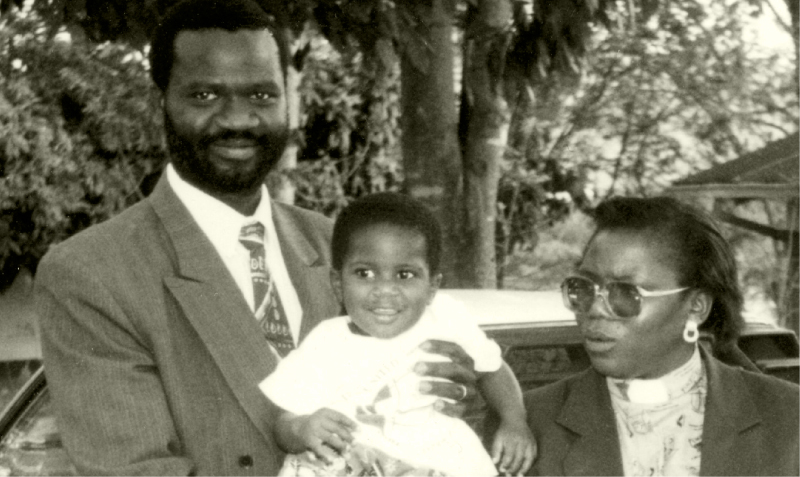

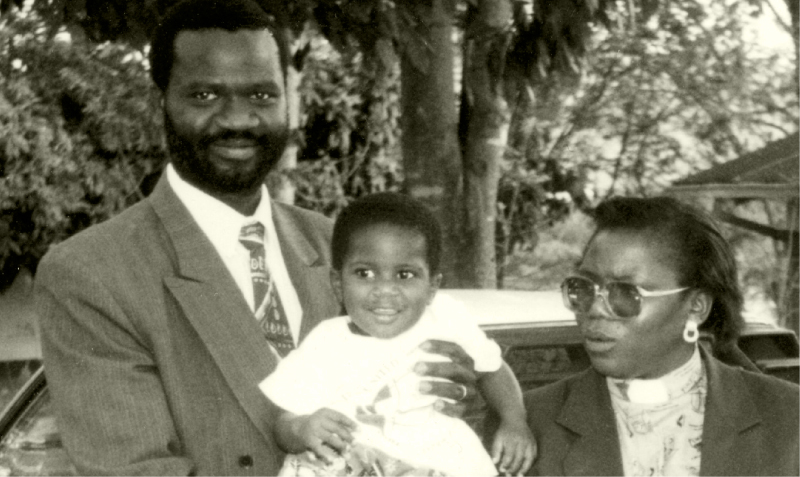

Tafadzwa (left) and the Rev. Ever Mudambanuki pose with their toddler son, Wesley.

COURTESY PHOTO

Tafadzwa (left) and the Rev. Ever Mudambanuki pose with their toddler son, Wesley.

COURTESY PHOTO

In August 1998, I arrived in Dayton, Ohio, from Zimbabwe to pursue a graduate degree in religious communication. The only way to communicate with my Mutare-based family was with frequent phone calls. After a Thanksgiving lunch, I placed a call to my family. I received dreaded news that our son, Wesley, had fallen ill to a mysterious illness. His body temperature was bread-oven hot from head to waist and the fever alternated between there and his waist to his toes for 10 days. Wesley was our first child. Hearing that he had contracted a mysterious illness devastated me.

On Dec. 4, 1998, Community United Methodist Church in Brookville, near Dayton, bought a ticket for me to go and bring Wesley to the United States for medical treatment. I arrived in Zimbabwe mid-morning Dec. 5, and Bishop Christopher Jokomo and Dr. Bill Humbane and his wife, Maria, were at hand to receive me at the Harare airport.

Whisking me away from the crowd as soon as I claimed my luggage, they surrounded me and held my hands. Through prayer, Bishop Jokomo delivered to me the news of Wesley’s death. I stumbled – breaking the wall of hands they had formed to prevent me from falling. There was a thud as I fell and wailed loudly on the Harare airport tarmac.

The death of Wesley was wrenching, unexpected and incomprehensible. Children are supposed to live longer than their parents do. When they do not, the pain is unimaginable. I sobbed the entire three-and-a-half-hour drive from Harare to Mutare. I thought life was not worth living because of the intense pain I endured from losing Wesley.

As soon as I arrived at the Hilltop United Methodist Church parsonage where we lived, people started wailing, the Zimbabwean custom for paying last respects. We mourned together. Family members and friends accompanied me to the morgue to collect Wesley’s body for an overnight vigil.

The thought of living my life without Wesley was frightening. I began re-examining priorities and questioning belief structures. People poured into the parsonage and the memorial service to offer their condolences.

Although well-meaning and attempting to console us, many pastors said words that were unhelpful to my wife, the Rev. Ever Mudambanuki, and me when we lost Wesley. Here is some of what we heard during our son’s funeral:

“It is all part of God’s plan; just accept it as believers.”

“God wanted another flower in his garden; please be comforted Wesley is in a better place.”

“I know exactly how you feel.”

“You can have other children.”

“Put this behind you for God has another plan for you.”

“You have to get on with your life.”

“Wesley was not yours to send to the grocer’s store.”

“God gave you and so God has taken Wesley back.”

As the church community tried to comfort us, some even said, “Since you are preachers, God is preparing you to be more empathetic to others.”

‘Cry hard when you feel like crying’

One pastor said, “You need counseling to get over this.”

I thought to myself, “Why counseling? Can this bring back my Wesley?” I did not feel right about counseling, but those Goliath-like voices were so insistent on counseling that I almost accepted it. At times, we felt like a pariah couple. We did not have other children, so that made the grief harder. “Look at the man who just lost a child,” said some sympathizers. I felt a lump on my throat, and tears welled up in my eyes.

I realized that we, as Christians, are not taught how to deal with death and what to say. I sincerely think people are not callous and unfeeling when they say unintentionally hurtful words when death occurs. People have no clue of what to say when a tragedy happens.

Those who had lost children made empathetic – and helpful – comments.

The Revs. Forbes and Nyaradzai Matonga checked on us daily by phone and made frequent visits to our home.

“My fellow brother, cry hard when you feel like crying,” Forbes said. “This is what helped me grieve when we lost our baby.” Wesley was a healthy boy, and this sudden death made it hard to accept that his life was cut short. “There was so much unfilled potential still ahead of him,” he said.

The most painful part was when all family members, relatives and friends went home, and we could only stare at an empty cot in our bedroom. The death of a child interrupts the natural order of life. Ever and I had reached rock bottom – the lowest place we could go. And, yet, we found out that we could stand on Jesus Christ, the Rock that never fails. With a firm belief in Jesus, we started to climb out of the abyss of grief.

I grieved intuitively and took solace in sharing pleasant memories of my son. I arrived back in Ohio a month later. Wanting to do something constructive, some bereaved couples established a garden of flowers in his memory.

Wesley’s death forced us to find a new normal. I had to learn to let go of things I could not control. During my grieving period, I realized when I talked to the Matongas about the death of our son, I felt good, and they could see a palpable look of relief and gratitude over my face as we chatted.

Tafadzwa Mudambanuki is coordinator of central conference content for United Methodist Communications. He, Ever Mudambanuki and their second son, Kingsley, 15, live in Hermitage, Tennessee.