The Mystery of High-density Lipoprotein: Quantity or Quality? Update on Therapeutic Strategies

Vasiliki Katsi, MD, PhD,1 Manolis S. Kallistratos, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Antonios N. Pavlidis, MD, PhD, FACC,3 Nikos Karpettas, MD, PhD,4 Ioannis Skoumas, MD,5 Nikonas Pavleros, MD,1 Athanasios J. Manolis, MD, FESC, FACC, FAHA,2 Christos Pitsavos, MD, PhD, FESC, FACE,5 Dimitris Tousoulis, MD, PhD, FACC, FESC,5 Christodoulos Stefanadis, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC,5 Ioannis Kallikazaros, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC1

1Department of Cardiology, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece; 2Department of Cardiology, Asklepeion General Hospital, Athens, Greece; 3Department of Cardiology, London Chest Hospital, London, United Kingdom; 4Hypertension Center, Third University Department of Medicine, Athens Medical School, Sotiria Hospital, Athens, Greece; 5First Cardiology Department, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece

This review summarizes the data challenging the concept that cardiovascular protection through high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is only associated with its serum concentration. This conventional impression about its protective role now appears obsolete. New aspects of its mechanisms are revealed and novel therapeutic strategies are based on them. However, data from long-term cost-effectiveness studies of treating HDL are still needed. There is a need for biomarkers that represent the functional characteristics of HDL in order to better quantify the total cardiovascular risk.

[Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16(1):9-19 doi: 1O.3909/ricm0719]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

The Mystery of High-density Lipoprotein: Quantity or Quality? Update on Therapeutic Strategies

Vasiliki Katsi, MD, PhD,1 Manolis S. Kallistratos, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Antonios N. Pavlidis, MD, PhD, FACC,3 Nikos Karpettas, MD, PhD,4 Ioannis Skoumas, MD,5 Nikonas Pavleros, MD,1 Athanasios J. Manolis, MD, FESC, FACC, FAHA,2 Christos Pitsavos, MD, PhD, FESC, FACE,5 Dimitris Tousoulis, MD, PhD, FACC, FESC,5 Christodoulos Stefanadis, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC,5 Ioannis Kallikazaros, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC1

1Department of Cardiology, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece; 2Department of Cardiology, Asklepeion General Hospital, Athens, Greece; 3Department of Cardiology, London Chest Hospital, London, United Kingdom; 4Hypertension Center, Third University Department of Medicine, Athens Medical School, Sotiria Hospital, Athens, Greece; 5First Cardiology Department, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece

This review summarizes the data challenging the concept that cardiovascular protection through high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is only associated with its serum concentration. This conventional impression about its protective role now appears obsolete. New aspects of its mechanisms are revealed and novel therapeutic strategies are based on them. However, data from long-term cost-effectiveness studies of treating HDL are still needed. There is a need for biomarkers that represent the functional characteristics of HDL in order to better quantify the total cardiovascular risk.

[Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16(1):9-19 doi: 1O.3909/ricm0719]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

The Mystery of High-density Lipoprotein: Quantity or Quality? Update on Therapeutic Strategies

Vasiliki Katsi, MD, PhD,1 Manolis S. Kallistratos, MD, PhD, FESC,2 Antonios N. Pavlidis, MD, PhD, FACC,3 Nikos Karpettas, MD, PhD,4 Ioannis Skoumas, MD,5 Nikonas Pavleros, MD,1 Athanasios J. Manolis, MD, FESC, FACC, FAHA,2 Christos Pitsavos, MD, PhD, FESC, FACE,5 Dimitris Tousoulis, MD, PhD, FACC, FESC,5 Christodoulos Stefanadis, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC,5 Ioannis Kallikazaros, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC1

1Department of Cardiology, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece; 2Department of Cardiology, Asklepeion General Hospital, Athens, Greece; 3Department of Cardiology, London Chest Hospital, London, United Kingdom; 4Hypertension Center, Third University Department of Medicine, Athens Medical School, Sotiria Hospital, Athens, Greece; 5First Cardiology Department, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece

This review summarizes the data challenging the concept that cardiovascular protection through high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is only associated with its serum concentration. This conventional impression about its protective role now appears obsolete. New aspects of its mechanisms are revealed and novel therapeutic strategies are based on them. However, data from long-term cost-effectiveness studies of treating HDL are still needed. There is a need for biomarkers that represent the functional characteristics of HDL in order to better quantify the total cardiovascular risk.

[Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16(1):9-19 doi: 1O.3909/ricm0719]

© 2015 MedReviews®, LLC

KEY WORDS

Apolipoprotein A-l • Cardiovascular protection • Dyslipidemia • High-density lipoprotein • Risk factors

KEY WORDS

Apolipoprotein A-l • Cardiovascular protection • Dyslipidemia • High-density lipoprotein • Risk factors

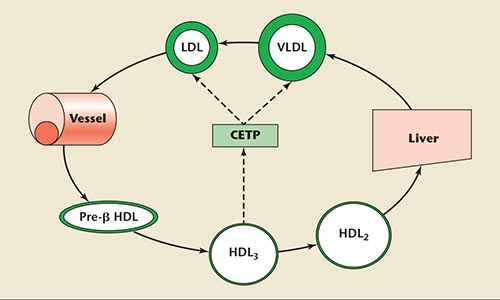

Figure 1. The role of cholesteryl ester transfer protein on cholesterol transport. CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein, HDL, high-density lipoprotein, LDL, low-density lipoprotein, VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

Because cholesterol ester is transferred from HDL to Apo B-containing lipoproteins according to the concentration gradient, CETP seems an attractive possible therapeutic target for raising HDL cholesterol levels.

An increase in HDL levels by 1 mg/dL is associated with 2% to 3% reduction of CV risk.

… some genetically determined low HDL states due to Apo A-I mutations are not always associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis.

HDL and Apo A-I have direct antiatherogenic and vascular protective effects.

… in human studies scavenger receptor B1 inhibitors have shown to temporarily increase HDL levels.

Main Points

• High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels have been proven to be a strong predictor of cardiovascular events, both in patients already on statin treatment, as well as in the general population. Moreover, low HDL cholesterol is the predominant lipid abnormality in a considerable percentage of patients with cardiovascular disease.

• Apolipoprotein A-I (Apo A-I), the major structural protein component of HDL, plays a key role in HDL-derived atheroprotection. The concentration of Apo A-I is the largest predictor of the ability of serum to extract cholesterol from cells.

• The general rule that high HDL levels appear to be beneficial has several exceptions. HDL levels do not always reflect its activity or a uniform distribution of each of its subclasses, especially during treatment. In addition, some genetically determined low HDL states due to Apo A-I mutations are not always associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis.

• Cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) plays a key role in HDL metabolism and has therefore been considered an ideal therapeutic target. CETP inhibitors have demonstrated an ability to increase HDL and decrease lowdensity lipoprotein levels.

Main Points

• Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is usually a complication secondary to migration of a deep venous clot or thrombi to the lungs; other significant etiologies include air, amniotic fluid, fat, and bone marrow. Massive PE is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality due to right ventricular failure, hypoxia, and cardiogenic shock, but little progress has been made in finding an effective pharmacologic intervention for this serious complication.

