Formulary Drug Reviews

Edoxaban

Dennis J. Cada, PharmD, FASHP, FASCP (Editor)*; Danial E. Baker, PharmD, FASHP, FASCP†; and Kyle Ingram, PharmD‡

Formulary Drug Reviews

Edoxaban

Dennis J. Cada, PharmD, FASHP, FASCP (Editor)*; Danial E. Baker, PharmD, FASHP, FASCP†; and Kyle Ingram, PharmD‡

Formulary Drug Reviews

Edoxaban

Dennis J. Cada, PharmD, FASHP, FASCP (Editor)*; Danial E. Baker, PharmD, FASHP, FASCP†; and Kyle Ingram, PharmD‡

Each month, subscribers to The Formulary Monograph Service receive 5 to 6 well-documented monographs on drugs that are newly released or are in late phase 3 trials. The monographs are targeted to Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committees. Subscribers also receive monthly 1-page summary monographs on agents that are useful for agendas and pharmacy/nursing in-services. A comprehensive target drug utilization evaluation/medication use evaluation (DUE/MUE) is also provided each month. With a subscription, the monographs are sent in print and are also available on-line. Monographs can be customized to meet the needs of a facility. A drug class review is now published monthly with The Formulary Monograph Service. Through the cooperation of The Formulary, Hospital Pharmacy publishes selected reviews in this column. For more information about The Formulary Monograph Service, call The Formulary at 800-322-4349. The July 2015 monograph topics are ivabradine, dinutuximab, glycopyrronium bromide/indacaterol, patriromer, and idarucizumab. The Safety MUE is on ivabradine.

Generic Name: Edoxaban

Proprietary Name: Savaysa (Daiichi Sankyo)

Approval Rating: 1S

Therapeutic Class: Factor Xa inhibitors

Similar Drugs: Apixaban, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban

Sound- or Look-Alike Names: Doribax, Erbitux, Etidocaine

Each month, subscribers to The Formulary Monograph Service receive 5 to 6 well-documented monographs on drugs that are newly released or are in late phase 3 trials. The monographs are targeted to Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committees. Subscribers also receive monthly 1-page summary monographs on agents that are useful for agendas and pharmacy/nursing in-services. A comprehensive target drug utilization evaluation/medication use evaluation (DUE/MUE) is also provided each month. With a subscription, the monographs are sent in print and are also available on-line. Monographs can be customized to meet the needs of a facility. A drug class review is now published monthly with The Formulary Monograph Service. Through the cooperation of The Formulary, Hospital Pharmacy publishes selected reviews in this column. For more information about The Formulary Monograph Service, call The Formulary at 800-322-4349. The July 2015 monograph topics are ivabradine, dinutuximab, glycopyrronium bromide/indacaterol, patriromer, and idarucizumab. The Safety MUE is on ivabradine.

Generic Name: Edoxaban

Proprietary Name: Savaysa (Daiichi Sankyo)

Approval Rating: 1S

Therapeutic Class: Factor Xa inhibitors

Similar Drugs: Apixaban, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban

Sound- or Look-Alike Names: Doribax, Erbitux, Etidocaine

Each month, subscribers to The Formulary Monograph Service receive 5 to 6 well-documented monographs on drugs that are newly released or are in late phase 3 trials. The monographs are targeted to Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committees. Subscribers also receive monthly 1-page summary monographs on agents that are useful for agendas and pharmacy/nursing in-services. A comprehensive target drug utilization evaluation/medication use evaluation (DUE/MUE) is also provided each month. With a subscription, the monographs are sent in print and are also available on-line. Monographs can be customized to meet the needs of a facility. A drug class review is now published monthly with The Formulary Monograph Service. Through the cooperation of The Formulary, Hospital Pharmacy publishes selected reviews in this column. For more information about The Formulary Monograph Service, call The Formulary at 800-322-4349. The July 2015 monograph topics are ivabradine, dinutuximab, glycopyrronium bromide/indacaterol, patriromer, and idarucizumab. The Safety MUE is on ivabradine.

Generic Name: Edoxaban

Proprietary Name: Savaysa (Daiichi Sankyo)

Approval Rating: 1S

Therapeutic Class: Factor Xa inhibitors

Similar Drugs: Apixaban, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban

Sound- or Look-Alike Names: Doribax, Erbitux, Etidocaine

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(7):619–634

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5007-619

INDICATIONS

Edoxaban is a factor Xa inhibitor approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) and for the treatment of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).1 However, in patients with nonvalvular AF, edoxaban should not be used when creatinine clearance (CrCl) is greater than 95 mL/min because of an increased risk of ischemic stroke compared with use of warfarin. Patients with DVT should be treated with a parenteral anticoagulant for 5 to 10 days prior to starting edoxaban therapy.1 Edoxaban is being evaluated for use in association with cardioversion of AF; peripheral arterial disease; venous thromboembolism (VTE) in cancer; and VTE prophylaxis after total knee replacement, hip fracture surgery, or hip arthroplasty. It is also being evaluated for the treatment of DVT in comparison with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) plus warfarin therapy.2-11

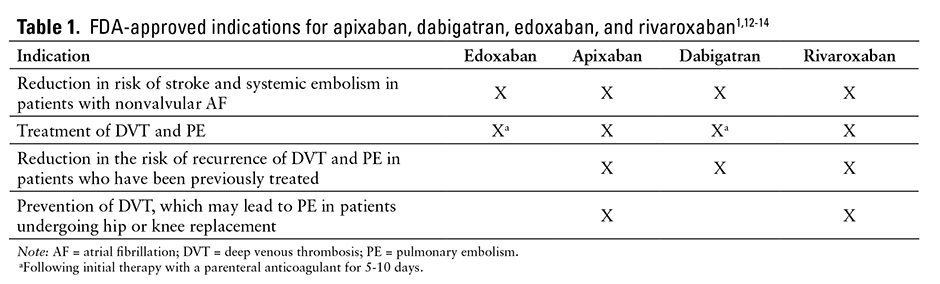

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved indications for apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban are summarized in Table 1.1,12-14

CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Edoxaban is a direct, selective, oral inhibitor of free and clot-bound factor Xa.15-18 The coagulation cascade comprises the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, which converge at factor Xa. The conversion of prothrombin (factor II) to thrombin (factor IIa) is mediated by factor Xa, which catalyzes the formation of a fibrin clot via conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, ultimately leading to thrombus formation and clotting.15,17-19 By inhibiting factor Xa, edoxaban is able to block the final stages of the coagulation cascade. Edoxaban is selective for factor Xa and inhibits downstream clotting factors, such as factor IIa and fibrin, while factors XIIa, XIa, IXa, or VIIa are unaffected.15,18 According to an in vitro study evaluating the effects of edoxaban on pooled platelet-poor human plasma, edoxaban produces a concentration-dependent increase in activated partial thromboplastin time, modified plasma thromboplastin, international normalized ratio (INR), heparin test, and prothrombinase-induced clotting time.20 Additionally, edoxaban does not affect platelet activation, tissue factor pathway inhibition, or endothelial breakdown.21

