Director's Forum

Managing Conflict: A Guide for the Pharmacy Manager

Ryan J. Haumschild, PharmD, MBA*; John B. Hertig, PharmD, MS†; and Robert J. Weber, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FASHP‡

Director's Forum

Managing Conflict: A Guide for the Pharmacy Manager

Ryan J. Haumschild, PharmD, MBA*; John B. Hertig, PharmD, MS†; and Robert J. Weber, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FASHP‡

Director's Forum

Managing Conflict: A Guide for the Pharmacy Manager

Ryan J. Haumschild, PharmD, MBA*; John B. Hertig, PharmD, MS†; and Robert J. Weber, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FASHP‡

Managing conflict among a variety of people and groups is a necessary part of creating a high performance pharmacy department. As new pharmacy managers enter the workforce, much of their success depends on how they manage conflict. The goal of this article is to provide a guide for the pharmacy director on conflict in the workplace. By evaluating each type of conflict, we can learn how to respond when it occurs. Resolving conflict requires a unique and individualized approach, and the strategy used may often be based on the situational context and the personality of the employee or manager. The more that pharmacy leaders can engage in conflict resolution with employees and external leaders, the more proactive they can be in achieving positive results. If pharmacy directors understand the source of conflicts and use management strategies to resolve them, they will ensure that conflicts result in a more effective patient-centered pharmacy service.

Managing conflict among a variety of people and groups is a necessary part of creating a high performance pharmacy department. As new pharmacy managers enter the workforce, much of their success depends on how they manage conflict. The goal of this article is to provide a guide for the pharmacy director on conflict in the workplace. By evaluating each type of conflict, we can learn how to respond when it occurs. Resolving conflict requires a unique and individualized approach, and the strategy used may often be based on the situational context and the personality of the employee or manager. The more that pharmacy leaders can engage in conflict resolution with employees and external leaders, the more proactive they can be in achieving positive results. If pharmacy directors understand the source of conflicts and use management strategies to resolve them, they will ensure that conflicts result in a more effective patient-centered pharmacy service.

Managing conflict among a variety of people and groups is a necessary part of creating a high performance pharmacy department. As new pharmacy managers enter the workforce, much of their success depends on how they manage conflict. The goal of this article is to provide a guide for the pharmacy director on conflict in the workplace. By evaluating each type of conflict, we can learn how to respond when it occurs. Resolving conflict requires a unique and individualized approach, and the strategy used may often be based on the situational context and the personality of the employee or manager. The more that pharmacy leaders can engage in conflict resolution with employees and external leaders, the more proactive they can be in achieving positive results. If pharmacy directors understand the source of conflicts and use management strategies to resolve them, they will ensure that conflicts result in a more effective patient-centered pharmacy service.

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(6):543–549

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5006-543

Managing conflict among a variety of people and groups is a necessary part of creating a high performance pharmacy department. Conflict is very common and is expected in the workplace; effectively recognizing and managing conflict creates new opportunities for team members to understand each other, which facilitates personal and professional development.1 Conflict may trigger a “flight or fight” physiologic response; the persons involved in conflict must be able to handle these emotional responses to prevent a negative situation. Effectively managing these emotions in the pharmacy workplace is especially important to prevent failed communication; if avoided or managed inappropriately, conflict can be detrimental to interprofessional collaboration and patient care.2

As new pharmacy managers enter the workforce, much of their success depends on how they manage conflict. Conflict is an inevitable result of human interaction.3 Successfully managing conflict, while focusing on desired outcomes, will ultimately result in improved teamwork, enhanced staff engagement, and positive patient outcomes. By establishing this culture of conflict resolution, pharmacy leaders can encourage communication and discussion throughout the department and ensure that patients are receiving optimal care.4 The goal of this article is to provide a guide for the pharmacy director on conflict in the workplace. It reviews the types of conflict that occur in the pharmacy department and ways to implement appropriate conflict management strategies to achieve a positive outcome.