• Inhaled NO (iNO) has been reported to improve oxygenation and hemodynamics in conjunction with either chemical and/or mechanical thrombolysis in massive PE.

• iNO has multiple effects that suggest a potential therapeutic role in the treatment of acute PE. In addition, in both human and animal studies, NO has been shown to inhibit platelet adhesion and aggregation, prolong bleeding times, and reduce fibrinogen binding; these factors may prevent additional clot formation in acute PE.

• Large, randomized controlled trials need to be performed to determine if iNO provides a mortality benefit in acute PE. Whether NO should be administered to all patients with evidence of RV strain or limited to those with hemodynamic instability also requires further clarification.

Atherosclerosis is a complex process involving numerous interlacing pathways. Lipoprotein vessel wall entry and long-term inflammatory and immune responses play a key role in the atherosclerotic process.1,2 Dyslipidemia is characterized by raised levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), lipoprotein (a), and/ or reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels. Although statin drugs have been proven extremely effective in reducing the total cardiovascular (CV) risk, a residual risk remains in the active treatment arms of most trials.3,4 This residual risk could partially be explained by the coexistence of low levels of HDL cholesterol in patients treated with statins. HDL cholesterol levels have been proven to be a strong predictor of CV events, not only in patients already on statin treatment, but in the general population as well.5-7 Moreover, low HDL cholesterol is the predominant lipid abnormality in a considerable percentage of patients with CV disease.

The correlation between low levels of HDL cholesterol and coronary artery disease (CAD) has been recognized since the 1950s.8 During the 1970s, analysis of data from the Framingham Heart Study showed an independent inverse relationship between HDL levels and the incidence of CAD in both men and women.5 Since then, large epidemiologic studies have confirmed various aspects of the association of HDL levels and CV disease. The Coronary Primary Prevention Trial (CPPT), the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT), and the Lipid Research Clinics (LRC) Follow-up Study showed reduced CV morbidity and mortality in patients with higher serum levels of HDL cholesterol.9 Attenuated progression of CAD by increasing HDL cholesterol has also previously been demonstrated.10

Production, Pathophysiology, and Metabolism of HDL

HDL particles emerge when apolipoprotein A-I (Apo A-I) is synthesized and secreted into the plasma. These premature HDL units convert free cholesterol to cholesteryl esters and deliver it to the liver and the steroidogenic organs. HDL particles follow two pathways to excretion via reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). In the direct pathway, the liver cells collect cholesteryl esters within the HDL molecule through the scavenger receptor class B member 1 and excrete them into the bile.11 In the indirect pathway, these cholesteryl esters are exchanged with triglycerides within LDL and VLDL with the action of cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP). These LDL and VLDL particles, transformed to be rich in cholesterol esters, are collected by the liver cells through the LDL receptor and excrete into the bile.12

CETP is a key participant in the metabolism of HDL—namely, in the transportation from the periphery to the liver (Figure 1). It is a plasma glycoprotein synthesized in the liver, spleen, adipose tissue, and macrophages, and circulates in plasma mainly bound to HDL particles, primarily HDL3 subclasses. It transfers cholesteryl ester and triglycerides between different types of circulating lipoproteins, such as HDL and apolipoprotein B (Apo B)-containing lipoproteins (LDL and VLDL), as well as between HDL subparticles (HDL3, HDL2, and pre-β HDL).13,14 The overall effect of CETP is, therefore, atherogenic. Because cholesterol ester is transferred from HDL to Apo B-containing lipoproteins according to the concentration gradient, CETP seems an attractive possible therapeutic target for raising HDL cholesterol levels.15,16 It has actually been shown that inhibition of CETP is associated with an increase in HDL cholesterol levels.17,18

Apo A-I, the major structural protein component of HDL, plays a key role in HDL-derived atheroprotection. The concentration of Apo A-I is the largest predictor of the ability of serum to extract cholesterol from cells.19 The Apo A-I(Milano) (Apo A-IM) dimer differs because cysteine is substituted at position 173 for arginine, allowing disulfide-linked dimer formation. Data demonstrate that Apo A-IM is most likely the protective component, characterized by a very slow turnover and high efficiency in promoting cell cholesterol efflux.20,21

Another important participant in HDL metabolism is the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1). ABCA1 mediates normal lipidation of the lipid-poor Apo A-I. Tangier disease is a rare genetic disorder caused by nonfunctional ABCA1 and rapid catabolism of Apo A-I.22 As a result, cholesterol accumulates in peripheral tissues, whereas serum levels of HDL cholesterol are very low or undetectable and mostly confined to pre-β HDL.23

The classic concept of RCT was altered with the discovery that the liver and intestine are mainly responsible for lipidation of Apo A-I via the ABCA1. Evaluation of total body cholesterol efflux and RCT would not reflect the atherosclerotic risk because not all cholesterol efflux from tissues is part of the classic RCT model. It is actually the cholesterol efflux from cells that transform into foam cells that seems to be directly related to atherosclerosis. These foam cells are mainly macrophages that take up modified lipoproteins and extracellular debris, including aggregated lipoproteins and dead cells that contain cholesterol.24 Although they probably collect and handle more cholesterol per cell than almost any other cell type (except cells in the liver and intestine), their contribution to the overall efflux of cholesterol from peripheral tissues is minimal.

HDL as an Independent CV Risk Factor

Low HDL cholesterol levels are often associated with diabetes, higher body mass index (BMI), and higher triglyceride and total cholesterol levels. An increase in HDL levels by 1 mg/dL is associated with 2% to 3% reduction of CV risk.25 An inverse relationship between HDL levels and CAD or restenosis following coronary or carotid stenting has been demonstrated.26-28 Data from the Framingham Heart study show that the risk of myocardial infarction (MI) increases by approximately 25% for every 5-mg/dL decrease in HDL levels. The prevalence of low HDL levels in the general population is estimated to be 35% for men and 15% for women, whereas the prevalence in patients with diagnosed CAD has been estimated to be as high as 63%.29 Low HDL levels in these patients are an independent predictor of coronary events.30 The protective role of HDL remains reproducible even in the group of elderly patients.31-34

It is has been noted that, in certain populations, the particle concentrations of LDL (LDL-p) correlate better to the total atherogenic risk, compared with LDL molecule (LDL-c) concentrations. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a study of 5598 subjects without baseline CHD, compared the association of HDL molecule (HDL-c) and HDL-particle (HDL-p) concentrations with carotid intima-media thickness and CAD. The inverse correlation between HDL levels and CAD or carotid atherosclerosis remained significant after adjustment for LDL-p or HDL-p concentrations, but not when adjusted for both. However, the correlation of HDL-p concentrations to CAD and carotid intima-media thickness was significant even after adjustment for LDL-p, HDL-c, or both.34 Moreover, the Apo B:Apo A-I ratio has been shown to have a higher predictive value for future MI compared with the established LDL:HDL ratio.35

Observational analysis of short-and long-term follow-up of individuals with low HDL cholesterol levels who underwent drug-eluting stent implantation after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) shows that these patients are at increased risk of death and adverse cardiac events.36 Similarly, the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) trial suggested that, despite aggressive lipid-lowering treatment with statins after an ACS, HDL cholesterol levels are a better predictor of short-term outcomes. A reduction in the incidence of CV events by 1.4% for every 1 mg/dL increase of HDL cholesterol was noted.37

In contrast, results from the Justification for the Use of statins in Primary prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) trial suggest that, although HDL cholesterol concentrations are indicative of the initial CV risk assessment, these are not predictive of the residual CV risk among patients effectively treated with statin therapy who attain very low levels of LDL cholesterol.38 Likewise, a post hoc analysis of data from the Treating to New Targets (TNT) trial demonstrated that the role of HDL cholesterol is less marked, though still of borderline significance, when the effect of the LDL cholesterol level achieved in patients receiving appropriate hypolipidemic therapy was taken into account.39 However, the relationship remained significant even when the LDL cholesterol levels were less than 70 mg/dL.

The Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial examined the impact of optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention as the initial management strategy in patients with stable CAD and no difference in the primary outcome of death or MI after a mean follow-up of 4.6 years was shown.40 In a post hoc analysis of the COURAGE trial, a significant inverse association between HDL and CV risk was shown and this was independent of other confounders such as age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, BMI, smoking status, and triglyceride levels. Moreover, the predictive role of HDL levels was more pronounced in patients that achieved the optimal target of lipid-lowering therapy (LDL < 70 mg/dL).41

In a substudy of the Second Manifestation of Arterial Disease (SMART) trial, van de Woestijne and colleagues42 showed that low HDL levels were associated with an increased risk of recurrent vascular events in patients with already established vascular disease not receiving lipid-lowering treatment or treated with usual dose lipid-lowering medication. In contrast, in patients on intensive lipid-lowering treatment, low HDL levels were not associated with vascular events.

HDL concentrations are influenced by modifiable factors, such as body weight, exercise, alcohol intake, estrogen levels, smoking, and drugs (eg, diuretics or β-blockers), and nonmodifiable factors such as sex and genetic polymorphisms. Data from family and twin studies indicate that genetic polymorphisms are responsible for 40% to 60% of the interindividual variation of HDL cholesterol levels.43,44 It should be noted that these data could be potentially confounded, as relatives who live together share not only genes but also environment, diet, and lifestyle. However, studies of identical twins being reared apart support more firmly that genetic polymorphism is the major determinant of HDL levels.45,46

The general rule that high HDL levels appear to be beneficial has several exceptions. HDL levels do not always reflect the activity or uniform distribution of each of its subclasses, especially during treatment. In addition, some genetically determined low HDL states due to Apo A-I mutations are not always associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis.47,48 Similarly, elevated HDL levels due to CETP gene mutations, resulting in CETP deficiency, are not uniformly atheroprotective .49,50

In several randomized clinical trials hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been shown to increase the risk of CAD51,52 or offer no protection against CAD.53,54 HRT has been shown to lower plasma LDL and increase HDL, and therefore improve lipid profiles, with the exception of increasing plasma triglyceride levels. Lamon-Fava and colleagues55 compared the effects of HRT on plasma lipoproteins and CAD progression in postmenopausal women with and without diabetes. A significant interaction between HRT and diabetes was observed, with greater increases in plasma atheroprotectivesubfractions: the lipid-rich HDLα1 particles in nondiabetic women than in diabetic women taking HRT, although no differences in quantitative angiography were shown.

HDL can be separated by ultra-centrifugation into two major subfractions: the lipid-rich HDL2 and the lipid-poor HDL3. The relation of each subfraction to CV risk compared with total HDL levels remains controversial. Several studies have shown that the HDL2 subclass is strongly associated with the risk of CAD.56,57 Bakogianni and associates58 demonstrated that, in patients with diabetes, HDL2 and HDL3 subfractions are influenced by the metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. In these subjects with low LPL activity, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins are slowly hydrolyzed, promoting the formation of HDL3 particles, whereas HDL2 cholesterol levels are significantly reduced. HDL2 is the more variable subclass and reflects changes in HDL; it has been suggested that the protective role of total HDL against CAD is mainly mediated through the HDL2 fraction.58

Mechanisms of HDL Protection

Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidative Effects

Numerous studies have investigated the pathways and mechanisms of the atheroprotective role of HDL. Because HDL cholesterol levels do not always reflect this role, many studies have focused on the functional assessment of HDL particles. Inhibition of LDL oxidation and removal of excess cholesterol from the arterial wall via RCT are two crucial components of the atheroprotective process. As a result, HDL decreases the expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, and restrains the binding of mononuclear cells to the vessel wall.59,60

HDL and Apo A-I have direct antiatherogenic and vascular protective effects. Oxidative LDL stimulates proinflammatory genes and triggers inflammatory cell recruitment.61,62 The major anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic effect of HDL is achieved via inhibition of LDL oxidation. These antioxidant effects of HDL have been mostly attributed to its ability to bind with transition metals and the presence of paraoxonase (PON), a powerful antioxidant enzyme carried by HDL particles.63,64 The contribution of PON to the atheroprotective role of HDL has been clearly demonstrated both in animal and human studies.65,66 Apart from PON, several other enzymes related to the HDL molecule have been shown to have antioxidative effects, such as platelet-activating factor (PAF) acetylhydrolase and glutathione peroxidase.67

LDL oxidation produces noxious metabolites, such as lysophosphatidylcholine, which damages the endothelium, and 25-hydroxycho-lesterol, which has apoptotic effects to smooth muscle cells. HDL has been shown to enhance the removal of lysophosphatidylcholine and other oxidative products and facilitate their catabolism in the liver.68-70

HDL and Apo A-I suppress the expression of genes related to inflammatory cytokines and endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecules such as the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, the intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin, and inhibit binding of mononuclear cells, therefore reducing the inflammatory process within the vessel wall. In addition, the release of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor is inhibited by binding of HDL particles to lipopolysaccharide and endotoxins.71,72

Attenuation of Endothelial Dysfunction

Endothelial dysfunction results from the combined effect of atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia, and LDL oxidation. HDL and Apo A-I have been shown to inhibit this process or even reverse the reduced vasodilator capacity resulting from endothelial dysfunction.73,74 Moreover, HDL cholesterol levels have been correlated to endothelium-dependent vasodilator responses of the coronary arteries.75,76

Antithrombotic Effects

Nitric oxide and prostacyclin are two major antiatherogenic and antithrombotic molecules released by vascular cells. HDL appears to be able to stimulate their synthesis and release by stimulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase, as well as preventing oxidized LDL to inhibit its action.77,78

The antithrombotic effects of HDL cholesterol are achieved mainly by inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation, enhancement of the anticoagulant action of proteins C and S, and stimulation of fibrinolysis.79-83 Additional antithrombotic effects are derived through activation of PAF acetylhydrolase.84-86 In addition, it has been shown that HDL reduces the endothelial expression of thrombin-induced tissue factor which activates the extrinsic coagulation pathway.87

Treatment Strategies

As previously described, HDL exerts anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic effects by inhibiting LDL oxidation, acting as a scavenger of oxidized lipids, reducing platelet activity, stimulating fibrinolysis, and improving endothelial function. All of these pathways and intercessors are potential targets for new treatment strategies that could enhance the atheroprotective effects of HDL cholesterol.

