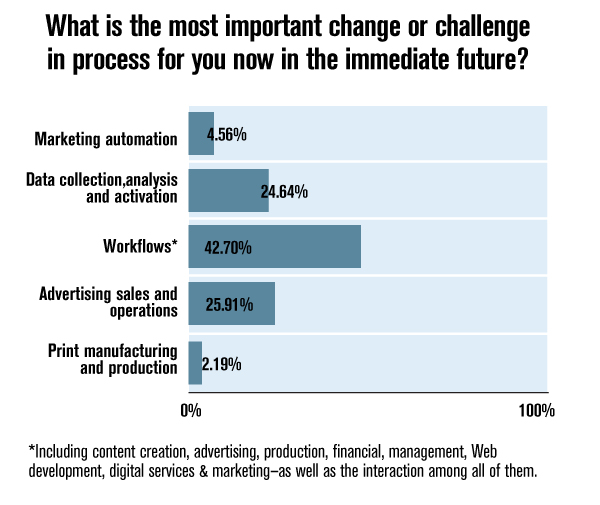

In June, FOLIO: conducted a brief email survey of its audience to determine what the biggest or most important process changes publishers are contending with. Of the more than 500 respondents, workflow management had by far the biggest response at almost 43 percent. Data collection and advertising were neck and neck with almost a quarter of the responses each. Marketing automation is barely a blip on the radar—so far. And print? Pretty much under control these days.

![]() he magazine media company of 2005 is gone. its processes, procedures and priorities would be nearly unrecognizable today. In fact, the media company that existed in 2010 is gone too. In a period of accelerated transformation, nothing is more striking than the scope—and pace—of change in the processes through which companies engage their customers. It’s not just peripheral or incremental change, either. What the industry is going through in 2015 is a revolution in processes. In advertising, content creation, marketing, back-office functions and everything in between, what was done just a few years ago has been rendered obsolete, as new ways to interact with and serve stakeholders push the old ways into the trash bin.

he magazine media company of 2005 is gone. its processes, procedures and priorities would be nearly unrecognizable today. In fact, the media company that existed in 2010 is gone too. In a period of accelerated transformation, nothing is more striking than the scope—and pace—of change in the processes through which companies engage their customers. It’s not just peripheral or incremental change, either. What the industry is going through in 2015 is a revolution in processes. In advertising, content creation, marketing, back-office functions and everything in between, what was done just a few years ago has been rendered obsolete, as new ways to interact with and serve stakeholders push the old ways into the trash bin.

“The model itself hasn’t changed,” says Doug Manoni, CEO of Source Media. “We produce content, and that creates engagement, and we monetize that engagement in various ways. What’s changed is that technology is transforming every single phase of the business. It’s ubiquitous. It’s impacting the business on a wholesale level.” [View a chart to see how Folio: readers graded their own biggest process changes.]

It’s a new world of “VUCA,” says Lenny Izzo, group president of legal media at ALM. “That’s an acronym for Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity. It’s an old military term that I learned as a tank driver.”

Uncertainty comes in the form of new competitors. It comes with the decline in traditional branding-based display advertising, and the rise of new formats like cost-per-lead sales and programmatic advertising. Complexity comes in the form of tying together new expensive technologies that cross email, web, billing, production, ad-management, and content creation. Ambiguity comes in the form of not having the expertise to evaluate expensive new systems, and sometimes not knowing the right KPIs. Volatility? How about not knowing whether a new software system that cost $1 million will be relevant in 18 months?

This report is an on-the-ground look at process change in magazine media companies and how it’s affecting, well, nearly everything, from organizational structure and staffing needs, to assumptions about efficiency and newly essential skillsets. We’ll look at overall philosophies and approaches, and then explore, mainly through case studies, what publishing companies and executives are actually doing.

Radical changes in process are driven by several things, of course. But mostly, it’s a function of two things: emerging technologies that enable new methods of serving markets, and a quest within companies for efficiency driven by economic necessity.