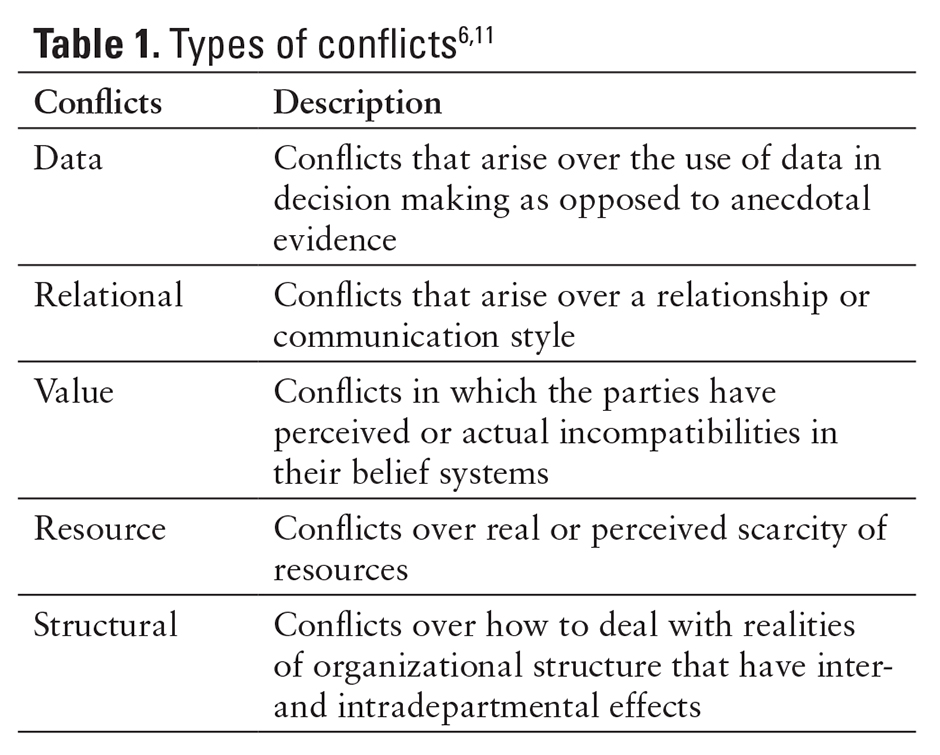

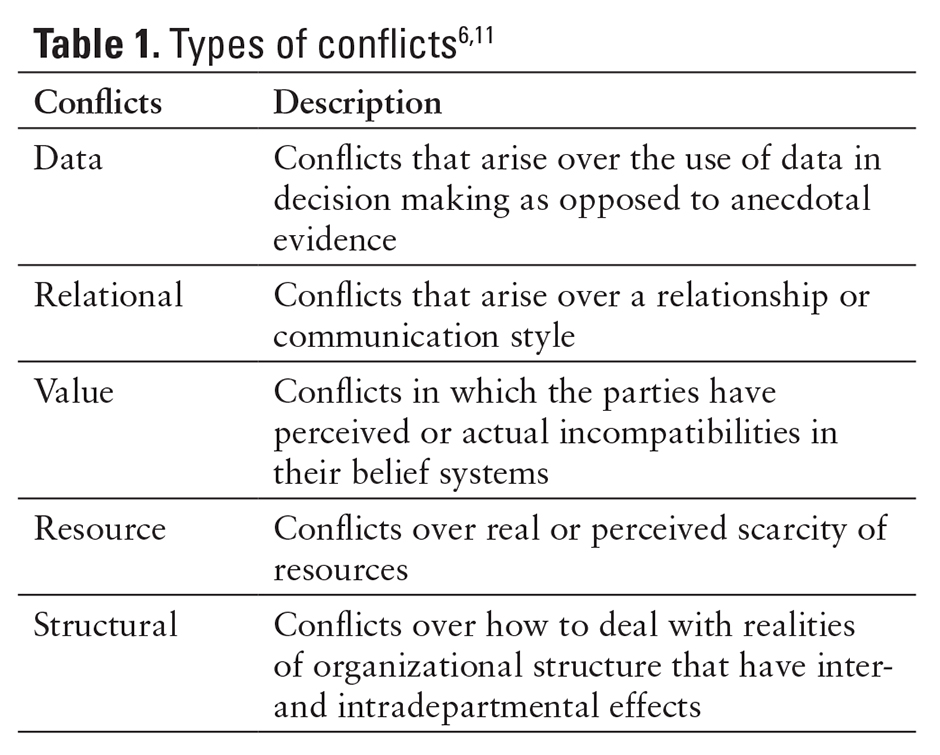

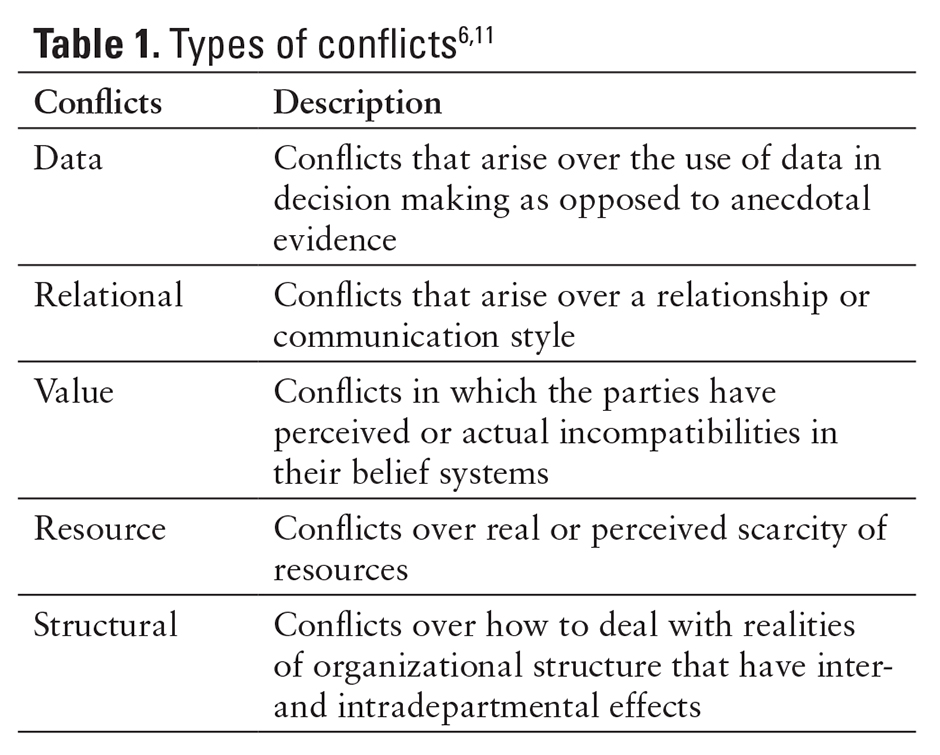

TYPES OF CONFLICT

Directors of pharmacy will face different types of conflict, including intradepartmental conflicts with pharmacists, technicians, and support staff and interdepartmental conflicts with physicians, nurses, and administrators.5 There are 3 overarching categories of conflict: relationship, task, and process.2 Conflict issues that arise can fall into more than one of these categories. Conflicts involving relationships typically arise from personal incompatibilities. Limited resources can also affect relationships and -processes. Task conflicts occur when there are disagreements arising from specific viewpoints and opinions about a particular task. Process conflicts are common when there is disagreement about how to approach a task, such as methods used, group structure, and resource utilization. Table 1 describesthe different types of -conflicts that can occur within the workplace.6 By evaluating each type of conflict, we can gain a greater -understanding of how to respond when issues occur. This is important for managing pharmacy staff and responding to high-stress situations that relate to pharmaceutical care.7

Data Conflicts

When pharmacy managers make decisions about workflow, they utilize data from sources such as pharmacy automation and the electronic medical records. Although these data are often an unbiased source of information, pharmacy staff may become frustrated with this type of decision making.7 Front-line staff may feel that they know what is best for the organization and may push back against the managers’ decisions. An example of this is when staffing needs for the department are being evaluated. Pharmacists may feel that their department is understaffed, whereas data may show that the department is operating efficiently and the manager makes the decision that no more full-time equivalents (FTEs) need to be added. It is the responsibility of the manager to address this disparity in opinion and explain the methodology behind his or her decision. The more that the manager can engage employees in the process of gathering and evaluating data, the more likely they are to trust that source of information. An important way to make data readily available for employees is through the use of dashboards. Dashboards are effective is sharing data in visual form. Information can range from medication errors, staffing ratios, or the turnaround times after medications are ordered.8

Relational Conflicts

Relational conflict is most common; it often arises out of an emotional response or communication style. Some pharmacy employees will respond to conflict with aggression, whereas others will shy away and try to ignore the situation. Neither response will resolve the issue, but rather will cause the conflict to escalate or continue. An example of this may occur when a pharmacy technician in the central pharmacy disagrees with the way in which another technician interacts with them.9 A more senior technician may be condescending every time a new technician procures inventory. If the newer technician does not receive training and background information, they will not succeed in their job. In this case, the more senior pharmacy technician needs to provide discrete education before expecting the new technician to function efficiently.