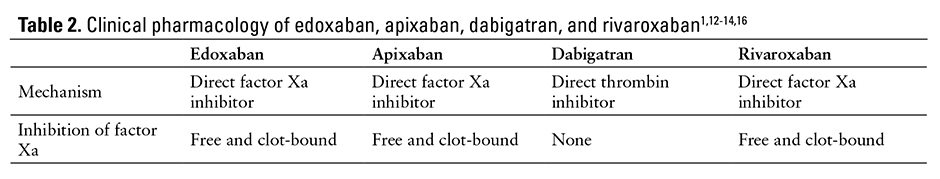

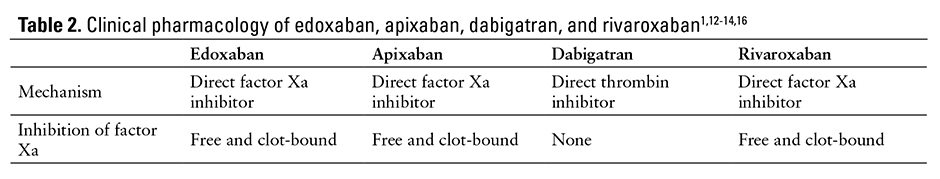

The pharmacologic properties of edoxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban are listed in Table 2.1,12-14,16

PHARMACOKINETICS

Edoxaban is a rapidly absorbed active drug with a peak plasma concentration of 1 to 2 hours.1,17,20,22,23 Its absolute bioavailability is 62%.1 Edoxaban demonstrates linear pharmacokinetics within therapeutic dose ranges, and there are no significant effects on pharmacokinetics when coadministered with meals.1,23-26

Steady-state volume of distribution is 107 L. Protein binding is 55%. The drug is primarily metabolized via hydrolysis (approximately 25% total dose), with approximately one-third eliminated renally and two-thirds eliminated hepatically.1,17,23 Unchanged edoxaban elimination in the urine accounts for 50% of the drug’s total clearance.1,17

Edoxaban is minimally metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP-450) enzymes, although it is a substrate of the human efflux transporter

P-glycoprotein (P-gp).1,19,27 Edoxaban elimination half-life is 8 to 14 hours in patients with mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment; in patients requiring peritoneal dialysis, the half-life and exposure increased with severity of renal impairment.1,17,27,28 Hemodialysis had little impact on the pharmacokinetics of edoxaban and its major metabolite (M4) but did alter the profile of minor metabolites (M1 and M6).22 Steady-state concentrations occur within 3 days.1

The predictable pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profiles eliminate the need for routine monitoring; additionally, in phase 3 clinical trials, edoxaban did not require laboratory monitoring.16,23

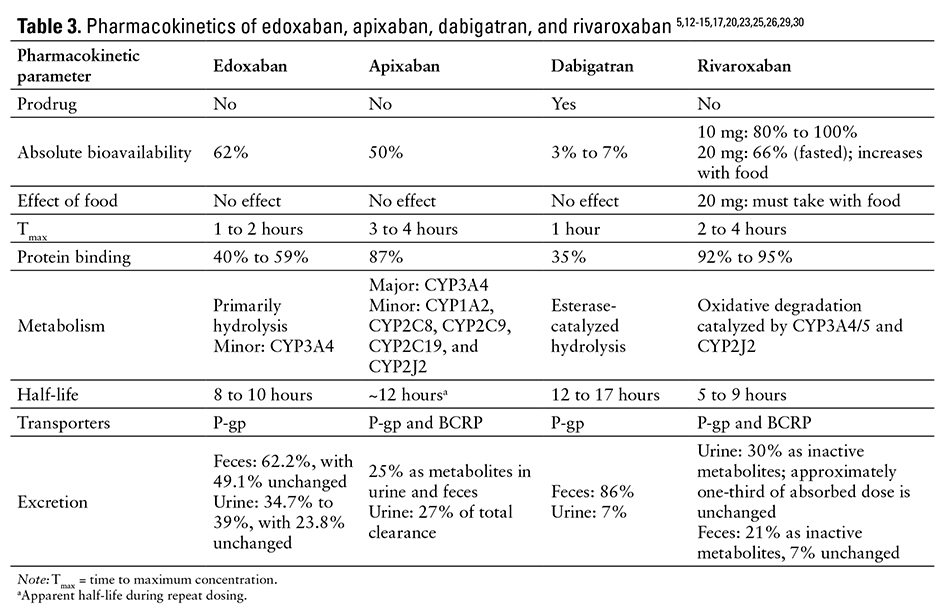

The pharmacokinetic parameters of edoxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban are listed in Table 3.5,12-15,17,20,23,25,26,29,30

COMPARATIVE EFFICACY

Indication: Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism

Guidelines

Guideline: Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines

Reference: Kearon C, et al, 201231

Comments: The guidelines advocate use of short-term low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) therapy, unfractionated heparin, or fondaparinux for initial treatment of most DVT or PE; LMWH or fondaparinux therapies are generally preferred. Warfarin is generally recommended for long-term therapy and is initiated concomitantly with initial treatment, except in patients with cancer for whom LMWH therapy is preferred over warfarin. Warfarin and LMWH therapy were given weak recommendations over dabigatran and rivaroxaban because of limited information available on the newer agents. Edoxaban was not addressed in the guidelines.

Studies

Drug: Edoxaban vs Warfarin

Reference: Büller HR, et al, 201316

Study Design: Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, noninferiority, multicenter, international study

Study Funding: Daiichi-Sankyo

Patients: 8,292 patients with acute, symptomatic DVT involving the popliteal, femoral, or iliac veins or acute symptomatic PE. Patients were excluded if they had received more than 48 hours of therapeutic heparin treatment or more than 1 dose of warfarin. Patients were also excluded if they had other indications for warfarin therapy, continued to receive treatment with aspirin at a dosage of more than 100 mg/day or dual antiplatelet therapy, or had CrCl less than 30 mL/min. Mean patient age was 55.8 years; 57% were male; 6.5% had CrCl between 30 and 50 mL/min; approximately 17.8% received edoxaban 30 mg at randomization; 65.9% and 65.4% had an unprovoked DVT or PE, respectively; and 19% and 17.9% had a history of VTE in the edoxaban and warfarin groups, respectively.

Intervention: All patients received at least 5 days of treatment with enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive warfarin (n = 4,122) started on day 1 or edoxaban (n = 4,118) started after discontinuation of heparin, and each group received matching placebos. Patients received edoxaban 60 mg (or 30 mg if CrCl was 30 to 50 mL/min, body weight was no greater than 60 kg, or in cases of concomitant treatment with P-gp inhibitors) once daily with or without food, or warfarin (with dose adjustment to maintain an INR of 2 to 3). Sham INR values were reported to investigators for patients receiving edoxaban. Treatment with edoxaban or warfarin was continued for 3 to 12 months; duration was determined by the treating physician. A committee unaware of study group assignments adjudicated all suspected outcomes.

Results

Primary Endpoint(s)

- The composite incidence of DVT and nonfatal or fatal PE occurred in 130 of 4,118 (3.2%) edoxaban-treated patients and 146 of 4,122 (3.5%) warfarin-treated patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7 to 1.13; P < .001 for noninferiority). Noninferiority was achieved because the upper limit of the HR was less than 1.5.

Secondary Endpoint(s)

- Incidence of DVT or nonfatal or fatal PE and death from cardiovascular causes occurred in 114 of 4,118 (2.8%) edoxaban-treated patients and 120 of 4,122 (2.9%) warfarin-treated patients (P = .68 for superiority).

- The incidence of DVT or nonfatal or fatal PE and death from any cause occurred in 228 of 4,118 (5.5%) edoxaban-treated patients and 228 of 4,122 (5.5%) warfarin-treated patients (P = 1 for superiority).

- The net clinical benefit was composed of a composite of symptomatic recurrent VTE or major bleeding in 120 of 4,118 (2.9%)

edoxaban-treated patients and 144 of 4,122 (3.5%) warfarin-treated patients (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.65 to 1.06; P = .14).

