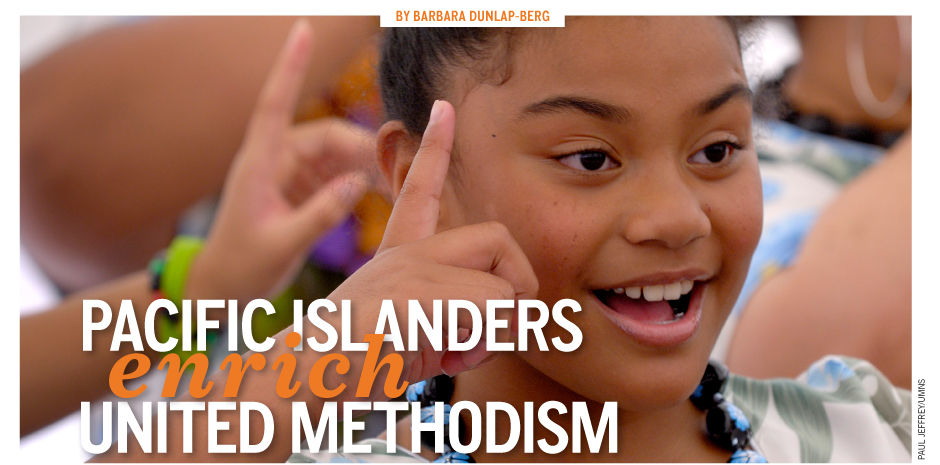

A youth choir member from First Tongan United Methodist Church in Waimanalo, Hawaii, sings during an immigrant rights rally during the 2008 General Conference in Fort Worth, Texas.

A youth choir member from First Tongan United Methodist Church in Waimanalo, Hawaii, sings during an immigrant rights rally during the 2008 General Conference in Fort Worth, Texas.

A youth choir member from First Tongan United Methodist Church in Waimanalo, Hawaii, sings during an immigrant rights rally during the 2008 General Conference in Fort Worth, Texas.

Monalisa Tui’tahi, an immigration attorney, speaks at an 2008 press conference hosted by the United Methodist Task Force on Immigration.

MAILE BRADFIELD/UMNS

PACIFIC ISLANDER UNITED METHODIST TIME LINE

- 1822 – The Methodist Church of Australia sends its first missionaries to Tonga.

- 1893 – Hawaiian Islands become a part of the United States. Although Hawaii is part of the California-Pacific Annual Conference, there is no known native Hawaiian ministry.

- Early 1950s – American Samoa becomes a territory of the United States.

- 1960s – Immigration to the U.S. from Samoa surges.

- 1963 – The first Samoan congregation is established in Honolulu.

- 1970 – The first Tongan United Methodist fellowship is organized in Hawaii.

Methodist immigrants from Fiji have also established ministries in several western states.

The establishment of ministries within these Pacific Island groups coincides with their migration to the United States. Samoan leaders began the work of introducing Pacific Islanders into the denomination. “Unfortunately,” says Monalisa Tui’tahi, a member of the Pacific Islander National Caucus of United Methodists, “growth in the Samoan United Methodist community has dwindled with the loss of charismatic first-generation leaders.”

According to 2010 data from the Pacific Island Ministry Plan, 81 Pacific Islander United Methodist churches are spread over seven conferences – Alaska United Methodist, California-Pacific, California-Nevada, Central Texas, Desert Southwest, Oregon-Idaho, Pacific Northwest and Rocky Mountain. Tongans have the largest percentage of congregations (72 percent). There are also Samoan (15 percent), Fijian (11 percent) and a Chamorro (Marianas Islands) congregation based in Guam. Most of the congregations are fellowships or ministries; only a few are chartered. Congregants typically worship in their native language.

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. Delegates to the 2012 United Methodist General Conference approved a comprehensive plan for ministry with Pacific Islanders in the United States. The plan seeks to empower United Methodists of Pacific-Islander heritage to participate fully in the life of the denomination, navigate their faith life, bring diverse gifts to the table and affirm the common heritage of Pacific-Island people.

Here Monalisa Tui’tahi, an attorney in California and a member of the Pacific Islander National Caucus of United Methodists, shares her story.

“My family emigrated [from Tonga] to Hawaii in the mid-1970s,” said Tui’tahi. Her parents and 14 siblings became part of the Tonga congregation at Kahuku United Methodist, a small country church on the north shore of Oahu, Hawaii. Its multiethnic membership reflected the early plantation population of the Hawaiian island and included a sprinkling of mainland transplants.