“To me, the change in publishing is similar to the change that airlines have had in the way they fill seats,” says Todd Krizelman, CEO of MediaRadar, which provides advertising intelligence services to magazine companies. “Ten years ago it was okay to have planes that were half full, and pricing was, you might say, very ‘flexible.’ In the subsequent wave of bankruptcies, there was enormous pressure to make sure that seats were filled and that every employee was doing something—and today airlines sell not just seats, but storage, food and beverages, preferred seats, and more.

“Media companies are similar,” Krizelman says. “They’re under enormous pressure to find new revenue opportunities, while maintaining the same or a better, higher class of service. It has meant a lot of forced change in processes.”

The emphasis there is on the word “forced.” Forced changes in processes become necessary because of inertia and territoriality. Change has to be required by executive-level leaders, and they’re often too late. “One characteristic of efficiency comes from the top of the organization, when you have someone who is fascinated with it,” says Mark McCormick, the CEO Gulfstream Media, a city and regional publisher in South Florida, and of Mirabel Technologies, which provides CRM solutions to magazine publishers. “Very rarely are senior executives people who get down into the nuances and processes of their companies. They usually try to hire it out and delegate it. And then they’re at the mercy of the people they hire.”

Companies where the culture is very territorial, McCormick notes, tend to be very inefficient—companies that won’t share metrics out of fear. The ones that are efficient tend to be the ones that share information across the company.

And while changes in process are extremely difficult, Krizelman suggests that it’s processes, not people, that impede success. He points to a famous case study of the NUMMI auto plant in Fremont, Calif., a joint venture between GM and Toyota that opened in 1982 and closed in 2009. “For managers, NUMMI is proof that most problems are solved by process, not by people. It proved that American workers could do the job as effectively as Japanese workers or any others, if manufacturing processes were fixed. So in media, when you’re looking to the future, it’s not about, ‘My older reps don’t want to learn, I can’t teach these people anything,’” Krizelman says.

Interestingly, for magazine publishers, there’s a significant paradox in process change. Because the business model is in a seemingly permanent state of flux, and because technologies become obsolete so quickly, media companies find themselves betting huge amounts of money on unproven ideas. “Maybe the paradox of process is that you’re forced to be hyper-efficient in the things you understand, to finance what you hope is our future,” Krizelman says.

Audience Marketing and Back-Office Processes

One company that’s pushing the envelope in efficiency and process change is ALM. The company realized that most of its major processes had to change in order to be more efficient at its core function, which is content generation and getting content into the hands of its audiences. One critical initiative was creating internal “Centers of Excellence,” Izzo says. Copy-editing is one of the centers. “We realized we would be more effective if we centralized copy editing across a very big national network,” Izzo says. “We have 15 offices. Our reporting structure was decentralized. So we created one center of operations.

“By doing that, we were able to raise standards across the board,” he adds. Centralizing the reporting structure allowed for the elevation of one common set of standards. It also enabled efficiency—a common workflow. “We were able to share work and divide bandwidth more appropriately,” Izzo says. “We had daily, weekly and monthly production cycles. Some of the people on the monthly frequencies were able to help with daily when they weren’t working on monthly magazines.”

And yes, it did create efficiencies. The copy editing function had about 15 people across the company, Izzo says, and subsequently, this particular Center of Excellence was able to cover its functions with less headcount.

Izzo says the copy-editing initiative, implemented two years ago, prompted a broader review of essential processes in a variety central-services areas. “We found that our functional areas had similar dynamics,” he says. “They were common across the business, but they were decentralized, with actual processes that varied from brand to brand and region to region. We ended up launching seven Centers of Excellence, all at the same time. They were for production, art, case digesting, research, book publishing and audience development, in addition to copy editing.”

The most dramatic change in process at ALM occurred in audience development. Traditional circulation headcount was reduced dramatically, from nine to three, with some of those positions repurposed to other areas, such as social media, database management, lead generation and marketing automation. “For us it’s building connectivity,” Izzo says. “We’re collecting a lot of data on our audience, and as they move through the metered paywall, we use the data to manage a highly complex audience marketing operation that does several things: Nurtures prospects toward subscriptions, by recommending stories, for example, and ultimately handing off highly qualified leads to a telemarketing operation.”

