Cardiovascular Therapeutics

Reversal Strategies for Intracranial Hemorrhages in Patients Taking Oral Factor Xa Inhibitors

Betsy Karli, PharmD*; Billie Bartel, PharmD†; and Rachel Pavelko, PharmD‡

Cardiovascular Therapeutics

Reversal Strategies for Intracranial Hemorrhages in Patients Taking Oral Factor Xa Inhibitors

Betsy Karli, PharmD*; Billie Bartel, PharmD†; and Rachel Pavelko, PharmD‡

Cardiovascular Therapeutics

Reversal Strategies for Intracranial Hemorrhages in Patients Taking Oral Factor Xa Inhibitors

Betsy Karli, PharmD*; Billie Bartel, PharmD†; and Rachel Pavelko, PharmD‡

Factor Xa (fXa) inhibitors are becoming more common in clinical practice due to a variety of reasons. Unfortunately, limited data are currently available on the safe and efficacious reversal of these agents. This series presents 3 patient cases of intracranial hemorrhage and illustrates the observed effect of different methodologies undertaken in an attempt to reverse the fXa inhibitors implicated. Additionally, a brief review of the current available literature in reversal strategies is provided. The appropriate reversal for fXa inhibitors at this time is unknown. The cases described indicate that the administration of fresh frozen plasma and 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate may provide minimal benefit in reversing the coagulation abnormalities caused by fXa inhibitors. However, in a life-threatening situation, the addition of these agents should be considered to prevent further progression of the bleed.

Factor Xa (fXa) inhibitors are becoming more common in clinical practice due to a variety of reasons. Unfortunately, limited data are currently available on the safe and efficacious reversal of these agents. This series presents 3 patient cases of intracranial hemorrhage and illustrates the observed effect of different methodologies undertaken in an attempt to reverse the fXa inhibitors implicated. Additionally, a brief review of the current available literature in reversal strategies is provided. The appropriate reversal for fXa inhibitors at this time is unknown. The cases described indicate that the administration of fresh frozen plasma and 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate may provide minimal benefit in reversing the coagulation abnormalities caused by fXa inhibitors. However, in a life-threatening situation, the addition of these agents should be considered to prevent further progression of the bleed.

Factor Xa (fXa) inhibitors are becoming more common in clinical practice due to a variety of reasons. Unfortunately, limited data are currently available on the safe and efficacious reversal of these agents. This series presents 3 patient cases of intracranial hemorrhage and illustrates the observed effect of different methodologies undertaken in an attempt to reverse the fXa inhibitors implicated. Additionally, a brief review of the current available literature in reversal strategies is provided. The appropriate reversal for fXa inhibitors at this time is unknown. The cases described indicate that the administration of fresh frozen plasma and 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate may provide minimal benefit in reversing the coagulation abnormalities caused by fXa inhibitors. However, in a life-threatening situation, the addition of these agents should be considered to prevent further progression of the bleed.

Hosp Pharm 2015;50(7):569–577

2015 © Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.

doi: 10.1310/hpj5007-569

In the past decade, the introduction of novel anticoagulants has provided new options to physicians and patients for the prevention of thromboembolic diseases. Warfarin was the only oral medication available for over 50 years. Warfarin has marked limitations, including frequent monitoring, numerous drug-drug and drug-dietary interactions, slow onset of action, and narrow therapeutic window.1 These limitations have led to the development of new oral anticoagulants. Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban are oral factor Xa (fXa) inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF), postoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT), thromboprophylaxis, and DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) treatment.2,3

Many of the limitations associated with warfarin are overcome by fXa inhibitors. In clinical trials, fXa inhibitors were associated with decreased rates of intracranial hemorrhage in comparison to warfarin.4,5 A reduction in hemorrhagic complications and attractive pharmacokinetics has led to increased prescribing by practitioners.

A major limitation to fXa inhibitors is their inability to quickly and successfully reverse the effect of anticoagulation in an acute life-threatening hemorrhage. As prescribing of these agents increases, hemorrhagic events are likely to become more common. Minimal guidance is available on the safe and efficacious reversal of these agents. Research is ongoing in an attempt to find an effective reversal agent.6 This series presents 3 patient cases of intracranial hemorrhage and illustrates the observed effect of different methodologies undertaken in an attempt to reverse the fXa inhibitors implicated.