Value Conflicts

Conflicts in values can occur when employees have perceived or actual incompatibilities in their specific belief systems.2 If staff perceives their pharmacy leadership as not being engaged in the day to day work, they may develop conflicting opinions on the value of required activities. For example, a pharmacy leader who values communication may designate mandatory meetings each week so issues in the pharmacy can be addressed, whereas front-line supervisors or staff may see these meetings as being ineffective or taking time away from direct patient care responsibilities.10

Resource Conflicts

Conflicts over resources may occur within the department, but they more often occur between different professions.7 Although it is not easy to stratify financial assets across a hospital or organization, it is important to have a general approach for resource allocation that is consistent and validated. When one department sees that another is getting special treatment or has more resources, interdepartmental conflicts can arise. An example of this is when pharmacy receives extra FTEs for a move into a new building. Even though this extra help is necessary, the laboratory department receives no extra FTEs. When -pharmacy staff starts to complain that the lab is not processing their specimens quickly, the lab blames their lack of resources. This conflict may create animosity at hospital meetings or affect pharmacy staff who use the lab for patient care research.

Structural Conflicts

Actual or perceived organizational structure or hierarchy can create conflicts. Pharmacy managers need to communicate across the organization, but they should go through the chain of command to avoid conflicts.11 When administrators and directors of pharmacy make decisions for the department, they are subject to external forces and constraints. Often decisions must be made strategically to push projects through the organization without creating political conflict. Although we generally think of structure as having a vertical influence, it can also be horizontal and intradepartmental. An example of structural conflict in the pharmacy is when the manager of the oncology line wants to implement a dose tracking software. This implementation can only be accomplished if the central pharmacy manager is on board. If a decision is made without each manager’s input, then a conflict may occur and the opportunity to implement new software will not happen.

Another structural conflict that can occur in the pharmacy is when a younger pharmacist is hired to oversee more experienced staff. This reporting structure can cause frustration among pharmacists regardless of the new manager’s qualifications. Even though the new manager may have the skills and abilities required to be successful, the staff may be resentful. This issue can cause animosity toward the leader of the organization who made the hiring decision and dissatisfaction among staff.10 It is important that the new manager get involved in the pharmacy operations immediately and have a few good wins with the current staff. This will help staff gain confidence in the newer pharmacy manager and will alleviate the underlying structural conflict.

CAUSES OF CONFLICT

Conflict is caused by a variety of factors; it most often occurs in departments with pharmacists who have different patient care roles. For example, departments that have pharmacists with varying job responsibilities and levels (such as a pharmacy generalist and specialist model) may have underlying tension between pharmacists due to a separation of duties.12 One source of conflict occurs when pharmacy specialists do not review and approve medication orders or dispense and check medications, because they feel this task is “beneath” their skill and responsibility. Also the pharmacy specialist may recommend a medication that is unusual or not normally prescribed without providing adequate communication to the generalist about the order. In both of these situations, the specialist may feel aggravated by the generalist and the generalist may feel degraded by the specialist’s actions.

The World Health Organization and Institute for Safe Medication Practices cite communication breakdown as one of the most common causes of medication-related patient harm. Further, data indicate that more than 60% of medication errors are caused by mistakes in interpersonal communication.5 As noted in the 2005 study by Maxfield and colleagues,5 there are communication breakdowns known as “undiscussables.” These occur when risks to patient safety are widely known, but not discussed. Seven “crucial concerns” were identified that health care professionals had a difficult time communicating effectively. Poorly managed conflict was a central theme to many of these concerns, including those related to poor teamwork, micromanagement, and disrespect.5 All too often, well-intentioned professionals choose to not effectively communicate potential risks to optimal patient care. Lack of communication is consistently identified in root cause analysis conducted after serious or fatal patient safety events. It is the responsibility of the manager to help circumvent this situation to ensure patient care is not compromised.

HEALTHY CONFLICT

The most important challenge for any manager is to address conflict before it becomes a distraction in the workplace. Not all conflict results in a negative outcome. Healthy conflict, which involves leveraging differences to generate open communication and encourage the flow of new ideas, is essential for organizational growth.1,3 This conflict allows more transparent communication, challenges current beliefs or assumptions, and allows resources to be prioritized. Additional specific benefits include enhanced creative thinking, provision of useful feedback to contribute to better decision making, acting as a needed catalyst for change, and resulting in opportunities for innovative and constructive problem solving. Well-managed conflict can encourage personal reflection and feedback that can enable employee development. A good manager will examine the conflict situation and make sure that important needs are met, the relationships between co-workers are strengthened, and the quality of patient care is not compromised. Directors of pharmacy may find themselves in situations where managers are questioning their decisions, pharmacists are doubting their competency in -pharmaceutical care, and external leadership is challenging the strategic plan for the department.