Although it is generally accepted that an increase in HDL levels is beneficial, the target levels still vary significantly. Moreover, novel methods of measuring the qualitative characteristics of HDL and the efficiency of RCT mechanisms are necessary. Furthermore, prospective studies assessing the clinical effects of increasing HDL cholesterol levels are limited and long-term cost-effectiveness data are required. There is also lack of sensitive biomarkers that adequately correspond to the protective effects of HDL.

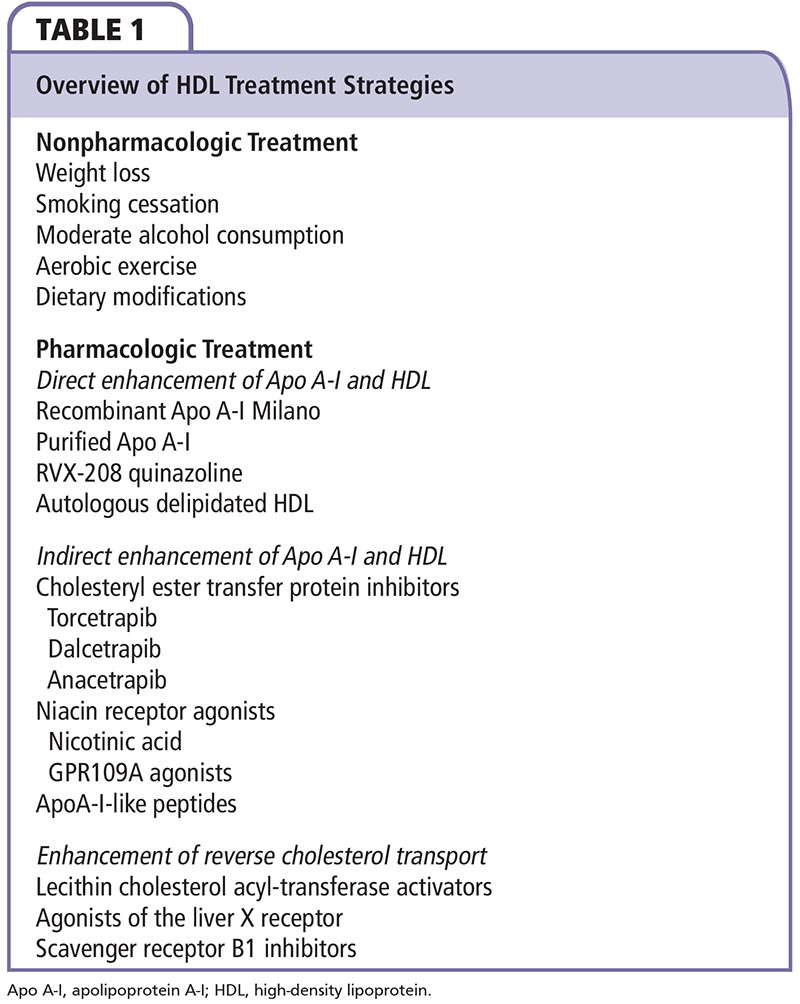

The main goal in treatment of dyslipidemias remains the lowering of LDL levels. Numerous studies have shown that statins reduce the risk for nonfatal MI and CV death.88,89 Nevertheless, regardless of baseline LDL levels, additional strategies to increase HDL cholesterol can further reduce the CV risk in patients already treated with statins. HDL therapeutic strategies are classified into pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic categories and are summarized in Table 1.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

The nonpharmacologic strategies include body weight loss, increase in exercise, smoking cessation, moderate alcohol intake, and altering dietary habits (Table 1). Results from the Framingham Study demonstrate that obese persons have lower HDL levels and a weight increase of approximately 5 pounds or 1 unit of BMI is associated with a 5% decrease in HDL levels.90 Similarly, HDL increases by 0.35 mg/dL/kg of weight loss.91,92

Data from the same study show that HDL levels in smokers are 3 to 5 mg/dL lower compared with nonsmokers.93 Moderate alcohol consumption (30-40 g or 2 units per day) increases HDL levels and decreases the risk of CAD irrespective of the type of alcohol.94-96 It appears reasonable to encourage regular moderate alcohol consumption rather than complete abstinence.

The protective effects of exercise were also shown in the Framingham Study; participants who exercised 1 hour or more per week had higher HDL levels by 6 to 7 mg/dL in men and 7 to 8 mg/dL in women, and 15% to 25% reduced CV risk.97 Optimal increase in HDL levels is achieved by efficient aerobic exercise performed five times per week for approximately 30 minutes.98 A diet low in fat and rich in fiber, in combination with exercise, has been shown to increase the anti-inflammatory effects of HDL.98 Efforts should be made to replace transfatty acids and saturated fatty acids with unsaturated fat. Furthermore, estrogen therapy seems to prevent the decrease in HDL levels associated with menopause in women.99-100 However, the risk-to-benefit balance of post-menopausal estrogens on the CV system, osteoporosis, and malignancy is still debatable.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Strategies Directly Enhancing Apo A-l and HDL.

ApoA-IM is a variant of Apo A-L Although Apo A-IM carriers have very low HDL levels, they demonstrate significantly less atherosclerosis. Animal studies showed that recombinant Apo A-IM mobilizes cholesterol and thereby reduces the atherosclerotic plaque burden.101 Interestingly, these antiatheroscle-rotic effects are observable 48 hours after a single infusion of recombinant Apo A-IM. This strategy was tested in a study of 47 subjects receiving intravenous infusion of recombinant Apo A-IM at weekly intervals.102 The rapidity and magnitude of the changes in atherosclerotic burden seen have not been previously described. A reduction of 4.2% in total atheroma volume, as assessed by coronary intravascular ultrasound, was found only after 5 weeks of treatment. In comparison, a reduction of 0.4% in angiographic stenosis after 3 years of treatment with combination therapy of statin and niacin has previously been described.103

Another approach was the administration of complexes of purified Apo A-I and phosphatidylcholine. Tardif and associates104 randomized 145 patients who presented with an ACS to either four weekly infusions or placebo and demonstrated an atheroma volume reduction of 3.4% in the active treatment arm. Comparatively, similar atheroma reduction with a statin can be achieved after 2 years of treatment.105,106 Although some cases of hypotension were reported in this trial, the effects on blood pressure were not thoroughly assessed. Further studies suggest that purified Apo A-I infusions stimulate the expression of endothelial adhesion molecule, increase HDL cholesterol levels, enhance cholesterol efflux from macrophages, and inhibit platelet aggregation.107-109

The synthetic molecule of the antimalarial quinazoline (RVX-208) has been found to enhance Apo A-I production. In an animal study, it was shown to increase plasma Apo A-I and HDL cholesterol levels up to 60% and 97%, respectively, with no effect on Apo B or LDL cholesterol levels.110 Similarly in humans, oral treatment with RVX-208 resulted in increase of Apo A-I and preβ-HDL levels by 10% and 42% respectively.110

Autologous delipidated HDL is derived by collection of approximately 1 liter of plasma by apheresis, selective lipid removal from HDL particles and reinfusion of the remaining preβ-HDL. Preclinical evaluation has shown a 6.9% reduction in aortic atheroma volume.111