Endpoint(s)

- The principle safety outcome was a composite of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding during on-treatment periods, which occurred in 8.5% of edoxaban-treated patients and 10.3% of warfarin-treated patients (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.94; P = .004 for superiority).

Comments: In this cohort, 836 patients were from the United States and Canada. Once-daily edoxaban was noninferior to warfarin for the prevention of VTE in patients with DVT or PE and caused significantly less bleeding of any kind. INR was 2 to 3 for 63.5% of the time, above 3 for 17.6% of the time, and below 2 for 18.9% of the time. Adherence to edoxaban was 80% or more in 99% of patients, and 40% of patients were treated for 12 months. The primary efficacy outcome occurred at the highest rate during the first 30 days of treatment.

Limitations: Adverse reactions other than bleeding were not reported. Prior to randomization, patients could be treated with enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin, although only 299 patients were initially treated with unfractionated heparin.

Indication: Reduction in Risk of Stroke and Systemic Embolism in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation

Guidelines

Guideline: Oral antithrombotic agents for the prevention of stroke in nonvalvular AF: A science advisory for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association

Reference: Furie KL, et al, 201232

Comments: The guidelines acknowledge that warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban are all indicated for the prevention of first and recurrent stroke in patients with nonvalvular AF. The guidelines recommend that selection of an agent be individualized on the basis of risk factors, cost, tolerability, patient preference, potential for drug interactions, and time in INR therapeutic range if the patient has been taking warfarin. Dabigatran and apixaban are both listed as alternatives to warfarin in patients with nonvalvular AF and 1 additional stroke risk factor. Rivaroxaban is listed as an alternative to warfarin in patients with nonvalvular AF who are at moderate to high risk of stroke due to a history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or systemic embolism or the presence of 2 or more additional stroke risk factors. Edoxaban was not addressed in the guidelines.

Guideline: 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society

Reference: January CT, et al, 201433

Comments: For patients with nonvalvular AF with prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, use of an oral anticoagulant (eg, warfarin [INR 2 to 3], dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) is recommended. Patients treated with warfarin should have their INR checked at least weekly during initiation and at least monthly once stabilized. For patients with nonvalvular AF who are unable to maintain a therapeutic INR level with warfarin, any of the direct thrombin or factor Xa inhibitors (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban) can be used. If the patient has moderate to severe chronic kidney disease, the direct thrombin or factor Xa inhibitor dose may need to be reduced. Edoxaban was not approved at the time these guidelines were developed.

Studies

Drug: Edoxaban vs Warfarin

Reference: Giugliano RP, 2013 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 study)5,34-37

Study Design: Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, noninferiority, multicenter, international study

Study Funding: Daiichi-Sankyo

Patients: 21,105 patients with a CHADS2 score of at least 2 and AF confirmed by electrical tracing within 1 year of enrollment were included in the study; 21,026 patients received study medication. Both vitamin K antagonist–experienced and vitamin K antagonist–naive patients were eligible. Patients with severe renal impairment (CrCl less than 30 mL/min), AF due to a reversible disorder, use of dual antiplatelet therapy, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, and conditions associated with a risk of bleeding were excluded. Median age was 72 years (interquartile range [IQR], 64 to 78 years); 77.4% of patients had a CHADS2 score of up to 3, and 22.6% had a CHADS2 score of 4 to 6; 57.6% had congestive heart failure; 36.1% had diabetes mellitus; 58.9% had previously taken a vitamin K

antagonist for at least 60 days; and 22.2% of patients were in the United States. Patients were treated for a median of 907 days, with a median follow-up of 1,022 days.

Intervention: Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban 30 mg once daily (low dose), edoxaban 60 mg once daily (high dose), or dose-adjusted warfarin to maintain an INR of 2 to 3. Patients were also stratified according to their CHADS2 score (scores of 2 or 3 vs scores of 4, 5, or 6) and need for a reduction in edoxaban dose (eg, estimated CrCl 30 to 50 mL/min; body weight 60 kg or less; concomitant use of verapamil, quinidine, or dronedarone [P-gp inhibitors]). Patients receiving a vitamin K antagonist were randomized when INR was 2.5 or less. At randomization, approximately 29% of patients were receiving aspirin, 2.3% were receiving thienopyridine, 12% were receiving amiodarone, and 30% were receiving digoxin. At randomization, 25.3% of patients received a reduced dose of edoxaban or matching placebo; after randomization, 7.1% received a dose reduction and 1.2% received a dose increase.

Results

Primary Endpoint(s)

- The composite of stroke and systemic embolic events was evaluated in the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) population (randomized and received at least 1 dose of study medication) and occurred in 232 patients taking warfarin (annualized rate of 1.5%), 253 patients taking low-dose edoxaban (annualized rate of 1.61%; HR vs warfarin, 1.07; 97.5% CI, 0.87 to 1.31; P = .005 for noninferiority, P = .44 for superiority), and 182 patients taking high-dose edoxaban (annualized rate of 1.18%; HR vs warfarin, 0.79; 97.5% CI, 0.63 to 0.99; P < .001 for noninferiority, P = .02 for superiority).

- For the superiority analysis in the ITT population, the annualized rate of the composite of stroke and systemic embolic events was 1.8% with warfarin, 2.04% with low-dose edoxaban (HR, 1.13; 97.5% CI, 0.96 to 1.34; P = .1), and 1.57% with high-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.87; 97.5% CI, 0.73 to 1.04; P = .08).

- The annualized rate of hemorrhagic stroke was 0.47% with warfarin, 0.16% with low-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.5; P < .001), and 0.26% with high-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.77; P < .001).

- The annualized rate of ischemic stroke was 1.25% with warfarin, 1.77% with low-dose edoxaban (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.67; P < .001), and 1.25% with high-dose edoxaban (HR, 1; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.19; P = .97).

- Major bleeding occurred at an annualized rate of 3.43% with warfarin, 1.61% with low-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.41 to 0.55; P < .001), and 2.75% with high-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.91; P < .001).

- The rates of life-threatening bleeding were 0.78% with warfarin, 0.25% with low-dose edoxaban, and 0.4% with high-dose edoxaban (P < .001 for each dose of edoxaban compared with warfarin).

- The rates of intracranial bleeding were 0.85% with warfarin, 0.26% with low-dose edoxaban, and 0.39% with high-dose edoxaban (P < .001 for each dose of edoxaban compared with warfarin).

- The rates of major bleeding plus clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding were 13.02% with warfarin, 7.97% with low-dose edoxaban, and 11.1% with high-dose edoxaban (P < .001 for each dose of edoxaban compared with warfarin).

- The annualized rate of major GI bleeding was 1.23% with warfarin, 0.82% with low-dose edoxaban, and 1.51% with high-dose edoxaban.

Secondary Endpoint(s)

- Treatment with edoxaban was associated with lower annualized rates of death from cardiovascular causes than treatment with warfarin: 3.17% with warfarin compared with 2.74% with high-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.97; P = .01) and 2.71% with low-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.96; P = .008).

- The annualized rate of net clinical benefit (eg, death from any cause, stroke, systemic embolic event, major bleeding) was 8.11% with warfarin, 6.79% with low-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.9; P < .001), and 7.26% with high-dose edoxaban (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.96; P = .003).

Endpoint(s)

- Stroke or systemic embolic events, especially ischemic stroke, occurred more frequently in the low-dose edoxaban group (333 patients) compared with the high-dose edoxaban group (236 patients) (P < .001). However, hemorrhagic stroke occurred more frequently with the high-dose regimen (49 vs 30 events).