CASE 1

A 72-year-old male presented to a rural emergency department (ED) at approximately 1600 complaining of headache to the right temporal parietal area, dizziness, unsteadiness, and difficulty forming thoughts. The onset of symptoms began 13 hours prior to ED admission. The patient had a history of paroxysmal AF/flutter, coronary artery disease (CAD) with stent placement 4 months prior, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and osteoarthritis. His home medications included rivaroxaban 20 mg daily (last dose was taken 25 hours prior to presentation), aspirin 81 mg daily, amiodarone, metoprolol, pravastatin, and inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators.

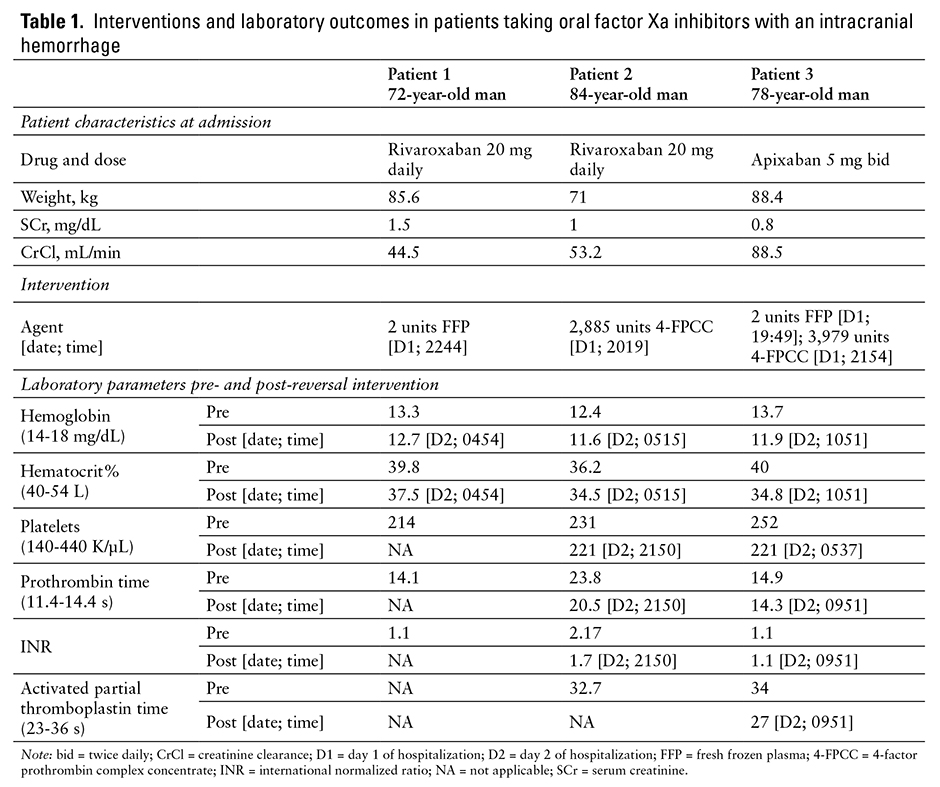

The initial neurologic examination showed sluggish extraocular movements and some loss of visual field to the lateral right and inner upper left eye. Head CT showed an acute 3.5 cm intraparenchymal hematoma at the junction of occipital and parietal lobes with localized mass effect and no significant midline shift. EKG showed a sinus arrhythmia, and vital signs were stable. Hematologic labs upon presentation are listed in Table 1, and serum creatinine was 1.5, which is elevated from the patient’s baseline of 1.0. The patient received fluids and was transferred to the tertiary care hospital. He arrived 3.5 hours after initial presentation to the rural ED.

Upon hospital admission, the patient received 2 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) at 2244. No surgical intervention was performed. Hematologic labs after FFP administration are listed in Table 1; however prothrombin time (PT)/international normalized ratio (INR) was not rechecked after FFP was given or again during the patient’s hospital stay. On day 2 of hospitalization, the patient had an MRI at 1100, approximately 12 hours after administration of FFP. It showed no change in hematoma size or degree of mass effect and had no findings to suggest underlying causes of bleeding including neoplasm, vascular malformation, or ischemic infarct with hemorrhagic transformation. Neurologic exam was stable and serum creatinine improved to 1.3. On day 3, the patient was noted to have increased confusion and disorientation; he experienced a witnessed 45-second seizure, after which he was aphasic. A repeat head CT showed no change in hematoma size or mass effect. The patient was treated with antiepileptics and had no seizure recurrence. A dexamethasone taper was started for cerebral edema. On day 4, the patient’s confusion, disorientation, and aphasia had improved, and he was discharged to inpatient rehabilitation with some slowness of thought and actions, mild gait instability, and the need for minimal assistance with activities of daily living. After 10 days in rehab, the patient was discharged to home and anticoagulation was not resumed.