“The AD people have had to embrace new ways of doing their role,” he says. “Subscriptions and fulfillment are still vital. But the methods are so different from what they were three or five years ago that people have had to rethink how they do their jobs. And the new functions have become much more specialized. You can’t find someone who does the general role of AD and also all of those highly specialized roles.”

From the vendor perspective, all these changes in audience marketing have required major adaptation as well. One area that’s changed in the process of fulfillment is that it’s more SaaS-based, notes Aaron Oberman, COO of Omeda, a fulfillment provider. “Issue closes used to be a pretty arduous process, but we can do that now in just one click. All data is real time, so that makes that process a lot easier as well. There aren’t as many moving parts.”

Even more importantly, he notes, the focus is on the database. “The fulfillment aspect has become blocking and tackling,” he says. “Combining that with the marketing opportunities is where everyone needs to be today.”

One example of this approach was with Cygnus, Oberman says. When that company radically reorganized processes five years ago in advance of a divestment, Omeda helped align operations around industry verticals. “We aligned the data to match the verticals,” he says. “That made it more efficient for them, and easier.”

Dramatic Changes in Advertising

Audience profiling has deepened, dramatically, notes Source Media’s Manoni. But that’s hardly the only area within media companies that’s being radically changed. In the advertising arena, the game is moving rapidly toward lead creation. “We’re getting more and more into predictive analytics,” he says. ”The whole lead-gen model has evolved beyond what anyone anticipated even just a few years ago.” The lead-gen model (along with research) is the fastest-growing part of the Source Media business, he says, while branding-based advertising is the slowest.

Krizelman notes that inefficiency can be common in advertising processes. “I had one client who said they found all their advertisers in the telephone book,” he says. “They said they break even on that particular process. And when they changed their process, and had qualified leads, their sales tripled.”

This allowed the company to then invest back into process improvement, he says. How did they change their processes? They asked critical questions, Krizelman says. “Do advertisers buy with your competitors? Do they buy during this particular time of year? Do they buy integrated media? By doing this, companies can take an existing group of people—their sales teams—who don’t have to work any harder than they used to work, and drastically increase their sales.”

But in advertising, the biggest change over the last three or so years has been the emergence of programmatic buying. It has literally changed the game, and has required enormous adaptation on the part of media-company revenue producers, starting with the evolving perception of the format. What once was seen as a low-CPM channel for remnant sales is now a potentially lucrative reality—usually driven by marketers—that requires a steep learning regimen and major investments in buying, operations and analytics software platforms. “Video and native are hard, but they’re still very similar to the business everybody is in,” Krizelman says. “Programmatic is empowering, but also subversive, because if you’re not doing something, you may be unaware that your clients are leaving you for programmatic. In programmatic, though, you have lots of power. You set the price and the terms.”

Programmatic is already a completely dominant force in consumer-media advertising, Krizelman says, and it is coming to B2B media with remarkable velocity. The way to look at it, he adds, is as a delivery mechanism. “Do you want USPS or UPS?” he says. “Do you want your doctor in a hospital or in an outpatient clinic? I most associate it to the way stocks are now bought and sold.”

Digital media, says Gulfstream’s McCormick, is great at identifying what’s happening. “It can tell you what’s going on within your content,” he says. “There are all kinds of technologies that take us that down the road. What it is not good at is branding.” And yet, there are many advertisers in the city and regional sector that run branding campaigns. “This is why city and regionals are holding steady on their print,” he says. “But at some point you’ve got to be able to show behavior patterns. It’s a testimony to the tenacity of the sales efforts in city and regionals that they’re holding their own.”

Nevertheless, if you go down the programmatic path, you should be prepared to go all the way. Following the lure of programmatic, Here Media launched a private marketplace through PubMatic, a marketing automation software platform. The company quickly ran into trouble, however, when it realized how critical audience data is to programmatic. Here Media serves an LGBT audience and has historically been very protective of that data.

“We had private marketplace deals set up through PubMatic, but we don’t have a data management platform [DMP] so we set them up without layering data on top of them,” says group publisher Joe Landry. “We were not getting bid on because we didn’t have this layer of data.”

But given today’s media-buying environment, where audience data rules, the company is now wrestling with how it might be able to open up its data to the marketplace.