Comments: Analysis included all randomized patients who took at least 1 dose of medication. To meet noninferiority for the primary efficacy endpoint, the upper bound of the 2-sided 97.5% CI for the HR for edoxaban compared with warfarin must be less than 1.38. The study was powered at 87%, with approximately 672 primary endpoint events; however, only 667 events occurred during the study period. In subgroup analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint, there were differences

(P < .05) between edoxaban and warfarin groups, depending on previous receipt of a vitamin K antagonist, concurrent aspirin use, and concurrent amiodarone use. In the warfarin group, INR was between 2 and 3 for 68.4% of the treatment period and between 1.8 and 3.2 for 83.1% of the treatment period. There was a very low rate of missing data (0.5%), and the study did not use any imputed data method to replace any missing data; instead, all analyses were performed on observed data only. Analysis by prespecified age groups found a consistent impact on efficacy and safety associated with edoxaban and an increased risk of bleeding associated with age in both groups.37 Other prespecified subgroup analyses found no difference in efficacy between patients with and without heart failure in incidence of systemic embolic events or stroke; frequency of noncerebral, arterial embolism was less than that of stroke but was associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and concomitant use of antiplatelet therapy with edoxaban resulted in fewer bleeding events compared with patients treated with antiplatelet therapy and warfarin.38-40

Reference: Chung N, et al, 201141

Study Design: Phase 2, randomized, double-blind, open-label, parallel-group, multicenter, international, dose-finding study

Study Funding: Daiichi-Sankyo

Patients: 234 patients from Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore with documented nonvalvular AF and CHADS2 score of at least 1 were included. Mean age was approximately 65 years; 65% were male; 39% used concomitant aspirin; and 110, 63, and 61 patients had a CHADS2 score of 1, 2, and 3 to 6, respectively.

Intervention: Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban 30 mg once daily (n = 79), edoxaban 60 mg once daily (n = 80), or warfarin (n = 75; with dose adjusted to maintain INR between 2 and 3) for 3 months.

Results

Primary Endpoint(s)

- The composite of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was 20.3% (95% CI, 12.9 to 30.4) for edoxaban 30 mg, 23.8% (95% CI, 15.8 to 34.1) for edoxaban 60 mg, and 29.3% (95% CI, 20.2 to 40.4) for warfarin. No major bleeding events occurred in the edoxaban group, and 2 (2.7%) major bleeding events (retinal hemorrhage and upper GI hemorrhage) occurred in warfarin-treated patients. Clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding occurred in 0%, 7.5%, and 4%, and minor bleeding occurred in 20.3%, 18.8%, and 22.7% of patients treated with edoxaban 30 mg, edoxaban 60 mg, and warfarin, respectively.

Secondary Endpoint(s)

- Major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 2.5%, 3.8%, and 1.3% of patients with use of edoxaban 30 mg, edoxaban 60 mg, and warfarin, respectively. One death occurred in a patient receiving edoxaban 60 mg 13 days after premature discontinuation.

- Edoxaban plasma concentration was approximately 2-fold greater in patients receiving 60 mg compared with 30 mg, both measured at trough and 1 to 3 hours after dosing.

Comments: Patients who received at least 1 dose and 1 postdose efficacy assessment were included in the primary analysis set. The compliance rate (75% or greater of scheduled doses) was 96% or higher in all treatment groups. The INR rates for the warfarin group during study days 56 to 84 were less than 2 in 43.9%, between 2 and 3 in 45.1%, 1.8 to 3.2 in 57.1%, and greater than 3 in 10.9%; 48.3% of these patients were warfarin naive prior to the study. Rates of bleeding were greater in patents weighing less than 60 kg, which indicates that a lower edoxaban dose may be required. Once-daily edoxaban had a similar rate of bleeding as warfarin in an Asian cohort with a CHADS2 score of at least 1; however, the investigators noted that the low overall incidence of bleeding events suggest that the study was underpowered to demonstrate a statistically significant difference among the groups.

Limitations: The study included a small nondiverse Asian cohort, was of short duration, and was not designed to measure efficacy outcomes.

Reference: Weitz JI, 201042

Study Design: Phase 2, randomized, double-blind (edoxaban doses only), open-label (edoxaban vs warfarin), parallel-group, multicenter, international, safety study

Study Funding: Daiichi-Sankyo

Patients: 1,146 patients with persistent nonvalvular AF and a CHADS2 score of at least 2 were included. Women were only included if they were at least

2 years postmenopausal or had undergone a bilateral oophorectomy. Patients were excluded if they had mitral valve disease, endocarditis, a mechanical valve, or CrCl less than 30 mL/min. Baseline characteristics were similar among groups: the overall group age was approximately 65 years, 63% had a CHADS2 score of 2, 64% were warfarin naive, 62% were male, 97% were White, and 8% were from North America.

Intervention: Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban 30 mg once daily (n = 235), edoxaban 30 mg twice daily (n = 245), edoxaban 60 mg once daily (n = 235), edoxaban 60 mg twice daily (n = 180), or warfarin (n = 251). Warfarin was dose adjusted to maintain an INR of 2 to 3. The edoxaban arms were blinded in respect to the dose; however, warfarin was open label. All patients received treatment for 3 months. Suspected bleeding events were assessed by a blinded adjudication committee.

Results

Primary Endpoint(s)

- The composite of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was 3%, 7.8%, 3.8%, 10.6%, and 3.2% for patients receiving edoxaban 30 mg once daily, 30 mg twice daily,

60 mg once daily, 60 mg twice daily, and warfarin, respectively (statistics not provided).- Compared with warfarin, the composite of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was significantly higher with edoxaban 30 and 60 mg taken twice daily.

- For patients receiving edoxaban 30 or 60 mg once daily, the rate of major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was similar to that of warfarin.

- The proportion of patients with elevated

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at least 3 times the upper limit of normal was 1.3%, 0.9%, 3.1%, 1.7%, and 1.6% for patients receiving edoxaban 30 mg once daily, 30 mg twice daily, 60 mg once daily, 60 mg twice daily, and warfarin, respectively. There were no differences among treatment groups (statistics not provided).

Secondary Endpoint(s)

Stroke occurred in 1, 2, 1, 1, and 3 patients receiving edoxaban 30 mg once daily, 30 mg twice daily, 60 mg once daily, 60 mg twice daily, and warfarin, respectively.

Comments: The edoxaban 60 mg twice-daily arm was discontinued based on a recommendation from the Data Safety and Monitoring Board. The time in therapeutic range (INR of 2 to 3) with warfarin was 49.7% after week 6, and time within the extended therapeutic range (INR of 1.8 to 3.2) was 63.9% after week 6. The rate of bleeding for edoxaban 30 and 60 mg when dosed once daily was similar to warfarin.

Limitations: The study included a small cohort, had a short duration of follow-up, and was not designed to assess efficacy outcomes. In the warfarin group, goals for time within therapeutic INR range were not met.

Indication: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Hip or Total Knee Arthroplasty

Guidelines

Guideline: Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines

Reference: Falck-Ytter Y, et al, 201243

Comments: The guideline advocates use of LMWH therapy, fondaparinux, dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, low-dose unfractionated heparin, dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonist therapy, or aspirin for a minimum of 10 to 14 days after hip or total knee arthroplasty as opposed to no antithrombotic prophylaxis. Edoxaban was not addressed in the guidelines.

Studies

Drug: Edoxaban vs Enoxaparin

Reference: Fuji T, et al, 2011 (STARS E-III and STARS J-V studies)4

Study Design: Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group, international studies

Study Funding: Daiichi-Sankyo

Patients: 1,307 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty. Patients were native to Japan or Taiwan. There were no clinically relevant differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups.