CASE 2

An 84-year-old male presented to a rural ED at approximately 1700 via ambulance due to acute onset of neurological deficits including difficulty speaking and confusion. A stat head CT was obtained and showed a large left-sided intracerebral hemorrhage measuring 7.3 cm x 5.2 cm. The patient was intubated and transferred to Avera McKennan Hospital via ambulance for further evaluation and care. The patient’s past medical history included AF, recent DVT/PE, COPD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and CAD. He was taking rivaroxaban 20 mg daily (timing of last dose unknown), aspirin 81 mg daily, amiodarone, simvastatin, carvedilol, and an inhaled anticholinergic.

The patient was directly admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and initial neurologic exam showed some withdrawal to pain on the left side, upper extremity posturing, facial weakness on the right side, increased deep tendon reflexes, and a Babinski sign on the right. According to neurosurgery, the patient was not a surgical candidate due to his recent use of rivaroxaban. Baseline pertinent labs are shown in Table 1. The patient had a normal EKG and was hypertensive with a blood pressure of 190/96 mm Hg. He received 2,885 units of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentration (4-FPCC) at 2019, which was approximately 39 IU/kg. A lower dose than planned was given, because the hospital had an insufficient supply of available medication. The patient was started on a nicardipine infusion and intravenous pushes of hydralazine to maintain systolic blood pressures between 150 and 165 mm Hg. After administration of 4-FPCC, the patient’s coagulation abnormality was not fully reversed, which is evident by the repeat labs shown in Table 1.

On day 2 at 0900, a repeat CT without contrast was completed approximately 9.5 hours after 4-FPCC administration. The CT revealed an enlarged intraparenchymal hematoma measuring 8.9 cm x 6.5 cm with evidence of an increase in edema and midline shift. Additionally, more blood was noted in the ventricles and subarachnoid space. Neurologically the patient only responded to localized pain and was noted to have nonpurposeful movements while on no sedative or analgesic medications. The patient spiked a fever of 101.3°F and was started on piperacillin/tazobactam for possible aspiration pneumonia.

Over the next few days, the patient’s status varied insignificantly. He remained intubated with ventilator support and neurologically showed no improvement. On day 5 of hospitalization, the patient’s home medications of carvedilol and amiodarone were restarted for blood pressure and heart rate control. On day 6, piperacillin/tazobactam was de-escalated to ceftriaxone to complete a 7-day course of antibiotic therapy. Ventilator support was withdrawn on day 11, and the patient expired approximately 8 hours later.

CASE 3

A 78-year-old male was seen in the ED at 1700 with complaints of an acute worsening headache, right facial droop, slurring of speech, and acute confusion since approximately 1300. The patient had fallen about a week before and sustained trauma to his head, but did not seek medical attention at that time.

Past medical history was significant for ischemic stroke 8 months prior, diabetes mellitus type II, benign prostatic hyperplasia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Pertinent home medications included apixaban 5 mg twice daily (last reported dose was morning of admission), amlodipine, pravastatin, dexlansoprazole, dutaseteride-tamsulosin, lisinopril, loratidine, and glipizide-metformin.

The patient’s initial neurologic exam revealed that the patient was awake but lethargic and not orientated to person, place, or time. The patient also had some receptive aphasia. The disorientation did improve within approximately 2 hours of presentation. The patient had a stat head CT at 1704, which revealed a subdural hematoma measuring about 1.7 cm at the thickest area and a subfacline shift to the right measuring approximately 8 to 9 mm. It was determined that there was likely a chronic subdural hematoma with more recent acute intracranial hemorrhage. The patient had an EKG that showed sinus rhythmand all vital signs were normal. -Baseline pertinent labs are found in Table 1. At 1949, the patient received 2 units of FFP followed by 3,979 units of 4-FPCC at 2154, which was approximately 45 IU/kg. The 4-FPCC dose was rounded to nearest vial size in accordance with hospital procedure. The patient was transferred to the ICU and started on seizure prophylaxis with levetiracetam and 1.5% sodium chloride infusion to reduce brain swelling. Repeat labs were drawn after administration of both FFP and 4-FPCC and are shown in Table 1. The neurosurgeon decided surgery would occur approximately 48 hours after the last known dose of apixaban.

