Director's Forum

A Primer on Prescription Drug Abuse and the Role of the Pharmacy Director

Andre Harvin, PharmD, BCPS,* and Robert J. Weber, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FASHP†

Director's Forum

A Primer on Prescription Drug Abuse and the Role of the Pharmacy Director

Andre Harvin, PharmD, BCPS,* and Robert J. Weber, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FASHP†

Director's Forum

A Primer on Prescription Drug Abuse and the Role of the Pharmacy Director

Andre Harvin, PharmD, BCPS,* and Robert J. Weber, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FASHP†

Prescription drug abuse, or using a prescription drug in a way not intended by the provider, has become such an issue in the United States that in 2013 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified it as a new epidemic. The goal of this article is to provide pharmacy directors with a primer on prescription drug abuse and its prevention. This article will cover the causes and societal impact of prescription drug abuse, review recent and proposed strategies to prevent prescription drug abuse, and discuss efforts within the health system to reduce the risks of narcotic diversion that can lead to prescription drug abuse. There are several health and societal factors that have contributed to the rise in prescription drug abuse. As there is no singular contributory factor to this epidemic, there is no easy solution for proper containment and monitoring of prescription drug use. Pharmacy directors play a vital role in the safe use of prescription medications by providing for fail-safe systems for accounting and controlling prescription drugs. In addition, pharmacists can play a role in educating patients and health care workers on the dangers of prescription drug abuse. Health systems should form teams to identify drug diversion and provide an intervention that demands accountability while helping the impaired professional. Health system pharmacy directors must play an integral role in these efforts and continue to seek opportunities to reduce any risks for prescription drug abuse.

Prescription drug abuse, or using a prescription drug in a way not intended by the provider, has become such an issue in the United States that in 2013 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified it as a new epidemic. The goal of this article is to provide pharmacy directors with a primer on prescription drug abuse and its prevention. This article will cover the causes and societal impact of prescription drug abuse, review recent and proposed strategies to prevent prescription drug abuse, and discuss efforts within the health system to reduce the risks of narcotic diversion that can lead to prescription drug abuse. There are several health and societal factors that have contributed to the rise in prescription drug abuse. As there is no singular contributory factor to this epidemic, there is no easy solution for proper containment and monitoring of prescription drug use. Pharmacy directors play a vital role in the safe use of prescription medications by providing for fail-safe systems for accounting and controlling prescription drugs. In addition, pharmacists can play a role in educating patients and health care workers on the dangers of prescription drug abuse. Health systems should form teams to identify drug diversion and provide an intervention that demands accountability while helping the impaired professional. Health system pharmacy directors must play an integral role in these efforts and continue to seek opportunities to reduce any risks for prescription drug abuse.

Prescription drug abuse, or using a prescription drug in a way not intended by the provider, has become such an issue in the United States that in 2013 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified it as a new epidemic. The goal of this article is to provide pharmacy directors with a primer on prescription drug abuse and its prevention. This article will cover the causes and societal impact of prescription drug abuse, review recent and proposed strategies to prevent prescription drug abuse, and discuss efforts within the health system to reduce the risks of narcotic diversion that can lead to prescription drug abuse. There are several health and societal factors that have contributed to the rise in prescription drug abuse. As there is no singular contributory factor to this epidemic, there is no easy solution for proper containment and monitoring of prescription drug use. Pharmacy directors play a vital role in the safe use of prescription medications by providing for fail-safe systems for accounting and controlling prescription drugs. In addition, pharmacists can play a role in educating patients and health care workers on the dangers of prescription drug abuse. Health systems should form teams to identify drug diversion and provide an intervention that demands accountability while helping the impaired professional. Health system pharmacy directors must play an integral role in these efforts and continue to seek opportunities to reduce any risks for prescription drug abuse.

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(5):423–428

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5005-423

Prescription drug abuse, or using a prescription drug in a way not intended by the provider, has become such an issue in the United States that in 2013 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified it as a new epidemic.1 Prescription drug abuse is referred to as “the silent epidemic,” because most people are unaware that it causes deaths due to overdose and improper use. Prescription drug overdoses surpassed motor vehicle accidents as the leading cause of injury-related deaths in 2009.1,2 State and federal agencies have dedicated efforts to increase awareness and enact strict rules and regulations about the use of drugs with the potential for abuse, most notably opioids. These programs have been marginally successful, but they have not slowed the increase in deaths related to prescription drug abuse.