“In order to play in the private marketplace, or programmatic, period, you need to have a DMP,” adds Landry. “The world is changing, and I don’t want our concerns that may or may not be relevant today to stop us moving forward with the realities of keeping the business vital.”

Content-Creation Revolution

In content-creation, process change has been evolutionary, and it began a decade or more ago. But one thing’s true now: if your editors are print focused, or even text focused, they’re behind the times. And if they’re not fully conversant in content-management systems, social media and data-driven content, then they’re missing huge opportunities for engagement with their audiences, and monetizing that engagement.

Just how far are some companies taking their content? TEN: The Enthusiast Network, is taking it over-the-top. The company already has a major presence on YouTube through its Motor Trend channel, which now has about 3.2 million subscribers. But its April acquisition of Torque.TV will be folded into its upcoming OTT video platform Motor Trend On Demand.

But pivoting to more digital, which now accounts for 32 percent of the company’s revenue, and video content needed investment. The company cut 18 print titles out of its portfolio of enthusiast brands to reallocate resources. “We made some hard decisions and cuts,” says Scott Dickey, CEO of TEN. “We shut down 18 brands because we needed to get out in front of the process so we could reallocate funds to production and video.”

But for Dickey, it’s not only about video. The core print brands are still that; core. They’ll help drive a new affinity-based subscription model that Dickey hopes will pull more revenue across all of the platforms. “You can subscribe to the magazine, get a VIP experience at events, get access to proprietary products and get access to an exclusive channel all bundled through an affinity for a brand.”

At Rodale, president Scott Schulman has been bringing the brands closer together to drive efficiencies in content production. “Structurally, how do we knit the brands together,” he says. “We think we can make content offerings better and more extendable across the brands. Instead of doing things separately, we can do them together because we don’t repeat and overlap.”

An example of this is the recent hiring of a new head of food content, a senior editorial position that oversees content strategy across all the brands, which ultimately helps focus the company’s mission-driven healthy lifestyle market approach.

“The content is still tailored to the audience, but it gives us a collective strength that’s important to advertisers and consumers,” says Schulman. “An area like food touches everything we do, but we don’t have a bunch of food brands, per say.”

“Back at Gulfstream Media, we say, ‘Let’s try to make our content database driven,’” McCormick says. “We do surveys and we extend the use of the content from those surveys. Say we do a 30-question survey. Fifty people respond. We build stories around the surveys, and we can reuse relevant parts over many months.”

Driving that, he says, is the search for how to compete with the new content giants—information companies like Facebook and Google that are pushing out content much faster than publishing companies. “The platform companies are getting an incredible amount of money from advertising,” McCormick says. “We all say content is king, but you could make a very strong argument that platform is king. The companies that don’t have to create content—they either scrape it or steal it or you post it voluntarily—they are the ones getting the lion’s share of revenue.”

Data Management and Marketing Activation

Most industry practitioners agree that the areas most affected by process change are data management, analysis and activation, most directly centered around marketing. Indeed, across the magazine industry software companies are starting to sell innovative programs that identify unknown visitors, match them against various behavioral patterns and even serve ads and promos, in real time.

“One of the most significant changes in media-company processes is digital lead-identification tools,” McCormick says. “We think this is a huge market potentially.

“You have to have the ability to identify leads for customers that other people can’t. Right now lead identification is largely driven by email, we are going to be able to move beyond email and identify leads based on other algorithms.”

But data has had a profound impact in the B2B market, where publishers are re-engineering their operations around it and making it central to their asset portfolio. And there are few companies that have moved faster in this direction than Randall-Reilly. In the last ten years, the company has shifted its revenue mix to 70 percent digital and data—21 percent is print.

The key driver? Data and digital are measurable and you can measure return in near real time, says president and CEO Brent Reilly. And like most companies that have moved decisively and quickly, it’s all about following the money. “We cannibalized our print faster than necessary because we were moving to what was of value to the client,” says Reilly. “Are the clients more satisfied today then they were yesterday? Are they spending more with us now? If so, it doesn’t matter where that occurs.”