Strategies Indirectly Enhancing ApoA-l and HDL

CETP inhibitors. CETP plays a key role in HDL metabolism and has therefore been considered an ideal therapeutic target. CETP inhibitors, such as torcetrapib, have demonstrated an ability to increase HDL and decrease LDL levels. The Investigation of Lipid Level Management Using Coronary Ultrasound to Assess Reduction of Atherosclerosis by CETP Inhibition and HDL Elevation (ILLUSTRATE) trial showed that combination therapy with torcetrapib and a statin resulted in higher atherosclerotic regression compared with statin monotherapy, although this difference was observed only in the highest quartile of HDL increase. No benefit was observed in the whole cohort and higher rates of hypertension were demonstrated in the group receiving combination therapy.112 Similarly disappointing results were seen in the Investigation of Lipid Level Management to Understand its Impact in Atherosclerotic Events (ILLUMINATE) trial, a large trial of 15,067 patients in which, despite the increase of HDL levels, a higher overall CV mortality was noted in the torcetrapib group. Although no clear pathophysiologic explanation was found, this was mainly attributed to an increase in sodium and aldosterone levels, potassium depletion, and an increase in blood pressure. The hypothesis that large, cholesterol-enriched HDL molecules could act as cholesterol donors instead of acceptors has not been adequately supported.113

Dalcetrapib and anacetrapib are two CETP inhibitors with similar atheroprotective effects to torcetrapib, but no significant adverse effects.114 However, the clinical testing of dalcetrapib (dal-OUTCOMES trial) was recently halted due to lack of significant benefit in patients with recent ACS.115 Anacetrapib is still under evaluation in clinical studies. It appears to be a more potent CETP inhibitor, increasing HDL by more than 100%, as compared with the approximate 30% increase seen with dalcetrapib.

Niacin receptor agonists. Nicotinic acid, a form of niacin, has been used in the treatment of dyslipidemia for several decades and it is the only form of niacin that has been shown to increase HDL and decrease LDL and triglyceride levels. In addition, it reduces the very atherogenic small, dense LDL particles and increases the atheroprotective large HDL particles.116 However, the significant adverse effects of niacin, mainly related to skin reactions, have prevented its widespread use in the treatment of dyslipidemias.

The Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcomes (AIM-HIGH) trial included 3424 patients with established CV disease, low HDL levels, and raised triglycerides, randomized to high-dose versus low-dose niacin. The trial was stopped prematurely after 3-year median follow-up in view of absence of incremental clinical benefit from the addition of niacin to standard hypolipidemic treatment, despite improvement in HDL and triglyceride levels. Moreover, there was a small increase in the incidence of ischemic stroke in the niacin group.117

The Heart Protection Study 2-Treatment of HDL to Reduce the Incidence of Vascular Events (HPS2-THRIVE) trial included 25,673 patients with established CV disease. Subjects were randomized to extended-release niacin and laropiprant (an antiflushing agent) versus placebo. Both groups were pretreated with simvastatin with or without ezetimibe to maintain a total cholesterol target of < 135 mg/ dL. After 4-year follow-up, 13.2% had major vascular events in the treatment group versus 13.7% in the placebo group (P = .29), with significant increases in nonfatal side effects in the treatment group.118

The discovery of the niacin receptor GPR109A led to the development of synthetic agonists of the receptor with the hope that they would carry the benefits of niacin treatment but not its adverse effects. Disappointingly, the incidence of skin reactions (flushing) remained high.119 However, the development of partial niacin receptor agonists remains promising.120

Apo A-1-1 ike peptides. The use of peptides that imitate the functions of Apo A-I by enhancing cholesterol efflux from macrophages and offloading of cholesterol to he-patocytes via the scavenger receptor Bl has shown encouraging results.121-123 Moreover, animal studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties similar to Apo A-I and deceleration of the atheromatic process.124-126

Strategies Enhancing RCT.

Lecithin cholesterol acyl-transferase activators. Lecithin cholesterol acyl-transferase (LCAT) esterifies cholesterol, allowing it to enter and remain in the hydrophobic core of HDL. Reduced activity of the enzyme leads to lower HDL cholesterol levels. Despite its crucial involvement in the metabolism of HDL, its role in RCT and the atherosclerotic process remains controversial.127,128 For example, a cross-sectional analysis of carriers of mutations leading to LCAT deficiency suggested no increase in carotid intima media thickness, despite lower HDL cholesterol levels.129 Impressively, analysis of data from the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease (PREVEND) study revealed that enhanced LCAT activity independently predicted an increased risk of CV events.130 However, further studies of LCAT activators are warranted in view of their ability to raise HDL cholesterol levels and the possible beneficial influence on RCT.

Agonists of the liver X receptor. Liver X receptors (LXRs) are activated by oxidized forms of cholesterol and bind to promoters in order to regulate the transcription of numerous genes, including those involved in lipid homeostasis. The two LXR isoforms (LXRα and LXRβ) differ only in tissue distribution.131 Treatment with endogenous LXR agonists showed to augment the mobilization of cholesterol from macrophages and the transport of foam cells to the liver.132,133 On the other hand, through interaction with other genes, LXR agonists induce the expression of lipogenic genes in the liver, promoting hepatic steatosis.134 Therefore, further investigation is needed before, if ever, they become a useful therapeutic instrument.

Scavenger receptor class B1 inhibitors. Scavenger receptor B1 is a receptor involved in the uptake of cholesterol esters from HDL, VLDL, and native LDL by the liver, as a part of the direct pathway of RCT. Only limited data are available on its potential role as a therapeutic target. The absence of this receptor in mice leads to increased LDL levels and acceleration of the atherosclerotic process; in human studies, scavenger receptor B1 inhibitors have shown to temporarily increase HDL levels.135,136 More data on the potential beneficial effects of this treatment strategy are expected.

Assessment of HDL modification. Several studies have assessed the effects of HDL modification on the atherosclerotic burden. Voros and colleagues137 evaluated the association between lipoproteins and plaque components with the use of coronary computed tomography angiography and intravascular ultrasound and demonstrated that small HDL particles are associated with larger plaque burden and more noncalcified plaque, whereas larger HDL and pre-β32 HDL particles are linked to smaller plaque burden and less noncalcified plaque.137 Several studies have demonstrated that patients with high HDL levels after treatment show significant decrease in carotid intima-media thickness compared with patients with low HDL levels.138,139

Conclusions

The conventional impression about the protective role of HDL based on quantity now appears obsolete. There is a need of risk restratification based on novel biomarkers that represent the activity and functional capacity of HDL. New aspects of physiologic mechanisms are revealed and novel therapeutic strategies are based on them. However, more clinical data are required. ![]()

The authors report no real or apparent conflicts of interest.

References

- Ross R. Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115-126.

- Shah PK. Plaque disruption and thrombosis: potential role of inflammation and infection. Cardiol Clin. 1999;17:271-281.

- Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandispronavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994,344:1383-1389.

- The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349-1357.

- Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, et al. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977:62:707-714.

- Frost PH, Davis BR, Burlando AJ, et al. Serum lipids and incidence of coronary heart disease. Findings from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). Circulation. 1996;94:2381-2388.

- Sacks FM, Tonkin AM, Shepherd J, et al. Effect of pravastatin on coronary disease events in sub groups defined by coronary risk factors: the Prospective Pravastatin Pooling Project. Circulation. 2000:102:1893-1900.