Hospitals and health systems play a crucial role in preventing prescription drug abuse. Health system pharmacies, in particular, can provide education about and specific controls over the use of prescription drugs. The goal of this article is to provide pharmacy directors with a primer on prescription drug abuse and its prevention. This article will cover the causes and societal impact of prescription drug abuse, review recent and proposed strategies to prevent prescription drug abuse, and discuss efforts within the health system to reduce the risks of narcotic diversion that can lead to prescription drug abuse.

IMPACT OF PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE

Deaths Associated with Prescription Drug Abuse

Compared to other leading causes of death in the United States, prescription drug abuse has grown exponentially over the last decade. The death rates for prescription drug overdose have increased more than 5-fold within the last 30 years, with a startling upturn of deaths in the last decade. A 2011 national survey conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse found that over 52 million Americans admitted to either the misuse or abuse of a prescription medication at some point in their lives. Furthermore, the survey noted that nearly 14 million Americans were current nonmedical users of prescription medications.3

Most prescription drugs abuse cases involve opioids. In 2010, prescription opioids were involved in the deaths of over 16,000 Americans. To put this into perspective, prescription opioids far exceeded the combined deaths attributed to illegal and illicit drugs (eg, heroin, cocaine, and phencyclidine). Benzodiazepines, the medications involved with second highest number of deaths, also exceeded the number of deaths from all illicit drugs combined. Medications obtained by legal means of a prescription and taken in an abusive manner are equally or more dangerous than illicit or illegal drugs.

Cost of Prescription Drug Abuse

Prescription drug abuse has a significant financial impact. A study examining prescription drug abuse from 2004 to 20111 showed that emergency department (ED) visits associated with prescription drug abuse increased by 114%. Medications associated with prescription drug abuse ED visits increased by the following: oxycodone-containing products, 242%; alprazolam, 148%; and hydrocodone-containing products, 124%. The direct medical costs of prescription drug abuse are estimated to be over $72 billion each year. This estimate includes the costs of acute clinical management, lost work productivity, criminal justice procedures, and outpatient treatment centers. Opioid drug abuse costs insurers on average $14,000 more annually per patient compared to patients without prescription drug abuse issues.4

UNDERSTANDING PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE

Risk Factors

Prescription drug abuse is twice as prevalent in women. A recent report conducted by the CDC noted that women were prescribed drugs with abuse potential more often than men.2 Over the past decade, the percentage increase for prescription drug overdose resulting in death was significantly greater among women (400%) compared to men (265%). The rates of nonmedical use of prescription medications by age group are comparable to the distribution of illicit drug use among age groups, with the highest use in persons 18 to 25 years old, followed by 26 to 34 years old, and then 35 to 49 years old.1 Although the younger age groups are more likely to abuse prescription medications, the older age groups (35-49 years old and ≥50 years old) demonstrate the greatest increase in abuse and misuse over the past decade. Rates of abuse are projected to be almost equal across the identified age groups by the end of the next decade.

The distribution by race and ethnicity varies dramatically. American Indians/Alaska Natives and Whites have rates of abuse and misuse that far exceed the next closest ethnic group.1 Whites are nearly twice as likely as other ethnic groups to visit the ED for prescription medication overdoses and are the single largest consumers of outpatient treatment resources. Medicaid patients make up the highest volume of prescription medication abusers, however recent trends indicate that the gap is closing when compared to patients who are self-insured or have third-party insurance. Persons at risk of prescription drug abuse are more likely to have a history of chronic pain; orthopedic surgery, trauma, and cancer pain are common etiologic factors. Persons with mental health disorders and past histories of substance abuse problems, either illicit or prescription drugs, are also at increased risk for abuse and overdose.