Intervention: Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban 30 mg once daily (initiated 6 to 24 hours after surgery) or enoxaparin 2,000 units twice daily (initiated 24 to 36 hours after surgery) for 11 to 14 days.

Results

Primary Endpoint(s)

- The composite of symptomatic and asymptomatic DVT and PE was 5.1% for edoxaban-treated patients and 10.7% for enoxaparin-treated patients, with a relative risk reduction of 52.7% (P < .001 for superiority) and the number needed to treat (NNT) of 17.9.

Secondary Endpoint(s)

- Principal safety outcome was the composite of clinically relevant major and nonmajor bleeding: 4.6% for edoxaban-treated patients and 3.7% for enoxaparin-treated patients (P = .427).

Comments: This was a phase 2 study. Edoxaban 30 mg once daily was superior to enoxaparin 2,000 units twice daily in the prevention of VTE following total knee arthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty and did not increase the incidence of bleeding.

Limitations: The study included a Japanese and Taiwanese cohort with no patients in the United States. Results were only available as a meeting abstract.

Drug: Edoxaban vs Dalteparin

Reference: Raskob G, et al, 20106

Study Design: Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group, multicenter, international study

Study Funding: Daiichi-Sankyo

Patients: 903 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty; approximately 48.8% were from the Ukraine, 29.6% were from Russia, 9.4% were from the United States, 7.5% were from Canada, and 4.2% were from Latvia. Baseline demographics were similar among groups; approximate mean age was 58 years, 40% were male, 98% of patients were White, and 1% were Black.

Intervention: Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio to receive edoxaban 15, 30, 60, or 90 mg once daily or dalteparin 2,500 units followed by 5,000 units once daily. Both drugs were given 6 to 8 hours postoperatively and were continued for 7 to 10 days.

Results

Primary Endpoint(s)

- The rates of VTE during the 7- to 10-day treatment period assessed by venography were 28.2% (P = .005), 21.2% (P < .001), 15.2% (P < .001), and 10.6% (P < .001) for patients receiving edoxaban 15, 30, 60, and 90 mg, respectively, compared with 43.8% in the dalteparin group. The NNT was 6.4 with edoxaban 15 mg, 4.4 with edoxaban 30 mg, 3.5 with edoxaban 60 mg, and 3.1 with edoxaban 90 mg.

Secondary Endpoint(s)

- The incidence rates of major VTE were 6.5% (P = .036), 3.3% (P = .001), 1.9% (P < .001), and 1.3% (P < .001) for patients receiving edoxaban 15, 30, 60, and 90 mg, respectively, compared with 13.9% in the dalteparin group.

- The incidence rates of proximal DVT were 6.5% (P = .036), 3.3% (P = .001), 1.3% (P < .001), and 1.3% (P < .001) for patients receiving edoxaban 15, 30, 60, and 90 mg, respectively, compared with 13.9% in the dalteparin group.

- There were 4 deaths during the study: 1 death (myocardial infarction) in the edoxaban 15 mg group and 3 deaths (2 from cardiopulmonary insufficiency and 1 from bilateral pneumonia) in the edoxaban 30 mg group.

- The principle safety outcome, the composite of clinically relevant major and nonmajor bleeding, occurred in 1.6%, 1.8%, 2.2%, and 2.3% of patients treated with edoxaban 15, 30, 60, and 90 mg, respectively, and in 0% of patients treated with dalteparin.

Comments: This was a phase 2 study. The study was designed to have 150 evaluable patients per group. There were 170, 151, 158, and 151 patients in the edoxaban 15, 30, 60, and 90 mg efficacy analysis set, respectively, and 144 patients in the dalteparin group. All studied edoxaban doses were more effective at reducing the incidence of VTE 7 to 10 days postoperation compared with dalteparin. The incidence of bleeding was similar among edoxaban-treated patients. Constipation, nausea, and pyrexia occurred more frequently in patients treated with edoxaban.

Limitations: The primary outcome of total VTE occurred at a higher rate than the assumed 15% incidence in the dalteparin-treated patients used in the sample size calculations. The study population consisted of a small North American cohort.

CONTRAINDICATIONS, WARNINGS, AND PRECAUTIONS

Contraindications

Edoxaban is contraindicated in patients with active pathological bleeding.1

Hypersensitivity reactions (eg, anaphylactic reactions) to edoxaban or any product ingredients (mannitol, pregelatinized starch, crospovidone, hydroxypropyl cellulose, magnesium stearate, talc, carnauba wax, dyes) should also be considered a contraindication of edoxaban therapy.1

Warnings and Precautions

Patients with nonvalvular AF and a CrCl above 95 mL/min should be treated with another anticoagulant [boxed warning]. The ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 study reported an increased rate of ischemic stroke in the group treated with edoxaban 60 mg compared with those treated with warfarin. This difference is believed to be due to increased edoxaban clearance in patients with CrCl above 95 mL/min.1

Premature discontinuation of edoxaban therapy may increase the risk of ischemic events (eg, stroke) in patients with atrial fibrillation [boxed warning]. If edoxaban therapy is discontinued for a reason other than pathological bleeding or completion of therapy, coverage with another anticoagulant should be

considered.1

Epidural or spinal procedures (eg, neuraxial anesthesia, spinal puncture) can result in epidural or spinal hematomas [boxed warning]. Factors that can increase this risk include use of an indwelling epidural catheter, concomitant use with other drugs that affect hemostasis (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], platelet inhibitors, other anticoagulants), history of traumatic or repeated epidural or spinal punctures, history of spinal deformity or spinal surgery, or unknown optimal timing between the administration of edoxaban and neuraxial procedures. All patients should be monitored for signs and symptoms of neurological impairment (eg, numbness or weakness of the legs, bowel, or bladder dysfunction) and treated, if necessary.1

Bleeding is a potential adverse effect of all anticoagulants. Risk of bleeding is increased when the anticoagulant is used concomitantly with other drugs that affect hemostasis (eg, aspirin, antiplatelet drugs, NSAIDs, fibrinolytic therapy).1

There is no established way to reverse the anticoagulant effect of edoxaban. However, anti-inhibitor coagulant complex, prothrombin complex concentrate, 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate, or recombinant factor VIIa may be able to reverse the effects of edoxaban.44-46 Therefore, any of these hemostatic agents may be useful as a potential edoxaban-reversing agent.

In patients with renal impairment, edoxaban clearance is reduced. Use caution and monitor for bleeding in patients with renal impairment. Patients with moderate renal impairment (CrCl 15 to 50 mL/min) should receive a reduced edoxaban dose.1,16,17,28,35 Edoxaban has not been studied in patients with severe renal dysfunction (CrCl less than 15 mL/min). Edoxaban probably should be not used in this population due to an increased risk of bleeding.16,17,28,35

Patients with low body weight (less than 60 kg) may be at an increased risk of bleeding and may require a lower edoxaban dose.1,16,35,41

The safety and efficacy of edoxaban have not been studied in patients with mechanical heart valves or moderate to severe mitral stenosis.1,35 Edoxaban therapy is not recommended for these patients.1

Edoxaban is classified as Pregnancy Category C. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women; the drug should be used with caution.1 In clinical trials, there were 6 live births (4 full term, 2 preterm), 1 first-trimester spontaneous abortion, and 3 cases of elective termination of pregnancy. In studies in rats and rabbits, no teratogenic effects were observed. However, there were cases of absent or small fetal gallbladder, increased postimplantation loss, increased spontaneous abortion, and decreased live fetuses and fetal weight.1

The amount excreted in human milk is unknown. Edoxaban is detected in the milk of lactating rats; caution is advised.1

Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients have not been established.1