- Nikkilä E. Studies on the lipid-protein relationship in normal and pathological sera and the effect of heparin on serum lipoproteins. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1953;5 Suppl 8:9-100.

- Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, et al. High- density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies. Circulation. 1989;79:8-15.

- Ballantyne CM, Herd JA, Ferlic LL, et al. Influence of low HDL on progression of coronary artery disease and response to fluvastatin therapy. Circulation. 1999:99:736-743.

- Meyers CD, Kashyap ML. Pharmacologic elevation of high-density lipoproteins: recent insights on mechanism of action and atherosclerosis protection. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:366-373.

- Lewis GF, Rader DJ. New insights into the regulation of HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport. Ore Res. 2005;96:1221-1232.

- Tall AR. Plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein. J LipidRes. 1993;34:1255-1274.

- Marcel YL, McPherson R, Hogue M, et al. Distribution and concentration of cholesteryl ester transfer protein in plasma of normolipemic subjects. J Clin Invest. 1990:85:10-17.

- HaYC, Gorjatschko L, Barter PJ. Changes in the density distribution of pig high density lipoproteins during incubation in vitro. Influence of esterified cholesterol transfer activity. Atherosclerosis. 1983;48:253-263.

- Paromov VM, Morton RE. Lipid transfer inhibitor protein defines the participation of high-density lipoprotein subfractions in lipid transfer reactions mediated by cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP). J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40859-40866.

- de Grooth GJ, Kuivenhoven JA, Stalenhoef AF, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor, JTT-705, in humans: a randomized phase II dose-response study. Circulation. 2002;105:2159-2165.

- Kuivenhoven JA, de Grooth GJ, Kawamura H, et al. Effectiveness of inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer protein by JTT-705 in combination with pravastatin in type II dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95: 1085-1088.

- Franceschini G, Calabresi L, Chiesa G, et al. Increased cholesterol efflux potential of sera from ApoA-IMilano carriers and transgenic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1257-1262.

- Roma P, Gregg RE, Meng MS, et al. In vivo metabolism of a mutant form of apolipoprotein A-I, apoA-IMilano, associated with familial hypoalphalipoproteinemia. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1445-1452.

- Calabresi L, Canavesi M, Bernini F, Franceschini G. Cell cholesterol efflux to reconstituted high-density lipoproteins containing the apolipoprotein A-IMilano dimer. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16307-16314.

- Rust S, Rosier M, Funke H, et al. Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1. Nat Genet. 1999;22: 352-355.

- McNeish J, Aiello RJ, Guyot D, et al. High density lipoprotein deficiency and foam cell accumulation in mice with targeted disruption of ATP-binding cassette transporter-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97: 4245-4250.

- Rader DJ, Puré E. Lipoproteins, macrophage function, and atherosclerosis: beyond the foam cell? Cell Metab. 2005;1:223-230.

- Genest J Jr, Marcil M, Denis M, Yu L. High density lipoproteins in health and in disease. J Investig Med. 1999;47:31-42.

- Fager G, Wiklund O, Olofsson SO, et al. Serum apolipoprotein levels in relation to acute myocardial infarction and its risk factors: apolipoprotein A-I levels in male survivors of myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 1980;36:67-74.

- Shah PK, Amin J. Low high density lipoprotein level is associated with increased restenosis rate after coronary angioplasty. Circulation. 1992;85:1279-1285.

- Reis GJ, Kuntz RE, Silverman DI, Pasternak RC. Effects of serum lipid levels on restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:1431-1435.

- Johnson CL, Rifkind BM, Sempos CT, et al. Declining serum total cholesterol levels among US adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination surveys. JAMA. 1993;269:3002-3008.

- Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, et al. Distribution of lipids in 8500 men with coronary artery disease. Department of Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1196-1201.

- Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Jonkers IJ, van Exel E, et al. High-density vs low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as the risk factor for coronary artery disease and stroke in old age. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163: 1549-1554.

- Nikkilä M, Pitkäjärvi T, Koivula T, Heikkinen J. Elevated high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and normal triglycerides as markers of longevity. Klin Wochenschr. 1991;69:780-785.

- Nikkilä M, Heikkinen J. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and longevity. Age Ageing. 1990;19:119-124.

- Mackey RH, Greenland P, Goff DC Jr, et al. Highdensity lipoprotein cholesterol and particle concentrations, carotid atherosclerosis, and coronary events: MESA (multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:508-516.

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al; INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;354:937-952.

- Wolfram RM, Brewer HB, Xue Z, et al. Impact of low high-density lipoproteins on in-hospital events and one-year clinical outcomes in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction acute coronary syndrome treated with drug-eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:711-717.

- Olsson AG, Schwartz GG, Szarek M, et al. High-density lipoprotein, but not low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels influence short-term prognosis after acute coronary syndrome: results from the MIRACL trial. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:890-896.

- Ridker PM, Genest J, Boekholdt SM, et al; JUPITER Trial Study Group. HDL cholesterol and residual risk of first cardiovascular events after treatment with potent statin therapy: an analysis from the JUPITER trial. Lancet. 2010;376:333-339.

- Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, et al; Treating to New Targets Investigators. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1301-1310.

- Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al; COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503-1516.

- Acharjee S, Boden WE, Hartigan PM, et al. Low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increased risk of cardiovascular events in stable ischemic heart disease patients: a post-hoc analysis from the COURAGE Trial (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1826-1833.

- van de Woestijne AP, van der Graaf Y, Liem AH, et al; SMART Study Group. Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is not a risk factor for recurrent vascular events in patients with vascular disease on intensive lipid-lowering medication. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1834-1841.

- Bucher KD, Friedlander Y, Kaplan EB, et al. Biological and cultural sources of familial resemblance in plasma lipids: a comparison between North America and Israel-the Lipid Research Clinics Program. Genet Epidemiol. 1988;5:17-33.

- Perusse L, Despres JP, Tremblay A, et al. Genetic and environmental determinants of serum lipids and lipoproteins in French Canadian families. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:308-318.

- Heller DA, de Faire U, Pedersen NL, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on serum lipid levels in twins. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1150-1156.

- Heller DA, Pedersen NL, de Faire U, McClearn GE. Genetic and environmental correlations among serum lipids and apolipoproteins in elderly twins reared together and apart. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:1255-1267.

- Franceschini G, Sirtori CR, Capurso A 2nd, et al. A-IMilano apoprotein. Decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels with significant lipoprotein modifications and without clinical atherosclerosis in an Italian family. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:892-900.

- Rader DJ, Ikewaki K, Duverger N, et al. Very low highdensity lipoproteins without coronary atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1993;342:1455-1458.

- Inazu A, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H. CETP deficiency. [Article in Japanese] Nippon Rinsho. 1994;52:3216-3220.

- Mabuchi H, Yagi K, Haraki T, et al. Molecular genetics of cholesterol transport and cholesterol reverse transport disorders (familial hypercholesterolemia and CETP deficiency) and coronary heart disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;748:333-341.

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

- Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605-613.

- Herrington DM, Reboussin DM, Brosnihan KB, et al. Effects of estrogen replacement on the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:522-529.

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701-1712.