“In their wisdom,” Tui’tahi said, “the church leadership understood the immigrants’ need to practice their faith in the way they were accustomed to in their native island. Their faith experience and church community lessened the sense of social and cultural disorientation naturally experienced by immigrants.

“My father made sure we attended the Tongan Sunday school and services, sang in the Tongan choir and attended the Tongan youth programs,” she continued, “but he also allowed us to take part in the church youth group and the youth choir and attend the English worship services. The experience provided a great forum for cross-cultural learning and certainly helped in the assimilation process.”

Tonga, about 3,000 miles from Oahu, is a Christian nation, with more than a third of the population adhering to the Methodist tradition. “Although The United Methodist Church is not in Tonga,” Tui’tahi noted, “Tongan immigrants seek out Methodist-affiliated denominations, and hence, The United Methodist Church is a natural fit.”

Today, Tui’tahi is a member of the Tongan fellowship of Santa Ana United Methodist Church in California. Her husband, the Rev. Siosaia Tui’tahi, serves First United Methodist Church, Santa Ana.

One of five language fellowships (English, Cambodian, Filipino/Tagalog, Spanish and Tongan) at the Santa Ana church, the Tongan congregation is primarily first-generation Tongans with a few non-Tongan spouses. “About 125 strong,” Tui’tahi said, “its primary ministry ... is to provide spiritual formation and to promote spiritual disciplinary practice within the life of its members. The fellowship becomes a bridge for cross-cultural interaction and learning, as at least four different ethnic groups live into the reality of being one church.

“This is enriching yet challenging,” she added. “Like other Pacific Island congregations, the members live out a communal charge to help each other in all things. Hence, the fellowship becomes a tool for learning and better understanding of services and information useful for first-generation immigrants.”

An ‘abundance of young people’

A major focus is the second generation and the young people, who participate in camps, college-planning seminars, mission service projects, community outreach and programs to maintain Tongan language, tradition and culture.

“One of the gifts of the Tongan churches is the abundance of its young people,” Tui’tahi said. “‘They are in the pews; they are in church. This is, perhaps, tied to a strong value of obedience within the Tongan family structure. Young people are taught to understand their faith within the Tongan context and to practice that faith. The Tongan churches are also doing well in keeping the Tongan culture alive for their young people.”

Tongan young people struggle with many of the same issues that confront other immigrant families – gang violence and reluctance to pursue higher education. Perhaps because of “the close-knit community setting, the smallness of the island in geography and life experience, Tongan young people remain close to home,” she said.

Tongan churches, Tui’tahi said, need to respond to this reality by creating space for young people in the church that “will allow them to grow [and] to feel that they are relevant to the life of the church.”

Tui’tahi pointed to progress since General Conference 2012 approved the Pacific Islander Ministry Plan.

- Approximately 300 Pacific Island United Methodists have participated in leadership-development programs addressing their needs. “This is critical,” she said, “for this primarily first-generation community as their needs are so different and varied from those of the mainstream community.”

- Pacific Islanders have gained visibility as annual conferences become more aware of their presence. “The plan provides needed resources for development of Pacific Island ministries across the connection,” Tui’tahi said. Pacific Islanders also have greater access to general agencies, particularly the General Board of Global Ministries, which administers the plan.

- A young people’s task force focuses on developing leaders among young people and second-generation immigrants. The plan is looking at other regions in the United States that have pockets of Pacific Islanders. Plans are underway to plant churches in those areas.

‘A theology of abundance’

Tui’tahi noted that Pacific Islanders have embraced United Methodism fervently and passionately. “Culture and faith come together to form a strong and resilient foundation.”

For Pacific Islanders, a theology of abundance proves vital.

“Pacific Islanders live out their faith consistent with a theology of abundance,” Tui’tahi said. “Ministries are built on the premise that God will provide the means to spread the gospel, and although money is needed, it is not the basis for building ministries. The system of mutuality that undergirds the Pacific Island culture and life plays an important role in ensuring that everyone participates in the work of building the ministry.”

This leads to overflowing hospitality.

“The work of growing churches and effective mission and evangelization must be based on building effective relationships,” Tui’tahi added. “Within the Pacific Islanders’ communal context, relationships are valued, and everyone is affirmed, and hence worthy of hospitality. As often is the case, when the end is affirmed and celebrated, the means always follow.”

She stressed the importance of recognizing the contributions of all United Methodists and building learning bridges for “authentic sharing of gifts and resources.”

“Two-way learning opportunities must be made available for clergy, lay, youth and young people. The far and wide countries of the world that were once mission fields are now in the pews and are a living part of the church in the U.S.”

Barbara Dunlap-Berg is associate editor of Interpreter and Interpreter OnLine,www.interpretermagazine.org.