A repeat head CT at 0500 the next day, approximately 9 hours after FFP administration and 7 hours after 4-FPCC administration, was stable overall with a possible slight increase in size of the parfalcine subdural hematoma. The patient continued to have no neurological symptoms at that time.

On hospital day 3, the patient was taken to the operating room for a 2 left burr hole washout of the subdural hematoma at 0835, approximately 48 hours after the last reported dose of apixaban. Notably, the patient’s PT was prolonged at 14.8 seconds after normalizing the previous day. After surgery, patient became aphasic, disorientated, and encephalopathic. On hospital day 4, the patient became more lethargic and required intubation for respiratory support. Notably, the PT was more prolonged at 16 seconds this day. The patient remained intubated for 4 days and was successfully extubated and placed on nasal canula on day 9.

On day 20, the patient was discharged to a skilled nursing facility for further physical and occupation therapy. The patient’s remaining complication was residual dysphasgia. No anticoagulation was resumed upon discharge.

DISCUSSION

Factor Xa Inhibitor Dosing

Apixaban and rivaroxaban exert their antithrombotic activities through inhibition of fXa, which is part of the intrinsic and extrinsic clotting cascade. This inhibition leads to a decrease in fibrin clot formation and decreased platelet activation and aggregation. FXa inhibitors have a predictable pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic dose response and require dose adjustments based on specific patient characteristics.Apixaban requires a dose reduction to 2.5 mg twice daily if a patient meets 2 of the 3 following criteria: age 80 years old or older, body weight less than or equal to 60 kg, or a serum creatinine greater than or equal to 1.5. Rivaroxaban dose adjustments are indication specific. It is not recommended for use in the treatment of DVT/PE in patients with a CrCl less than 30 mL/min. In nonvalvular AF, the recommended dose adjustment in patients with an estimated CrCl of 15 to 50 mL/min is 15 mg once daily; its use should be avoided in patients with a CrCl less than 15 mL/min.2,3

One of the advantages of the fXa inhibitors is the minimal drug interaction in comparison to warfarin. However, both apixaban and rivaroxaban carry the warning of drug interactions with CYP3A4 strong inducers and p-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitors. Specifically, rivaroxaban was found to have an increased area under the curve (AUC) in patients receiving a P-gp inhibitor with mild renal dysfunction (CrCl 2 Another noteworthy drug interaction occurs with the addition of aspirin to fXa inhibitors. This drug combination has been shown in clinical trials to be associated with an increased risk of bleeding.4,7,8

Of the patients presented in this case series, cases 1 and 2 had 2 interacting medications, amiodarone and aspirin. These drug-drug interactions may have placed these 2 patients at a higher risk of bleeding while on rivaroxaban. Additionally, patient 1 was experiencing acute kidney injury and had a CrCl less than 50 mL/min, which would necessitate a dose adjustment from 20 mg daily to 15 mg daily.

Monitoring of Biological Activity

Routine monitoring of plasma levels is not currently indicated for the oral fXa inhibitors due to the predictive dose response and minimal drug and food interactions. For this reason, specific assays were not originally developed to detect therapeutic plasma levels of these medications. However, when patients present with a hemorrhage or suspected toxic ingestion, laboratory monitoring may be helpful in detecting the presence of these medications. Due to the short half life of the fXa inhibitors (7-11 hours for rivaroxaban and 8-14 hours for apixaban), the timing of the last dose is important. The effect on the coagulation assay will likely be minimal when the drug is at its trough state, which is approximately 12 to 24 hours after the last dose.9,10

The monitoring of the PT is the most widely used coagulation assay in correlating rivaroxaban plasma levels. The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) shows a dose-dependent prolongation of clotting times but is limited, as the correlation is lost in the presence of higher rivaroxaban concentrations. Apixaban is best detected by using a modified PT, which is performed by diluting the reagent. Recently, the development of a specific anti-Xa (aXa) chromogenic assay has been appropriately calibrated for the monitoring of rivaroxaban and apixaban. Unfortunately, this test is not currently available in many clinical practices.9,11

Factor Xa Inhibitor Reversal

Although apixaban and rivaroxaban demonstrated lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage in comparison to warfarin, this adverse event still occurs and has potentially fatal outcomes.4,5 Specific reversal agents and guideline recommendations exist for warfarin reversal, but a major disadvantage when using the fXa inhibitors implicated in this case series is the absence of an available antidote when urgent or emergent reversal is necessary.1