- Lamon-Fava S, Herrington DM, Horvath KV, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on plasma lipoprotein levels and coronary atherosclerosis progression in postmenopausal women according to type 2 diabetes mellitus status. Metabolism. 2010;59: 1794-1800.

- Salonen JT, Salonen R, Seppanen K, et al. HDL, HDL2, and HDL3 subfractions, and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. A prospective population study in eastern Finnish men. Circulation. 1991;84:129-139.

- Johansson J, Nilsson-Ehle P, Carlson LA, Hamsten A. The association of lipoprotein and hepatic lipase activities with high density lipoprotein subclass levels in men with myocardial infarction at a young age. Atherosclerosis. 1991;86:111-122.

- Bakogianni MC, Kalofoutis CA, Skenderi KI, Kalofoutis AT. Clinical evaluation of plasma high-density lipoprotein subfractions (HDL2, HDL3) in non-insulin-dependent diabetics with coronary artery disease. J Diabetes Complications. 2001;15:265-269.

- Barter PJ, Baker PW, Rye KA. Effect of high-density lipoproteins on the expression of adhesion molecules in endothelial cells. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13: 285-288.

- Marathe GK, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase, and not paraoxonase-1, is the oxidized phospholipid hydrolase of high density lipoprotein particles. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3937-3947.

- Navab M, Berliner JA, Watson AD, et al. The yin and yang of oxidation in the development of the fatty streak: a review based on the 1994 George Lyman Duff Memorial Lecture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:831-842.

- Navab M, Hama SY, Nguyen TB, Fogelman AM. Monocyte adhesion and transmigration in atherosclerosis. Coron Artery Dis. 1994;5:198-204.

- Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Thérond P, Beaudeux JL, et al. High density lipoproteins (HDL) and the oxidative hypothesis of atherosclerosis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:939-948.

- Mackness MI, Arrol S, Abbott CA, Durrington PN. Is paraoxonase related to atherosclerosis? Chem Biol Interact. 1993;87:161-171.

- Hegele RA. Paraoxonase genes and disease. Ann Med. 1999;31:217-224.

- Shih DM, Gu L, Xia YR, et al. Mice lacking serum paraoxonase are susceptible to organophosphate toxicity and atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:284-287.

- Podrez EA. Anti-oxidant properties of high-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:719-725.

- Xia P, Vadas MA, Rye KA, et al. High density lipoproteins (HDL) interrupt the sphingosine kinase signaling pathway: a possible mechanism for protection against atherosclerosis by HDL. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33143-33147.

- Matsuda Y, Hirata K, Inoue N, et al. High density lipoprotein reverses inhibitory effect of oxidized low density lipoprotein on endothelium-dependent arterial relaxation. Circ Res. 1993;72:1103-1109.

- Bowry VW, Stanley KK, Stocker R. High density lipoprotein is the major carrier of lipid hydroperoxides in human blood plasma from fasting donors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10316-10320.

- Nilsson J, Dahlgren B, Ares M, et al. Lipoprotein-like phospholipid particles inhibit the smooth muscle cell cytotoxicity of lysophosphatidylcholine and platelet-activating factor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:13-19.

- Shah PK, Nilsson J, Kaul S, et al. Effects of recombinant apolipoprotein A-I(Milano) on aortic atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 1998;97:780-785.

- Ameli S, Hultgardh-Nilsson A, Cercek B, et al. Recombinant apolipoprotein A-IMilano reduces intimal thickening after balloon injury in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Circulation. 1994;90:1935-1941.

- van der Steeg WA, Holme I, Boekholdt SM, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein particle size, and apolipoprotein A-I: significance for cardiovascular risk: the IDEAL and EPIC-Norfolk studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51: 634-642.

- Vogel RA. Coronary risk factors, endothelial function, and atherosclerosis: a review. Clin Cardiol. 1997;20:426-432.

- Zeiher AM, Schächlinger V, Hohnloser SH, et al. Coronary atherosclerotic wall thickening and vascular reactivity in humans: elevated high-density lipoprotein levels ameliorate abnormal vasoconstriction in early atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1994;89: 2525-2532.

- Zeiher AM. Endothelial modulation of coronary vasomotor tone in humans. Effects of atherosclerosis and risk factors for coronary artery disease. Arzneimittelforschung. 1994;44:439-442.

- Yuhanna IS, Zhu Y, Cox BE, et al. High-density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor-BI activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat Med. 2001;7:853-857.

- Uittenbogaard A, Shaul PW, Yuhanna IS, et al. High density lipoprotein prevents oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced inhibition of endothelial nitricoxide synthase localization and activation in caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11278-11283.

- Naqvi TZ, Shah PK, Ivey PA, et al. Evidence that high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is an independent predictor of acute platelet-dependent thrombus formation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:1011-1017.

- Saku K, Ahmad M, Glas-Greenwalt P, Kashyap ML. Activation of fibrinolysis by apolipoproteins of high density lipoproteins in man. Thromb Res. 1985;39:1-8.

- Berliner JA, Heinecke JW. The role of oxidized lipoproteins in atherogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:707-727.

- Leitinger N, Watson AD, Faull KF, et al. Monocyte binding to endothelial cells induced by oxidized phospholipids present in minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein is inhibited by a platelet activating factor receptor antagonist. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;433: 379-382.

- Griffin JH, Kojima K, Banka CL, et al. High density lipoprotein enhancement of anticoagulant activities of plasma protein S and activated protein C. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:219-227.

- Li D, Weng S, Yang B, et al. Inhibition of arterial thrombus formation by ApoA1 Milano. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:378-383.

- Subbanagounder G, Leitinger N, Shih PT, et al. Evidence that phospholipid oxidation products and/or platelet-activating factor play an important role in early atherogenesis: in vitro and in vivo inhibition by WEB 2086. Circ Res. 1999;85:311-318.

- Viswambharan H, Ming XF, Zhu S, et al. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein inhibits thrombin-induced endothelial tissue factor expression through inhibition of RhoA and stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase but not Akt/endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circ Res. 2004;94:918-925.

- The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. I. Reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1984;251:351-364.

- Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001-1009.

- Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. Longitudinal and secular trends in lipoprotein cholesterol measurements in a general population sample: the Framingham Offspring Study. Arteriosclerosis. 1987;68:59-66.

- Dattilo AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Effects of weight reduction on blood lipids and lipoproteins: a metaanalysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:320-328.

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-2497.

- Wilson PW, Garrison RJ, Abbott RD, Castelli WP. Factors associated with lipoprotein cholesterol levels: the Framingham Study. Arteriosclerosis. 1983;3:273-281.

- Ansell BJ, Fonarow GC, Fogelman AM. High-density lipoprotein: is it always atheroprotective? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2006;8:405-411.

- Valmadrid CT, Klein R, Moss SE, et al. Alcohol intake and the risk of coronary heart disease mortality in persons with older-onset diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1999;282:239-246.

- Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Breslow JL, et al. Moderate alcohol intake, increased levels of high-density lipoprotein and its subfractions, and decreased risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;329: 1829-1834.

- Dannenberg AL, Keller JB, Wilson PW, Castelli WP. Leisure time physical activity in the Framingham Offspring Study: description, seasonal variation, and risk factor correlates. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:76-88.

