, open source plays an important role, according to Brundrett. Vox built their proprietary system because they had a broader set of problems to solve, saw the opportunity to create a unique experience for writers and communities, and had to move quickly.

For publishers and advertisers, Brundrett believes that “the ideal platform will be one that allows media companies to act like technology companies—easy to ship new product, easy to iterate on ideas, powerful in the hands of editorial teams who are native to the web and successful for brand advertisers looking to reach engaged audiences.”

Back to the Future?

As proprietary and open source-based systems evolve, the web CMS universe may be poised to become even more mainstream for publishers. According to AdExchanger, Google is developing a CMS that would unify editorial, advertising, and possibly commerce activities for media companies. While pure-play digital companies may continue to outpace Google’s eventual offering, the news is a sign that mainstream publishers—or less affluent ones—are ready for a digital-first approach to content. ![]()

John Parsons (john@intuideas.com) is the principal of IntuIdeas LLC in Seattle. He writes and advises on a variety of topics and technologies, including mobile publishing, online video, editorial and design workflow, e-books, digital color, and web-to-print.