Appropriate initial management of the intracranial hemorrhage includes general supportive measures such as discontinuation of the offending agent, fluid resuscitation, red blood cell transfusion, and early referral for mechanical or surgical intervention. Another consideration may be the administration of activated charcoal, as this was found to lower the concentration of apixaban when given within 6 hours post dose in healthy volunteers.12 However, none of these supportive therapies target the underlying mechanism of action for fXa inhibitors.

fXa inhibitors act to reversibly and competitively block activated factor X, therefore supportive care with FFP can be used to provide hemodynamic support in the event of a massive hemorrhage but will be unlikely to reverse the medication’s anticoagulant effect. No clinical data currently exist that evaluate the effect of FFP on the anticoagulant activity of rivaroxaban or apixaban.

PCCs, activated or inactivated, theoretically could reverse the anticoagulant effects of fXa inhibitors; they contain high concentrations of factors II, IX, and X, as well as factor VII in 4-FPCC and activated PCC (aPCC) and thus can promote thrombin formation.13 Recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) may also be able to reverse the effects of fXa inhibitors. Data are limited on the use of these factor concentrates to reverse major or life-threatening bleeding associated with fXa inhibitors, particularly in humans. A follow-up analysis of major bleeding events in the ROCKET AF trial showed limited use of FFP and use of PCC in only 4 bleeding episodes associated with rivaroxaban anticoagulation.14