IDENTIFYING CONFLICT

It can be difficult to identify conflict situations before they occur, because the majority of these interactions originate from individual feelings and emotions. Unintentional conflict arises from the inability to communicate effectively with others or the inability to take another’s perspective into consideration.11 Even though conflict may be accidental, it is important that each party’s agenda and goals be considered before making a decision that could warrant an emotional response. Even if the manager is just acting as a sounding board for an employee, his or her response to the situation can escalate or de-escalate the problem. Even with this potential for conflict, managers must be willing to engage in crucial conversations.3 These talks can be effective for creating alignment and agreement by fostering open dialogue around high-stakes, emotional, or risky topics. Learning how to address these topics effectively is an important step in managing conflict, as each employee will interpret conflict from their perspective or personal preferences.13

Often purposeful conflict can be used as a way of challenging others to think differently. Although it can be an effective strategy, it can also be a foreign form of communication for some and can prompt negative feelings. In the department of pharmacy, conflict may be needed to address poor patient care, medication errors, or noncompliance with policies and procedures. This type of conflict provides an opportunity for growth and new understanding, but it should be delivered in such a way that the colleagues or employees will listen. The manager can use conflict as a tool to leverage new ideas for improved communication.

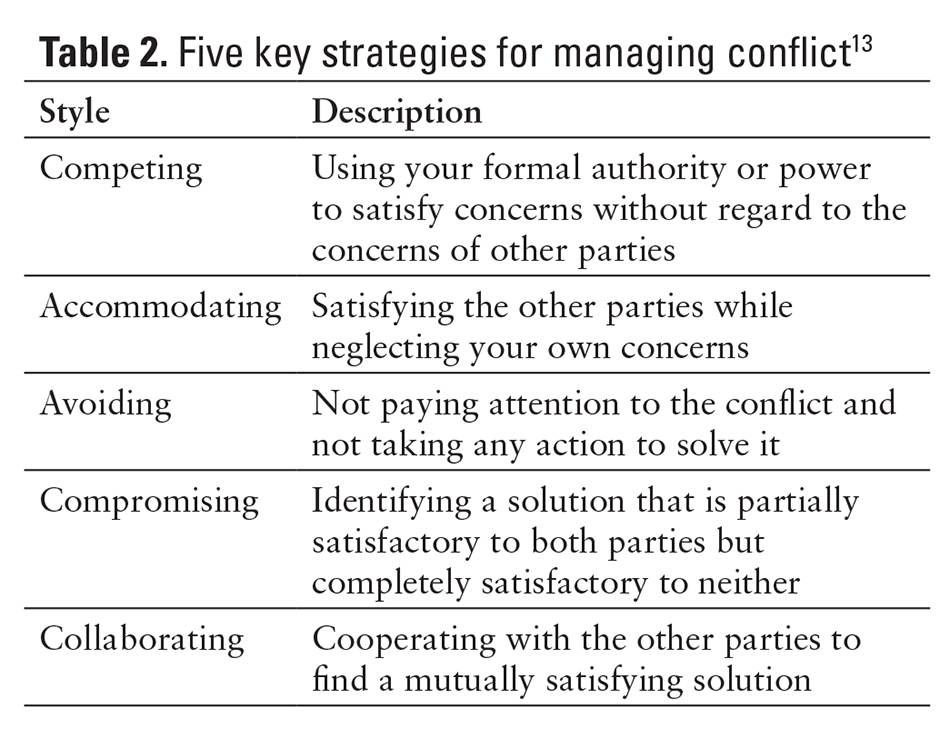