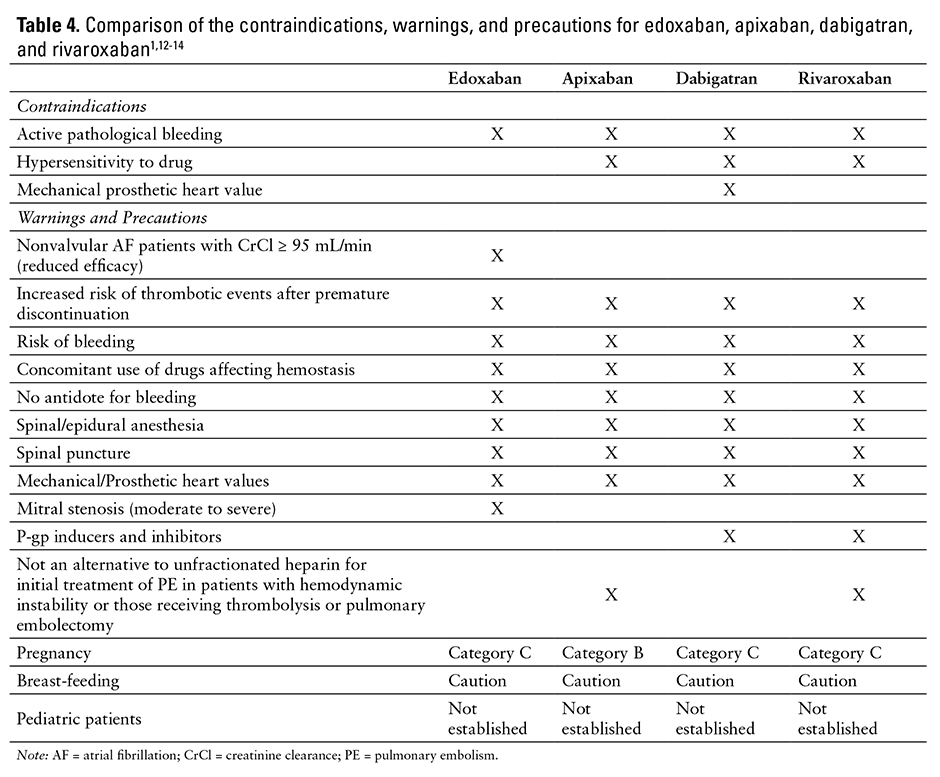

See Table 4 for a comparison of the contraindications, warnings, and precautions associated with edoxaban, apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban therapy.1,12-14

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most common adverse reactions reported in patients treated for nonvalvular AF were bleeding and anemia. Bleeding led to discontinuation in 3.9% of patients treated with edoxaban and 4.1% of patients treated with warfarin for nonvalvular AF. The most common adverse reactions in patients with DVT or PE were bleeding, rash, abnormal liver function tests, and anemia; bleeding led to discontinuation in 1.4% of patients treated with edoxaban and 1.4% of patients treated with warfarin.1

In patients with nonvalvular AF, major bleeding occurred in 3.1% of patients in the edoxaban group and 3.7% of patients in the warfarin group (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.97). A higher rate of GI bleeding was observed with edoxaban than warfarin in nonvalvular AF patients with a CrCl of 95 of mL/min or less: 1.8% with edoxaban, and 1.3% with warfarin (HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.73). All other bleeding events had a lower rate with edoxaban compared with warfarin therapy (HR of 0.44 for intracranial bleeding [95% CI, 0.32 to 0.61], HR of 0.49 for hemorrhagic stroke [95% CI, 0.32 to 0.74], HR of 0.37 for other intracranial hemorrhage [95% CI, 0.22 to 0.62], HR of 0.51 for fatal bleeding [95% CI, 0.3 to 0.86], HR of 0.54 for fatal bleeding from intracranial hemorrhage [95% CI, 0.31 to 0.94], and HR of 0.87 for clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding [95% CI, 0.8 to 0.95]).1 The risk of bleeding was increased in patients receiving aspirin, patients older than 75 years, and those with decreased renal function.1 In patients with DVT or PE, clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 8.5% of the edoxaban group and 10.3% of the warfarin group (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.94; P = 0.004). Major bleeding occurred in 1.4% of the edoxaban group and 1.6% of the warfarin group.1

Anemia-related adverse events in patients with nonvalvular AF occurred in 9.6% of those treated with edoxaban 60 mg and 6.8% of those treated with warfarin. In patients treated for DVT or PE, anemia-related adverse events occurred in 1.7% of those treated with edoxaban 60 mg and 1.3% of those treated with warfarin.1

Rash in patients with nonvalvular AF occurred in 4.2% of those treated with edoxaban 60 mg and 4.1% of those treated with warfarin. In patients treated for DVT or PE, rash occurred in 3.6% of those treated with edoxaban 60 mg and 3.7% of those treated with warfarin.1

Abnormal liver function tests in patients with nonvalvular AF occurred in 4.8% of those treated with edoxaban 60 mg and 4.6% of those treated with warfarin. Abnormal liver function tests in patients with DVT or PE occurred in 7.8% of those treated with edoxaban 60 mg and 7.8% of those treated with warfarin.1

DRUG INTERACTIONS

Coadministration of strong P-gp inhibitors (eg, quinidine, verapamil, ketoconazole, amiodarone, dronedarone, cyclosporine, erythromycin) increased edoxaban exposure. A modest or minimal increase in edoxaban exposure was observed for quinidine, verapamil, ketoconazole, amiodarone, dronedarone, cyclosporine, erythromycin, and digoxin.1,19,25,27 No clinically significant changes in pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, or renal elimination were observed with coadministration of edoxaban with digoxin, atorvastatin, esomeprazole, naproxen, or aspirin.1,19 Increases in edoxaban exposure may result in increased bleeding risk. The edoxaban dose should be reduced in patients treated for DVT or PE and taking strong P-gp inhibitors concomitantly.1,6,16

Edoxaban pharmacokinetics were not affected by concomitant low-dose aspirin (up to 100 mg) or naproxen; however, high-dose aspirin increased systemic exposure of edoxaban by approximately 30%.47,48

Administration of edoxaban 24 hours after warfarin cessation resulted in an increase in mean INR 2 hours after dosing (from 2.31 to 3.84). The increase is transient and returned to baseline 12 hours after dosing. Edoxaban administered 24 hours after warfarin cessation was safe and well tolerated.49 Administration of edoxaban 12 hours after a single dose of enoxaparin had no effect on the pharmacokinetics of either drug.30

Coadministration with anticoagulants, NSAIDs, aspirin, other antiplatelet aggregation inhibitors, and thrombolytics may increase the risk of bleeding.1

RECOMMENDED MONITORING

Anticipated monitoring for edoxaban includes periodic evaluation for signs and symptoms of bleeding, such as a drop in hemoglobin and/or hematocrit and positive stool occult blood tests. Periodically assess serum creatinine and renal function in patients receiving edoxaban because adjustment in dose may be required in patients with moderate renal impairment.16,35

DOSING

The recommended dose of edoxaban for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular AF is based on the patient’s CrCl. If CrCl is greater than 50 mL/min up to 95 mL/min, the recommended dose is 60 mg once daily. If CrCl is between 15 and 50 mL/min, the recommended dose is 30 mg once daily.1 If CrCl is greater than 95 mL/min, another drug should be selected.1

The recommended dose of edoxaban for the treatment of DVT is 60 mg once daily after the patient has received 5 to 10 days of parenteral anticoagulant. If CrCl is 15 to 50 mL/min or body weight is 60 kg or less, or if the patient requires treatment with certain P-gp inhibitors, the recommended dose is 30 mg once daily.1