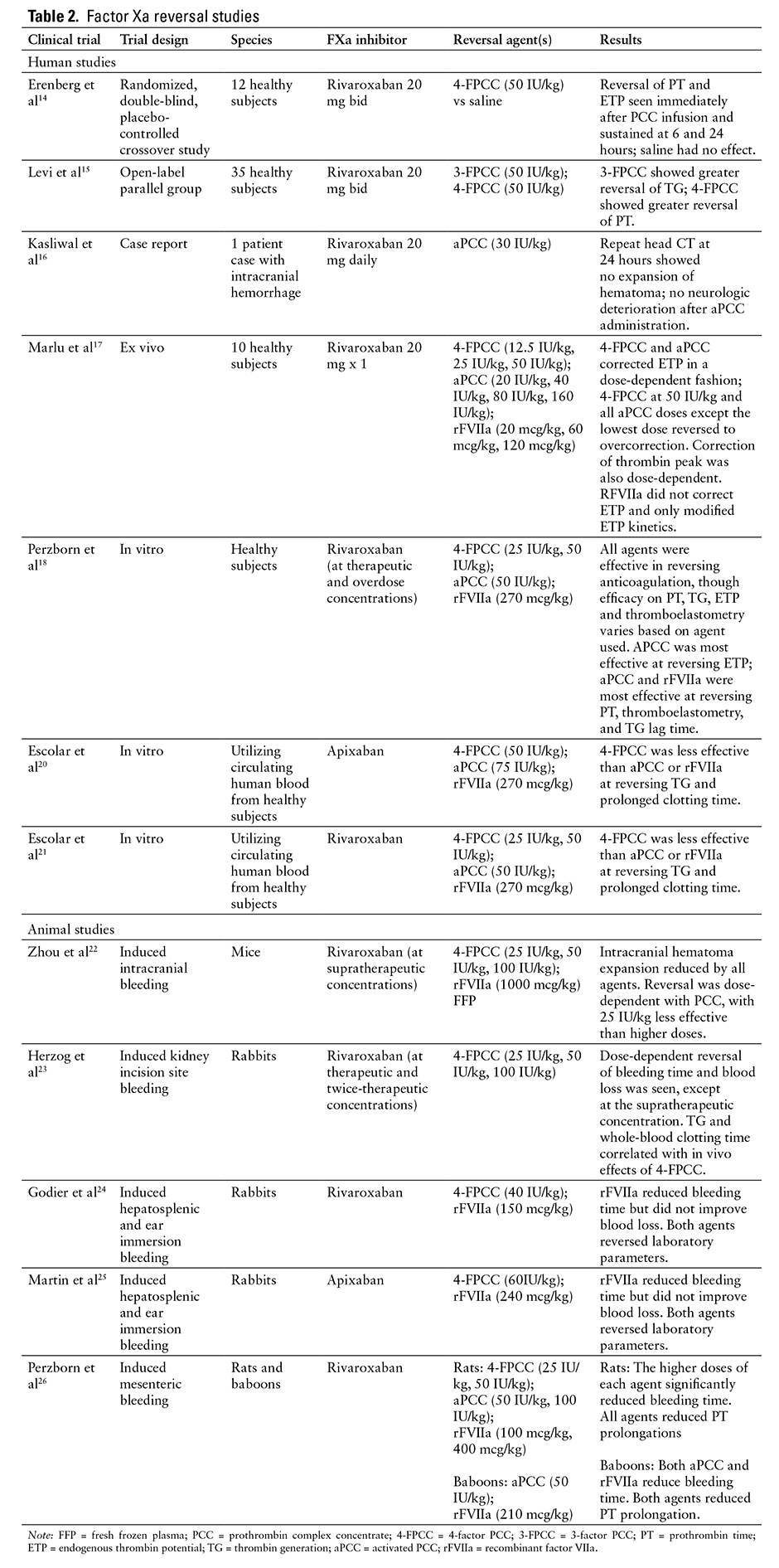

Further data in human subjects are confined to evaluations of the efficacy of PCCs to reverse rivaroxaban-induced anticoagulation. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of 12 healthy male volunteers evaluated the efficacy of 4-FPCC in the reversal of anticoagulation with rivaroxaban, as indicated by PT and endogenous thrombin potential (ETP).15 PCC at a dose of 50 IU/kg completely reversed the anticoagulant effect of rivaroxaban, which occurred immediately after PCC infusion and was sustained at 6 and 24 hours. An open-label, single-center, parallel group study compared the efficacy of 3-factor PCC (3-FPCC) compared to 4-FPCC (50 IU/kg) or saline in reversal of rivaroxaban-induced elevations in PT and thrombin generation (TG) in 35 healthy volunteers.16 4-FPCC reduced PT to a greater extent than 3-FPCC (2.5-3.5 seconds vs 0.6-1 second), whereas 3-FPCC was more effective at reversing alterations in TG than 4-FPCC.

Kasliwal et al recently published a case report of an elderly patient who developed an intracranial hemorrhage while on rivaroxaban for AF, with the last dose of the anticoagulant taken 12 hours prior to onset of neurologic symptoms.17 The patient was treated with aPCC (FEIBA [factor eight inhibitor bypassing activity]) 30 IU/kg, with repeat head CT at 24 hours showing no expansion of hematoma and no worsening of neurologic status. No neurosurgical intervention was performed. Final disposition was discharge to home.

Additional data on the use of PCCs, as well as rFVIIa, exist in ex vivo human studies and in animal models; most of these studies target reversal of anticoagulation parameters such as PT, TG, and ETP as primary endpoints.18-26 These studies have used a variety of doses of PCC, aPCC, and rFVIIa, often at doses much higher than would be typically used in clinical practice. An ex vivo study found a dose-dependent reversal of ETP with PCC and aPCC, with higher doses reversing to overcorrection.18 The changes seen with PCC and aPCC were greater than when using rFVIIa. Another in vitro study found PCC, aPCC, and rFVIIa were all effective in reversing rivaroxaban-induced anticoagulation, but it found that the efficacy of each agent varied based on the anticoagulation parameter assessed.19 An in vitro study of reversal of apixaban anticoagulation utilizing circulating human blood found PCC to be less effective than aPCC or rFVIIa in reversing TG and prolonged clotting time, although doses of aPCC and rFVIIa were higher than used in clinical practice.20 A major limitation of applying in vitro studies is that the extravascular redistribution of the medications is not represented. When the intravascular drug is removed or antagonized, the extravascular drug may redistribute. Therefore, the administration of an antidote would need to account for the amount of drug present in the extravascular tissue.27

Only animal studies have analyzed the effect of factor concentrates on bleeding outcomes. A study of PCC, FFP, and rFVIIa in mice with supratherapeutic rivaroxaban levels found that all agents significantly reduced hematoma expansion, although very high doses of PCC and rFVIIa were utilized.22 The magnitude of effect of PCC on hematoma expansion and neurologic improvement was dose-dependent.