Prescribing Patterns and Prescription Drug Abuse

There is a direct linear relationship between the increase in opioid prescribing and the rise in opioid-related morbidity and mortality. Prescribers have increased the number of unique opioid prescriptions, the number of tablets prescribed per prescription, the days’ supply, and the cumulative dose of prescription opioids over the last decade. Since 1991, the total number of opioid prescriptions dispensed has increased each year, with only the most recent data showing a leveling of dispensing patterns. The greatest growth in prescribing trends is primarily seen in chronic non-cancer pain, as cancer pain prescribing has remained relatively consistent over the last decade.2,5

The documentary, The Oxycontin Express,6,7 detailed the prescribing patterns of physicians located primarily in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Ohio as being some of the highest volume prescribers of prescription narcotics. Florida was the home of the top 5 prescribers of oxycodone and hydrocodone-containing products in the United States. Florida was also the leader in prescription drug overdose mortality and overdose-related expenditures. A study completed in Kentucky in 2009 found that 82% of all controlled substance prescriptions written in that state were attributable to less than 20% of the physicians in the state.6 Similar results were found in Oregon where 4.1% of all prescribers in the state were responsible for just over 60% of all controlled substance prescriptions.7

Logic would lead us to believe that top prescribers of controlled substances specialize in pain medicine. However, as of 2013 there were fewer than 4,800 board-certified pain specialists in the United States, compared to 1,004,635 total active prescribers. These data indicate that chronic non-cancer pain medications are being prescribed at an alarming rate by physicians without specialized knowledge in the area of proper pain management. The overall lack of education and awareness of the safe and effective practice of pain management is a direct contributor to abuse, misuse, and overdose.

Clinical Management of Chronic Pain

An important cause of prescription drug abuse is the effort by physicians and others to effectively manage chronic non-cancer pain. Physicians without specialized knowledge in pain management may consistently undertreat these patients out of fear of prescribing too many medications or prescribing doses that are too high. Patients with mismanaged chronic pain may resort to taking their medications outside of the prescribed guidelines. If prescribers are not adequately prepared to care for these patients, the patients may resort to alternative measures for acquiring the prescription medications. Undertreatment is a risk factor for abuse and overdose. Conversely, prescribers who overtreat pain, either intentionally or unintentionally, put more people at risk than just the patients they are treating. A 2012 survey conducted by HHS found that 68.9% of prescription opioids were obtained from a friend/relatives prescription supply.1 An exceptionally low percentage of respondents indicated the need to purchase prescription opioids from drug dealers or through online sources, as these drugs were readily accessible through friends and relatives. Physician prescribing habits and lack of clinical knowledge with the treatment of pain are direct drivers for the increased prescriptions of opioids.

The widespread prescribing of opioids contributes to the supply that is available for diversion, unintentional misuse, recreational abuse, and other potential harms. A study conducted by the University of Utah showed a disconnect between expected acute pain durations and days’ supply of prescription opioids.7 A study of 586 patients who underwent an elective urology procedure found that 63% were prescribed at least one opioid product for acute pain management. Of those patients, over half were prescribed a supply of opioids for 10 to 30 days. This is concerning because the recommendation for pain management for these procedures is the use of opioids for 7 to 10 days followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as needed. Among the patients receiving opioids, 67% had leftover medication; over 90% of them received no instructions on how to dispose of the extra tablets. The respondents kept the extra tablets in the house, with 91% indicating they still had the tablets 3 months after they were prescribed.

Pill mills were significant contributors to narcotic oversupply during the mid to late 2000s. A pill mill is a doctor’s office, clinic, or health care facility that routinely conspires in the prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances outside the scope of prevailing standards of medical practice.7 Although Florida was most impacted by the unethical practice of pill mills until recently, similar practices have been described in a number of states. It is difficult to quantify the negative impact of pill mills in the United States; but at the height of their popularity, enough prescription opioids were prescribed and dispensed in a single

year to medicate every American adult around-the-clock for 1 month. Since pill mills were brought to national attention, several state and federal laws have been enacted to combat this immoral prescribing and dispensing practice. The laws will be examined later in this article.

STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTING PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE

Legal and Regulatory Controls

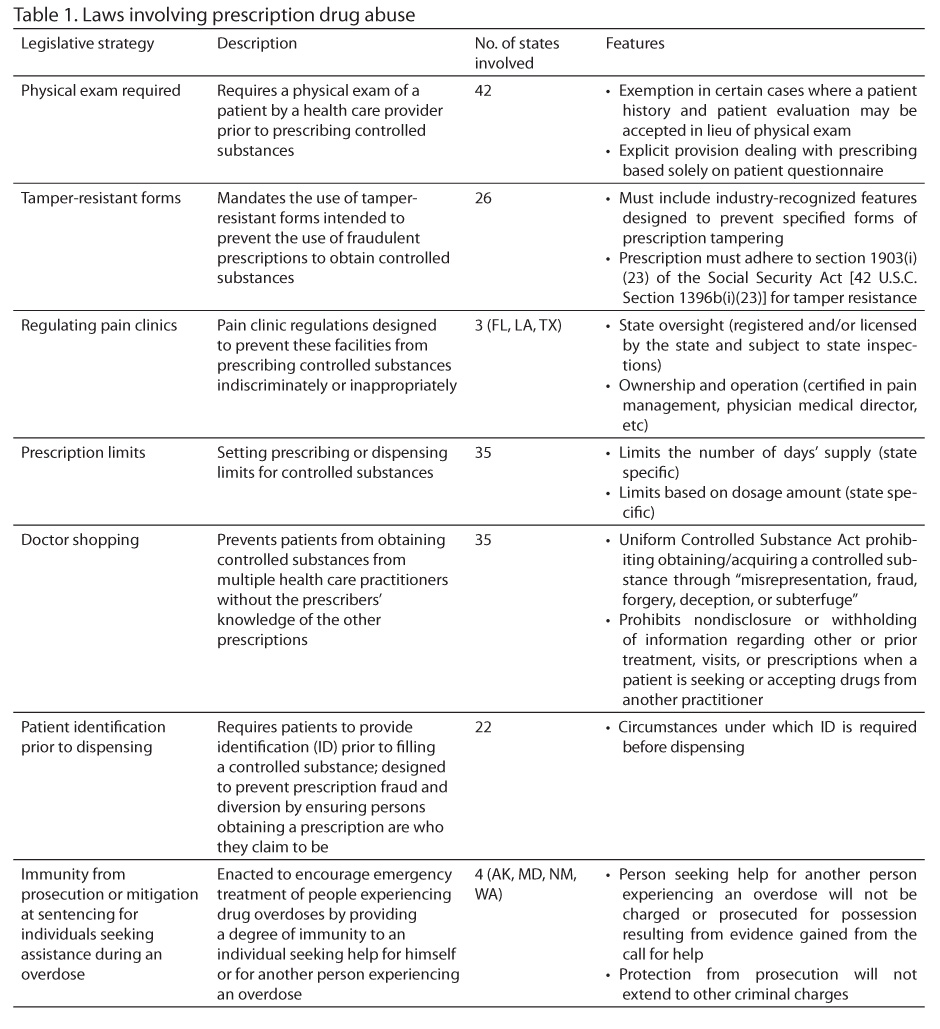

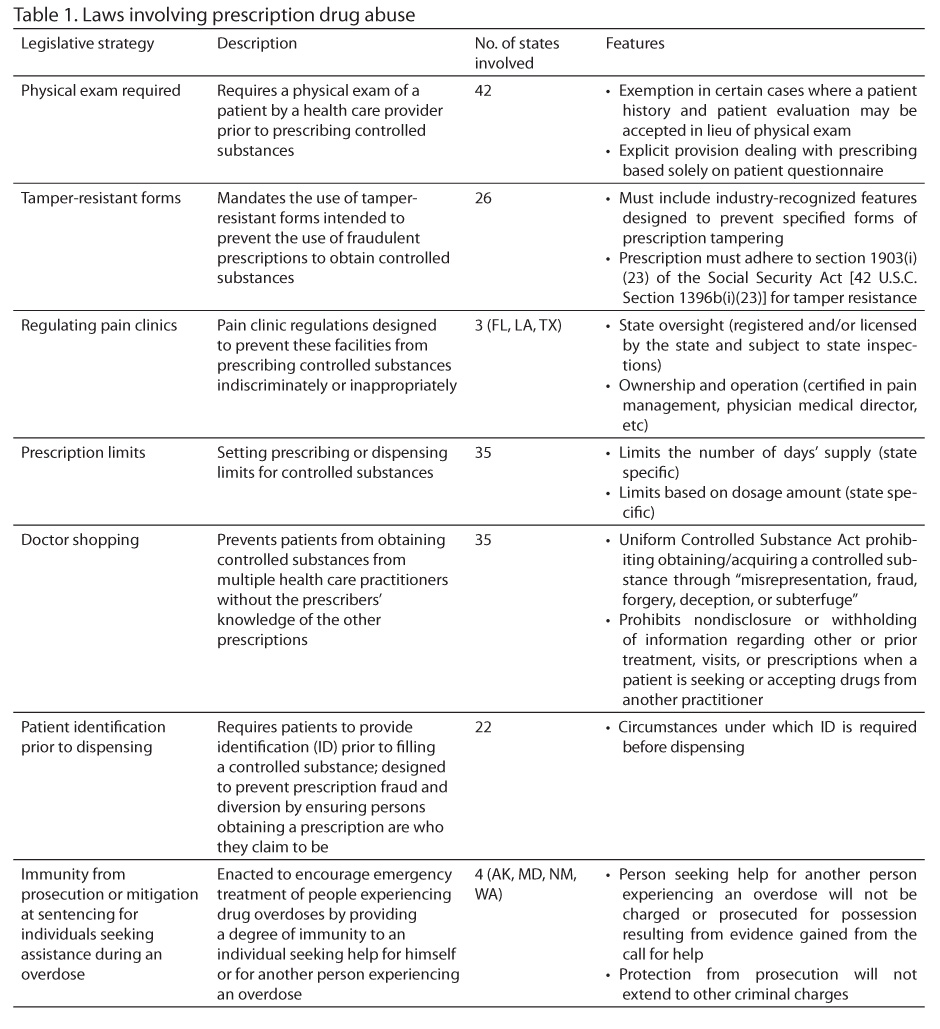

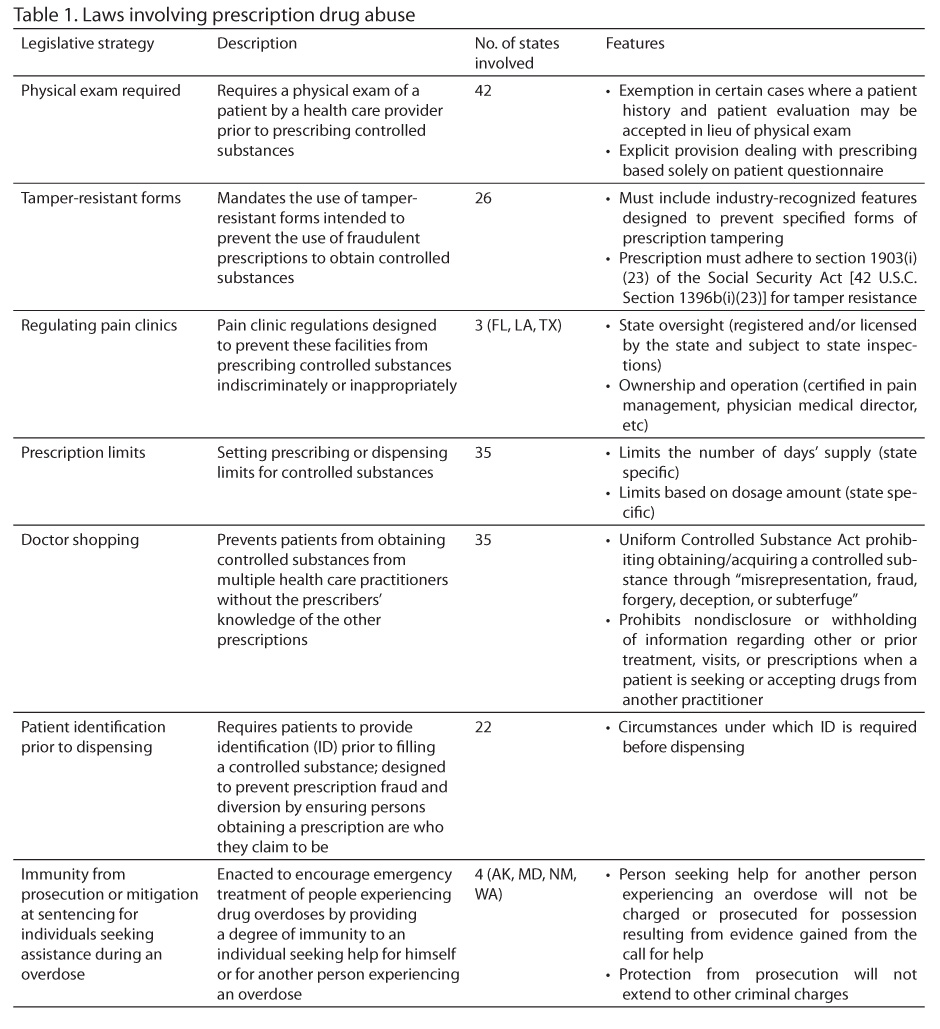

Many states have enacted laws and designed various programs to prevent prescription drug abuse. As of 2010, only 1 state (Montana) had not adopted any laws or monitoring programs, 3 states adopted 1 law, 15 states adopted 2, 19 states adopted 3, 7 states adopted 4, 5 states adopted 5, and 1 state adopted 6 (Florida). A summary of these laws and programs are provided in Table 1. Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are statewide initiatives that utilize electronic database records to collect designated data on prescriptions dispensed in the state. The PDMP data are housed by a specific statewide regulatory, administrative, or law enforcement agency that is directly responsible for the dissemination and security of the information either within the state or within those states with which they collaborate. It is important to note that these programs are state specific and have no oversight from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) or the US Food and Drug Administration. As of January 2014, 46 states have active PDMPs, 3 states have PDMPs that are not operational, and 1 state (Missouri) has no PDMP.8