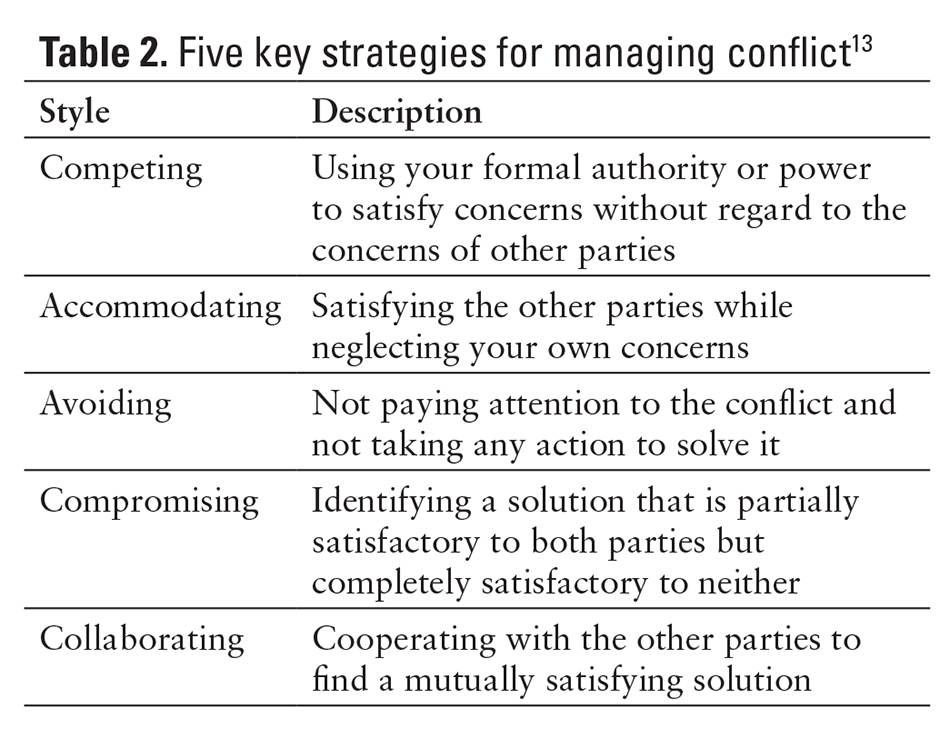

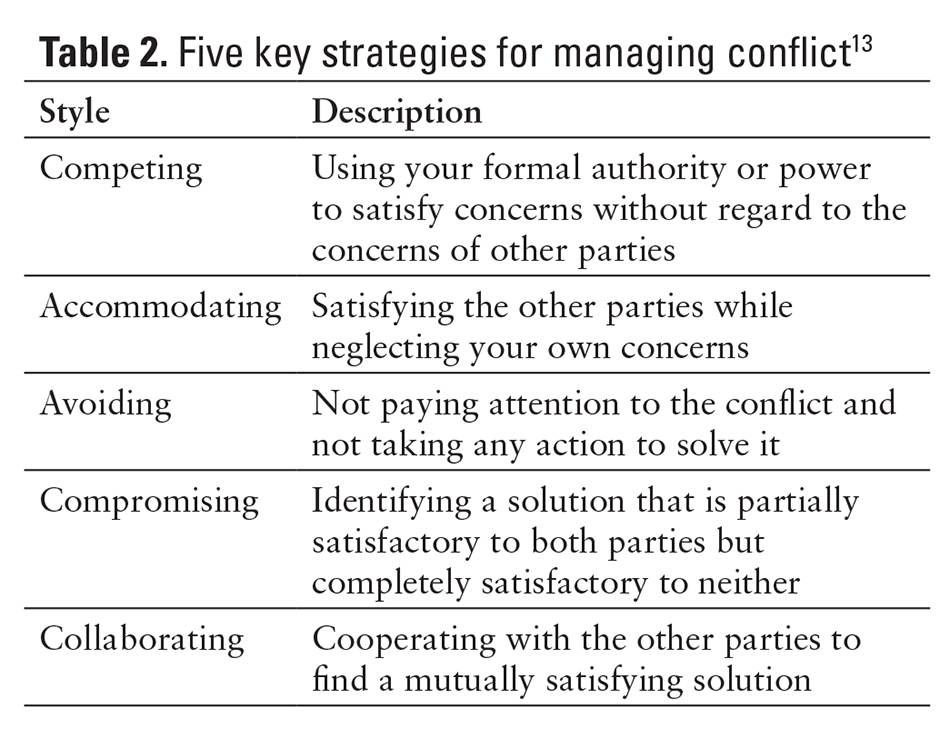

STRATEGIES TO RESOLVE CONFLICT

There are many strategies for managing conflict. According to the Harvard Business Review,13 these strategies are based on the relative importance of the issues, principles, relationships, and values that are at stake. According to the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument, there are 5 key styles for managing conflict: competing, accommodating, avoiding, collaborating, and compromising (Table 2). Each approach is unique and should be used based on the situational context and the personality of the employee or manager.

Competing

When a person uses a competitive style, he or she exerts positional power over an individual or group of people to come to a conclusion. This form of managing conflict is initially effective, but it often does not take into consideration outside viewpoints or collaborative feedback. Directors of pharmacy often use this tactic when a group of employees cannot come to a consensus. Conflict may arise when there is very little objective difference between strategies or operations and disagreements are based on personal preferences. By using this approach, managers can come to a resolution quickly without additional storming.11 Sometimes formal authority is needed when individuals are unsure or confused about how to respond to a situation, such as when a pharmacy manager is opening up an additional satellite pharmacy. During this transition, conflict may arise; but it is the responsibility of the manager to utilize his or her formal authority to help each employee stick to the operational workflows and remain focused.13 In this situation, pharmacists need to follow one voice.

