In a time when lending is tight, alternatives abound

By Michelle Graff

In a time when lending is tight, alternatives abound

By Michelle Graff

In a time when lending is tight, alternatives abound

By Michelle Graff

Harriet Greenberg, Friedman LLP

Tom McDermott, Borro

Michael Melfi, general counsel for Funderbuilt

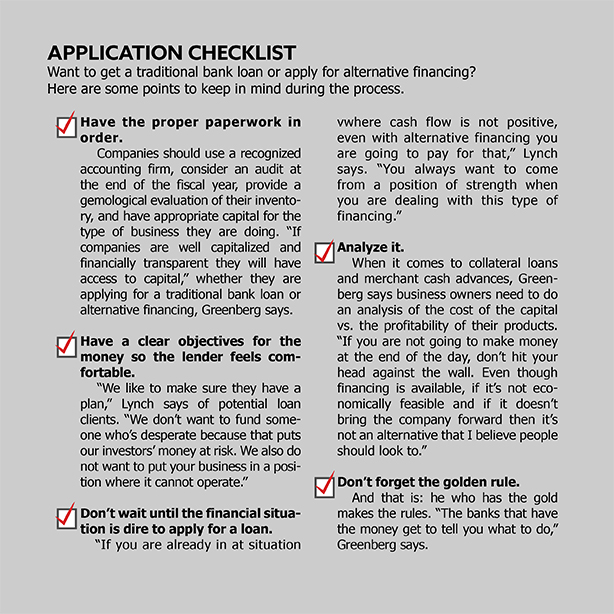

Application checklist

Want to get a traditional bank loan or apply for alternative financing? Here are some points to keep in mind during the process.

- Have the proper paperwork in order. Companies should use a recognized accounting firm, consider an audit at the end of the fiscal year, provide a gemological evaluation of their inventory, and have appropriate capital for the type of business they are doing. “If companies are well capitalized and financially transparent they will have access to capital,” whether they are applying for a traditional bank loan or alternative financing, Greenberg says.

- Have a clear objectives for the money so the lender feels comfortable. “We like to make sure they have a plan,” Lynch says of potential loan clients. “We don’t want to fund someone who’s desperate because that puts our clients’ money at risk.”

- Don’t wait until the financial situation is dire to apply for a loan. “If you are already in a situation where cash flow is not positive, even with alternative financing you are going to pay for that,” Lynch says. “You always want to come from a position of strength when you are dealing with this type of financing.”

- Analyze it. When it comes to collateral loans and merchant cash advances, Greenberg says business owners need to do an analysis of the cost of the capital vs. the profitability of their products. “If you are not going to make money at the end of the day, don’t hit your head against the wall. Even though financing is available if it’s not economically feasible and if it doesn’t bring the company forward then it’s not an alternative that I believe people should look to.”

- Don’t forget the golden rule. And that is: he who has the gold makes the rules. “The banks that have the money get to tell you what to do,” Greenberg says.

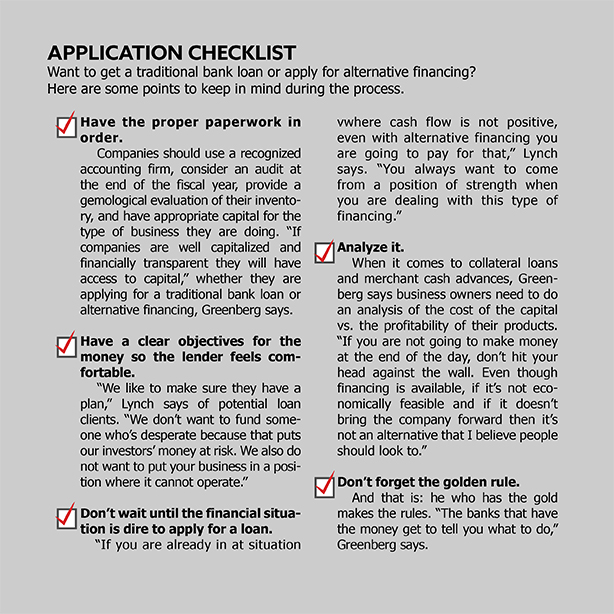

Application checklist

Want to get a traditional bank loan or apply for alternative financing? Here are some points to keep in mind during the process.