Patients with mild hepatic impairment require no dose adjustment. Edoxaban should be avoided in patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment because of the potential for intrinsic coagulation abnormalities.1

The tablets should be administered by mouth without regard to meals.1 There are no data on the effects on edoxaban bioavailability of crushing tablets, mixing tablets into food or liquids, or administering tablets through feeding tubes.1

The 15 mg tablets should only be used to transition a patient from edoxaban to warfarin.1

If surgery or other interventions are required, edoxaban should be discontinued at least 24 hours prior to the procedure to decrease the risk of bleeding.1 Edoxaban therapy should be restarted after the procedure as soon as adequate hemostasis is achieved. Onset of action for edoxaban is 1 to 2 hours. If unable to take oral medications, the patient should be started on a parenteral anticoagulant and then switched to edoxaban when oral therapy is possible.1

Recommendations for switching from another anticoagulant to edoxaban vary by agent. If the patient is switched from warfarin or other vitamin K

antagonists, the first anticoagulant should be discontinued and edoxaban started when INR is 2.5 or less. If the patient is switched from an oral anticoagulant other than warfarin or other vitamin K antagonists, the first anticoagulant should be discontinued and edoxaban started at the time of the next scheduled dose. If the patient is switched from an LMWH, the LMWH should be discontinued and edoxaban started at the time of the next scheduled dose. If the patient is switched from unfractionated heparin, the heparin infusion should be discontinued and edoxaban started 4 hours later.1

Recommendations for switching from edoxaban to another anticoagulant vary by agent. If the patient is switched from edoxaban to warfarin or other vitamin K antagonists, edoxaban should be tapered and warfarin started; patients treated with edoxaban 60 mg should have their dose reduced to edoxaban 30 mg and started on warfarin therapy, and patients treated with edoxaban 30 mg should have their dose reduced to edoxaban 15 mg and started on warfarin therapy. An INR would

then be obtained at least weekly, just prior to edoxaban dosing, and once the INR is 2 or higher, edoxaban can be discontinued and the patient treated with warfarin alone. Alternatively, edoxaban therapy can be replaced with a parenteral anticoagulant and oral warfarin, and the parenteral anticoagulant can be discontinued when the INR is 2 or higher. If the patient is switched from edoxaban to an oral anticoagulant other than warfarin or other vitamin K antagonists, edoxaban should be discontinued and the other anticoagulant started at the time of the next scheduled edoxaban dose. If the patient is switched from edoxaban to a parenteral anticoagulant, edoxaban should be discontinued and the parenteral anticoagulant started at the time of the next scheduled edoxaban dose.1

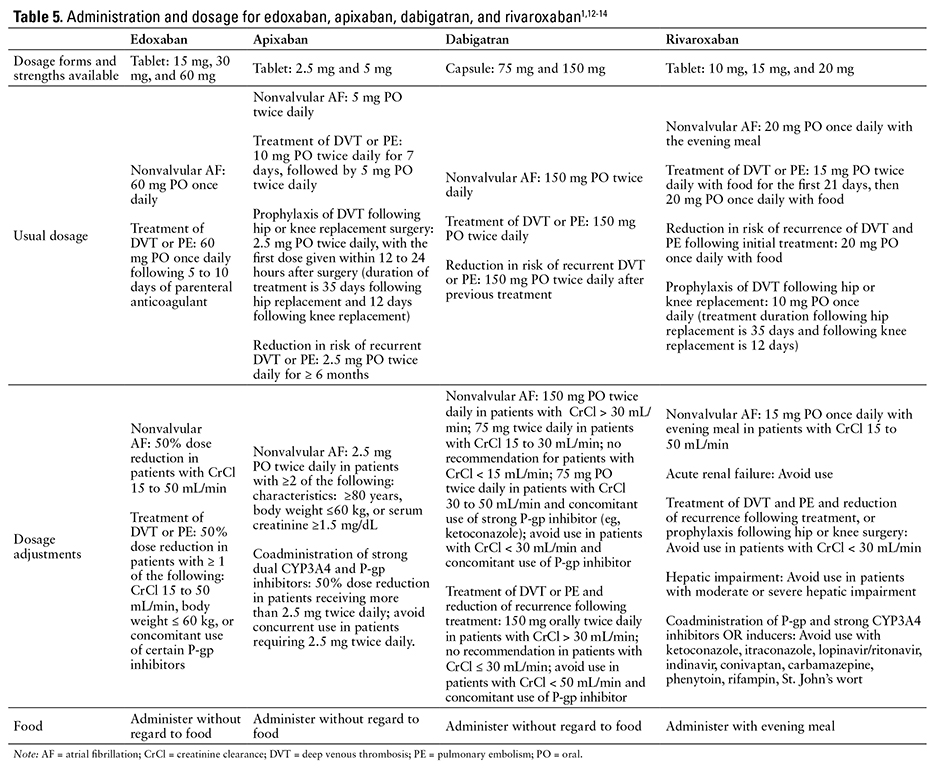

The recommended dosing and administration of apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban are compared in Table 5.1,12-14

PRODUCT AVAILABILITY

Edoxaban was approved on January 8, 2015.50 It is available as a 15 mg, 30 mg, and 60 mg tablet. The 15 mg strength is available in bottles of 30. The 30 and 60 mg strengths are available in bottles of 30, 90, and 500, and in 10 blister cards of 10 and 5 blister cards of 10. The drug should be stored at 20°C to 25°C (68°F to 77°F), with excursions permitted to 15°C to 30°C (59°F to 86°F).1

DRUG SAFETY/RISK EVALUATION AND MITIGATION STRATEGY (REMS)

No REMS is required for edoxaban.50

CONCLUSION

Edoxaban is the third oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor to be approved in the United States. Edoxaban is dosed without regard to meals and is only metabolized by CYP3A4 to a minor extent, resulting in fewer drug-drug interactions compared with apixaban and rivaroxaban. Edoxaban, like apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban, requires dosage adjustment in patients with renal impairment, low body weight, or concurrent use of strong P-gp inhibitors. In phase 3 clinical trials, edoxaban was noninferior to warfarin for the treatment and prevention of recurrence of VTE and for the prevention of stroke or systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular AF. All doses of edoxaban were associated with lower rates of major bleeding, clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, and any bleeding for each indication and were associated with reduced death from cardiovascular causes in patients with nonvalvular AF. The duration of action of edoxaban is dependent on its half-life and not the half-life of the affected clotting factors; therefore, the onset of action will be quicker than warfarin, but in patients with a history of poor adherence, there may be periods during which they are unprotected from blood clots. Like the other direct factor Xa inhibitors, there is no antidote. If the patient experiences an adverse bleeding event, the only method of treatment is interruption of therapy.

REFERENCES

- Savaysa (edoxaban) [prescribing information]. Parsippany, NJ: Daiichi Sankyo Co; January 2015.

- Edoxaban. ClinicalTrials.gov Web site. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- Fuji T, Wang C-J, Fujita S, Tachibana S, Kawai Y. Edoxaban in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: A phase IIb dose-finding study [abstract]. Blood. 2009;114(22):2098.

- Fuji T, Wang C-J, Fujita S, et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total knee or hip arthroplasty: A pooled analysis of two pivotal studies vs. enoxaparin [abstract]. Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(suppl 2):109.

- Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al; ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 Investigators. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):

2093-2104. - Raskob G, Cohen AT, Eriksson BI, et al. Oral direct factor Xa inhibition with edoxaban for thromboprophylaxis after elective total hip replacement. A randomised double-blind dose-response study. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(3):

642-649. - Fuji T, Fujita S, Kawai Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of edoxaban in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Thromb Res. 2014;133(6):1016-1022.