Accommodating

Some managers may be more forceful in the way they approach conflict, whereas others are more -accommodating. In the accommodating approach, the pharmacy manager may satisfy the concerns of the employees or other managers while neglecting his or her own. This can be dangerous for the organization, as conflicting viewpoints are needed to promote change and growth. If a manager is too accommodating, employees will begin to force their own agendas and not always do what is best for the organization. By not challenging employees within their pharmacy practice model and accommodating their preferences, an accommodating leader could decrease the department’s efficiency and prioritization of patient care.7 Health systems look to pharmacy managers to best serve the needs of their patients in a cost-effective manner.

In some situations, the accommodating approach is ideal. If an issue has no direct bearing on the operations of the pharmacy or direct patient care, a manager can accommodate the wishes of the employees. An example of this situation is a conflict that can arise over the use of the conference room. The conference room must be open for meetings during the day, but the employees want to use it as a break room. The manager can decide to allow it to be used by the employees as a break room at night as long as they clean up after their shift, thus satisfying the needs of both the department and the employees.

Avoiding

Another approach to conflict is avoidance. Many employees avoid a manager or supervisor when they disagree with their rules or policies.1 Avoidance reduces the escalation of conflict in the relationship, but it does not solve the underlying issue. When employees continually avoid conflict, they become frustrated and therefore do not take action to resolve the conflict. This often happens when pharmacy technicians have a lack of involvement in the organization and do not feel as though they are valued. For example, if the technicians do not raise the issue of a pharmacy technician career ladder, they will never have the opportunity to pursue more value-added tasks.9 In this case, the manager finds out that the employees are disengaged through the employee satisfaction survey that occurs only once a year. Employees and managers need to understand that if conflict is never addressed, communication will not improve and growth will not occur.

Compromising

Compromise is often necessary in order for a manager and employee to resolve their conflict and to move forward. In compromise, the solution is partially satisfactory to both parties but it is not completely satisfactory to either person; even so, -compromise can help settle a conflict.13 Departments may need to work out a compromise if they need additional resources. The director of pharmacy might have to compromise when working with their physician counterparts. The most common example of this type of conflict resolution is when a medical team wishes to prescribe a costly medication. The director of pharmacy always wants to do what is in the patients’ best interests, but there may be more cost-effective alternatives that provide similar outcomes. To meet the needs of both groups, the issue may be brought to the pharmacy and therapeutics committee. It may be decided that a medication use evaluation should be performed so that the physician may prescribe the medication under strict guidelines. In this scenario, both parties had to compromise to meet their own agendas and preserve patient care.

Collaborating

The last form of conflict management involves collaborating. This approach is most successful in mitigating conflict, because it involves the cooperation of both parties as they strive to understand each other’s concerns and work to find a mutually satisfying solution. For collaborating to be effective, all parties must recognize the interests and abilities of the other parties. These interests and desired outcomes should be thoroughly explored to maximize problem solving. All those involved should expect to modify their views as work progresses.11,14 In the collaboration model, the following steps should be taken:

- Identify the problem

- Identify all possible solutions (brainstorm)

- Decide on the best solution

- Determine how to implement the solution

- Assess the outcome

Pharmacists want more autonomy in the pharmacy, but they are bound by the rules and regulations of the board of pharmacy. When pharmacists begin to practice outside their scope, the manager may have to intervene. Rather than simply stating that a pharmacist cannot order laboratory tests independently, the manager must find a solution that meets the needs of patient care and complies with the rules of the organization. In this case, the manager may decide to have their pharmacists become credentialed and privileged. This would require changing the current policies on pharmacist practice, but it will give the pharmacists the ability to function more independently under the license of a prescribing physician.

Collaborative problem solving leverages the expertise of all individuals for the betterment of the patients. The pharmacy manager utilizes the knowledge of the pharmacist for pharmacotherapy and drug-drug interactions, while the physician and nurse utilize diagnostic skills to formulate patient care plans. Often the team needs to work together for complex patient cases, where the delivery of care may involve risky procedures or high cost medications.

RESULTS OF CONFLICT

Conflict results in 1 of 3 outcomes: win-lose, lose-lose, or win-win. The goal of all conflict resolution should be a win-win outcome where each party benefits.