With the overall heterogeneity of existing data and a particular lack of human data, notably data in bleeding humans, the best approach for emergent reversal of anticoagulation due to fXa inhibitors remains unclear. PCC, aPCC, and rFVIIa have each demonstrated some efficacy, although at a wide range of doses. Published data on the efficacy of these reversal agents at various doses are outlined in Table 2. The risk of using these factor concentrates should not be overlooked, as each (particularly rFVIIa) has been associated with thromboembolic events in a dose-dependent fashion.28,29 The specific thromboembolic risk associated with each factor product in a patient population requiring anticoagulation at baseline remains undefined.

A novel reversal agent for fXa inhibitors, andexanet alfa, is currently in phase 3 studies and appears to be a promising option for emergent reversal of fXa inhibitor activity.6 This recombinant protein is structurally similar to native fXa and binds to fXa inhibitors in the blood, preventing inhibition of native Xa activity. Recently announced findings from the first phase 3 trial in 33 subjects receiving apixaban indicate rapid normalization of fXa and thrombin levels with a bolus dose of andexanet alfa; this effect lasted for 1 to 2 hours without administration of a maintenance infusion. Studies with a maintenance infusion and in patients on rivaroxaban are underway.6

Case Review

Due to the lack of a consistent approach used in each patient case, it is difficult to determine a relationship between FFP and PCC administration and efficacious reversal of the oral fXa inhibitors. However, each patient had an initial and follow-up CT to determine whether these agents may have been helpful in stabilizing or reversing the effect of the fXa inhibitors. In addition, labs are presented in Table 1 to show the effect of FFP and/or PCC on the measured coagulation parameters.

When reviewing the 3 patient cases outlined in this article, it appears that reversal and stabilization of the bleed occurred in 2 patients (cases 1 and 3), although this occurred when minimal amounts of the drug would be assumed to be present due to the timing of the last dose and minimal coagulation abnormalities observed upon initial presentation. For this reason, it is difficult to determine whether the addition of the FFP and/or 4-FPCC contributed to the patients’ favorable outcome. The patient in case 1 had no prolongation of the coagulation parameters at presentation and no labs were repeated. The patient in case 3 had only a slightly prolonged PT, which arguably is not sensitive to apixaban that normalized after administration of FFP and 4-FPCC. However, repeat PTs in this patient were slightly prolonged on day 3 and 4 of hospital stay without administration of an anticoagulant. Neither patient had significant progression of the intracranial hemorrhage on repeat CT. The administration of these reversal agents may have contributed to this if in fact some fXa inhibitor activity was still present. In contrast, the patient in case 2 experienced a poor outcome and was the sole patient who had coagulation abnormalities present upon admission. The administration of 4-FPCC alone did not stop progression of the bleed as evident on the repeat CT scan nor did it fully reverse the coagulation abnormalities. Whether this was due to the severity of the bleed or the efficacy, or lack thereof, of 4-PCC itself cannot clearly be determined.

Conclusion

No guidelines currently exist for the reversal of fXa inhibitors, and a review of existing literature provides limited insight on how to manage these patients when they present with an intracranial bleed. The studies currently available were conducted in animal models or healthy human volunteers, which has significant limitations when these data are extrapolated to management of life-threatening hemorrhages.

The cases described indicate that the administration of FFP and 4-FPCC may provide minimal benefit in reversing the coagulation abnormalities caused by fXa inhibitors. However, in patients presenting with a life-threatening intracranial hemorrhage, the administration of these products should still be considered to prevent further progression of the bleed, as this may be more detrimental to the patient than a prothrombotic state caused by these reversal agents. Further data are needed to establish a relationship between FFP and PCC utilization and the reversal of intracranial bleeding due to fXa inhibitors.

REFERENCES

- Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, et al. American College of Chest Physicians: Oral anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e44S-e88S.

- Xarelto (rivaroxaban) [prescribing information]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc; December 2011. Revised January 2015.

- Eliquis (apixaban) [prescribing information]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer Inc; December 2012. Revised August 2014.

- Hyek EM, Held C, Alexander JH, et al. Major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving apixaban or warfarin: The ARISTOTLE trial (Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation): Predictors, characteristics, and clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63(20):2141-2147.

- Patel MR, Mahaffey K, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883-891.

- Crowther M. ANNEXA-A: A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial demonstrating reversal of apixaban-induced anticoagulation in older subjects by andexanet alfa (PRT064445), a universal antidote for factor Xa (fXa) inhibitors. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. November 17, 2014.

- Oldgren J, Wallentin L, Alexander JH et al. New oral anticoagulants in addition to single or dual antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary syndrome a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(22):1670-1680.