Although the magic moment was the ability to marry audience engagement metrics and other first-party data that media companies have historically been experts at collecting with equipment purchase history and other market data.

“When you start putting that all together and have real intelligence and marry that with behavioral data, you start to uncover not just the right person, but the right time,” says Reilly.

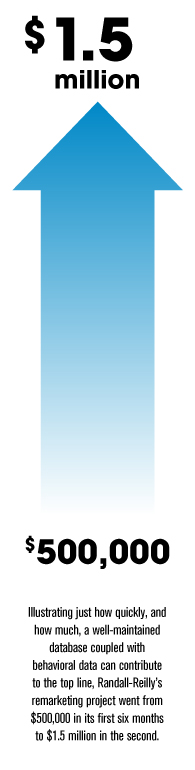

With a focus on scaling data and managing it tightly, Randall-Reilly launched a very productive remarketing operation. “It made $500,000 in the first six months and $1.5 million in the second,” says vice president of audience development Prescott Shibles, who was hired last year and launched the remarketing campaign.

The technology and data interplay happening under the hood is incredibly complex and makes the old model of slapping content onto a website to draw traffic that hopefully clicks on a banner seem positively quaint.

“Not too long ago, our websites were basic online representations of our print magazines,” says Rob Paciorek, senior vice president and chief information officer at Access Intelligence (Folio:’s parent company). “We monetized those sites largely though banner ads that we hoped readers would like enough to click on in order to visit an advertiser’s website.”

The primary focus in those days, Paciorek says, was getting content online. What was learned about the audience after that was secondary. Now, the content and data imperatives are hand-in-hand.

“We’re using new tools like the customer data platform Lytics to identify our readers’ behaviors, and we use that information to understand what content is resonating so that we can provide a better experience for them,” he adds. “We’re then taking the data from Lytics and flowing it into Optimizely, a landing page optimization tool, and Lyris, an email service provider, so we can create multi-channel marketing efforts that are crafted for each reader.”

But of course, publishers shouldn’t keep all that customer knowledge and segmentation ability to themselves. That kind of targeting and marketing power can be just as lucrative for marketing partners.

“Of course all of that data also helps us to identify where our readers are in their purchase journey, which allows us to deliver highly qualified leads to our advertisers,” says Paciorek. “Everything is so much more complex these days, so it not only takes new tools to make it all happen, it also takes a new skill set. Everyone has to think digitally, but our audience has to be at the center of everything we do. We’ve changed processes, but we’ve also changed our internal structure to better align ourselves around our audience.”

The upside on developing these programs for adverstisers goes way beyond the banner.

“We’ve secured two large deals this year that greatly eclipse any large banner ad sale we’ve ever made—probably by as much as 3-6 times,” says Paciorek. “Those deals aren’t for every advertiser we work with, but it takes us out of the commodity game and focuses the discussion so that it’s back to the value of our audience.

“The difference is, it’s going to take a team of people to fulfill these deals, as opposed to a single trafficker who can place Web banner ads,” Paciorek says. “This again brings in the complexity factors I mentioned earlier. Aside from the implementation challenges, some of the more digitally savvy marketers we work with are demanding ROI that goes way beyond click-through rates, so we need to use an analyst to build a proposal that includes detailed metrics on what we estimate they will be getting in return for their spend.”

Conclusion: Establishing KPIs for a New Era

All of these things mean that executive managers need to rethink how they’re tracking performance, and more important, what they’re tracking. Says Krizelman: “There’s a lot less slack in the system. You have to go through a lot of material to know how you’re performing.”

Source Media’s Manoni says he’s reengineering everything around all-new technologies and business models. “All of our internal dashboards are changing. I’d love to get my hands on the very best dashboard in the industry.”

Source Media’s KPIs include tracking digital revenue, revenue by product mix, audience metrics, Web metrics, CPMs, cost-per-lead revenue, revenue by FTE and lots more. “But the dashboard has changed,” Manoni says. “It’s being developed. Now you have to look at all kinds of things every single month.”

“We try to marry strategies like this with two things,” adds Reilly, “very trackable execution with visible metrics so everybody knows what we’re doing, and the spirit of always trying to get better.” ![]()