In most cases, if an employee challenges a manager about a situation and there is no room for negotiation, the manager will win the conflict. The conflict may be resolved, but the win-lose result may create animosity among employees and cause them to avoid conflicting situations, even when they may have ideas for improvement.6

Conflicts that end in a lose-lose situation can be most dangerous to an organization. Neither the manager nor employee are satisfied, and there is a high likelihood that the conflict may occur again and may become more severe over time. Each time the same conflict arises, it becomes more of a distraction, and little is done to improve the situation.

The most desirable ending to conflict is the win-win result. This occurs when a manager understands the background to the conflict and successfully uses a mitigation strategy that plays to both parties. Often both sides are collaborating to determine how each side can satisfy its needs. If a pharmacy manager is interested in having more cross-trained pharmacists, he or she can engage each person to find out what his or her specific interests are. This way each pharmacist gets to rotate through areas of the pharmacy, while the manager can have more cross-trained employees when individuals get sick or go on medical leave. Working together through communication can lead to satisfactory results.6

CONCLUSION

Conflict occurs every day in every organization. While conflict can cause confusion and disagreement, it also creates new opportunities to think differently. Without conflict, there would be no impetus for growth.13 The more that pharmacy leaders can engage in conflict resolution with their employees and external leaders, the more proactive they can be in ensuring postive results. It is the leaders’ responsibility to manage conflict and to allow others the opportunity to voice their opinions. The more skilled managers become in handling differences and changes without creating or getting directly involved in the drama of conflict, the more successful their pharmacy departments and organizations will become. Consider these final points:

- Conflict is a natural occurrence in all organizations and should not be feared.

- Although conflict may make some feel uncomfortable, it is a natural catalyst for change.

- Utilize conflict as a tool in your organization to engage employees of all areas in department improvements.

- It is important to understand each party’s needs in determining how to resolve conflict.

- There is not one best way to manage conflict, as it depends on the unique situation.

If leaders apply these strategies in their daily management, they will ensure that conflict is used positively to build a more effective patient-centered pharmacy service.

REFERENCES

- Tekleab A, Quigley N, Tesluk P. A longitudinal study of team conflict, conflict management, cohesion, and team effectiveness. Group Organization Manage. 2009:34(2):170-201.

- Jehn KA, Mannix EA. The dynamic nature of conflict:

A longitudinal study. Acad Manage J. 2001;44(2):238–251. - Managing conflict [editorial]. Econ Political Weekly. 1999:34(27):1739. http://www.epw.in/editorials/managing-conflict.html

- Kaufman J. Conflict management education in medicine: Considerations for curriculum designers. Online J Workforce Educ Dev. 2011;5(1):1-17.

- Maxfield D, Grenny J, McMillan R, Patterson K, Switzler A. The silent treatment why safety tools and checklists aren’t enough to save lives. Vitalsmarts Industry Watch. http://www.silenttreatmentstudy.com/silencekills/SilenceKills.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2015.

- Coburn C. Negotiation conflict styles. http://hms.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/assets/Sites/Ombuds/files/NegotiationConflictStyles.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2015.

- Anyika E. Conflict management styles in academic and hospital pharmacy practice areas in affiliated tertiary institutions in Lagos, Nigeria. J Hosp Admin. 2013;2(4):120-125.

- Bahl V, McCreadie SR, Stevenson JG. Developing dashboards to measure and manage inpatient pharmacy costs. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(17):1859-1866.

- Canadian Pharmacists’ Association, Management Committee. Moving Forward: Human Resources for the Future, Final Report. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2008.

- Austin Z, Gregory P, Martin JC. Pharmacists’ experience of conflict in community practice. Res Social Admin Pharm. 2010;6(1):39-48.

- Gratton L, Erickson TJ. Eight ways to build collaborative teams. Harvard Business Rev. 2007;85(11):100-109.

- Austin Z, Gregory P, Martin C. A conflict management scale for pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(7):122.

- Weiss J, Hughes J. Want collaboration? Accept—and actively manage—conflict. Harvard Business Rev. 2005;83(3):92-101.

- Gerardi D, Fontaine D. True collaboration: Envisioning new ways of working together. Adv Crit Care. 2007;18(1):10-14.

*Senior Pharmacy Resident, Health-System Pharmacy Administration, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio; †Center for Medication Safety Advancement, Purdue University College of Pharmacy, Indianapolis, Indiana; ‡Administrator, Pharmacy Services, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and College of Pharmacy, Columbus, Ohio