- Goodman SG, Wojdyla DM, Piccini JP, et al. Factors associated with major bleeding events: Insights from the ROCKET AF trial (rivaroxaban once-daily oral direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(9):891-900.

- Daelen SV, Peetermans M, Vanassche T et al. Monitoring and reversal strategies for new oral anticoagulants. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;13(1):95-103.

- Wietz JI. Expanding the use of new oral anticoagulants. F1000 Prime Rep. 2014;6:93.

- Miyares MA, Davis K. Newer oral anticoagulants: A review of laboratory monitoring options and reversal agents in the hemorrhagic patient. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(22):1473-1484.

- Wang X, Mondal S, Wang J, et al. Effect of activated charcoal on apixaban pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2014;14:147-154

- Dager WE. Using prothrombin complex concentrates to rapidly reverse oral anticoagulant effects. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:1016-1020.

- Piccini JP, Garg J, Patel MR, et al. Management of major bleeding events in patients treated with rivaroxaban vs. warfarin: Results from the ROCKET AF trial. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1873-1880.

- Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen, PW, Sijpkens MK, et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate. Circulation. 2011;124:1573-1579.

- Levi M, Moore KT, Castillejos CF, et al. Comparison of three-factor and four-factor prothrombin complex concentrates regarding reversal of anticoagulant effects of rivaroxaban in healthy volunteers. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1428-1436.

- Kasliwal MK, Panos NG, Munoz LF et al. Outcome following intracranial hemorrhage associated with novel oral anticoagulants [published online ahead of print July 25, 2014]. J Clin Neurosci.

- Marlu R, Hodah E, Paris A et al. Effect of non-specific reversal agents on anticoagulant activity of dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:217-224.

- Perzborn E, Heitmeier S, Laux V, Buchmuller A. Reversal of rivaroxaban-induced anticoagulation with prothrombin complex concentrate, activated prothrombin complex concentrate, and recombinant activated factor VII in vitro. Thrombosis Res. 2014;133:671-681.

- Escolar G, Fernandez-Gallego V, Arellano-Rodrigo E, et al. Reversal of apixaban induced alterations in hemostasis by different coagulation factor concentrates: Significance of studies in vitro with circulating human blood. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78696.

- Escolar G, Arellano-Rodrigo E, Lopez-Vilchez I, et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban-induced alterations on hemostasis by different coagulation factor concentrates [published online ahead of print December 8, 2014]. Circ J.

- Zhou W, Zorn M, Nawroth P et al. Hemostatic therapy in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage associated with rivaroxaban. Stroke. 2013;44(3):771-778.

- Herzog E, Kaspereit F, Krege W et al. Correlation of coagulation markers and 4F-PCC-mediated reversal of rivaroxaban in a rabbit model of acute bleeding [published online ahead of print January 9, 2015]. Thromb Res.

- Godier A, Midot A, Le Bonniec B et al. Evaluation of prothrombin complex concentrate and recombinant factor VII to reverse rivaroxaban in a rabbit model. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1-9.

- Martin AC, Le Bonniec B, Fischer AM et al. Evaluation of recombinant activated factor VII, prothrombin complex concentrate, and fibrinogen concentrate to reverse apixaban in a rabbit model of bleeding and thrombosis. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168(4):4228-4233.

- Perzborn E, Gruber A, Tinel H et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban anticoagulation by haemostatic agents in rates and primates. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:162-172.

- Greinacher A, Thiele T, Selleng K. Reversal of anticoagulants: An overview of current developments. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:931-942.

- Mayer SA, Brun NC, Begtrup K, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2009;358:2127-2137.

- Bershad EM, Suarez JI. Prothrombin complex concentrates for oral anticoagulant therapy-related intracranial hemorrhage: A review of the literature. Neurocrit Care. 2010;29:171-181.

*PGY2 Critical Care Pharmacy Resident, Avera McKennan Hospital and University Health Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota; †Critical Care Clinical Specialist, PGY2 Critical Care Pharmacy Residency Program Director, Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, South Dakota State University College of Pharmacy, Brookings, South Dakota; ‡PGY1 Pharmacy Resident, Avera McKennan Hospital and University Health Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Corresponding author: Betsy Karli, PharmD, PGY2 Critical Care Pharmacy Resident, Department of Pharmacy, Avera McKennan Hospital and University Health Center, 1325 S. Cliff Avenue, Sioux Falls, SD 57117; phone: 605-322-8357; e-mail: betsy.karli@gmail.com