Although state programs have been effective in curbing prescription drug abuse, problems still exist. There is no consensus on minimum dose equivalent (MEQ) levels among practitioners and pain experts. State MEQ levels range from as low as 60 mg to as high as 150 mg, with little concrete evidence regarding the selection of the levels. This lack of consensus leads to significant disagreements that can persist throughout the medical care team. The American Medical Association (AMA) adopted a particularly scathing view of the pharmacists’ role in prescription drug abuse, misuse, and overdose1,2,6: The AMA challenged the pharmacists’ role in questioning physicians about prescriptions for opioids. Despite this conflict, the AMA continues to engage its membership to advocate for responsible opioid prescribing.

Recent legislation has been intended to reduce the abuse potential of the medications that are commonly cited in overdoses and addiction programs, including the DEA’s final decision to reschedule hydrocodone and hydrocodone-containing products from a schedule III to the stricter schedule II class. This precedes the most recent rescheduling of tramadol from a legend drug to a schedule IV medication. These 2 pieces of legislation divided the pharmacy community. Most notably during the hydrocodone debate, the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) did not support the rescheduling, whereas the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) was in support. Both groups agreed with the need to reduce inappropriate access to hydrocodone-containing products. Community pharmacists were the most impacted group regarding their dispensing and record-keeping practices.

Health System Pharmacy Surveillance Programs

Within the hospital setting, physicians, pharmacists, and nurses are responsible for the management of chronic and acute pain and the safe and efficacious use of prescription opioid products. There are several strategies that can be used in the hospital setting to ensure safe practice management. First, hospital systems should focus on building collaborative teams consisting of physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and social work and risk management staff who have specialized education or training involving pain management. At The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center (OSUWMC), the department of pharmacy employs a pain and palliative medicine clinical specialist pharmacist. The department also supports a postgraduate year 2 pain and palliative medicine residency program in conjunction with The Ohio State University College of Pharmacy. This pharmacist provides consultative and rounding services for inpatient and outpatient clinical services for the management of non-cancer chronic pain.