- Have the proper paperwork in order. Companies should use a recognized accounting firm, consider an audit at the end of the fiscal year, provide a gemological evaluation of their inventory, and have appropriate capital for the type of business they are doing. “If companies are well capitalized and financially transparent they will have access to capital,” whether they are applying for a traditional bank loan or alternative financing, Greenberg says.

- Have a clear objectives for the money so the lender feels comfortable. “We like to make sure they have a plan,” Lynch says of potential loan clients. “We don’t want to fund someone who’s desperate because that puts our clients’ money at risk.”

- Don’t wait until the financial situation is dire to apply for a loan. “If you are already in a situation where cash flow is not positive, even with alternative financing you are going to pay for that,” Lynch says. “You always want to come from a position of strength when you are dealing with this type of financing.”

- Analyze it. When it comes to collateral loans and merchant cash advances, Greenberg says business owners need to do an analysis of the cost of the capital vs. the profitability of their products. “If you are not going to make money at the end of the day, don’t hit your head against the wall. Even though financing is available if it’s not economically feasible and if it doesn’t bring the company forward then it’s not an alternative that I believe people should look to.”

- Don’t forget the golden rule. And that is: he who has the gold makes the rules. “The banks that have the money get to tell you what to do,” Greenberg says.

When it comes to the jewelry industry and banking, 2013 did not end on a high note.

In December 2013, KBC announced plans to sell Antwerp Diamond Bank to Shanghai-based Yinren Group, while Bank Leumi followed with an announcement in January that it would close out its diamond jewelry financing portfolio by the end of 2014. As the year wore on, the news only grew worse. KBC said in September that Yinren failed to submit to the National Bank of Belgium the “comprehensive file” necessary to complete the sale and it would be forced to shut down ADB in the coming months, unless a savior surfaces during the wind-down process. The exit of banks from the industry, and the tightness of credit in general, is impacting players of all sizes along the supply pipeline, and the crunch hasn’t gone unnoticed. As of this writing, De Beers was set to hold a briefing with banks in New York in an attempt to reach out to the financial community, a first for the 126-year-old diamond miner and marketer. Harriet Greenberg, a partner in charge of the apparel, fashion and jewelry group at New York accounting and consulting agency Friedman LLP, says the reasons so many banks are exiting the jewelry industry are the lack of transparency and the perceived financial risk. Many companies in the industry haven’t had audits, don’t have sophisticated financial records and/or haven’t gotten a gemologist to evaluate their inventory, all of which larger banks require when they loan.

“Banks don’t have a feeling of lending to them because, traditionally, there hasn’t been a whole lot of financial transparency,” Greenberg says. “This is something that goes right across the distribution chain.”

Also adding to banks’ unease are eroding margins and continuing consolidation.

Think: the financial collapses of once-big players such as Friedman’s (more than 400 stores; filed Chapter 11 in 2008), Whitehall Jewelers (more than 300 stores; filed Chapter 11 in 2008), Finlay Fine Jewelry (more than 700 locations; filed Chapter 11 in 2009) and Ultra Stores (nearly 200 units; eventually bought by and absorbed into Signet Jewelers Ltd.). The culmination of industry consolidation occurred earlier this year when Signet bought rival Zale Corp., merging the country’s two largest mall jewelers to create a mega-chain of some 3,600 stores. “These are all things that make traditional lenders uncomfortable with the industry,” Greenberg says.

Quick(er) cash

The jewelry industry’s manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers are not the only businesses finding it difficult to secure traditional bank loans in the post-recession era. Business owners in all types of industries, particularly those heading smaller firms, find themselves searching for alternative sources of financing.

The “trailblazer,” so to speak, among these alternative forms of financing was the merchant cash advance, says John Lynch, marketing director for Express Business Loans in Amityville, N.Y. Express offers fixed-term, fixed-payment loans to small businesses with interest rates starting around 11 percent as well as merchant cash advances.

A merchant cash advance works like this: the lender analyzes the borrower’s credit card sales for a specific period of time and advances them a certain amount of money based on their credit card sales volume. The lender then works with the credit card processor, taking a cut every time the borrower batches out their credit card sales until the funding is repaid. Merchant cash advances do not have an interest rate. They have a factor rate, the percentage of the advance amount the provider charges. Lynch says the cost of capital in a merchant cash advance can range from 1.15 to 1.35, depending on the funding amount and projected payback.

“For jewelers, we would lean more toward our loan program,” he notes. “It may be a little bit more difficult to get approved for but the pricing’s cheaper.”