- Roberts CK, Ng C, Hama S, et al. Effect of a shortterm diet and exercise intervention on inflammatory/ anti-inflammatory properties of HDL in overweight/ obese men with cardiovascular risk factors. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1727-1732.

- Wilson PW, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. Postmenopausal estrogen use, cigarette smoking, and cardiovascular morbidity: the Framingham Study. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1038-1043.

- Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, et al. A prospective study of postmenopausal estrogen therapy and coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;313: 1044-1049.

- Shah PK, Yano J, Reyes O, et al. High-dose recombinant apolipoprotein A-I(Milano) mobilizes tissue cholesterol and rapidly reduces plaque lipid and macrophage content in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:3047-3050.

- Nissen SE, Tsunoda T, Tuzcu EM, et al. Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290: 2292-2300.

- Brown BG, Zhao XQ, Chait A, et al. Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1583-1592.

- Tardif JC, Grégoire J, L’Allier PL, et al; Effect of rHDL on Atherosclerosis-Safety and Efficacy (ERASE) Investigators. Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297: 1675-1682.

- Jukema JW, Bruschke AV, van Boven AJ, et al. Effects of lipid lowering by pravastatin on progression and regression of coronary artery disease in symptomatic men with normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol levels. The Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS). Circulation. 1995;91: 2528-2540.

- Waters D, Higginson L, Gladstone P, et al. Effects of monotherapy with an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis as assessed by serial quantitative arteriography. The Canadian Coronary Atherosclerosis Intervention Trial. Circulation. 1994;89:959-968.

- Shaw JA, Bobik A, Murphy A, et al. Infusion of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein leads to acute changes in human atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res. 2008;103:1084-1091.

- Calkin AC, Drew BG, Ono A, et al. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein attenuates platelet function in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus by promoting cholesterol efflux. Circulation. 2009;120: 2095-2104.

- Waksman R, Torguson R, Kent KM, et al. A first-in-man, randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the safety and feasibility of autologous delipidated high-density lipoprotein plasma infusions in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2727-2735.

- Bailey D, Jahagirdar R, Gordon A, et al. RVX-208: a small molecule that increases apolipoprotein A-I and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in vitro and in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2580-2589.

- Sacks FM, Rudel LL, Conner A, et al. Selective delipidation of plasma HDL enhances reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:894-907.

- Nissen SE, Tardif JC, Nicholls SJ, et al; ILLUSTRATE Investigators. Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1304-1316.

- Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, et al; ILLUMINATE Investigators. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2109-2122.

- Stein EA, Roth EM, Rhyne JM, et al. Safety and tolerability of dalcetrapib (RO4607381/JTT-705): results from a 48-week trial. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:480-488.

- Cannon CP, Shah S, Dansky HM, et al; Determining the Efficacy and Tolerability Investigators. Safety of anacetrapib in patients with or at high risk for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2406-2415.

- Morgan JM, Capuzzi DM, Baksh RI, et al. Effects of extended-release niacin on lipoprotein subclass distribution. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:1432-1436.

- AIM-HIGH Investigators, Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T, et al. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

- HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. HPS2-THRIVE randomized placebo-controlled trial in 25,673 high-risk patients of ER niacin/laropiprant: trial design, pre-specified muscle and liver outcomes, and reasons for stopping study treatment. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1279-1291.

- Maccubbin D, Koren MJ, Davidson M, et al. Flushing profile of extended-release niacin/laropiprant versus gradually titrated niacin extended-release in patients with dyslipidemia with and without ischemic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:74-81.

- Lai E, Waters MG, Tata JR, et al. Effects of a niacin receptor partial agonist, MK-0354, on plasma free fatty acids, lipids, and cutaneous flushing in humans. J Clin Lipidol. 2008;2:375-383.

- Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Anantharamaiah GM, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2009;11:52-57.

- Navab M, Ananthramaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. The oxidation hypothesis of atherogenesis: the role of oxidized phospholipids and HDL. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:993-1007.

- Song X, Fischer P, Chen X, et al. An apoA-I mimetic peptide facilitates off-loading cholesterol from HDL to liver cells through scavenger receptor BI. Int J Biol Sci. 2009;5:637-646.

- Smythies LE, White CR, Maheshwari A, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic 4F alters the function of human monocyte-derived macrophages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C1538-C1548.

- Buga GM, Navab M, Imaizumi S, et al. L-4F alters hyperlipidemic (but not healthy) mouse plasma to reduce platelet aggregation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:283-289.

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Hama S, et al. Oral administration of an Apo A-I mimetic Peptide synthesized from D-amino acids dramatically reduces atherosclerosis in mice independent of plasma cholesterol. Circulation. 2002;105:290-292.

- Föger B, Chase M, Amar MJ, et al. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein corrects dysfunctional high density lipoproteins and reduces aortic atherosclerosis in lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36912-36920.

- Santamarina-Fojo S, Lambert G, Hoeg JM, Brewer HB Jr. Lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase: role in lipoprotein metabolism, reverse cholesterol transport and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11: 267-275.

- Calabresi L, Baldassarre D, Castelnuovo S, et al. Functional lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase is not required for efficient atheroprotection in humans. Circulation. 2009;120:628-635.

- Dullaart RP, Perton F, van der Klauw MM, et al; PREVEND Study Group. High plasma lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase activity does not predict low incidence of cardiovascular events: possible attenuation of cardioprotection associated with high HDL cholesterol. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208: 537-542.

- Alberti S, Steffensen KR, Gustafsson JA. Structural characterisation of the mouse nuclear oxysterol receptor genes LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Gene. 2000;243: 93-103.

- Naik SU, Wang X, Da Silva JS, et al. Pharmacological activation of liver X receptors promotes reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. Circulation. 2006;113:90-97.

- Peng D, Hiipakka RA, Xie JT, et al. A novel potent synthetic steroidal liver X receptor agonist lowers plasma cholesterol and triglycerides and reduces atherosclerosis in LDLR(-/-) mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1792- 1804.

- Cha JY, Repa JJ. The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis. The carbohydrate-response element- binding protein is a target gene of LXR. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:743-751.

- Braun A, Trigatti BL, Post MJ, et al. Loss of SR-BI expression leads to the early onset of occlusive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, spontaneous myocardial infarctions, severe cardiac dysfunction, and premature death in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:270-276.

- Masson D, Koseki M, Ishibashi M, et al. Increased HDL cholesterol and apoA-I in humans and mice treated with a novel SR-BI inhibitor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:2054-2060.

- Voros S, Joshi P, Qian Z, et al. Apoprotein B, smalldense LDL and impaired HDL remodeling is associated with larger plaque burden and more noncalcified plaque as assessed by coronary CT angiography and intravascular ultrasound with radiofrequency backscatter: results from the ATLANTA I study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000344.

- Okumura K, Tsukamoto H, Tsuboi H, et al; Samurai Study Investigators. High HDL cholesterol level after treatment with pitavastatin is an important factor for regression in carotid intima-media thickness [published online ahead of print January 24, 2014]. Heart Vessels. doi: 10.1007/s00380-013-0466-3.

- Pirro M, Vaudo G, Lupattelli G, et al. On-treatment Creactive protein and HDL cholesterol levels in patients at intermediate cardiovascular risk: impact on carotid intima-media thickness. Life Sci. 2013;93:338-343.