- Fuji T, Wang CJ, Fujita S, Kawai Y, Kimura T, Tachibana S. Safety and efficacy of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, for thromboprophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty in Japan and Taiwan. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(12):2439-2446.

- Fuji T, Wang CJ, Fujita S, et al. Safety and efficacy of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty: The STARS E-3 trial. Thromb Res. 2014;134(6):1198-1204.

- Bounameaux H, Camm AJ. Edoxaban: An update on the new oral direct factor Xa inhibitor [published correction appears in Drugs. 2014;74(12):1455]. Drugs. 2014;74(11):1209-1231.

- Piazza G, Mani V, Grosso M, et al. A randomized, open-label, multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of edoxaban monotherapy versus low-molecular weight heparin/warfarin in patients with symptomatic deep vein thrombosis—edoxaban thrombus reduction imaging study (eTRIS) [abstract]. Circulation. 2014;130:A12074.

- Eliquis (apixaban) [prescribing information]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; August 2014.

- Xarelto (rivaroxaban) [prescribing information]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc; January 2015.

- Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate) [prescribing information]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc; January 2015.

- Partida RA, Giugliano RP. Edoxaban: Pharmacological principles, preclinical and early-phase clinical testing. Future Cardiol. 2011;7(4):459-470.

- Büller HR, Décousus H, Grosso MA, et al; Hokusai-VTE Investigators. Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):390]. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1406-1415.

- Bathala MS, Masumoto H, Oguma T, He L, Lowrie C, Mendell J. Pharmacokinetics, biotransformation, and mass balance of edoxaban, a selective, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(12):2250–2255.

- Stambler BS. A new era of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: Comparing a new generation of oral anticoagulants with warfarin. Int Arch Med. 2013;6(1):46.

- Mendell J, Noveck RJ, Shi M. Pharmacokinetics of the direct factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban and digoxin administered alone and in combination. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2012;60(4):335-341.

- Samama MM, Mendell J, Guinet C, Le Flem L, Kunitada S. In vitro study of the anticoagulant effects of edoxaban and its effect on thrombin generation in comparison to fondaparinux. Thromb Res. 2012;129(4):e77-e82.

- Samama MM, Kunitada S, Oursin A, Depasse F, Heptinstall S. Comparison of a direct factor Xa inhibitor, edoxaban, with dalteparin and ximelagatran: A randomised controlled trial in healthy elderly adults. Thromb Res. 2010;126(4):e286-e293.

- Parasrampuria DA, Marbury T, Matsushima N, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of edoxaban in end-stage renal disease subjects undergoing haemodialysis. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(3).

- Ogata K, Mendell-Harary J, Tachibana M, et al. Clinical safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(7):743-753.

- Mendel J, Zahir H, Ridout G, et al. Drug-drug interaction studies of cardiovascular drugs (amiodarone, digoxin, quinidine, atorvastatin and verapamil) involving P-glycoprotein (P-GP), and efflux transporter, on the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor. JACC. 2011;57(suppl):E1510.

- Mendell J, Tachibana M, Shi M, Kunitada S. Effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of edoxaban, an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(5):687-694.

- Yin OQ, Miller R. Population pharmacokinetics and dose-exposure proportionality of edoxaban in healthy volunteers. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(10):743-752.

- Mendell J, Zahir H, Matsushima N, et al. Drug-drug interaction studies of cardiovascular drugs involving P-glycoprotein, an efflux transporter, on the pharmacokinetics of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013;13(5):331-342.

- Ridout G, de la Motte S, Niemczyk S, et al. Effect of renal function on edoxaban pharmacokinetics (PK) and on population PK/PK-PD model [abstract]. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49(9):1124.

- Masumoto H, Yoshigae Y, Watanabe K, Takakusa H, Okazaki O, Izumi T. In vitro metabolism of edoxaban and the enzymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of edoxaban [abstract]. AAPS J. 2010;12(suppl 2):W4308.

- Zahir H, Matsushima N, Halim AB, et al. Edoxaban administration following enoxaparin: a pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, and tolerability assessment in human subjects. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(1):166-175.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012;142(6):1698-1704]. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):

e419S-e494S. - Furie KL, Goldstein LB, Albers GW, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Oral antithrombotic agents for the prevention of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A science advisory for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43(12):

3442-3453. - January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):2305-2307]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):e1-e76.

- Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Rost NS, et al; ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 Investigators. Cerebrovascular events in 21105 patients with atrial fibrillation randomized to edoxaban versus warfarin: Effective anticoagulation with factor Xa next generation in atrial fibrillation-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 48. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2372-2378.

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Antman EM, et al. Evaluation of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: Design and rationale for the Effective aNticoaGulation with factor xA next GEneration in Atrial Fibrillation-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48). Am Heart J. 2010;160(4):635-641.

- Global Study to Assess the Safety and Effectiveness of Edoxaban (DU-176b) vs standard practice of dosing with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation (EngageAFTIMI48). ClinicalTrials.gov Web site. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00781391. Updated September 9, 2014. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Kato ET, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban for the management of elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: Engage AF-TIMI 48 trial [abstract]. Circulation. 2014;130:A16612.

- Magnani G, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: Insights from Engage

AF-TIMI 48 [abstract]. Circulation. 2014;130:A12680. - Geller BJ, Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, et al. Systemic, non-cerebral, arterial embolism in 21,105 patients with atrial fibrillation randomized to edoxaban or warfarin: Results from the Engage AF-TIMI 48 trial [abstract]. Circulation. 2014;130:A18597.

- Xu H, Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, et al. Concomitant use of antiplatelet therapy with edoxaban or warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation in the Engage AF-TIMI 48 trial [abstract]. Circulation. 2014;130:A19119.

- Chung N, Jeon HK, Lien LM, et al. Safety of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, in Asian patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(3):535-544.

- Weitz JI, Connolly SJ, Patel I, et al. Randomised, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational phase 2 study comparing edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, with warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(3):633-641.

- Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e278S-e325S.

- Morishima Y, Honda Y, Shibano T. Anti-inhibitor

coagulant complex, prothrombin complex concentrate, and recombinant factor VIIa reverse prothrombin time prolonged by edoxaban in human plasma [abstract]. Blood. 2010;116(21):3319. - Zahir H, Brown KS, Vandell AG, et al. Edoxaban effects on bleeding following punch biopsy and reversal by a 4-factor

prothrombin complex concentrate [published correction appears in Circulation. 2015;131(1):e10]. Circulation. 2015;131(1):82-90. - Lip GY, Agnelli G. Edoxaban: A focused review of its clinical pharmacology. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(28):

1844-1855. - Mendell-Harary J, Len F, Chen S, et al. Effect of low-dose aspirin on the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor [abstract]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(suppl 1):S63.

- Mendell J, Lee F, Chen S, Worland V, Shi M, Samama MM. The effects of the antiplatelet agents, aspirin and naproxen, on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the anticoagulant edoxaban, a direct factor Xa inhibitor. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;62(2):212-221.

- Mendell J, Noveck RJ, Shi M. A randomized trial of the safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, following a switch from warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(4):966-978.

- Temple R. NDA approval letter: Savaysa (edoxaban tosylate NDA 206316). US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/206316Orig1s000ltr.pdf. Published January 8, 2015. Accessed January 14, 2015.

*Founder and Contributing Editor, The Formulary; †Director, Drug Information Center, and Professor of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, Washington State University Spokane; ‡Drug Information Resident, College of Pharmacy, Washington State University Spokane. The authors indicate no relationships that could be perceived as a conflict of interest.