There’s also collateral lending, which has a new player on the scene in New York: London-based Borro. Operating in the U.K. since 2008, Borro opened its New York office about 2 1/2 years ago. Tom McDermott, general manager of the company’s U.S. business, said Borro works by taking physical possession of a retailer’s inventory and then lending against its value, typically around 70 percent. For example, if a retailer turned $1 million in inventory over to Borro, the company would float them a loan for $700,000. If the loan isn’t repaid, then Borro, which staffs on-site gemologists who evaluate the inventory, takes permanent possession of the inventory. The interest rate on these loans is 2 to 4 percent per month.

The biggest hurdle a business owner might have to overcome in taking out this type of loan is physically relinquishing possession of their inventory; McDermott notes that jewelers might feel that they’d rather have their bracelets, earrings and necklaces on hand at the store in case a customer wants to buy them. Still, he says, Borro will return the inventory if the retailer has a buyer and has paid off the loan.

The company also has a program where they will find a sales channel for merchandise: the retailer typically receives 70 percent of the inventory’s value up front and receives the money from the sale that remains after the principal, interest and costs associated with the loan are paid. McDermott acknowledges that Borro’s services are more of a short-term solution with a higher interest rate.

Traditional bank loans are a better option for the long run, but only for those who are able to secure them. “All the big banks are backing out of this industry, especially the diamond industry,” he says. “That’s why we are getting calls from people looking for alternative forms of financing.”

Lynch says the merchant cash advance was the first type of alternative financing product to experience growth. It grew to become a multi-billion dollar industry over the last decade but has plateaued in popularity as other alternatives have emerged, alternatives that serve as middle ground between merchant cash advances and collateral loans and the traditional bank loan.

A now-crowded field

Among these is the growing practice of crowdfunding, raising money for a project or business via a large group of people generally reached through the Internet.

Crowdfunding started to gain steam around 2008 or 2009, in lockstep with social media, which makes it possible to easily share with huge networks of people. Today, the most well-known crowdfunding portal is Kickstarter. Pennsylvania-based jewelry designer Anthony Lent used Kickstarter earlier this year to develop and promote a new silver line and was able to exceed his goal of $50,000 thanks to the 345 people who “backed” the project.

In return, he rewarded his backers a silver pendant (for a$125 donation or more), Anthony Lent-branded chocolates and shout-outs on social media site Twitter. The jewelry company said its success is an indicator of the viability of crowdfunding portals for jewelry designers looking to raise capital.

However, Michael Melfi, an attorney and author of The Simple Secrets of Crowdfunding, points out that simply asking for donations isn’t the only option with crowdfunding. Melfi heads a boutique law firm based in Birmingham, Mich. and is the general counsel for another crowdfunding portal, Funderbuilt.

He says Funderbuilt provides donation (where people just give money to a cause-based campaign), reward and equity-based projects. For the equity-based crowdfunding ventures, the person gives a piece of equity in their company in exchange for an up-front investment.

Melfi says those seeking crowdfunding support need to have all of the necessary financial documentation, just as a company would if they were going into a bank seeking a traditional loan, and also need to seek legal advice; there are federal and state laws that govern this type of funding. Theyalso need to take it one step further. Because they are going to be asking a wide range of people—not just friends, family or the loan officer at a bank—for funds, they need to tell the story of why they need the money in a creative way that can be shared online. It is no different than the way jewelers train their sales associates to sell the romance associated with diamonds and not just run down the four Cs. A successful crowdfunding campaign goes beyond profit and loss sheets, Melfi says.

It “has a good story, a good video. It’s important to have begun to create … an online community with which you can share your story and the project,” he says. “Create an audience you can communicate with.”

In addition to Funderbuilt, other crowdfunding portals with an equity-based option include AngelList and CircleUp, all of which are solid options, Melfi says. He says individuals and businesses have raised hundreds of thousands, even millions, of dollars through crowdfunding, which wasn’t possible before the rise of social media. He sees it as part of a larger paradigm shift to the cloud, meaning the Internet, and the crowd, a reference to the many people one can connect with through channels such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. “That’s the benefit of social media,” Melfi says. “That’s the benefit of being online.” This shift to the “cloud and the crowd” is, in some cases, replacing old ways of doing business that no longer work, or perhaps no longer even exist, in the post-recession era. ![]()