Pharmacists trained in pain management are in an ideal position to conduct and interpret toxicology screenings for patients on chronic therapy. Toxicology reports can determine whether patients are utilizing illicit drugs or other non-prescribed medications. These pharmacists also provide comprehensive services including medication reconciliation, profile review, discharge counseling, and transitions of care services. Discharge counseling and transitions of care services are among the most important clinical activities that pharmacists can provide for patients suffering from chronic pain.

As previously reported in Hospital Pharmacy,9 OSUWMC uses a Code N process to manage potential narcotic diversion. Code N is a process where a multidisciplinary group investigates possible narcotic diversion cases, upholding the state and federal requirements for the safe use of scheduled prescription medications. The group is charged with the surveillance, investigation, and execution of policies and procedures aimed at mitigating drug diversion. The group is comprised of representatives from risk management, pharmacy, employee health, human resources, security, and nursing and a representative from the area or unit where the individual was identified for the Code N.

Possible cases of drug diversion are identified through various electronic systems that monitor the utilization of controlled substances by health care workers. Individuals who exceed a range of controlled substances dispensed, wasted, or otherwise disposed are identified for further investigation. Data from these cases are reviewed by the Code N team, and a decision is made to confront the individual(s) possibly involved in drug diversion. The intervention includes an interview and required urine drug toxicology testing; the results are then reviewed by a qualified physician and interpreted for the Code N team. The result of this investigation is reported to the appropriate licensing boards. If the urine drug screen is negative, appropriate human resources follow-up addresses practice issues related to narcotic documentation and control.

The Code N process continues to be revised to best meet the needs of the employee with an addiction problem while protecting the welfare of patients and the hospital. The program’s goal is to identify health care workers with addiction problems and provide the necessary intervention based on the circumstances. In 2014, the group designed a process for employees to seek appropriate medical care for addictions while forcing accountability for behavior. The Code N team is able to redirect troubled employees to appropriate treatment options and hopefully return them to a healthy and productive life.

CONCLUSION

Prescription drug abuse continues to be a problem in US health care. There are several health and societal factors that have contributed to rise in prescription drug abuse. As there is no singular contributory factor to this epidemic, there is no easy solution for proper containment and monitoring of prescription drug use. Pharmacy directors play a vital role in the safe use of prescription medications by providing fail-safe systems for accounting and controlling prescription drugs. In addition, pharmacists can play a role in educating patients and health care workers about the dangers of prescription drug abuse. Health systems should form teams to identify drug diversion and provide an intervention that demands accountability while helping the impaired professional. Regardless of the efforts, health system pharmacy directors must play an integral role in these efforts and continue to seek opportunities to reduce any risks for prescription drug abuse.10

REFERENCES

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Author; 2013. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHnationalfindingresults2012/NSDUHnationalfindingresults2012/NSDUHresults2012.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2015.

- Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee, Prescription Drug Abuse Subcommittee. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: Current activities and future opportunities. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; September 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/pdf/HHS_Prescription_Drug_Abuse_Report_09.2013.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2015.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Rockville, MD: Author; 2012. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/Revised2k11NSDUHSummNatFindings/Revised2k11NSDUHSummNatFindings/NSDUHresults2011.htm. Accessed March 30, 2015.

- Paulozzi L, Jones C, Mack K, Rudd R; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: Overdoses of prescription opioid analgesics – United States, 1999 – 2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492.

- Jones, CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;20:309(7):657-659.

- Levi J, Segal LM, Fuchs Miller A. Prescription drug abuse: Strategies to stop the epidemic, 2013. Trust for America’s Health. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2013/rwjf408045

- Kirschner N, Ginsburg J, etc. Prescription drug abuse: Executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):198-200.

- Traynor K. Data-sharing project seeks to cut drug abuse, diversion. Am J Hosp Pharm. 2012;69(15): 1274,1276-1277.

- Siegel J, O’Neal B. Code N: The intervention process. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(7):653-656.

- Dove B. American Academy of Pain Medicine comments on rescheduling hydrocodone: Patient and public health considerations. A position statement from the American Academy of Pain Management. 2014. http://www.painmed.org/files/hydrocodone-patient-and-public-health-considerations.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2015.

*Senior Pharmacy Resident, †Administrator, Pharmacy Services, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and College of Pharmacy, Columbus, Ohio